Big Boys Don’t Cry, a book by Ted O’Shea of Muckross, Co Kerry, has just been added to the archive of Castleisland District Heritage.[1] The work provides information on O’Shea genealogy with interesting links to the Ahern family of Castleisland.

It traces how the author’s great grandfather, James O’Shea, went as a teenager to Ohio where he found work on the railways.[2] James was unusual in that he returned to Ireland during the famine and settled in the Killarney district. As the author observes, ‘It is obvious that my great grandfather knew there was land wanting there.’ He leased a farm in the townlands of Gortahoonig and Ardagh which had been occupied earlier by the Mayburys.[3]

As James was not displacing anyone, he had no compunction but to lease the vacant house and lands, setting up his small tenant dynasty on the spot.[4]

James O’Shea married Mary Leary from Cloonydonigan, Ballyhar in 1845. A large family was born to them between 1850 and 1872 including James, born in 1857, who met Mary Ahern from Lough Na Gore, Callaghan’s Cross, Castleisland during a spell in Chicago.[5] They married in 1884 and had a large family including fourth child, Bernard Joseph O’Shea, born in 1897, father of Ted O’Shea.[6]

Bernard Joseph O’Shea studied agriculture at Darrara Agricultural School, Clonakilty, Co Cork. When his older brother Timothy signed up for the army in 1921, Bernard was called home from his studies to take up the running of the farm.

Bernard married May Lyne of Coolies in 1932 and together they continued the farming tradition at Gortahoonig, Muckross. At the same time, they converted their family home into a guesthouse. They had nine children; Ted was third youngest, born in 1941.[7]

Ted O’Shea attended Lough Guittane National School in 1945 and St Brendan’s College Killarney in 1952. He later studied agriculture at university where he graduated with a degree in agricultural studies. In 1966, he gained employment in Caherciveen with Kerry Committee of Agriculture as an Agricultural Adviser and in 1969, worked in Bantry for Cork Committee of Agriculture. He returned to work in Kerry – in the same capacity – in 1972. He retired early in 1997 from a job that, as his memoir shows, had also changed with the times.

The author recalls growing up in Killarney under his father’s guiding principles of never use a weapon, never kick a man when he’s down, never hit a woman. He recounts occasions such as visits to the circus, snaring rabbits, and serving mass as an altar boy in Derrycunnihy Church. He also recalls delivering potatoes to the orphanages in Killarney.

An outing in 1959 by ‘Ghost train’ to an All Ireland match at Croke Park raises a smile. Jarvey Paddy Whitty O’Sullivan ‘found a weakness’ in a door of the stadium – ‘a thousand or so people followed him into Croke Park for free.’[8]

The darker side of twentieth century life is also uncovered, such as the corporal punishment dispensed by staff of St Brendan’s College. ‘The devil is in you!’ the students were told, and the devil would be ‘beaten out of them’:

This was the argument for corporal punishment … should you be bold, act out, be late (even if no fault of your own) or be unfortunate enough not to have the right answer to a question, you were beaten with a cane.[9]

The darkness is offset however by the writer’s approach to the oppression of the times. He refused to bow to authority he regarded as unjust; indeed, as he puts it himself, ‘I enjoyed contradicting authority.’

And always some soft silver ray Athwart the gloom would burst To chase the heavy clouds away, When things were at their worst – from The Birds Will Sing Again by Rev Hartigan[10]

At the age of four, the author suffered what today might be described as an abomination. A growth on the side of his neck was removed surgically without sedation and he was told not to cry, ‘Big boys don’t cry’:

How can a four-year-old not cry when grown men might have easily fainted being put under the knife like that? What level of disease warranted the horror of that operation? I experienced a form of attack at the age of four for reasons I did not understand.[11]

The stricken child suppressed his physical response to the pain, as instructed, but could not do the same with his emotions. The outcome was anger, ‘A type of anger a child should not have to feel.’[12]

This, the author came to understand, led to problems with alcohol addiction and depression.[13] Meetings with AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) helped him to recover and, as he puts it, allowed him to drive ‘without fear of the breathalyser test.’[14] He sought help for depression from the organisation AWARE Defeating Depression, founded in 1985 by Dr Patrick McKeon of St Patrick’s Hospital, Dublin.

Despite his struggles, and they were considerable, the author sought to support organisations that had helped him.[15] He assisted in getting meetings of AWARE started in Killarney, the first held in the Dromhall Hotel. Indeed, his book includes information on different organisations in place such as KNPI and the Rural Transport Programme to assist those seeking help.[16]

Ted O’Shea married Cecilia in 1970, and considers himself ‘blessed to have a great wife.’ He also counts the blessings of friends made along his journey through life, including the late Liam Lynch of Knocknagoshel, author of A Stranger to Darkness (2006) to whom he made a promise to write a memoir:

Part of the reason for my writing is my experience of being a driver for a deceased blind friend, Liam Lynch RIP … Towards the end of his life, he told me, ‘Ted, we had fourteen great years.’

