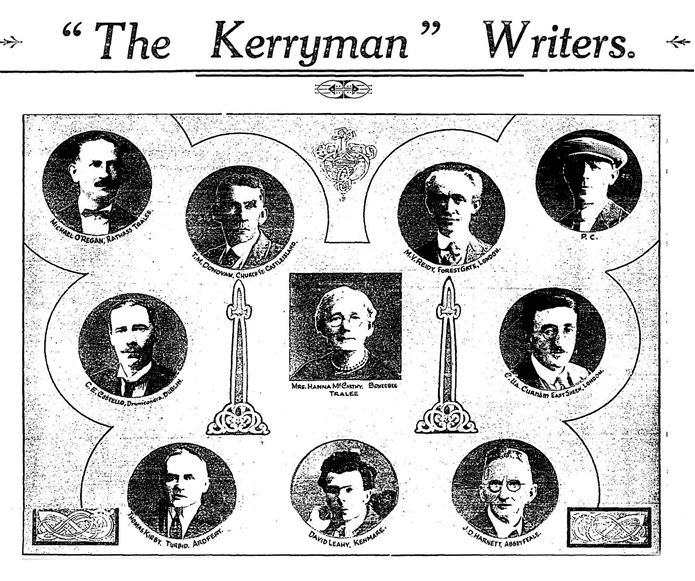

In January 1934, The Kerryman issued a ‘pictorial almanac,’ described as an introduction to some of their special correspondents who helped to make the newspaper ‘so widely popular.’[1] It was printed on art paper at the Kerryman printing works in The Market and Russell Street, Tralee:

These contributors are already well-known by repute to The Kerryman readers. Mrs Hannah McCarthy and ‘P C’ are still remembered for the wordy war they waged in verse in our papers. T M Donovan and M V Reidy are both natives of Castleisland, and their writings are eagerly read by a wide variety of admirers. Mr Reidy, whose first appearance in print was in the United Irishman, under the editorship of the late Mr Arthur Griffith, contributed to nearly fifty periodicals in Ireland, Great Britain and the USA and has also written several books. Mr Donovan has three books to his credit. C E Costello and E Ua Curnáin are responsible for ‘Marketing Notes and Forecasts’ and ‘Social Credit Notes’ respectively, two features of absorbing interest. The writings of Michael O’Regan, Thomas Kirby and J D Harnett put these three in the first rank of Kerryman contributors. David Leahy, of Kenmare, as well as being a valued contributor of poetry and prose, is also an artist, whose drawings have appeared from time to time in The Kerryman.[2]

Almost ninety years on, a survey of the above writers reveals a gap in the knowledge of their work, and the rarity of their publications. A good is example is T M Donovan’s A Popular History of East Kerry, a highly praised work by a man regarded as Castleisland’s most important social historian of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[3] Donovan died in 1950 and his headstone in St Stephen’s churchyard, Castleisland, does not bear his name. Castleisland District Heritage is trying to raise funds to rectify this.[4]

Less known is M V Reidy, in full, Maurice Vincent Reidy, born in Castleisland on 23 August 1874, eldest of the large family of Castleisland shop-keeper, David J Reidy and Mary Morris.[5] At the age of about sixteen or seventeen, he went to New York but returned to Ireland in about 1899. For a period he edited the Killarney Echo, some of his work appearing at this time under the pen-name ‘Slieve Mish.’

In 1903, he was living in Killarney when he published a book of verse entitled From Kerry Hills, much of its content written during his school days in Castleisland.[6] The following is an illustration of his prose at this time extracted from his account of Castleisland Castle. Here he imagines the last moments of Gerald, Earl of Desmond:

Truly there are episodes in our chequered history that we would willingly forget and one of them is the manner in which the last of the great Desmond Earls met his end. In imagination we can picture him seated near the fire in a peasant’s cot, his noble head sunk heavily on his breast, his hair hanging in the Irish fashion over his shoulders, his face thin and haggard from privation and care, his body gaunt and fleshless, his powerful arm before which many a sturdy British warrior bit the dust, his eyes bloodshot from want of sleep, but still flashing at times with a light that showed the indomitable soul within. The door of the cot is opened, and half a dozen troopers rush in. The foremost – Daniel Kelly – raised his sword and nearly cut off one of the Earl’s hands at a blow … The loss of blood from the wound in the Earl’s arm caused him to grow weaker, and Kelly, thinking it would be too much of a burden to bring a dead body back to the camp, told the Earl of prepare for death. Lifting his sword he struck the Geraldine’s head off, and the headless trunk of the last of the Earls rolled over on the sward. The head was sent to England as a present to Queen Elizabeth and was stuck on a spike for the populace to gape at until the flesh shrivelled away, the hair fell off, and all that was left of an Irish rebel was a grinning skull. Not far from the ruin is the little churchyard where the body reposes, and the spot where he was so foully murdered can still be pointed out. His memory lingers yet around the place, as a little winding road leading through the wood is known as Boher-na-Earla to the present day. As the autumn wind blows through the leaves above, it brings a sound as of a gentle wail to the listener’s ear, as if some spirit lingered eternally over the spot to mourn in shame and anguish the dark deed by which the great Munster chieftain met his end. And around the Kerry firesides old men on winter’s nights still breathe a curse on the recreant Celt whose hand struck down the noble Geraldine, as they tell the tale of the ancient glories of Desmond.[7]

On 16 September 1905, Maurice Vincent Murphy married Annie Elizabeth, the Headmistress of Manor Park and Central Park Girls’ School, East Ham and only daughter of Charles Furby, 25 Field Road, Forest Gate, London in the Church of St Antony of Padua, Khedive Road, Upton, London.[8] After his marriage he went to live in Dublin and in 1908, he was offering a typewriting service to writers who wished to contribute to newspapers and periodicals, as he was himself doing.[9] He later moved to London where he was a member of the Gaelic League. In 1926, his historical novel, The Vision Beyond, was received to wide acclaim.[10]

In Forest Gate, he began a connection with the Franciscan Order, and became a tertiary soon after his elder son, Fr Gabriel OFM, entered the 1st Order in 1934.[11] Shortly before the Second World War, he moved to Blackheath near Guildford in the parish attached to the Friary of the Holy Ghost, Chilworth, where he lived in active retirement.

