Still may Time hold some golden space Where I'll unpack that scented store Of song and flower and sky and face, And count, and touch, and turn them o'er – Rupert Brooke

For many, coffee shops play an important part in the social calendar. Castleisland boasts a host of them, and many an important or irreverent conversation takes place over a flat white or a cup of tea. They offer a good meeting point for many reasons, and not always just social.

Historically, in days when the newspaper played a more prominent role in communication, coffee houses were important places to meet and discuss the news and politics of the day.

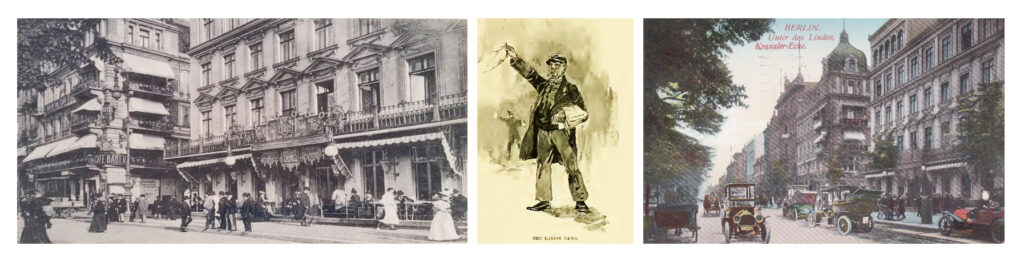

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Kranzler family of Austrian descent had a coffee house in Berlin.[1] It was located at the corner of Unter den Linden and Friedrichstrasse which became known far and wide as Kranzler’s Corner:

Kranzler’s was the first place in Berlin where day by day the news from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 was posted. Fifty years before that, when European politics practically spelled Metternich, Johann Kranzler, a Viennese pastry-cook, came to Berlin and established a Viennese café on a small scale at the now famous Corner. Viennese dainties and Viennese daintiness won speedy recognition. Kranzler in time became Royal Provider to the old Emperor William. He was a favourite of the Prussian monarch, and when that monarch went his long way via Sedan to be acclaimed German Emperor at Versailles, Kranzler’s was the first place to which Berlin flocked to read the daily reports. Look back through the novels of the ‘foundation-years,’ 1860 to 1870, hardly a one of them escapes mention of Kranzler. Latterly a few have been written by young men who have forgotten Johann, but the thing is still a tradition.[2]

In 1911, Johann’s second son, Alfred Kranzler, who also worked in the same business, passed away and Charles Tower, a writer and journalist working in Berlin, reported on Alfred’s death.

Tower appeared less than complimentary about Kranzler’s Corner:

Look up an old Baedeker, and somewhere under the ‘sights’ of the Linden or under ‘Cafés’ you will find the Café Kranzler. It was marked with a star. The trusting tourist, expecting some superb palace worthy of the chiefest promenade in the Kaiser-city, walked to Kranzler’s, nine times out of ten, missed it. A friendly Diensmann, in red cap, possibly guided him thither, and – the tourist was indignant. A dismal little pastry-cook’s shop, with a narrow dusty ledge outside on which, by crowding a little, perhaps twenty people might take their coffee with the maximum of discomfort. Such is Kranzler’s. And yet time was when Baedeker marked it with a star![3]

‘The star has gone from Kranzler’s,’ wrote Tower, ‘and yesterday old Alfred Kranzler himself followed the star.’

Tower turned his attention to Kranzler’s competitor:

Opposite Kranzler’s is one of the very best cafés in the world, known to every tourist, and long since the inheritor of Kranzler’s star, the famous ‘Bauer.’ It is difficult to think of an important European newspaper which you cannot read there: all the editions of the Almanach de Gotha are on file, with all the address books of every important city in the world. Its magnificent upper balcony commands the Linden so that one can ‘see the Kaiser go by’ (the principal enthusiasm of American visitors to Berlin) without the discomfort of the dust, and to accompaniment of as good coffee as you shall find anywhere.[4]

‘And yet,’ observed Tower, ‘any day in summer you will find that narrow, dusty, cramped gangway outside Kranzler’s overcrowded by just the people who are always where ‘one must be’ – Lieutenants of the Guard, courtiers, councillors and captains.’

But now that Alfred Kranzler was dead, Tower imagined the Kranzler coffee house was ‘doomed to destruction’ for ‘Alfred leaves no sons, and the dynasty of The Corner is extinct.’[5]

The Kranzler Tragedy

As Tower contemplated the future of Kranzler’s,[6] he also gave consideration to an individual closely associated with the establishment:

As you leave Kranzler’s you will see to the left, some forty or fifty paces along the Linden, on any day when it is not pouring in torrents, an old woman, wearing an old velvet bonnet, a shawl, and rough clothes. She carries what appears to be her sole portable property in a big handkerchief of many colours. She mumbles to herself and stands looking steadfastly from her sunken eyes towards the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin’s Arc de Triomphe. None molests her. She is as much part and parcel of the Linden as the Bristol Hotel behind her.[7]

