‘If you shall take me into your service I shall do all in my power to do my duty faithfully and well’ – James Woods to the Irish Civic Guards, 25 October 1922

From the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty at 2.30am on the morning of Tuesday December 6th 1921, up until the official end of the Civil War on Thursday May 24th 1923, Ireland – and particularly Kerry –was in a state of violence and disturbance:

The fighting in Kerry was particularly bitter for a number of reasons: remoteness from Dublin; the character of the Kerry people; and the fact that many of the troops engaged against the Kerry IRA came from Dublin and had no empathy with country people[1] … Kerry and Mayo were never defeated in the Civil War.[2]

This is reflected starkly in the events which occurred in Scartaglin between Monday December 3rd and Thursday December 6th 1923, even after the official end of the Civil War. In his book, The Fallen, Colm Wallace describes Scartaglin in the year 1923 as ‘a hotbed of Irregular activity.’ By the time the first Gardaí arrived in the area at the beginning of that year, Scartaglin ‘had been without a functioning police force for a considerable period of time.’[3]

On the evening of Monday 3 December 1923, Sergeant James Woods became the first Garda killed in the emerging history of An Garda Síochána. Scartaglin man John Galvin, a former member of the committee of Castleisland District Heritage, pays tribute to his memory:

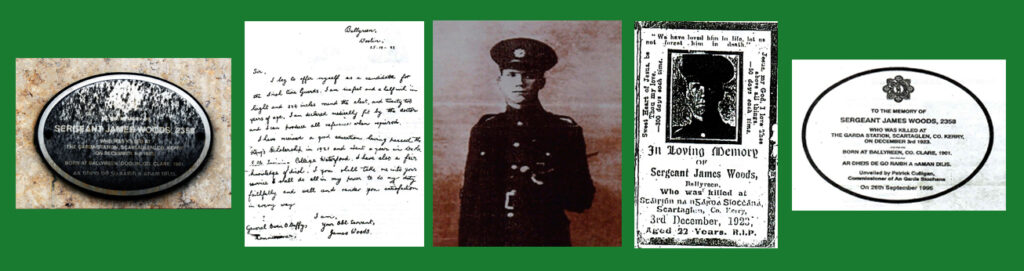

James Woods was born in Ballyreen, Doolin, Co Clare in 1901. He attended the local primary school and then went to the De La Salle Preparatory College in Cork, and subsequently attended the De La Salle Training College in Waterford. He then joined the IRA. In October 1922 he applied to become a Garda Siochana and was successful. He was sworn in as a member of that force on the 15th of November 1922, the swearing taking place at Ship Street Barracks in Dublin.

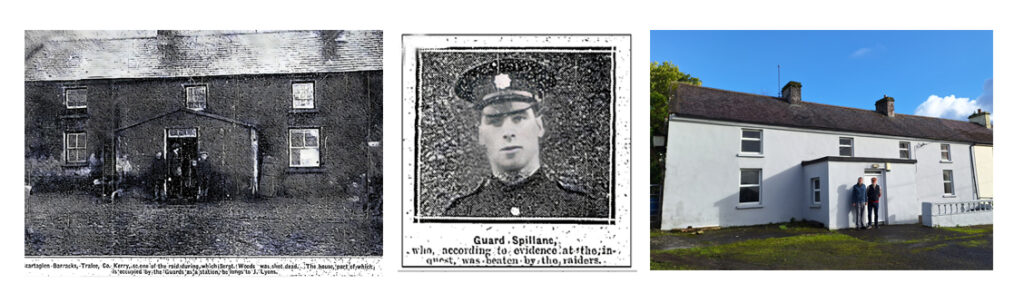

James’s first posting was to Bantry Garda Station in West Cork and he spent about six months in that town. On May 1st 1923 James was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and was transferred to Scartaglin Garda Station on May 30th 1923. The Garda Station in Scartaglin at the time was located in a house which is owned by the Lyons family just off the village green, and it is still standing today.[4] Again he spent about six months in Scartaglin on peace keeping duties.

On the night of December 3 1923 there was an armed raid on the Garda Station in Scartaglin and in the course of the raid Sgt Woods was fatally shot. It seems that the purpose of the raid was to get possession of Garda uniforms with a view to committing further crimes. About a dozen men armed with rifles were involved in the raid.[5]

The station orderly on duty on that fateful night in Scartaglin was Garda Pat Spillane who was a native of Blarney, Co Cork. Pat refused to take off his uniform despite a rifle being pointed at him only inches away and was forcibly stripped afterwards.