He died on 19 July 1951 and as Apostolic Syndic of the Friary, was given the honour of burial in the Friary cemetery. Maurice Vincent Reidy was survived by his widow, and sons Fr Gabriel OFM and Robert Reidy, his daughter in law, and two daughters.[12]

Notes on Other Contributors

Michael O’Regan

Michael O’Regan contributed poetry and short opinion pieces to the Kerryman during the 1930s. In one article, he spoke about the receptivity of the mind in early years when certain events leave indelible marks that ‘time seems utterly powerless to eradicate’:

The young mind between the ages of four and twelve, it seems to me, takes mental snapshots of a few outstanding events, and they remain engraved on it for all time. They hang on the walls of it, so to speak, for ever. They dominate the memory when everything else looks blurred and indistinct.[13]

The author described such an experience from his own childhood which happened when he was about twelve years old. His neighbours, ‘quiet, inoffensive, semi-literate people,’ had a beautiful two-year-old son, ‘a pocket edition of Adonis’ who got his looks from his mother, ‘who was as handsome as Venus de Milo or a Missilina’:

The locality was indescribably poor and we were all as poor as the proverbial church mouse but the parents of this extraordinarily handsome child were absolutely poverty stricken. Those were callous days for the working class, their plight was appalling. There was no dole, no old age pension, and even when they had work their wages were only to ward off starvation. Then when idleness came on they actually starved. I knew families who were often three days fasting.

One evening, the author was passing his neighbour’s door, which was always open, and saw the child laid out – he had died from measles. He went in and only the mother was inside, rocking herself to and fro:

I stood silently at the meagre fire. The stillness of the grave enveloped the shabby naked kitchen. The lovely boy was laid on a table. Two or three little cheap candles glimmered near him. The mother sat on an old sugawn-bottomed chair at his feet … all the agonies of humanity were depicted on her mournful face. She looked as if she had reached the very pinnacle of irreparable misfortune … These are the sights that make the Anarchist and the outlaw.

The author looked upon the face of the child:

Great artists have scoured the world looking for beauty to transmit it to canvas. Gorgeous landscapes, dazzling sunsets, famous men and infamous women, pastoral scenes, and rustic beauty in every shape and form but to my mind all these things are commonplace and mediocre when compared with the face of a child … the masterpiece of the Creation and an unerring symbol of our immortality.

Michael O’Regan paid tribute to the unnamed infant in ‘The Face of a Child,’ a ten-stanza verse from which the following is taken:

Its workmanship heightens the glory of God, It transcends over planets and spheres; The rest of creation looks puny and odd When its angel-like beauty appears. ’Tis fairer to see than the face of the morning, When flowers are unfolding to welcome the day; It holds pride of place in the world’s adorning, A heavenly light to illumine the way.[14]

Patrick O’Connor – ‘P C’

Unlike some writers for Kerry newspapers like ‘Specs’ (Brosnan of Castleisland) and ‘Kerry Rover’ (O’Neill of Brosna) who wrote under pen-names, ‘P C’ (Patrick O’Connor) wrote under his initials.

A contributor to The Schools’ Collection revealed how ‘P C’ was a noted horse trainer who rode after the hounds in Kildare and trained horses in Kerry for Mr Hewson:

All the poems Patrick O’ Connor wrote were in English. One of the poems he made was “The Bobbed Haired Lassies” which held in the paper for several weeks. The reason he made this poem because he did not like the idea of girls bobbing their hair. A Mrs McCarthy from Killarney and himself had a long argument in poetry, she backing the girls and he opposed to it … Patrick O’ Connor was a very intelligent man. Everybody was anxious every Friday to get the “Kerryman” to see the poems for and against the bobbed hair.[15]

The ‘Bobbed Hair’ controversy, given below, brought Pat O’Connor to public attention. One writer recalled how he met ‘P C’ in the townland of Ennismore, Listowel in 1928 and the two became firm friends:

It was not alone ‘bobbed’ hair and the other prevailing fashions of the period which ‘P C’ commented on with brilliant pen. His eulogistic tribute to the performance of a Listowel greyhound after winning the Irish Cup at Clounanna was in itself an excellent example of his masterly rhyming skill … In dealing with literary opponents ‘P C’ could be satirical in a friendly and charming way. Those of us who remember the ‘bobbed’ hair controversy in the pages of The Kerryman remember that in his replies, the verses were invariably interspersed with humour and witticisms, a technique which he knew would bring about the desired results. Many an aspiring opponent shrank into silence under the power of his facile pen. He was one of a band of able and brilliant contributors who subscribed to the pages of The Kerryman at that time. Throughout the long years after he had left Ennismore, he never failed to write to me and often, in some of his letters, he would hint in a veiled way how his contributions and those of his contemporary correspondents had helped on rocketing The Kerryman towards the pinnacle of popularity it enjoys today … The time came when ‘P C’ had to say farewell to Kerry but he never forgot Ennismore when the fields were green, the friends he left there and the newspaper which had done so much to make his name a household word in Kerry.[16]

Pat O’Connor hailed from Tipperary.[17] In 1963, a full length photograph of him appeared in the Kilkenny People in which it was revealed that he had lived in that county and contributed poetry to the newspaper for many years.[18] His verse on sporting, athletic and general topics had won him wide acclaim and gained him the title, ‘The Bard of the Nore.’

