Castleisland District Heritage has recently acquired a set of photographs of the St Patrick’s Day Parade in Cahersiveen which date to circa 1998.[1] Among the clowns on bicycles, the village blacksmith and the parading musicians are floats promoting Iveragh Sports Complex, the Cahersiveen Celtic Music Festival and the Daniel O’Connell Walking Festival.[2]

The scene, repeated across Ireland and far further afield – whatever the weather – is what being Irish is about. However, in 2020, the celebrations were cancelled, and this year (2021) the streets are set to remain empty and silent once again.

Origins of St Patrick

According to one authority, St Patrick, the Apostle of Ireland, was born in the Vale of Rhos in Pembrokeshire, about the year 373 AD. A little about this district is found in a book written in 1673 and dedicated to Charles II:

St Davids, ill seated in a barren soil, within a mile of the Sea-shoar, and on the small River Ilen, being destitute of wood, so that it is exposed both to wind and storms. It is called by the Britains Tuy-Dewy from Devi a Religious Bishop who made it an Episcopal See and was once the Metropolitan See in the British Church, and long time continued the Supream Ordinary of the Welch. And here lived Calphurnius, a British Priest, whose wife was Concha, sister to St Martin, and both of them the Parents of St Patrick the Apostle of the Irish.[3]

The mists of time, however, have obscured the place and year of the saint’s birth – some maintain it was Scotland in about 385 – and also his parentage:

According to his pedigree, which I have got in an old manuscript, and another I have seen in the British Museum, which runs thus: Patrig St ab Alvryd, ab Gronwy, o Wareddawg yu Arvon, that is, St Patrick, son of Alvryd, son of Gronwy, of Wareddawg, in Carnarvonshire … His original Welsh name was Maenwyn, and his ecclesiastical name of Patricius was given him by Pope Celestine, when he consecrated him a Bishop, and sent him a missioner into Ireland, to convert the Irish, in the year 433.[4]

Efforts to return to the source of the stream, so to speak, generally add to the confusion. ‘Thanks to recent criticism and research,’ wrote Rev Ebenezer Josiah Newell, Head Master of Neath Proprietary School in Wales, in 1890, ‘it is now possible to distinguish among early documents between the false lives and the true: between the legendary imposter who has been dignified by Patrick’s name, and the historic Patrick, the saintly Apostle of Ireland’ – before adding to the tangle another year of birth for the saint of 394.[5]

Perhaps the last word on the subject should go to St Patrick in his Confessio.

Fasting and Fish Pye

The fabulous stories of St Patrick, the Apostle of the Irish, come down to us richly embellished. He is credited with writing 365 books of A B and Cs, founding 365 churches; consecrating 365 bishops; ordaining 3000 Presbyters, converting and baptizing 12,000 men in the region of Connaught and baptizing seven Kings, the sons of Amolgith. He fasted for forty days on the top of Mount Eli, and obtained three petitions from Heaven one of which was that no venomous creatures should ever infest Ireland.[6]

St Patrick is said to have lived to the age of 120 adding yet another layer of confusion to the cloak that surrounds him. The date of death that seems to be generally agreed on is 17 March in the year 461.

What is certain is that March the 17th is a date fixed in the national calendar for all things green, most notably the shamrock:

When Patrick landed near Wicklow, the inhabitants were ready to stone him, for attempting an innovation in the religion of their ancestors. He requested to be heard, and explained unto them, that God is an omnipotent sacred spirit, who created heaven and earth, and that the Trinity is contained in the unity; but they were reluctant to give credit to his words. St Patrick, therefore, plucked a trefoil from the ground, and expostulated with the Hibernians; ‘Is it not as possible for the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, as for these three leaves to grow upon a single stalk.’[7]

The symbolism of the shamrock in Ireland was remarked on in the English Court in the eighteenth century:

The Natives of that Country adorned their Hats with Shamarogs, which are composed of a Sort of Grass, called from its three Leaves Trefoil. Which Allusion is taken from St Patrick’s first propagating Christianity there, and establishing the Doctrine of the Holy Trinity.[8]

The Feast of Saint Patrick was celebrated in the English Court as a Collar-Day. In 1743, ‘His Majesty and the Royal Family wore Crosses in Honour of the Day.’ Overdoing the celebrations in England in the eighteenth century, however, came at a price:

Friday last, being St Patrick’s Day, the Tutelar Saint of Ireland, six Soldiers, Natives of that Country, having drank too largely in Commemoration of the Day, attacked and abused every Body that had the Misfortune to fall in their Way, among the rest, two Sailors were dangerously wounded. The Soldiers were brought up Prisoners of the Castle, where they remain under Confinement.[9]

