My Irish-preaching was very successful at first, but greatly opposed afterwards

In 1863, Rev Henry MacManus, the first Irish Missionary of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, published Sketches of the Irish Highlands.[1] He discoursed on the development of spreading the gospel in the Irish tongue in pre-famine Ireland:

Preaching in Irish was new, not having been tried by any of our ministers; so I was wisely permitted to make the attempt unfettered by any regulations as to place or time. Two courses were open to me. One was to itinerate, and the other was to concentrate my labours in a given locality. Both I have tried, the latter having been carried out, not in Connemara, but in Kerry.[2]

‘Presbyterianism,’ he wrote, ‘has been hitherto confined chiefly to one province.’ Improved roads and development of transport however, had brought about change:

Old people in Kerry remember when it required six whole days to travel from Kerry to Dublin and when the adventurous travellers, before starting, usually ‘made their wills’ and were then escorted to the coach-office by weeping friends. Even when I first visited Kerry, I reached my destination only in the evening of the third day. Now, by rail, it is the journey of hours instead of days.[3]

Rev MacManus opened the Kerry mission in 1842.[4] He described his field of labour thus:

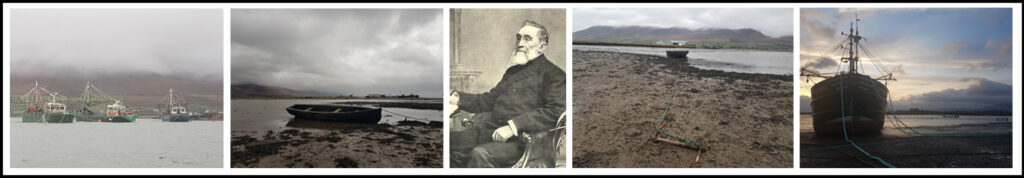

It is a wide valley at the head of the Dingle bay, stretching from Sliav Mish, south of Tralee, to the Iveragh mountains, west of Killarney, and embracing the villages of Castlemaine, Milltown and Killorglin.[5]

So much is known about Rev MacManus’s Presbyterian Home Mission in Kerry. However, one year later, during Christmas week 1843, Rev Batt O’Connor, parish priest of Milltown, addressed an open letter to the Right Rev Dr Denvir, Belfast, on the subject of the Kerry Home Mission.[6] Rev O’Connor had read the annual report of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland to which Rev MacManus, domiciled in Milltown, had greatly contributed.[7]

Rev O’Connor was far from impressed, and felt it his duty to ‘undeceive the honest Presbyterians of Belfast’ on the content of this report in respect of the Presbyterian stations in Milltown and Killorglin. ‘Mr McManus states that his congregation in Milltown averages fifty or sixty, sometimes seventy, or eighty,’ wrote Rev O’Connor, ‘but he does not tell his friends in Belfast what the creed of his congregation in Milltown is – or what it was – and as he does not, I will’:

His audience in this town, which averaged from thirty or forty, including men, women and children (save and except the Scotchmen who are working at Muckross and who come here only on great days) are to a man Protestants … and these very persons who are at his preaching in the morning, without I believe, a single exception, are found in the Episcopalian church at 12 o’clock; nay, more, if you ask any of them whether he is a Presbyterian, he will answer in the negative.

‘Neither has he told the honest men of Belfast this,’ fumed Rev O’Connor:

I, H McManus, am living in Milltown for nearly two years and though I get £100 a year for myself, £62 14s 8d for my diet, &c £32 13s for my teacher, and something for Scripture Readers – still I have not got one Roman Catholic to join my ranks.

Rev O’Connor went on to state that Milltown and its union (Listry) contained a Catholic population of over eight thousand, ‘I dare Mr McManus to name one Roman Catholic who has joined his ranks from this locality though his exertions … no, he could not name one, and still, he has the impudence to state in this report that Scartaglin and Cahirciveen would be desirable places to have a station!’