He retired to Kells, Co Meath where his passing was recorded in the Kerryman in February 1964.[19]

Hannah McCarthy

A battle of the sexes began when Pat O’Connor (‘P C’) penned a six-verse poem about a bobbed hairstyle in fashion with women at the time:

I feel depressed and sad tonight – my heart is filled with woe Since I met my darling Biddy where we parted years ago, I remember, when we parted, how the sun came shimmering down On her fair and handsome features and her lovely locks of brown. When I met her I was horrified: I could not understand What made her look so ugly now who once was sweet and grand. I gazed in silent wonder; yes, I looked and looked again – Ah! My heart near bust asunder when I found she bobbed her mane.[20]

The poem triggered a storm, some readers retorting in verse others responding in prose.[21] As one aggrieved correspondent put it, ‘If, as Mr P O’C says, the fish have left the river Feale, that’s got nothing to do with our hair.’[22]

A person at a hurling match in Lixnaw found the style ‘disgraceful’:

My attention was arrested at intervals by the bobbed hair lassies. Not one girl, old or young, could say in Lixnaw on Sunday last that she has not yet bobbed her haid. Disgraceful is the conduct of those beautiful comely lassies when they turn their attention to their hair, but at a later day they will rue their folly.[23]

Mrs Hannah McCarthy of Caherciveen and Tralee, however, proved an able opponent, meeting the antagonist head-on, stanza by stanza, in the same suit of armour.

You men are always taunting us, you harp upon our clothes; You taunt us on our nice bobbed hair, and on our silken hose. Yet well we know you love us, and what I say is true: Without the silly woman I don’t know what you would do. Who’d mend your socks, and brush your clothes, and who would fix your tie? And when you’re blue and out of sorts who’d raise your spirits high? Who’d find your little soothing pipe, that often goes a-hide, If that poor silly woman was not always by your side?[24]

Pat O’Connor complimented Mrs McCarthy on her poetic style, and spoke of his high regard for her, before commenting on her status:

And so you’re wed? Ah, dear, how sad! Alas! Too late to fret! Oh, had I roamed by Moyderwell before your spouse you met. Your features rare and figure fair I’m sure I couldn’t miss; But as my lips are beardless, well, I dare not mention kiss. My kind regards I send you now, and won’t you write again? Your lines I’ll gladly welcome, ma’am – they’ll soothe my puzzled brain, For as the shades of faded days roll down life’s steep incline, My thoughts go drifting sadly out along the fields of Time.[25]

A fond farewell appeared soon after:

With much regret I’ve read that verse in which you’ve said farewell – Though small the word it bears such weight that makes my big heart swell, Your lines I always loved to read, of them I’d never tire – Your sporting spirit, madam, too, I could not but admire. The bobbed hair girls will miss you, as a Councillor and a friend, For not a lawyer in Kerry, ma’am, could them like you defend. And I am sorry, madam, you’re retiring from the fight, Because you’re of that rare old stock that’s always out of sight.[26]

One year on, Mrs Hannah McCarthy found herself in another wordy war with Mr O’Connor on another subject, fashion. Pat O’Connor wrote:

A thousand welcomes, madam! Sure ’tis proud I am indeed To see you shine in battle line – I’m glad you took the lead. You came to help the gentle sex to criticise the men; I know you’re game to have a fight, so here I am again. I wondered where on earth you went, you’re silent now so long; We missed you in the Kerryman, where once you went so strong. So now you’re on the warpath, and you can lash away, But be prepared, and don’t be scared – I’ve columns got to say.[27]

Mrs McCarthy responded to the call:

A thousand thanks kind sir, for all the welcome you extend, And also for the compliments which you so kindly send; You say you missed me; yes you did, my pen I put away, But when the women are attacked, sure I must have my say. But rest assured my gallant sir, I never will be scared, We met before a year ago, so I am well prepared. The bobbed hair was the trouble then, ’tis now the price of clothes And what will be your future fad, ’tis goodness only knows.[28]

Mrs McCarthy suggested her antagonist should take a wife:

Take my advice that’s all you want to keep you nice and straight, And keep your money tidy and on you she’ll always wait, A clever nice young lady, a neat and tidy wife, Who’ll hold the needle ready to sew buttons all her life. You haven’t an idea my friend how happy you will be, When you’ll sit and chat with wifie and the baby on your knee. For tho’ you are a modern man, you’ve kindness in your eye, So go and tell your neighbour Joe you are not marriage shy.[29]

In response, Pat O’Connor explained ‘Why the Men are Marriage Shy’:

Again I hail you, madam, as a champion with the pen, And I admire you for your pluck in tackling me again. I love a fearless fighter, and in you there is no to back, But you throw your flashes brighter out across the troubled track. You still defend the women, and believe that I am wrong; And, of course, like every woman, to your trade does it belong To try and have the last word, and swear that you are right, But in me there’s no surrender, so then on must go the fight.

And why being single was the way to go:

You talk about pullovers and his shirt of crepe-de-chene, Fancy socks and brilliantine – such things he’s never seen. His shirt is made of flour-bags, ma’am, and dare he give a grunt – With a photograph of Latchford’s mill across the back and front. His socks, poor man, they’re odd ones – one is brown, the other grey – He’s never had a pair to match since wifie came his way. While she’s rambling through his pockets, if he moves to gets a smack, He’s in mourning for his single days, and wishing they were back.[30]

We are never likely to see anything like the Bobbed Hair and Fashions controversy again,’ wrote Pat O’Connor in 1925, ‘it was so universal, and then we could lash away without offending anyone or without being in any way personal; and if it had to be left between the ladies and myself, particularly my old friend, Mrs Hannah McCarthy, who is an extremely witty woman and one of the most honourable opponents I’ve ever had the good fortune to knock up against.’[31]

Five years on, Pat O’Connor penned another verse entitled ‘Farewell’ dedicated to the many writers who had continued to take up the pen in battle with him:

All pens are dropped, a truce is called and peace at last proclaimed, The blaze of war has fizzled out, though long and high it flamed. Still fresh and good I stand and watch the smouldering ashes fade, Though many a bombshell round me burst as to and fro I swayed. But looking back through glasses fair along the battle trail, I see no scars or broken bones, I hear no sigh or wail. And as the wheel of time goes round and pleasant memories fly, Dear friends, again, I grasp my pen to bid you all good-bye.[32]

However, he had a few special lines for his old opponent, Mrs Hannah McCarthy:

But where must Hannah McCarthy be? – I hope she’s overground, I missed the volleys from her pen as each week came the rounds, Faith, she can fight, ah! Yes, and write – she’s champion of her day, I hope the belt from my old friend will never pass away.