Sergeant James Woods was only 23 years of age when he died, and was the first member of An Garda Siochana to die on active duty in this country. On the day of his burial, General Owen O’Duffy, then Chief Garda Commissioner, gave a graveside oration and said, ‘Be not daunted, carry on your work. You are doing useful and valuable work for Ireland. Yield only in death.’

Sgt Woods certainly yielded only in death and paid the ultimate price for his bravery. General O’Duffy’s closing words were, ‘May the sod rest lightly over his immortal remains and may God forgive those who sent James Woods before the Judgement Seat of Our Lord without giving him time to make an Act of Contrition.’[6]

This year, 2023, marks the 100th Anniversary of the fatal shooting of Sergeant James Woods and the fact that this young man died at 23 years of age in the course of his duties should never be forgotten.[7]

The general consensus was that the Scartaglin raid, which lasted no more than ten minutes, was one of robbery and the shooting of Sgt Woods accidental:

The opinion is that the raid on the house where the Guards are billeted was in the first instance purely a robbery expedition, for the Guards receive three months’ salary together, and the robbers expected a big haul. But the robbers were disappointed for the money did not arrive until some day later. It is believed the death of Sergeant Woods was due to accidental shooting.[9]

None of the raiding party was ever brought to justice, and the killer was never identified.[10]

Requiem High Mass for Sgt Woods was celebrated in St John’s Parish Church, Tralee on the morning of Wednesday 5 December 1923 by Very Rev D O’Leary, PP, VG, Dean of Kerry. The remains were subsequently conveyed by motor car for interment in the family burial place in Co Clare.

A plaque to the memory of Sergeant James Wood was unveiled by Patrick Culligan, Commissioner of An Garda Siochana, at Castleisland Garda Station on 26 September 1995.[11] In May 2010, Sgt James Woods numbered among those honoured at the official opening of a Garda Síochána Memorial Garden in Dublin. Sgt Woods was represented at the ceremony by his nephew, Michael O’Halloran of Corofin.[12]

‘I know that this murder will be condemned in every home in Kerry’ – Oration of General Eoin O’Duffy at the grave of Sgt James Woods

James Woods, son of James Woods and Margaret Doherty, was one of a family of nine children, six sons and three daughters.[13] James applied to the Civic Guards on 25th October 1922, and on the 15th of November 1922, he was a member. Two of his brothers also served in the force.[14]

Con Woods, nephew of James Woods, has composed an intimate account of his uncle in which he recalls how proud his family was of the part James was taking in the ‘New Ireland’:

The family were very proud of James. The sadness of him leaving home was counterbalanced by the pride they had in him in the vital and important work he was going to undertake. Ireland could now have its own police force. It could, above all, now rule itself. British rule was gone from Doolin and from Ireland. Irish people could again own their own land. The landlords, after many centuries of occupation, were being banished. The War of Independence had ended. The Woods family, like the rest of the Irish people, no longer had to tolerate the vandalism and thuggery of the Black and Tans.[15]

Con also gives an assessment of the situation his uncle faced on 3 December 1923:

A twenty-three-year-old Garda Sergeant was faced with what no law-enforcing person wants. Would he defend his own personal position, the position of the Garda Station in Scartaglen, or could he, above all, stand for law and order in the New Ireland of the time? No one was to know, but seconds and minutes now were going to be vital for James Woods. He was unarmed. Even though faced with an armed gang, he decided that he would defend the law of the land. His decision was to do so and not meekly surrender. This decision was going to have appalling consequences.[16]

Con discourses on the impact of his uncle’s death on his family and wider circle and also reveals how the removal of his uncle’s remains from Co Kerry to Co Clare was ‘not to be a straightforward journey home for the family’:

It is hard to believe that anyone would interfere with the family in the midst of their great suffering and trauma but a gang of republican sympathisers blocked the road at some point in Co. Kerry with a horse cart and would not allow the cortege through. Thomas, James’ brother, challenged the gang. As the coffin was draped in the tricolour of the New Free State, he said to them, “Do you recognise the flag?” They replied, “No”. “Do recognise the coffin?” They replied, “No”. A standoff ensued in this lonely part of Co. Kerry.[17]

Patrick J Spillane

At the time of the raid on the Scartaglin Barracks, Garda Patrick J Spillane, who went on to serve in the force for almost thirty years, was also on duty and endured the brutality of the intruders.[18] His son, also Patrick, joined the force in 1967 and was assigned to William Street Station in Limerick. At the request of Castleisland District Heritage, Patrick shares his memories of events as told to him by his father:

By way of introduction my name is Pat Spillane. My father, Patrick Spillane, was a member of the Garda Síochána, serving from May 1923 until May 1952. His Reg Number was 3084. A native of Blarney, Co. Cork; born in 1901. He was a member of the Irish Volunteers/I.R.A. 1918 – 1922.