‘Occasionally,’ remarked the author, ‘someone gives her a nickel, or even silver. In almost all weathers, and at every season of the year, she is to be found at her post, ever watching, and this is her story’:

Forty years ago, as a young girl waiting for her bridegroom, she came out with all the rest of Berlin to watch the triumphant troops march behind that column of captured French colours to the Palace. One by one the companies went by, regiment after regiment, until all had passed. But the bridegroom was not there. She waited until the troops had dispersed and the crowd had gone home, and the tumult and the shouting died. And she waits still. But the bridegroom tarries. This, after all, is the Tragedy of Kranzler’s Corner.[8]

The woman, known by all as ‘Linden Julie’ or ‘Julia of the Limes,’ occupied a niche near Kranzler’s Corner on the Unter den Linden, standing beside a small bundle, looking steadfastly towards the Brandenburg Gate for the return of Lieutenant Birkfeld, who she lost in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

In 1912, Linden Julie was found in an exhausted condition on the street and, dangerously ill, was conveyed to the charity hospital:

Linden Julie is a queer old crone, who every day and in all weathers stood outside the famous Kranzler Café, dressed in a queer, old-fashioned costume, with poke-bonnet and shawl, and bright-coloured petticoat. One legend says that she is a Polish Countess, who was deserted by her husband. But there is another and a genuine Berlin tradition which points to her having been a young bride whose husband went to the war in 1870 and never returned.[9]

Over the course of forty-one years, vain attempts were made to convince Julie of the hopelessness of her wait, but she persisted until her watch became a monomania.[10]

Linden Julie’s wait came to an end on 7 May 1913:

Linden Julie, who took her name from the Unter den Linden thoroughfare on which she kept a vain watch daily for the return of her soldier lover, died on Wednesday. Her lover failed to return from the Franco-German war in 1871. She never lost faith that he some day would turn up, and in rain or snow, huddled up in a shawl, kept watch on the streets, each year growing more ragged and white-haired. The police made an exception in her case in the rule which does not allow loiterers on the street, as they had compassion for the faithful Julie.[11]

There can be no doubt that Linden Julie formed the subject of many a conversation in Kranzler’s, and further afield. Her identity and her tragic plight still remain open to discussion.

Charles Tower, who took such pity on Linden Julie, died in England on 17 March 1944. His publications include The Moselle (1913) Germany of To-Day (1913) Along Germany’s River of Romance, the Moselle: The Little Traveled Country of Alsace and Lorraine: Its Personality, Its People, and Its Associations (1913) and Changing Germany (1915).[12]

A memorial to Alfred Kranzler (5 January 1841 to 26 February 1911) and his father, Johann Georg Kranzler (1795-1866) is located in the Cemetery Dorotheenstaedtischer Kirchhof II.[13]