Johnnie Roche, Chairman of Castleisland District Heritage, recalls how his parents would often talk about this literary episode and the enjoyment it gave to readers at the time. His understanding was that Hannah McCarthy was fictitious, an invention of Pat O’Connor himself. The image of Hannah may also therefore be a disguise. If anyone can help setting the record straight, please contact Castleisland District Heritage.

Charles E Costello

Charles Edward (or Edmond, both names given in death notices) Costello of 7 Millmount Terrace, Drumcondra, Dublin died on 22 May 1951. The following obituary outlines his achievements:

For over twenty years Mr C E Costello had contributed a weekly article on agricultural and economic subjects to The Herald until ill health forced him to discontinue writing a few months ago. Mr Costello was a native of Edmondstown, Ballaghaderreen, being younger son of the late Patrick and Mrs Brigid Costello. He completed his education at the Albert College of Science, Dublin. On qualifying as a creamery manager, his first appointment was at Ramelton, Co Donegal, and later at Kilnaleck, Co Cavan. For many years he was manager of the Ballyhaise Agricultural Creamery and Co-Operative Stores. When he retired from creamery management, Mr Costello returned to his first love, journalism; he had been a reporter on the Sligo Champion in his youth. He wrote extensively on agricultural topics and was a regular contributor to several provincial papers. The small farmers had in him a great champion, and in all his writings he showed a deep insight into the problems of the agricultural community. He was a great opponent of the centralisation policy, and never ceased to advocate the improvement of rural life. The deceased was also a keen student of political affairs and as a young man had taken part in the Sinn Fein and other national movements. He was a personal friend of many of the political leaders of the past half-century and though he had not taken active interest in politics for some years past, was always a staunch supporter of the national movements, cultural as well as political. Mr Costello is survived by his widow, Mrs S Costello; a son, Mr Charles E Costello BE and two daughters, Mrs B Penston and Mrs M Blake. After Requiem Mass at Corpus Christi Church, Whitehall, Dublin, the funeral took place to the family burial ground at Kilcolman, Ballaghaderreen.[33]

E Ua Curnáin

Earnain Ua Curnáin hailed from Loughill and wrote for the Kerryman from the 1930s. He retired to Doon, Ballybunion and died there in 1981. The following announcement gives some details of his life:

The death during the week of Earnain Ua Curnáin severed another link with The Kerryman. Earnain lived a long and full life. Indeed, he reached the ripe old age of 92 last January. His links with The Kerryman go back to the thirties, when his able pen advocated the use of social credit as the nation’s monetary system. He kept up the campaign for thirty years and, indeed in our own time, he still plugged away looking for monetary reform, pointing to the state of Alberta in Canada as an example of how successful it could be. Earnain, who lived in Doon, Ballybunion, was a native of Loughill. He worked with the British Admiralty in London and in his youth in that city shared digs with Michael Collins, who also was in the British Civil Service at that time. He retired from the Admiralty in 1947 and came to live in Ballybunion 23 years ago on his marriage to Josephine Harty, a native of the resort. He was buried in Ballybunion on Tuesday. May he rest in peace.[34]

Thomas Kirby

Thomas Kirby – Tomás Ua Ciarrbhaic – contributed the Ardfert Notes to the Kerryman under the pen-name ‘The Trapper’ in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He also published poetry, his poem, ‘An Appreciation of Sean Casey’ appearing in 1926.[35]

In 1932, he published, in collaboration with Michael O’Riordan BA, ‘Twixt Skellig and Scattery, a booklet ‘immersed in the very riches of the wonders of old Ciarraighe’:

The authors have delved in mines of virgin treasure and explored the remote wilds beloved of the Muses. This is but the first of a series of volumes which must be of enthralling interest to the people of Kerry.[36]

Michael O’Regan of Rathass praised the work of the men in verse:

Do not wait until they’re dead to find out that they’re great, Don’t reserve your meed of praise until it is too late; But give it now, while still they live, because it is their due, And then you’ll never have to grieve for things you failed to do. Their work will live, and future men will choose it for their guide, And though they’re now obscure, their pen will stir the wells of pride.[37]

In August 1933, Kirby’s ‘Fire-Raisers or The Rhyme of the Insurance Man’ appeared in the Kerry Reporter[38] and in December another, ‘Bold Billy Brady, the Bard of New Biz: The Song of the Irish Insurance Agent.’[39]

Following the publication of the calendar in 1934, the record on Thomas Kirby falls silent.[40] If anyone can add further detail, we would be delighted to hear from you.

David Leahy

David Leahy resided at 7 Rock Street, Kenmare, and contributed articles and poetry to The Kerryman in the 1920s and 1930s. Musings of a Kerryman: Kerry of my Dreams, a book of prose and poetry, appeared in 1950.[41]

David Leahy, ‘late of Munster Arcade, Cork,’ died at his residence in Kenmare on 26 February 1952 and was laid to rest in Old Kenmare cemetery. He composed the following lines just weeks before he passed:

The Invalid’s Room Oh, how I wish to see again the simple joys of old, A field of waving buttercups or shining marigold. Or hear the joyous blackbird sing, and watch the speckled trout, Leaping across the waterfall, where bubbles float about. How different from my present state, closed in a silent room, Where precious little comes to break the weariness and gloom. Here do I spend the passing hours from dawn to break of day, Trying to keep the spirits up and drive dull care away. And yet I must not think that all my sufferings are in vain, That God has not His own reward for those who suffer pain. And so I pray my Saviour, no matter how I plead, To give not mostly what I ask but what I mostly need.[42]

The following appreciation by John J Leahy appeared in the pages of The Kerryman:

Twentieth-century writers with old-fashioned styles do not usually please or impress but David Leahy who, whether he wrote poetry or prose, had an old-fashioned style, held the reader’s attention. His book, Musings of a Kerryman, contains a selection of articles which might have been written by a contemporary of Dickens and a selection of poems which might have been written in Shelley’s day. At drawing, too, he was skilled, and for a number of years the Christmas number of The Kerryman included a sketch by him of Santa Claus attending to his work. ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ was, perhaps, his best poem, but ‘The Invalid’s Room,’ written a short time before he died, reached a high standard too. One has the feeling that, had his health not failed, he would have emerged eventually as an essay writer. Good essay writers are few, but a study of David Leahy’s latest articles suggest he would have made the grade.[43]