Such stations in Kerry would be ‘prosperous to him and his gang in getting money,’ continued Rev O’Connor, ‘but as far as getting converts from Catholicity, a greater falsehood was never uttered, as is evident from his complete failure in this town, which, he says, he found garrisoned by two priests, a nunnery, and a monk house.’

‘Not only that,’ added Rev O’Connor, ‘he says that we priests have sounded the tocsin of war against him’:

If he means that we have cautioned our people against giving ear to him or his followers, he is right, but if he means to insinuate that we urged the people to offer any violence to him or his followers, he states what is false, the contrary is the fact, as we have advised the people to offer him no violence … he distributed his tracts that he canvassed by the roadside and in the fields and all this to the great annoyance of the inhabitants, who are almost Roman Catholics to a man. Is it, then, to be wondered at that he has been hooted? If a Roman Catholic had the impudence to act in this manner amongst the Presbyterians of the North, how would they feel?

Rev O’Connor turned his attention to the Mission Station in Cromane:

Rev MacManus says that in consequence of his being several times attacked, and his being threatened with the loss of his life, he has been obliged to travel to Cromane by sea. How can he reconcile this statement with the fact that on last Sunday he did travel from Cromane on Her Majesty’s high road through a Catholic population without a policeman, without any escort, save a lady and the driver of her car? If Terence lived, he could have said Solus cum sola and though he can pass without fear to and from any part of this country to Milltown he has had the audacity to recommend the Directory to purchase a pleasure boat in order to approach Cromane.

‘For what?’ asked Rev O’Connor, ‘not to convert the Catholics, for they would not listen to him, but to convert Mr Uriah Sealy, a Protestant and brogue-maker who is anxious to succeed Mr Hugh Gordon as Scripture Reader, the said Hugh Gordon being dismissed in consequence of his having brought ruin on a female, a Scripture Reader or hearer of his, in the north of Ireland, who followed him with a child to Killorglin a few weeks since – what a crew to convert the Roman Catholics of Kerry!’[8]

Commenting on other parts of the report, Rev O’Connor went full throttle on local scandal:

The two widows, Rev MacManus does not give their names, but I will. The first is a woman of the name of Ray, the illegitimate daughter of a Mr Ray of Keel, she lived with a pensioner of the name of Lowe, a Protestant; whether she was married to Lowe or not is a question; after Lowe’s death the Rev D O’Connor PP spoke of her in one of his chapels not for being a Presbyterian for she was not one, but for living in a state of sin with a Palatine of the name of McClure.[9]

‘The other widow to whom Mr McManus alludes,’ continued the reverend, ‘is not a widow though he may think so; her name is Savage; her husband is alive in America, he sent for her some time ago but before the letter arrived she had a child by a Palatine of the name of Neil in this parish, her husband’s friends knew this so they wrote to him to say that whatever acquisition she may be to Mr MacManus, she could be none to him.’

‘Disreputable as they were,’ quipped Rev O’Connor, ‘they left him.’

Rev O’Connor did not ease up, but moved on to ‘the next great gun, James Charley, son of Daniel Charley, a convert to Catholicity’:

Pat married his own cousin german, N Neil, against his father’s will; she was a Protestant; this took place about 16 years ago, and from that time until this day, James Charley was not known to comply with any of the duties with which Catholics comply. I was coadjutor for five years in the parish of Killorglin and during that time James Charley’s father repeatedly spoke to me about his son, whom he represented to be so stupid that he could not learn the Lord’s Prayer but, all of a sudden, he is enlightened.

‘Rev MacManus describes Mr Charley as an intelligent man and his conduct greatly satisfying’ said Rev O’Connor, ‘he must be easily satisfied.’

As the fire of his pen waned, Rev O’Connor did not withhold a final jibe:

Rev MacManus stated that James Charley, not being able to live at Cromane, in consequence of the hostility of the Catholics, had to fly. I pledge my solemn word to the honest Presbyterians of the North of Ireland that a greater falsehood was never uttered … He has four children, the eldest I believe was baptized by the Parson, but I will not split hairs.