______________________

[1] The Kranzler coffee house was opened in 1825 by Austrian born Johann Georg Kranzler (1795-1866), the son of a farmer by the same name. Kranzler had trained as a confectioner in Vienna and went to Berlin in 1816 as personal cook to the Prussian Chancellor, Karl August von Hardenberg. He gained citizenship in Berlin in 1824/1825 for the sum of 25 Reichsthaler. [2] ‘Kranzler’s Corner’ by Charles Tower, The Daily News, 2 March 1911. The following references about Kranzler’s Corner are taken from The Great Streets of the World (1892) by Richard Harding Davis, Andrew Lang, Francisque Sarcey, Isabel F Hapgood, W W Story, Henry James, Paul Lindau: ‘Upon the corner of Friedrich-Strasse, ordinary known as Kranzler’s corner, were held those mass-meetings where in the spring of 1848 under the pretext of conferring about the popular welfare, the good Linden-Muller, Held, Eichler, and other friends of the people pronounced pompous orations, while the wildest kind of fun raged all around. Here arose those grotesque popular chimeras, the most unbelievable yarns about the ‘approach of the Russians,’ who had been summoned by the Prince of Prussia to encircle and starve out Berlin in order to bring that dangerous nest of demagogues to reason and to restore the royal authority!’ (p194) ‘Kranzler’s far-famed Conditorei on the corner of Friedrich-Strasse, which is really the last of its type and has gallantly resisted all the attacks of modernness’ (pp187-188) ‘Here, during the late evening and night, Berlin has in fact a thoroughly cosmopolitan character, and its evening holiday is longer than that of the other great European centres, Paris, London and Vienna. At this famous corner there is something going on until four or five o’clock in the morning. It never ceases, really, and the ending of the night’s frolic and the beginning of the day’s touch hands’ (p201). [3] ‘Kranzler’s Corner’ by Charles Tower, The Daily News, 2 March 1911. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. ‘Moreover,’ he added, ‘at the Red House, where the Police President reigns, they are considering hateful things like regulation of traffic, and this Kranzler Corner needs regulation as badly as any because it stands at the entrance of the narrowest part of the Friedrich-strasse, which is something like Fleet-street in the days of Temple Bar. The half-masted flag over Kranzler’s today is an omen that the house, like its star, is doomed to destruction.’ ‘The Kranzler corner is probably the most expensive corner in Berlin. At the recent supervisory board meeting of the hotel company, the takeover of the Kranzler Court Confectionery was approved for an annual lease of 85,000 marks for a period of 20 years. However, as the confectioner announced, the operating company has secured the right of first refusal to purchase the grand piece within five and a half years at a price of 2 million for the 20 square acres of land, so that the square acre would cost exactly 100,000 marks. An additional 100,000 marks were paid for permission to continue running the company’ (Morning Leader, 22 November 1911). [6] It was probably Charles Tower who in 1932, while was working for the Yorkshire Post, reported on the evolution of the café: ‘The famous Kranzler Corner, where in the café of that name in the Unter den Linden, every visitor to Berlin used to sit and watch celebrities of the day pass to and fro has migrated to the west end’ (Yorkshire Post, 16 May 1932). He added: ‘A new Corner has been established in the home of the famous Café des Westens. But this café had only languished, a ghost of its former self, since the inflation period when a new coat of paint and ultra-modern furnishings drove all its Bohemian patrons away. It was no longer the same place that Rupert Brooke knew. One by one Berlin’s old-established centres of social life have closed their doors, tried, as often as not, to re-open under the same name in a new neighbourhood and failed miserably. Everybody wishes ‘Kranzler’ good luck, hopes the best and fears the worst’ (Yorkshire Post, 16 May 1932). A note on the Café des Westens can be read here: https://www.cafe-groessenwahn.de/en/more/the-story/ In 1945, it was reported that ‘Kranzler is the word which in Berlin was associated with all that was urbane. It is a great café on the Kurfuerstindam, from which comes the rich aroma of coffee, pastries and all those rare things which must now have disappeared from the Spartan diet of a beleaguered Germany’ (Nationalist and Leinster Times, 21 April 1945). An account of Kranzler’s Corner (Ecke) is given by Paul Cleave in Leisurely consumption, the legacy of European cafes (2016). [7] Ibid. The Hotel Bristol was destroyed by an Allied Air Raid on 15 February 1944. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hotel_Bristol_%28Berlin%29 [8] ‘Kranzler’s Corner’ by C Tower, The Daily News, 2 March 1911. [9] Dundee Telegraph, 5 April 1912. [10] Ibid. ‘Julie at first stood at the corner of the Linden watching the troops return, and always expecting her husband. Despite gentle attempts that were made to convince her of the hopelessness of it, she persisted in waiting and watching until her watch became a monomania. She was protected by the police, and often received doles, though she never begged. It should be added that she was unable to answer questions.’ [11] Strabane Chronicle, 17 May 1913. Julie’s death was widely reported, in which the man she awaited, Lieutenant Birkfeld, is occasionally spelt Birkfield. [12] Journalist and author, Charles Tower (1878-1944) was born at Wethersfield, Essex, eldest son of Rev Charles Marsh Ainsley (Ainslie) Tower (1849-24 June 1927), Vicar of Shoreham, and his wife Henrica Jane (1855-1919, married 1875), daughter of Major Henry C Watson, 37th Brigade Depot Bristol, and granddaughter of Sir Robert Alexander Chermside of Paris. Charles Tower was the brother of Katherine Frances Tower (1888-1960) and Rev Henry Bernard Tower (Head Master of St John’s College, Hurstpierpoint, Sussex) whose only son, from his 1912 marriage to Miss Stella Mary Hodgson, only daughter of the Archdeacon of Lindisfarne, Sub-Lieut William Bernard Lyulph Tower RN, HMS Somali, was Killed in Action on 3 June 1940. Tower was educated at Marlborough and Oxford and was subsequently Berlin correspondent of the Morning Leader and later the Daily Mail. He gained insight into the German character and was therefore never deceived by propaganda put out by German militarists. He was leader writer for the Yorkshire Post from 1923 until the outbreak of war when he joined the Ministry of Information. He married Edith North Paddon (1879-1961) by whom he had a son, Charles H N Tower (1907-1928) born in Berlin, who was killed in a road accident on 11 April 1928, and four daughters including Kathleen Edith Amelia Tower (1910-1994), Irene Violet Tower (1917-1995) who married Major Eric William Drown in 1944, and Margaret Josephine Tower (1922-2006), born in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Charles Tower was said to bear a remarkable facial resemblance to Dr Jameson of the Jameson Raid. Charles Tower died on 17 March 1944 aged 66. In an obituary, it was said that Tower ‘never had any doubt as to Hitler’s influence on Germany. He had by heart passages from the dictator’s Mein Kampf and his orations to the German people that, in Tower’s opinion, always stamped the Fuehrer as a megalomaniac and gangster’ (Yorkshire Post, 21 March 1944). A photograph of Charles Tower appears in The Yorkshire Post Two Centuries (1954) by Mildred Ann Gibb and Frank Beckwith. [13] The progress of Café Kranzler can be found at this link https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caf%C3%A9_Kranzler.