J D Harnett

James Daniel Harnett of Abbeyfeale was born in 1871. He worked as a journalist, auctioneer and merchant. In 1908, he published a tribute to Rev William Casey, Parish Priest of Abbeyfeale, which has recently been reproduced by Castleisland District Heritage in conjunction with Abbeyfeale Community Council.[44]

James Daniel Harnett died at his residence in Main Street, Abbeyfeale on 4 January 1951. A sketch of his life can be read on the website of Castleisland District Heritage.[45]

Other Writers for The Kerryman

On production of the Kerryman calendar in 1934, welcomed as ‘a very acceptable souvenir,’ a writer using the name ‘Observer’ mentioned other writers not included in it:

Some were a little disappointed to find a few of the leading lights missing from the group. If there are a few absent ones whose names we should like to mention in this regard, it is very hard to overlook the mighty John Marcus, who rules like a monarch in his own peculiar sphere.[46] P.F. [Patrick Foley] is another brilliant writer whose features we should like to become familiar with, for the simple reason that his heart and soul seem to be steeped in purely Gaelic affairs.[47] Then there is the Mystery Man who writes with a roof of ‘Kerryisms’ over his head.[48] He appears to be a kind of Job’s Comforter, who wields a facile pen for the benefit of those seeking water supplies, sewerage schemes, housing grants, as well as multitudinous other boons so essential for the comfort of mankind. Mrs M Glover is another lady who is capable of writing some pretty poems.[49] We suspect that D M Brosnan is a very meek young man who wanders leisurely over hills and dales in order that he might be able to give us first-hand information as regards the different phases through which nature is passing. This he usually succeeds in doing very pleasantly when he steers clear of the avenues leading to mysticism. Then we have a powerful band of anonymous writers led by ‘Specs’ who keep us in touch with all the latest reports and rumours.[50]

While the identities of Observer and Mystery Man, whose ‘Kerryisms’ column appeared for decades, is open to research, the last named, D M Brosnan and ‘Specs,’ were brothers, Daniel and Liam, who lived at Close Cottage, Castleisland.[51] Daniel contributed poetry under his own name in the 1920s and 1930s.

The following lines are taken from his composition, ‘Those Crosses by the Way’:

By the crystal Maing you’ll wander, and the height of daisies yonder – By Leigh or Laune or Cashen brown you’ll rove on Easter Day, ’Mid greening woodland bowers, bedecked with early flowers, Oh, mute and white they’ll greet your sight, those Crosses by the way. But they tell a moving story, of a darksome day and glory, Of the rough red way to glory, that gallant feet have trod. Deep ’mong the shamrocks rooted, as pure and unpolluted, They symbolise to human eyes the dearest gift of God.[52]

He died in 1941:

The gentle poetic soul of D M Brosnan passed to its reward at his home, Close, Castleisland in the sweet twilight of 19th June 1941. The gentle bard of old Ciarraighe was laid to rest at Killeentierna with immemorial generations of his kin. A great funeral was proof of his popularity and the esteem of many friends.[53]

His brother Liam, writing under the pen-name of ‘SPECS,’ was Castleisland correspondent. He is remembered locally as a quarryman who worked for Rhyno Mills, Castleisland.

Liam Brosnan died in 1945:

The readers of The Kerryman and his Castleisland relatives and friends regret the death of Liam Brosnan – ‘Specs’ – who was its Castleisland correspondent in the late twenties and in the nine-thirties. He and John Marcus O’Sullivan, both well-read men, with strong literary leanings, every week enlivened the pages of The Kerryman by their caustic comments on economic and political events. Liam’s brother, Dan (RIP) published many of his best poems – traditionally Irish in form and spirit – in The Kerryman. Liam died peacefully in his country cottage at Close, fortified by the rites of Holy Church.[54]

Their sister Minnie was in her mid-nineties when she died at Close in 1979, after which the Brosnan cottage fell into ruin.[55]