Rev Henry MacManus was hardly impressed. ‘Sir,’ he wrote to the editor of the newspaper, ‘it was not until the night of Thursday 27th ult that I could procure a copy of your paper which contains a very violent and abusive attack made on me by the Rev B O’Connor of this town [Milltown], the professed object to contradict and falsify a report of my labours during the year ending June 1843 which I, in fulfilment of my duty as missionary, made at the last annual meeting of our church, or as it is called, the General Assembly; and which met in Belfast in the beginning of July last.[10] Mr O’Connor, by garbling a few sentences, would make it appear that the report is written in an offensive and vain-glorious spirit, the reverse is the fact.’

To illustrate, Rev MacManus quoted a passage in the report about the priesthood, ‘notwithstanding all their hostility to me’:

In private life they are often hospitable and generous and not infrequently courteous and polished in their manners … amongst [the laity] I am happy to number among my friends several respectable Roman Catholics but I must not mention their names for though gratitude would induce me to do so yet prudence forbids it.

Rev MacManus proceeded to dissect and contradict Rev O’Connor’s letter point by point, countering the accusations, describing them as ‘sound and fury signifying nothing … mere beating the air and thrashing the water.’ He offered a reward of 5s sterling for any accusation ‘shown to be real, direct and well grounded.’ He wrote:

Mr O’Connor denies that any violence was ever afforded me. What, for example, do you say, Mr O’Connor, to the attack made on me and others who accompanied me in Cromane on December 3 1842? Was there no violence offered that day? Must the public take your unsupported assertion in preference to the testimony of Mr Edward Twiss, Mr Uriah Sealy, William Blennerhassett, ___ Huggard of Killorglin, &c, all of whom were present on the occasion and will, I doubt not, confirm their testimony upon oath.[11]

Rev MacManus described the parish priest’s letter as out of context because the report covered a year’s missionary work and Rev O’Connor’s letter alluded to ‘less than three lines in the report.’

Rev MacManus used the opportunity to give an abstract of the report in which a number of his achievements were noted. It was shown that there were two mission stations, one in Milltown and another in Killorglin, on his settling in the district, and that he opened three stations at Laheran, Cromane and Leac, built a schoolhouse in Laheran educating forty-five students, and established two Sunday Schools, one in Milltown and one in Laheran.[12]

So ended the clash between priest and Presbyterian, at least as far as the press was concerned.[13] The Mission Station in Kerry was subsequently broken up, as revealed in Sketches:

A few years ago, when the funds of our Church ran low, this mission was broken up – a sad necessity. But God did not withdraw His blessing with the removal of that instrumentality. This will appear from the following letter which I have received while writing these pages from William Lunham Esq, a worthy merchant of Tralee. He there describes a revival that has taken place in that very locality.[14]

Reverend Bartholomew O’Connor

Reverend Bartholomew O’Connor (1798-1890) was born on the 15th August 1798 at Gortnaminsha (Gurtnaminch), Listowel, County Kerry, son of Bartholomew (Parthnan an Seanoir) O’ Connor and Catherine Horgan (Harraghan). He was educated at Killarney and Maynooth and ordained in Killarney in 1825 by Most Rev Dr Sugrue, Bishop of Kerry. He was first appointed curate of Firies and later of Tuogh where he built a church. He was subsequently promoted to parish priest of Kilgarvan ‘for the special purpose of combating souperism.’ During his ministry there he erected a church and made a successful four-year tour of America in aid of Killarney Cathedral, collecting £4,000 (and another £1,000 in the diocese on his return). In October 1841, soon after his return from America, he was appointed priest of Milltown parish which he served for over forty years until failing health caused him to retire circa 1887. He died on 4 October 1890 and was buried in Milltown. A short sketch of his life and labours was published in the Kerry Sentinel, 8 October 1890 (p2) in which he was credited with the existence of the Presentation Convent in Milltown. Rev O’Connor, a strong friend of the Liberator, was described as a good priest, a true friend, and a sterling patriot.