By December 1922, the Civil War had been officially over for some six months. Republicans had retreated to the South and to the West of the Country. Kerry had a huge Republican contingent and was referred to as part of the ‘Munster Republic’.

My father’s first station was Scartaglen in Co. Kerry. At 8.30 PM on the 3rd December 1923, Scartaglen Barracks was attacked by six armed and masked men. Colm Wallace (The Fallen) tells how ‘three of the armed men entered the Kitchen/Public Office. The room was crowded and present were Guard Spillane, Jeremiah Lyons, his wife and six children; and two local brothers, James and Michael Kearney. Sergeant Woods was in another room. James Kearney was hit in the face with the butt of a rifle and his nose was broken.’

My father was Station Orderly and was set upon and ordered to put up his hands; which he did. He was struck on the side with the butt of a rifle. They next dragged him towards a stairs and ordered him to climb up and they followed behind. When they reached the second floor he was ordered to strip. He refused saying he ‘was prepared to die in defence of his Garda uniform’. One of the men threatened to shoot him if he did not strip. He again refused and the raider said ‘if you do not strip it will be worse for yourself’.

He bravely stood his ground. He was badly beaten and forced onto a bed and they ripped his uniform from him. He was now only wearing his shirt; which he was told to remove. He refused. They eventually succeeded in taking his shirt from him. The raiders then took his watch and chain, and 30 shillings from his tunic pocket. They burst open his wooden chest and removed more money and clothing; which was also stolen. They forced open other chests of the Gardai and did likewise. They then ordered him to call Sergeant Woods. He refused. They threatened to shoot him again.

One of the raiders went downstairs calling loudly for Sergeant Woods. On hearing the commotion, Sergeant Woods arrived to the Kitchen. He was forced at gunpoint towards the stairs. As he reached the stairs he was prodded with a rifle near his neck. A shot went off. He was killed instantly. In the panic and commotion that followed, the raiders fled.

My father showed bravery and heroism that night, as a 22 year old Garda in an area of widespread civil unrest, in the midst of a Civil War; faced by armed and masked Anti-Treaty Forces. Con Woods, a nephew of Sergeant Woods, has covered the murder that took place on the 3rd December 1923 in more detail.

My father was in the following stations: Scartaglen, Castleisland 1923, to Tralee on the 18th June 1928. To Ballybunion on the 20th January 1931. To Listowel on the 16th May 1933. He was then transferred to Drimoleague on the 20th May 1934. Skibbereen was his last station; arriving on the 9th April 1935 until he retired on the 15th May 1952.

During the Emergency, from 1939 to 1945, he was seconded from the Gardaí and became District Administrative Officer of the Local Defence Force for the Skibbereen area.

From the Oration of General Eóin O’Duffy at the grave of Sergeant James Woods:

We will yield only in death, and Garda Spillane, the brave comrade of our Sergeant (James Woods), when addressing the cowardly assassins exposed the sentiments and feeling of every Officer and Garda when he said ‘I will die in defence of my uniform’.

I am glad to report that my father had a long and happy retirement from An Garda Síochána; lasting 29 years. A proud Corkman, who loved hurling, football and road bowling.

To conclude, my father stood tall when the need was greatest, and as a family we are all very proud of him. May he Rest in Peace. He died in St. Anne’s Hospital in Skibbereen in 1981.

To all those that joined An Garda Síochána during very difficult times – thank you.

Thanks to Castleisland Heritage Committee, Kerry Gardaí and the Garda Representative Association.