___________________________

[1] The calendar was issued with the 13 January 1934 edition. [2] Kerry News, 12 January 1934. [3] Further reference, http://www.odonohoearchive.com/remarks-on-the-literature-of-t-m-donovan-castleisland/ and http://www.odonohoearchive.com/kerry-historian-t-m-donovan/ [4] T M Donovan raised a memorial slab of Carrara marble to commemorate his brother, Father John Donovan, SJ, executed by Mr P O’Reilly Monumental Works, Church Street, Castleisland: ‘It is intended to be placed on the family vault in St Stephen’s, where repose the ashes of one of the greatest churchmen of our time, world-renowned alike for his scholastic attainments and his virile championship of the Faith. The work is rarely delicate and beautiful. A chalice set in an aura and partly enfolded by an exquisite rose-wreath, surmounts the inscription in gilt lettering – a very masterpiece of the sculptor’s art. The distinguished Jesuit’s no less gifted brother, Mr T M Donovan, is responsible for this slab or rare beauty, which shall endure whilst a stone remains upon a stone in our renowned old church, and reflect an added lustre on the master hand that fashioned it’ (Kerry Champion, 26 August 1933). The memorial slab does not seem to have survived but an image of it is held in the archive of Castleisland District Heritage. [5] His name is also given as Maurice Michael Vincent Reidy. Thanks extended to Marie H Wilson, Tralee, for discerning his full name. It is worth noting here another of the same name, Miss Mary E Reidy, who contributed poetry to the Kerry press in the 1930s: ‘A young Oxonian’ ‘who sheds still another lustre on Oileann Ciarraighe, in addition to that magnificent translation of a few weeks ago’ (Kerry News, 23 November 1932). [6] Revised and reissued in 1905. A copy of the first edition is held in James Joyce Library, UCD. [7] Killarney Echo, 21 February 1903. The account in full: ‘The Castleisland Castle. I am standing tonight at the base of a ruined castle in the heart of the Kingdom of Kerry. It is an ideal evening in July, and the warmth of the midday sun is toned down to a delightful and cooling freshness. Towards the west the last faint crimson streaks of a glorious sunset are disappearing beyond the hills leaving a misty twilight in its wake that will linger for an hour – an hour to be revelled in by the dreamer and the poet – ere it is swallowed up by the shades of night. The ruin stands in a fertile valley that extends ten miles or so, until broke by a range of hills towards the west. From where I stand I can see the high peaks of MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, their bold outlines growing more hazy in the deepening twilight. Around the base of the castle the River Maine, here a small stream, ripples lazily to the sea. The Spirit of Peace broods over the scene, and the quietness that reigns is only occasionally broken by some sound from the little town beyond. A ruined castle! Not much to look at now, as it lays shattered into fragments, so scattered as to defy the antiquarian to trace its original plan. One angle of the ancient pile still rears its head proudly above the rest, and seems to groan with feudal pride at the wreck of its former greatness. And to think that these scattered heaps of stone once constituted the component parts of the strongest fortress in Desmond. A bulwark of strength against the enemies of the powerful Geraldines who flung back defiance from its walls, alike to Irish kern and English trooper. A fortress that stood for more than 400 years – most eventful years in Irish history – every stone of which could tell a tale of warlike and bloody deeds, of sieges successfully resisted, or brave men and noble and beauteous women, of romance, of love, of poetry, and of death. The castle was erected in the year 1227 by Geoffrey De Marisco or Geoffrey Morris, as Dr Smith calls him in his History of Kerry and the annals of that once powerful Geraldine family can be read from the varying fortunes of The Castle of the Island of Kerry. This old ruin saw the transition of the Geraldines – who once ruled Cork and Kerry, and, in fact, the greater portion of Munster, with more than kingly power – from fierce feudal lords to chieftains more Irish than the Irish themselves. As early as the year 1345 this development had set in, as in that year it was taken after a vigorous siege by Sir Ralph Ufford, the English Lord Justice of Ireland, it being then held by Maurice Fitzthomas Fitzgerald, the first Earl of Desmond, by Sir Eustace Le Poer, Sir William Grant, and Sir John Catterell, who were all executed. These knights, whose names betray their origin, were at that time the Earl’s principal followers, he being at the head of a band of gentlemen known as the Knights of English descent, in opposition to those of English birth. So that even the first of the Earls of Desmond was somewhat of a believer – tough in a crude and imperfect manner – of an Irish Ireland. In all the wild forays, the battles, the skirmishes, the cattle raids – at once time against a neighbouring Irish clan, at another against an English Deputy, Governor, or Lord Justice, or perhaps, some Norman baron – that the Geraldines engaged in, they looked to the Castle on the Island of Kerry as their great haven of safety. Safe inside its walls, they were able for centuries to bid defiance to their enemies. Here in the neighbourhood of this castle the second Earl, the gentle poet, Gerald, over whose name tradition has woven a halo of romance, was foully murdered, and in a wood not seven miles distant the last, and, by all means, the noblest of them all, another Gerald too, was done to death by an Irish soldier in the English service on a bleak November day in 1583. Truly there are episodes in our chequered history that we would willingly forget and one of them is the manner in which the last of the great Desmond Earls met his end. A brave and gallant soldier, a born leader, a hero – combining in his own person all the chivalry of his Norman ancestors and the dashing valour of an Irish chieftain – a courtier without servility, a gentleman with all the qualities of heart, mind and manners that is associated with that sacred and much abused name; there was no honour to which he could not aspire if he would but place expediency above patriotism and religious principles. He would not, however; and the result was that the almost regal power of his illustrious house was shattered, and his castles, domains, wealth and honour divided up amongst the vandals who would have trembled before him in the days of his power. A miserable day it was – that in which the cur dogs ran to earth their noble quarry in the wood of Glenaginty – miserable because even after the lapse of more than three centuries, it brings a blush of shame to our cheeks as we read the squalid tale. The great Geraldine, deserted by all but a few humble and trusted followers, who, faithful even unto death, would not leave him in the black days of ill fortune. In imagination we can picture him seated near