Reverend Henry MacManus

Reverend Henry MacManus was born in Virginia, Co Cavan, c1819. He was ordained on 10 February 1841 as the General Assembly’s first Irish-speaking missionary to Catholics in the west of Ireland having spent six months in Connemara learning the local dialect. He went to Kerry in 1842 until poor health caused him to withdraw from his preaching stations in Kerry in 1846. He worked in Athlone the following year, and in 1853 was installed as minister of the congregation in Mountmellick. He resigned in 1858 through ill health (Ref: Dictionary of Irish Biography) and died at Pembroke-avenue, Sandymount, Dublin on 16 October 1864 aged 45. He was buried in the parish of Clontarf, the service conducted by Rev H Magee. Rev Magee, in Fifty Years in ‘The Irish Mission’ (p206) remarked that Rev Henry MacManus’s letters appeared in The Missionary Herald under the signature ‘A Milesian.’ During his residence in Milltown, Rev MacManus married, in December 1844 in Dublin, Margaret, eldest daughter of Thomas Ashley Esq of Glenpool Place, Co Dublin. The minister had children but no more is known of his family (DIB).[15]

___________________________ [1] The preface to Sketches reveals that it came about following a request from Rev Hamilton Magee (1834-1902) for contributions to the periodical Plain Words, of which he was editor (and, posthumously, author of Fifty Years in ‘The Irish Mission’ (1902).) Soon after the publication of Sketches, it was reported that a copy had been burned by a Roman Catholic barrister, ‘the barrister exhibited very bad taste in destroying such an excellent book, and as the burning of the martyrs in past times furthered the cause of truth, so may the burning of the Sketches but rapidly increase its circulation’ (Banner of Ulster, 24 September 1864). [2] Sketches of the Irish Highlands, p103. He added, ‘[Kerry] does not fall within the province of this volume, though it will be glanced at towards the close.’ Rev MacManus hoped that his Sketches would be well received and if so, enable him to produce Sketches of the Southern Highlands. However, he died soon after publication of Sketches of the Irish Highlands. Rev MacManus concluded this book with a seven-stanza poem entitled The Kerry Hills, which reveals a very special attachment to the county. [3] Sketches of the Irish Highlands, p97. [4] Sketches of the Irish Highlands, p102. Rev MacManus paid tribute to the ‘late Dr Dill, who, while pastor at Cork, was always a warm friend to missionaries in the south, and who himself, after the famine, laboured for some years efficiently in the Kerry mission that I had opened in 1842.’ The Tuam Herald (29 January 1853) carries a letter from Edward G Browne in relation to Dr Dill in Kerry. This may relate to Dr Edward Marcus Dill (1813-62) who was installed in Cork in 1838. He took charge of mission stations in Kerry and elsewhere in the south of Ireland and with his wife, Sarah Jane Robinson, established several industrial schools in Kerry (Dictionary of Irish Biography). [5] Sketches of the Irish Highlands, pp232-233. [6] Letter to the Editor of the Cork Examiner, 20 December 1843. Cornelius Denvir (1791-1866) Roman Catholic Bishop of Down and Connor. Further reference, Dictionary of Irish Biography. [7] Report of the Home and Foreign Missions of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland (3rd Annual Report, 1843). [8] Rev McManus subsequently responded: ‘My late Scripture Reader, tho’ the woman who charged him with the sin was of extremely doubtful character, she having admitted on oath that she had brought the very same charge against another person and that wrongfully, and though I have in my possession a letter written in the names of those in the North to whom she referred as witnesses in her favour, which denies the truth of her statements, that he was dismissed, notwithstanding. What more could have been done, had he been proved guilty by the most indubitable evidence?’ [9] Rev O’Connor added, ‘Mr McManus hearing of her grievance espoused her cause with all the spirit of a knight errant; he took her up, but finding that she was likely to bless his ‘interesting flock’ as he styles his congregation with a young McClure, she was shipped off to Dingle where she has added to the motley crew of the Gayer, Moriarty and Co’s congregation.’ [10] Response written from Milltown, 3 January 1844, published in the columns of the Tralee Chronicle, 6 January 1844, and a copy to the Irish Examiner, 10 January 1844. [11] ‘I may inform the public that a very serious attack was threatened me the last time that I was in Cromane … my safety was owing solely to the circumstance that Mr Edward Twiss, a person very much respected by the people, happened to be along with me at the time.’ There is a quaint tale about Cromane which dates to the pre-famine period. A man from Killarney bought a pig at Milltown May fair for £1 and buyer and seller parted. The pig was put into a yard for safe keeping while the buyer moved on to purchase a cow. However, when he came to pay for it, he discovered he had paid the pig seller a five pound note instead of a one pound note. He looked for the seller in vain; he had gone from the fair with no clue to his whereabouts. The man from the Lakes, however, liberated the pig in the hope it would ‘face home.’ He followed the bouviveen with the ardour of a fox chase for nine long miles to Cromane, where, as he had hoped, the pig walked into its former abode with a grunt. The man was at once handed back the £5 note by the Cromane seller, he having up to that point not realised the error. [12] The Presbytery of Cork visited 'Laherin, about ten miles from Tralee’ the principal station in Mr M’Manus’s interesting field where, ‘in the school-house lately erected by our Mission Directors in that place, we found assembled to meet us a congregation of between seventy and eighty. Of these, about twenty-five were converts from Popery, forty Roman Catholic inquirers after the truth, and the remainder persons who had always been Protestants’ (Sketches of the Irish Highlands, pp232-233). [13] The Kerry Examiner, which published Rev O’Connor’s letter (issue 2 January 1844) chose not to publish the response of Rev MacManus, ‘such productions are familiar to us – they generally abound in quibbles and scriptural quotations’ (issue 12 January). They did however publish an additional letter from Rev O’Connor in which he challenged the Synod of Ulster to put him and Rev MacManus ‘face-to-face.’ [14] Sketches of the Irish Highlands, pp238-239. ‘I am happy to inform you that the work of the Lord is going on prosperously. Last night I was at the weekly prayer-meeting at Castlemaine … there could not be less than sixty in attendance. It continued for two hours and a half, even then, they were not willing to separate. In another letter Mr Lunham laments the giving up of the mission school-house which I had got erected there twenty years ago.’ A note on merchant William Lunham is contained in Recollections of the Presbyterian Church Tralee (2021) by Russell McMorran. The McMorran Papers form part of the archive of Castleisland District Heritage, courtesy Chris and Clare McMorran. See ‘An Overview of the McMorran Collection.’ [15] Thomas Ashley Esq (died at Glenpool 28 July 1868) of Glenpool House, Roundtown, Terenure, Co Dublin and his wife, Isabella Heiton (died at Glenpool on 20 June 1884), sister of Thomas Heiton (1804-1877) of Scotland and of Melrose, 4 Leinster Road, Rathmines, Dublin, had another three known daughters. In 1844, Frances Ashley (died at Glenpool on 4 April 1884) was married in Rathfarnham Church to Thomas Peile Esq of Dublin. On 30 August 1848, in Rathfarnham Church, Eliza Ashley was married to Rev Roland S Morewood, Antrim. Lily Ashley died on 2 November 1883 at St John’s Hospital in ‘Beyroot.’ It is worth noting that J H M’Manus, MD, Ballymahon, Co Longford is acknowledged in Sketches of the Irish Highlands. James Henry M’Manus MD died at his residence, New Street, Longford, on 23 March 1881 aged 84 years.