Another friend, Kieran Crowe (1961-2005), who trained him as an advocate of mental health services and helped to establish Citizens Information Services throughout Kerry, is also acknowledged with great admiration. As the author puts it, Kieran ‘did more in his short life for mental illness than anyone I know.’[17]

Big Boys Don’t Cry runs to 61 pages. Short it may be, but pithy and honest, and a valuable contribution to the history of twentieth century Irish society, not least the progress of psychiatric treatment and medical practice, but also in agricultural and social change, locally and nationally.[18]

___________________________

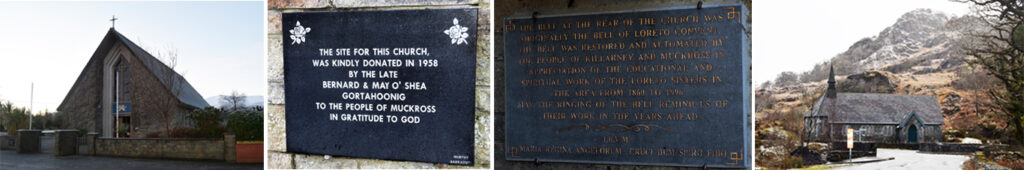

[1] Big Boys Don’t Cry “An intimate portrait of life and mental health” published in 2018. The production of the book was assisted by Sean Quinlan PC, Rattoo Heritage Society, Ballyduff, Tralee, Co Kerry. [2] This James was the son of Patrick O’Shea (born Killarney 1785) and Ellen O’Connor (born Killarney 1794); at the time of the marriage of Patrick and Ellen in Killorglin in 1818, Patrick’s address was Arlahus (Ardlaghas, parish Knockane) equidistant between Beaufort and Killorglin. Patrick was the son of James O’Shea of Killarney and Julia Moriarty. [3] ‘Home Farm’ was a vacant property occupied earlier by the Maybury family who had been responsible for the reforestation of the Herbert estates at Muckross ‘believed to be the descendants of a William Maybury of Cleady north of Kenmare.’ The original home farm contained seventy acres in total. ‘The site outside farm in a different townland one and a half miles from home farm is where I currently reside. As many as twenty-five acres has been continuously farmed over the years.’ [4] P10. ‘Today the main property at home farm has 70 acres except with the eventual donation of one and a half acres of land for the building of the new Muckross Church in the early 1960s.’ ‘A new church is to be erected at Muckross in the heart of Killarney’s scenic beauty ... A committee was selected to push the project with Mr Bernard O’Shea as Chairman and Messrs Denis Horan, N.T., Loughquittane and Maurice Moriarty of Muckross as hon. Secretaries. A site to be willingly donated is to be selected at a spot most convenient to all. The new church will be a chapel of ease supplied with priests from Killarney. The church will serve about 500 people from Muckross, Gortagullane, Killeagy, Coolies, Faugh and Gortdromakerrie ... Those who help to build this Church of God will not alone pay a tribute to the martyrs for the Faith who in the dark hours found shelter at Muckross but will provide an edifice in the heart of Ireland’s most beautiful scenery and enable the men and women from the mountains of Mangerton and Torc, from the picturesque village of Muckross, from the farm lands of Faugh and Coolies, to have once again the Sacrifice of the Mass celebrated in their midst’ (Kerryman, 19 March 1955). ‘New £14,000 Church Blessed and Dedicated ... Now about half ways between the Abbey of Muckross and the old Friary at Faughbawn stands this new church at Gortagullane, on a plot donated by Mr Bernard O’Shea ... The Church was dedicated by the Bishop to the patronage of The Holy Ghost. In this it is unique, as it is the only Church in the diocese of Kerry dedicated to the Holy Spirit’ (Kerryman, 22 July 1961). [5] P11. Loughnagore, otherwise Loughinagore, lies in the parish of Killeentierna. [6] An account of Bernard Joseph O’Shea’s experiences in Killarney during the Civil War period is given on pp12-13. Family members in Gortahoonig are recorded in the Census of Ireland 1901 and 1911. [7] Ted’s birth name is Timothy. [8] P27. [9] P25. On this subject, see ‘Stinking Soup and Sausages: Life in a Kerry Seminary in the 1960s’ on www.odonohoearchive.com. [10] Around the Boree Log and Other Verses (1921) by John O’Brien otherwise Rev Patrick Joseph Hartigan (1878-1952) parish priest of Narrandera, whose parents were native of Lissycasey, Co Clare. A biography of Rev Hartigan, John O’Brien and the Boree Log, by his nephew, Fr Frank Mecham, was published in 1981. Ted O’Shea remarked on the literature of Rev Hartigan, which he enjoyed during a trip to Sydney, in conversation with Janet Murphy on 24 January. [11] Pp18, 19 & 21. [12] P26. [13] Ted O’Shea started drinking in 1961, and was advised to seek help for alcoholism in 1978. He was diagnosed with manic depression as an outcome of that consultation. [14] P55. [15] The author describes how he planned to take his own life (p35) and also the different drug therapies he underwent. [16] Pp39-40. As the author says himself, his book was written ‘in order to help others’ (p49). [17] Pp36, 41 & 42. [18] The author has a very small number of copies left. Please contact odonohoearchive@gmail.com in this regard.