Continued Unrest

On Tuesday 4 December 1923, the morning after the attack on Scartaglin Barracks, a man named Con Horan was shot in a raid on a property at nearby Dromulton. From his hospital bed in Tralee Infirmary, Con Horan spoke about his escape from the armed raiders. He was, at the time, in the employ of Mrs O’Connor, a widow, at Dromulton, and on Monday evening retired to bed. In the room with him were Patrick O’Connor, son of his employer, and William O’Connor of Adraville. David O’Connor, another son of his employer, and Patrick Healy were sleeping in a bed in the same room:

About 6 o’clock on Tuesday morning there was a knock at the door, and Mrs O’Connor opened it. A man with a flash-lamp and a revolver entered, went upstairs to the room where he and the others were sleeping, and ordered them downstairs. Mrs O’Connor and her daughter followed them out screaming, ‘Where are you taking the boys?’ The man with the revolver fired three shots over the heads of the women.[20]

‘While the shooting was going on,’ said Con, ‘I got shot from behind under the left shoulder.’ After this he and the other four boys ran for their lives in their nightshirts. It transpired that one of the two raiders took a watch belonging to Mrs O’Connor’s deceased husband and when she protested he placed it on the floor and danced on it. Horan declared that none of the five boys in Mrs O’Connor’s house had heard anything at the time about the shooting of Sergeant Woods at Scartaglin, about a mile and a half distant.[21]

‘No man has a right to carry lethal weapons without the authority of the State’ – Cork Examiner

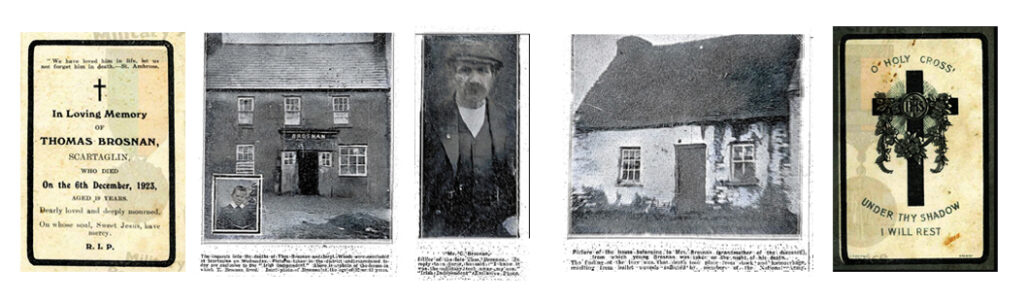

Two days later, Thursday 6 December 1923, the murder of 20-year-old Thomas Brosnan, son of a local publican, occurred on the road near the church in Scartaglin. Colm Wallace (The Fallen) provides the background in the aftermath of the shooting of Sgt Woods:

As the days went on with no apprehension of the culprits, larger numbers of troops converged on Scartaglen to root out the gunmen. Lieutenant Jerimiah Gaffney was placed in charge of one group of soldiers. He had previous experience of the village, having been stationed there during the Civil War … He also held a long-standing grudge against a family named the Brosnans.[22]

On the evening of the sixth, Thomas Brosnan was taken by three men from the house of his grandmother. An hour later, his body was found by the roadside.[23]

The inquest heard how three men, one armed with a Peter-the-Painter and two with rifles, took Thomas from his grandmother’s house after which he was not seen alive again. The medical evidence was that he received three wounds in the back at the left side, three in front on the right side, and one on the left side. It was stated that one wound ‘must have been inflicted while deceased was lying face downwards.’[24]

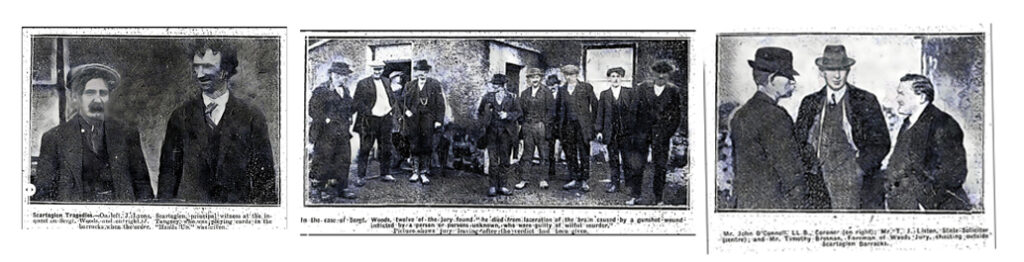

One theory about the murder of Thomas Brosnan was that on the night of the raid on the barracks, a game of cards was in progress in the guard quarters, and that Brosnan, known to play cards there, could identify them if he had been present.[25] However, 23-year-old Lieutenant Jeremiah Gaffney, described as a ‘Bashi-Bazouk,’ was later found guilty of the murder and hanged in Mountjoy Prison on 13 March 1924.[26]