In 1769, in Limerick, officers of the 27th and 47th Regiments and the Corporation of Limerick dined at ‘the three tons’:

The table was graced with fifty dishes in the true Hibernian taste, at the head was a Salmon pye four yards in circumference, and a pyramid of one hundred and eighty four jellies in the centre … the evening concluded with bonfires and illuminations ‘in honour of the land we live in.’[10]

St Patrick in the Arts

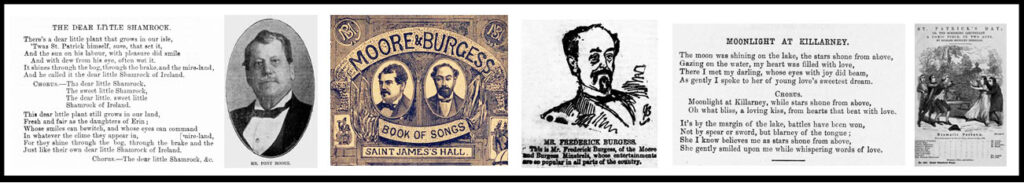

St Patrick has inspired a long and endless list of creative art representative of its time. St Patrick’s Day or The Scheming Lieutenant, a farce in two acts by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, was very well received during its first performance in Covent Garden in 1775. A century later, 1875, George Washington Moore sang for the first time the newly composed St Patrick’s Parade to a delighted audience.[11]

Closer to our time, a poem, ‘St Patrick’s Day in Exile,’ recognised the longing for home, all the more poignant on 17 March:

I’ve a letter from a sister in Ireland, And she says to her wanderin’ boy: ‘Dear brother, ’tis a shamrock I send you That I plucked ’neath the old rowan tree. On Patrick’s Day you must wear it, For the sake of ould Ireland and me.’[12]

There will certainly be a lot of making up to do when people can gather once again on St Patrick’s Day and with luck, it will be in time to celebrate St Patrick’s 1650th birthday (or thereabouts) – surely a special date in anyone’s calendar.