the fire in a peasant’s cot, his noble head sunk heavily on his breast, his hair hanging in the Irish fashion over his shoulders, his face thin and haggard from privation and care, his body gaunt and fleshless, his powerful arm before which many a sturdy British warrior bit the dust, his eyes bloodshot from want of sleep, but still flashing at times with a light that showed the indomitable soul within. The door of the cot is opened, and half a dozen troopers rush in. The foremost – Daniel Kelly – raised his sword and nearly cut off one of the Earl’s hands at a blow. The hunted man called out to them that he was the Earl of Desmond, on hearing which they dragged him from the cabin. The man that every spy in Munster was moving heaven and earth to discover. The man whose life was a stop-gap to the schemes of Elizabeth and all her ministers. A splendid prize truly for an English trooper of the O’Kelly clan, as he was rewarded by a pension of £20 a year for 30 years for removing this great obstacle. The losos of blood from the wound in the Earl’s arm caused him to grow weaker, and Kelly, thinking it would be too much of a burden to bring a dead body back to the camp, told the Earl of prepare for death. Lifting his sword he struck the Geraldine’s head off, and the headless truk of the last of the Earls rolled over on the sward. The head was sent to England as a present to Queen Elizabeth and was stuck on a spike for the populace to gape at until the flesh shrivelled away, the hair fell off, and all that was left of an Irish rebel was a grinning skull. Not far from the ruin is the little churchyard where the body reposes, and the spot where he was so foully murdered can still be pointed out. His memory lingers yet around the place, as a little winding road leading through the wood is known as Boher-na-Earla to the present day. As the autumn wind blows through the leaves above, it brings a sound as of a gentle wail to the listener’s ear, as if some spirit lingered eternally over the spot to mourn in shame and anguish the dark deed by which the great Munster chieftain met his end. And around the Kerry firesides old men on winter’s nights still breathe a curse on the recreant Celt whose hand struck down the noble Geraldine, as they tell the tale of the ancient glories of Desmond.’ [8] Report of wedding ceremony in Killarney Echo, 30 September 1905. [9] Address given at that time was 54 Marguerite Road, Glasnevin, Dublin. His short story, The Awakening of Lucas Stanley, set in Dublin in the days of Robert Emmet was serialised in the Weekly Freeman’s Journal in December 1914 and January-February 1915. [10] Copy held in Castleisland District Heritage, reference IE CDH 113. See review in Kerry News, 18 July 1927. It was reviewed in The Irish Monthly (Vol 55, No 648, June 1927, pp335-336) to which publication a number of articles also appear to be his work, including The Vision of Saint Columba (1931), The Mantle of Saint Columba (1931), Some Jesuit Pioneers (1932), Sister Mary of St Philip A Great Woman Educationist (1932), Mother Mary of the Passion (1932), A Great Nineteenth Century Convert: Mother Stuart of the Society of the Sacred Heart (1932). The Little Reverend Mother (1946) also appears to be his work. [11] He had two sons who both matriculated with honours from the London University. [12] Obituary, Kerryman, 4 August 1951. [13] Kerry Reporter, 11 February 1933. [14] Little more is known about Michael O’Regan though the death of a man by that name of Rose Villa, Rathass, Tralee, occurred on 5 February 1951 and was reported in the Irish Independent, 7 February 1951. [15] The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0407D, pp7-8 (Patrick Lynch, Ballyhorgan, Lixnaw). [16] Kerryman, 29 February 1964. [17] Kerryman, 17 January 2007. ‘’Pat O’Connor, a Tipperary man by birth, worked for a horse trainer named Hewson at Ennismore … his ‘Call to Arms to The Kerry Team,’ written in advance of the 1930 All Ireland final is one of his best poems.’ [18] Edition of 2 August 1963. Another full length photograph was published in the Kerryman, 21 September 1963. [19] Kerryman, 15 February 1964. ‘Readers of the older generation will have heard with regret of the death of Mr Pat Connor, who contributed numerous poems to this paper over his initials ‘P C’ in the late twenties and early thirties. He described in verse many of the hectic All-Ireland finals in which Kerry took part in this period, apart from other contributions such as ‘Why Men are Marriage Shy.’ He carried on a most humorous poetic controversy with the late Mrs Hanna McCarthy, Tralee, on ‘Bobbed Hair.’ But it is as a versifier of Kerry footballers and their All-Ireland battles P C will best be remembered. These poems won widespread popularity for the author and many of them were reproduced in the GAA supplement of The Kerryman published some years ago. Though a man of modest means, P C always subscribed to the Kerry team training fund. His Kerry team poems will serve as a monument to his memory.’ [20] ‘The Bobbed Hair, ’The Liberator, 5 July 1924. [21] See ’Retort to Bobbed Hair’ by K R in Kerryman, 26 July 1924 and P C’s response, ‘A Hair Raid on K R’ in Kerryman, 9 August 1924.. Also ‘Maursha,’ lines from ‘The Bird,’ Kerryman, 30 August 1924 and Farewell to P C and Hannah McCarthy by W T of Ballyrehan in Kerryman, 15 November 1924. [22] ‘Modern Girl,’ The Liberator, 26 July 1924. The views of ‘Modern Young Man’ were published in the same journal on 9 October 1924. Nancy Dillon of Mountcollins went to great lengths to explain precisely why women bobbed their hair (The Liberator, 18 September 1924). [23] The Liberator, 4 September 1924. [24] From five verse poem, ‘The Fashions’ by Mrs Hannah McCarthy, Caherciveen in Kerryman, 2 August 1924. Those who attempted to respond in verse were rapidly put down by Pat O’Connor. To lines written by Rogha Na mBan (Kerryman, 11 October 1924) he wrote: ‘Did you read those splendid verses by our friend from Caherciveen?/What a difference ‘twixt yours and hers, of poets she is a queen/She showed no sign of temper. No she’s far above that style;/The fashions she defended, then descended with a smile (The Liberator, 14 October 1924).. [25] ‘The Bobbed Hair and Fashions. To Mrs Hannah McCarthy, Caherciveen,’ Kerryman, 13 September 1924. [26] ‘Bobbed Hair. To Mrs Hannah McCarthy,’ The Liberator, 7 October 1924. [27] ‘Why the Men are Marriage Shy,’ nine stanzas, The Liberator, 7 July 1925. [28] ‘Reply to P C,’ nine stanzas, Kerryman, 1 August 1925. [29] Kerryman, 1 August 1925. Another wordsmith under the name ‘Candid Old Maid’ stepped into the affray in 1930 with ‘A Quiet Talk to P.C.’ but was quickly put down by O’Connor: ‘Sure yours are worthy shoulders, Hannah McCarthy’s cloak to bear,/And with the Queen from Caherciveen there’s few that could compare’ (Kerry Reporter, 31 May 1930). [30] Kerryman, 15 August 1925. [31] The Liberator, 25 June 1925. Pat O’Connor described himself as ‘in exile’ but his thoughts he said, were ‘ever climbing the green hills of Kerry in search of something that would enable me to start another paper war.’ [32] The Liberator, 4 October 1930. [33] Tuam Herald, 2 June 1951. [34] Kerryman, 6 March 1981. [35] Tralee Liberator, 24 April 1926. ‘Thomas Kirby, whom we suspect to be ‘The Trapper,’ gives us interesting items in verse and prose when we find him in a good mood’ (The Liberator, 7 April 1934). [36] Kerry Reporter, 9 July 1932. ‘One’s eye is caught by the title on the cover of the first volume emanating from the gifted pen of our old ‘Kerryman’ friend, ‘The Trapper’.’ The authors utilised their Irish names, Miceál Ua Rioghbhardain BA NT and Tomás Ua Ciarrbhaic in the publication. [37] The Liberator Tralee, 23 July 1932. [38] Issue of 26 August 1933. [39] The Liberator Tralee, 2 December 1933. [40] ‘Thomas Kirby taught at a school in Tubrid and used to write for The Kerryman under the pseudonym The Trapper’ (Kerryman, 13 April 1990). [41] The book was advertised for sale in January 1950. See advertisement in Kerryman, 7 January 1950. Enquiries to Shamrock House, Oliver Plunkett St, Cork. Price 1/6. A short review appeared in the Irish Examiner, 10 January 1950. [42] The Kerryman, 8 March 1952. Micheal O Dalaigh published a poem in memory of David Leahy in the same edition. [43] The Kerryman, 15 March 1952. [44] The revised booklet, A Sketch of the Life of Rev Wm Casey, PP of Abbeyfeale (2022) contains a note by Brigid Harnett, granddaughter of J D Harnett, and is available from Castleisland District Heritage. [45] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-peoples-priest-rev-william-casey-of-abbeyfeale/ ‘The People’s Priest: Rev William Casey of Abbeyfeale’ for a sketch of the life of J D Harnett. [46] The Liberator, 7 April 1934. ‘Even though his ship, which is generally laden with facts and figures often encounters bad weather, he never leaves his post at the helm until it again anchors in calm water.’ Killarney-born John Marcus O’Sullivan (1881-1948). Further information in Dictionary of National Biography. [47] The Liberator, 7 April 1934. ‘Mr Patrick Foley, Chairman of the Kerryman Ltd, of which his uncle the late Maurice Brosnan was a founder, died in the Bon Secour Hospital, Tralee yesterday. Aged 72, he was associated with the Kerryman for 45 years and was for a number of years editor. He was best known however by his initials, P.F. under which he wrote GAA notes and reports of matches in the Kerryman since the early 1920s and established a wide reputation for the soundness of his judgment on players and the affairs of the association … A native of Dingle, he captained the local team and taught in the Christian Brothers Secondary school there. A fluent Irish speaker and writer, he taught Gaelic League classes in Wexford, Co Clare and Tralee when he went to live and work there.’ Extract from obituary, Irish Examiner, 7 November 1966. Another by the name of Foley who wrote under a pen-name is noted here: ‘The funeral took place after Requiem Mass in Limerick on Wednesday of Mr Dermot Foley. Deceased, who was father of Dr T Foley, was a native of Kerry but spent many years in Limerick in the Customs and Excise from which he retired some years ago. His death severs a link with the early days of the Gaelic League for he was the author of the rallying song of that organisation, Go Mairdh ar nGaedhluinn Slan. Mr Foley, who was a native speaker, was a prolific writer on Irish under the pen name, Fergus [or Feargus] Finnbheil. He was a personal friend of Dr Douglas Hyde. Mr Foley’s translation of part of the Arabian Nights is a standard work’ (Kerry Champion, 17 March 1934). The Celtic Who’s Who records the following in its entry for Dermot Foley: Born St Brigid’s Day 1864. One of the earliest revival writers and teachers. First head master of Ballingeary Summer College, established 1904. Publications: Go Mairidh ar nGaedhlig Slan, 1897; An Maeleighinn; Finnsgealia na h Araibe 1908. [48] The Liberator, 7 April 1934. ‘Kerryisms’ (/‘Limerickisms’) news column appeared on the front page of The Kerryman from September 1904 until the late 1930s when it was moved to the inside of the paper. It was still appearing in the 1940s. [49] The Liberator, 7 April 1934. Mrs Glover’s compositions appeared in the 1930s. She was a resident of Dingle. An article about Billy Boyle, native of Castlegregory, who married Mary Glover from Dingle, whose mother, also Mary, wrote ‘Dingle Bay’ recorded by D J Curtin was published in The Kerryman, 6 July 1979. The following is from ‘Old Dingle by the Sea (An Exile’s Memory)’ published in the Kerry News, 30 November 1932: ‘Old Dingle! Dear old Dingle!/Though I am far from thee;/I often sit and ponder,/On days that used to be/And through an exile’s dreaming,/I watch the flowing tide;/Thy lighthouse over beaming;/Across the ocean wide.’ In 1938, it was reported that ‘two of Mrs Glover’s poems have been accepted by leading publishers in New York and London. One of the poems, ‘My Maid of the Mountains,’ has been accepted by the well-known American firm, The Columbian Music Publishing Co Ltd for publication in music setting. ‘Mavourneen,’ the other composition, has been accepted by a leading firm of music publishers in London’ (Kerryman, 20 August 1938). [50] The Liberator, 7 April 1934. ‘Taking them all round, The Kerryman writers are a brilliant group and their work is thoroughly appreciated by those at home and beyond the seas. As many of the contributors have never met, we hope when times improve the proprietors of The Kerryman will bring them all together and treat them to a real banquet. Here poets and writers can fraternize and get to know each other better. What a night of life and jubilation that will be. The poets of course will give us original songs and recitations while the purveyors of prose will give us snatches of Irish wit and humour. We expect P.C. will come escorted by a heavy bodyguard for fear his fair adversaries might assassinate him. Of course nothing less than an armoured car will do to accompany John Marcus to protect him from both friends and foes. At any rate it will be a gala night for Ireland if ever all these assorted characters get together. Oh boy! And the night shall be filled with music,/And the cares that infest the day/Shall fold their tents like the Arabs,/And as silently steal away.’ [51] The district known as Close, Castleisland, encompasses the boundaries of the townlands of Caheragh, Tullig and Coolavanny. [52] Kerryman, 11 April 1925. [53] Kerryman, 28 June 1941. [54] Kerryman, 4 August 1945. Notice composed by T M Donovan. Census of Ireland 1911 provides the following information for House 12 at Tullig which may relate to this branch of the family: Michael Brosnan age 72 Mary Brosnan age 69 Bessie Brosnan age 41, William Brosnan age 34, Mary Brosnan age 22, Dan Brosnan age 13 … 10 children born, 7 then living. [55] ‘The death took place of Miss Minnie Brosnan of Close. Deceased in her mid-nineties lived alone and was a sister of a some-time correspondent of this newspaper who wrote under the pen name ‘Specs’ (Kerryman, 19 January 1979).