Neighbours who knew Thomas Brosnan described him as ‘a quiet, inoffensive young chap who had never been identified with politics’ and whose whole attention was devoted to his father’s forge and shop.[27] However, unknown, it seems, to his father, Thomas was a member of Oglaigh na h-Eireann (IRA) and served as a Volunteer, 1st Battalion Kerry No 2 Brigade from 1918 to May 1923, being a Despatch Rider in 1920-21.[28]

An inquest into the deaths of James Woods and Thomas Brosnan was held in Scartaglin.[29] In the wake of the death of Thomas Brosnan, the Brosnan Fund was got up and the names of subscribers were published in the local press during January and February 1924.

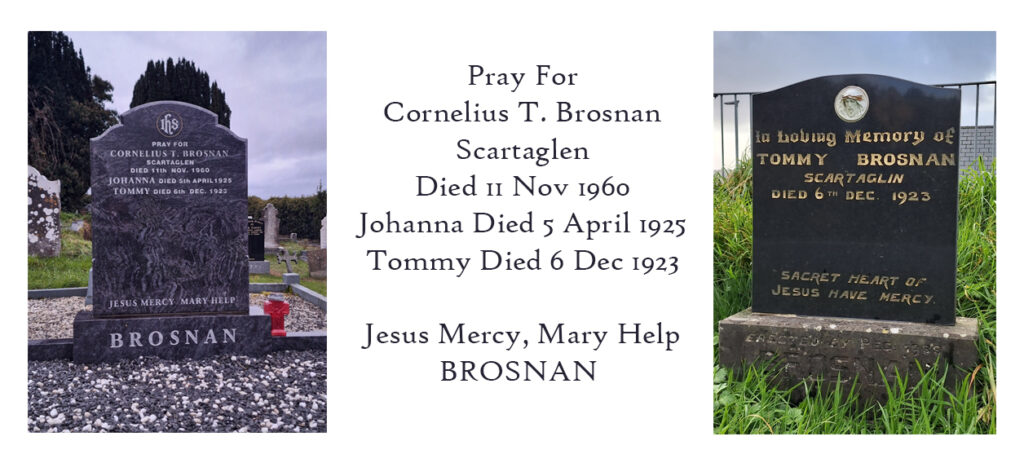

Thomas Brosnan was born in Scartaglin on 4 February 1903.to Cornelius T Brosnan, a blacksmith, and his wife Johanna, publican.[30] Johanna died on 6 December 1925, and Cornelius on 7 November 1960 at age 90.

Cornelius was laid to rest in Kilsarcon cemetery with his wife and his son.[31]

A TG4 documentary about the murder of Thomas Brosnan by Dingle filmmaker Aodh Ó Coileáin was produced for the series Ceart agus Cóir and screened in January 2010.