_________________________

[1] IE CDH 10. The photographs were taken by John and Dorothy Murphy, formerly of Seaview House, Waterville. The set includes two images of boats in the harbour. [2] Other images include Keatings, The Cosy Corner, the village blacksmith, and ‘A Day in the Bog.’ [3] Britannia: Or, A Geographical Description of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1673) by Richard Blome, p275. One genealogy suggests that Maenwyn Succat (otherwise St Patrick), Bishop of Ireland, was the son of Calpurnius (or Calprinn or Calpruinn Alpin) born in Kilpatrick, Ireland in 298, and Conchessa Alpin (Succat) born in Kirkpatrick, Ireland in 305. He had five siblings including Calpurnius Alpin and Tigridia Mawr, who died in 400. The dates suggest that St Patrick was more likely the grandson of this first named Calpurnius. [4] Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards (1794) by Edward Jones, dedicated to His Royal Highness, George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales, pp13-14. ‘Another thing corroborates this genealogy: there is a place by the sea-side in Meirionyddshire called Sarn Badrig, or Patrick’s Causeway; also he built a church in Anglesey called Llanbadrig; and there are meadows called Rhos Badrig.’ [5] St Patrick: His Life and Teaching (1890) by E J Newell. Parents are named in this work as Calpornus (or Calpurnius, son of Potitus, son of Odissus) and his wife Concessa. Reverend Ebenezer Josiah Newell (1853-1916) was educated at Worcester College, Oxford. He was ordained priest in 1891 and later served as rector of Neen Sollars, Cleobury Mortimer, Shrops from 1900-1916 (Dictionary of Hymnology). Among his publications, a volume of poems, The Sorrow of Simona, and Lyrical Verses (1882). [6] Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards (1794) by Edward Jones, pp13-14. ‘His life was written by Trychanus; by St Evin (Tripartite); and Ninian.’ [7] Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards (1794) by Edward Jones, pp13-14. ‘Then the Irish were immediately convinced of their error, and were solemnly baptized by St Patrick. St Patrick built several churches and seminaries in Ireland, that of Saball-Padbrig, or Patrick’s Grange, Domnach-mor Patrick, or Patrick’s great church; and the monastery of Armagh owed its foundation to him and was the principal school of Ireland.’ [8] Derby Mercury, 20 March 1752. [9] Caledonian Mercury, 21 March 1758. A more subdued affair took place elsewhere in the same year: ‘Friday March 17 being St Patrick’s Day, Titular Saint of Ireland, the Members of the Antient and Most Benevolent Order of the Friendly Brothers of St Patrick met at the Rose Tavern in Castle-Street from whence they went to St Patrick’s Church and heard an excellent Sermon, suitable to the Occasion, preached by the Rev Mr Sandys; after which they returned to the Rose, where an elegant Entertainment was provided’ (Poe’s Occurrences, 14 March 1758). [10] Caledonian Mercury, 1 April 1769. [11] George Washington Moore (1819-1909) was born in New York on 22 February 1819. He acquired the soubriquet ‘Pony’ by driving, as a youth, 40 ponies at the head of a circus procession in America. He was manager of an American minstrel troupe and later, in 1859, went to London, engaged by the Raynor Company. He met Frederick Burgess in Glasgow and they first performed in London at the Standard Theatre. In 1862, the company made its headquarters at St James’s Hall, London which it occupied for 44 years, the last concert taking place 11 February 1905 (the Moore and Burgess Minstrels were founded in 1871, known as Mohawk Minstrels from 1900). Moore resigned in 1894, and died at his residence, Moore House, Finchley, on 1 October 1909. He was buried in Brompton Cemetery (Funeral report, Dundee Evening Telegraph, 7 October 1909). His was first married to Elizabeth Totten, who died on 17 December 1882 aged 50, leaving a son and four daughters: George Washington Moore jnr (1862-1901), manager of Washington Music Hall in Battersea. G W Moore jnr married Louisa Towerzey at St James’s Church, Piccadilly on 6 March 1884. A son was born on 22 November 1886. Mrs Moore died from consumption on 5 August 1891 and was buried in Brompton Cemetery. Her husband died from consumption at the Star and Garter Hotel, Portsmouth, residence of Judd Green, to where he had gone for the benefit of his health, on 20 September 1901 aged 39. A report of his funeral at Brompton Cemetery stated his grave contained the remains of his mother, his wife and child ‘and the infant daughter of Charles Mitchell.’ Funeral reports, Sporting Life, 26 September 1901 & The Era, 28 September 1901. Mary Jane Moore, who married in 1868 to George Lewis Rackstraw; Martha Isabella Moore (1854-1913) who married Frederick M Vokes at St James’s Church, Piccadilly on 25th March 1873 ; Annie Matilda Rosina Moore who married ‘Eugene Stratton’ (Eugene Augustus Ruhlmann) on 15th November 1883; Victoria Alexandra Moore (1870-1911) who married the boxer, Charles Watson Mitchell (1861-1918) at Marylebone Registry Office on 4 November 1886. George Washington Moore married again, on 18 May 1884 in New York, to Louisa Jane Newman. He left provision in his will for his stepchildren, Louisa Frances Mynott Newman and George Washington Mynott Newman. The following notice was posted in The Referee, 16 November 1890: ‘On Saturday last, in her eighty-second year, died Mrs Mynott, the well-beloved mother of G W Pony Moore of the Moore and Burgess Minstrels.’ And in The Era, 9 November 1895: ‘In Memoriam. A Mynott. In loving memory of dear mother, who passed away Nov 8 1890. Ever missed by her affectionate daughter, Mrs G W Moore.’ Frederick Burgess (1827-1893) was born in Providence, Rhode Island. He had great taste in art, music and literature, notably dramatic literature; his collection was insured for £12,000. He was twice married. His first wife, Emma, died at Burgess Hall on 16 July 1882. He married secondly on 13 June 1883 to the actress Ellen Meyrick, niece of Mr and Mrs John Billington, at St John the Baptist parish church, Kentish Town. The following announcement was published in the Graphic, 3 June 1882: ‘Married on the 18th inst at St Mary’s Church, Finchley, by the Rev Samuel Bardsley, Carl Christoph Wilhelm, son of the late W Schoell Esq of Pheningon, to Florence Emma, only daughter of Frederick Burgess of Burgess Hall, Finchley.’ Frederick Burgess died at his residence, Burgess Hall, Finchley on 26 July 1893 aged 66. He was buried in Highgate cemetery, chief mourners, his brother Frank Burgess, Mrs Carter (sister) and Alice Burgess (niece). The following may be of use for genealogy: Died April 1851 in New York, John M Moore Esq, eldest son of the late George Washington Moore Esq of Upper Bridge Street, Dublin (George Washington Moore snr died in Dublin in 1833). [12] From ‘St Patrick’s Day in Exile,’ Dundalk Democrat, 17 March 1906.