________________________________

[1] The Irish Civil War by Tim Pat Coogan and George Morrison (1998), p53. Reference courtesy Jeremiah Flynn. [2] The Atlas of the Irish Revolution (2017), p704. Reference courtesy Jeremiah Flynn. [3] The Fallen Gardaí Killed in Service 1922-49 (2017) by Colm Wallace, pp27-36. [4] ‘In Scartaglen they found themselves forced to use the house of local man Jerimiah Lyons as their temporary Garda station. The owner still occupied the house and it was clearly ill-equipped to serve as a police station as his family and the Gardaí living in the house were forced to share a kitchen’ (Wallace, The Fallen). [5] Colm Wallace (The Fallen) describes the attack as follows: ‘At around 8.30pm on Monday 3 December 1923, the makeshift station was raided by six armed and masked men. Five gardai were stationed there at the time; three were on patrol, and Guard Patrick Spillane and James Woods were present. Garda Patrick Spillane was forced upstairs and stripped of his uniform and clothes. Guard Woods, who had been in an adjoining room, was then sought and ordered up the stairs … The raider butted the sergeant with the rifle between the shoulder blades, in what appeared to be an attempt to force him to hurry his progress. At that point a blast of a rifle was heard. A bullet struck the sergeant in the back on the head and he fell forward on his knees on the ladder … Sergeant Woods was dead.’ [6] ‘Woods was just 22 years of age but O’Duffy’s policy was to appoint men with some form of higher education to senior positions’ (Wallace, The Fallen). A visibly emotional General O’Duffy condoled in person with ‘the sobbing father and invalid mother’ in ‘their awful bereavement’ (Liberator Tralee 22 December 1923). [7] In The Fallen, Colm Wallace identifies the townland of birth as Craggycorradan West. The townlands of Ballyryan and Craggycorradan West are both in the parish of Killilagh in Co Clare. [8] A copy of this booklet is held in the archive of Castleisland District Heritage, reference IE CDH 152. The Memorial Organising Committee was Chief Supt Donal J O’Sullivan, Tralee Station; Superintendent Michael Neill, Killarney Station; Sergeant Tim O’Leary, Listowel Station; Sergeant Michael Coote, Castleisland Station; Sergeant William Corcoran, Castleisland Station; Sergeant Kevin Dillon, Tralee Station; Sergeant Pat Doody, Caherciveen Station. Donal J O’Sullivan is the author of a two page article about Sgt Woods, ‘He Paid the Supreme Sacrifice,’ a copy of which is held in IE CDH 152. [9] Evening Herald, 12 December 1923. [10] Patrick Lyons, Knockreagh; John Kelly, Toornonagh, and Daniel Casey, Ballyhantouragh were held for twelve months in connection with the murder of Sergt Woods and Con Cronin, Ballyhantouragh for six months. All were released in January 1925 without charge. Michael Healy, Knocknagree, was charged with armed robbery but subsequently released. [11] A souvenir booklet issued at the time is held in the Castleisland archives, IE CDH 152. See also IE CDH 63 which contains references to Sgt Woods. [12] Report of occasion in Clare Champion, 21 May 2010. [13] An unpublished Memoir of James Woods by his nephew, Con Woods, is held in Castleisland District Heritage, Reference IE CDH 152. [14] Assistant Commissioner Thomas Woods joined the Garda in 1923 and was appointed Deputy Commissioner in 1955. A photograph of him on his appointment was published in the Irish Independent, 19 January 1955. Genealogy contained in A Last Walk Across The Fields, an unpublished memoir of James Woods by his nephew, Con Woods, held in Castleisland District Heritage, Reference IE CDH 152. [15] Unpublished memoir of James Woods by Con Woods, held in Castleisland District Heritage, Reference IE CDH 152. [16] Unpublished memoir of James Woods by Con Woods, held in Castleisland District Heritage, Reference IE CDH 152. Con remarks that ‘Ms. Bridget Lyons bandaged the large wound on his head, and she had the gruesome task of putting his brain back in his head.’ [17] Unpublished memoir by Con Woods held in IE CDH 152. ‘As Thomas was at this time a Superintendent of the Gardaí, he was armed with a revolver. When he drew his revolver, his traumatised mother intervened and said, “Stop, enough blood has been spilt”. At this point the gardaí accompanying the cortege intervened and said they would take control of the situation. They confronted the gang, overpowered them, hoisted the horse cart from the road and threw it over the hedge. The cortege was now able to continue its journey.’ An article about the shooting of Sgt Woods appears in the current issue of the Lyreacrompane & District Journal, Issue 14, November 2023. A talk, ‘The Murder of Sergeant James Woods in Scartaglin in December 1923’ by historian Owen O’Shea, was delivered in Killarney Library on Thursday 23 November 2023 at 7pm. [18] Garda Patrick J Spillane was stationed in Castleisland, Tralee, Ballybunion, Listowel and Drimoleague. He was posted to Skibbereen, Co Cork on 9 April 1935 where he served until his retirement on 15 May 1952. He married in 1934 and had three daughters and a son, retired Garda Pat Spillane, who joined the force in 1967. Garda Patrick J Spillane died at St Ann’s Hospital, Skibbereen on 12 December 1981. A photograph of him in 1972 holding a 1925 copy of Iris an Garda (Garda Review) was published in the Cork Examiner (14 July 1972). [19] Scartaglin police barracks, which was located near the entrance to the village close to where the garage stands today, was destroyed by fire on Tuesday 6 April 1920. It had been unoccupied for some days after an attack on it a few nights previous (Kerry People, 10 April 1920). A list of those involved in the attack on 31 March 1920 is held in Military Archives (https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/military-service-pensions-collection-1916-1923/1916-1923-resources/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Highlights%20OPs%201/Kerry/Scartaglin/A7%202%20Kerry%20Brigade%20pg%2012%20-%2013.pdf). A photograph of the burned building was published in Journal of Cumann Luachra No 5, 1989, p12. A former military barrack was brought from Dublin to Scartaglin and erected in October 1925. It was built of pine timber and sheet iron. It was demolished in 1977 (reference courtesy John Galvin, Scartaglin Parish News). [20] Freeman’s Journal, 11 December 1923. [21] It was stated that ‘there is a distinct connection between the murders of Woods and Brosnan and the raid on Mrs O’Connor’s house at Drumoulton where one of the occupants was wounded is the opinion generally held in the district’ (Evening Herald, 12 December 1923). ‘Following the tragedies of which Sergt Woods and Mr Brosnan were the victims, and also the serious wounding of the servant boy named Con Horan of Mullin, the people became terribly alarmed and fearsome for their safety, and m any of the residents of the district left their homes with the object of escaping any repetition of such awful deeds’ (Liberator Tralee, 15 December 1923). Turbulent Times Deeds of the Emerging State, an unpublished manuscript by Jeremiah B Flynn compiled in 2015, reviews events surrounding the wounding of Con Horan (1896-1978). [22] The Fallen Gardaí Killed in Service 1922-49 (2017) by Colm Wallace, pp27-36. [23] Freeman’s Journal, 8 December 1923. Further details from the report as follows: ‘The unknown men who took the young man away were three in number and were in disguise. They first called at his father’s public house and asked for his son. Mr Brosnan told them his son was down at his grandmother’s house. The men said they wanted him, and asked the father to show them the house. He accompanied them, and on his way saw his son chatting with a Civic Guard in another public house. The son was called out, and went with the unknown men back to his father’s public house where one of the strangers asked for whiskey. The publican had no whiskey, but offered to get some in another public house. The strangers said it would be all right, and asked the son to come with them, as they wanted to speak to him. He went with them. Nothing more was heard until an hour later when the father became suspicious at the non-return of his son. He went to the Civic Guard station and two of the Guards accompanied him with flash-lamps. On the public road which skirts the village, 600 yards from his father’s house, Tom Brosnan’s dead body was found, face downwards, with a bullet through his heart. At the inquest this evening, Cornelius Brosnan, blacksmith, father of the murdered boy, told the Coroner and jury how three men entered his wife’s public house about half-past six last evening, one having a Peter the Painter. His son, Tom, had worked with him at the forge up to six, and then went, as was his custom, to see his grandmother. About half-past six three men called to the house and asked for Tom. He told them Tom was at his grandmother’s house. The man, who was clean-shaven and had a Peter-the-Painter, asked the father to accompany them to Tom’s grandmother. The man with the Peter-the-Painter was near the light. Another man with a rifle was at the door, and the third man with another rifle was outside. Brosnan went out with the three men, found his son at his grandmother’s house and called him out. All returned to Brosnan’s house, where the man with the Peter-the-Painter asked for whiskey. Brosnan said he hadn’t any and offered to send Tom for some. The man with the Peter-the-Painter said: ‘It would be alright, that they wanted Tom up the road.’ Tom went with them towards the chapel and did not return. Becoming anxious he went to the Civic Guards and searched for his son. He went into a neighbour’s house and asked did they see any military around. Later, he saw the body of his son face downwards on the side of the road, at the Castleisland side of the chapel. He was then dead. He (witness) did not known any of the men who came to his house. The Coroner told Mr Brosnan he would be again examined at the adjourned inquest on Tuesday next when he could give any further evidence he was in possession of. Dr Wm Prendiville deposed that death was due to shock and internal haemorrhage caused by bullet wounds. From the nature of the wounds he believed the deceased died soon after being wounded. Replying to Supt Hannigan, the doctor could not say whether the wounds described were caused by revolver bullets or rifle bullets. The oblique wound must have been inflicted while deceased was lying face downwards. In reply to a juror, he said he could not distinguish between a wound caused by a rifle, a revolver, or a Peter-the-Painter.’ [24] Nenagh News, 8 December 1923. [25] Evening Herald, 12 December 1923. [26] ‘The band of soldiers associated with Gaffney did not act like soldiers at all but as if they were a body of Bashi-Bazouks’ (Belfast Newsletter, 21 February 1924). The following from the Freeman’s Journal, 14 March 1924: ‘Ex-Lieut Jeremiah Gaffney was hanged at 8 o clock yesterday morning at Mountjoy Gaol for the murder of Thomas Brosnan at Scartaglin, Co Kerry, on December 6 last. Gaffney, it is officially learned, left a written confession in the prison. This was forwarded to the Minister for Home Affairs after the execution of the prisoner in accordance with his request. In this confession Gaffney admitted full responsibility for the crime, and laid emphasis on the fact that he threatened to shoot Denis Leen if the latter did not obey his orders to shoot young Brosnan. He added that Leen fired at Brosnan, wounding him, but that the shots did not seem to have much effect, and that he (Gaffney) then came up, saw Brosnan trying to escape over a low fence, and fired shots into his body, whereupon Brosnan fell mortally wounded. The confession ended with a statement that he gave orders very emphatically, and that Denis Leen, in order to save his own life, fired at Brosnan. The story told of the last moments of Lieut Gaffney was that he was quite resigned to the fate he was to meet. From the beginning of his incarceration he was attended by Father MacMahon and Father Finlay. At no time did he show any signs of fear, and as a warder remarked before the inquest, ‘he died a splendid and a courageous death.’ On Wednesday he was visited by his father, to whom he spoke quite cheery words, assuring him that all was well with him; he was quite prepared to die, and felt sure of Heaven. ‘I wish to God,’ he told his father, ‘that everyone was as sure of heaven as I am. Tell mother that, and all my friends too.’ He bid goodbye to the prison officials before going to the scaffold, where he was attended to the last by the clergymen already referred to. For some time before that hour a small crowd of people congregated and held watch outside the prison gates. Most of them were women of the humble class, but as far as could be ascertained, no relatives of Gaffney were present. The women took their stand on the footpath a few yards from the gaol entrance, which they eyed eagerly as they held their beads, reciting aloud the decades of the Rosary. Nearing the fatal hour the door of the prison opened to admit a warder. A young girl, with tears in her eyes, dashed towards the doorway in the hope of getting in, but she was turned back by an official. A group of sympathisers dropped to their knees, and four or five of the women commenced to wail. Presently the heavy gaol door swung open and two warders came forth to post up, in accordance with the usual custom, the stereotyped notice announcing that the judgment of death had been duly carried out. The message, the ink on which was not yet dry, was posted high up on the prison door. The crowd stared at it for a while and then scattered, one woman angrily exclaiming that the ‘law had not been carried out.’ The notice was signed by Mr Redmond Roche, Sheriff of the County Kerry, and Mr Archer French Falkiner, Governor of Mountjoy, as witnesses of the execution. As on previous occasions, nobody other than those required by law was allowed to be present at the execution. It is stated that the executioner was Pierrepoint, the Englishman, who had been engaged by the government for the purpose. Yesterday morning at 11.30, the Deputy-Coroner, Dr Oswald J Murphy, held an inquest on the body of Lieutenant Gaffney. Dr Hackett, Medical Officer of Mountjoy Prison, gave evidence of being present at the execution at 8 o’clock. He examined the body immediately after the execution and found that death had been instantaneous and was due to fracture of the cervical vertebrae. The jury found that Lt Gaffney died in Mountjoy Prison on the 13th inst, the sentence of death being carried out in the execution of justice.’ It was stated at the trial of Lieutenant Gaffney that he had been living with the wife of Brosnan’s cousin, regardless of the protests of all the relatives of the woman’s husband. Evidence was also given alleging that the woman had attempted to poison the well from which the murdered youth’s family took water for domestic purposes (The People, 13 January 1924). An account of his involvement with Lena Keane is given in ‘The Murder of Tommy Brosnan, Scartaglin, 1923’ by Batt Brosnan Sliabh Luachra, Journal of Cumann Luachra, pp7-9. It includes an image of Sgt Gaffney. In 1925, Mrs Bridget Lyons, sister of Cornelius T Brosnan, was summoned for threatening language against a member of the Keane family ‘whose name was mentioned in connection with Gaffney.’ In cross examination, Mrs Lyons mentioned that as well as losing her nephew, she had a brother ‘killed by the Tans’ and stated that ‘ever since then these people were laughing and jeering at her and her brother, the father of the murdered boy’ (Liberator Tralee, 25 July 1925). [27] Evening Herald, 12 December 1923. [28] Cornelius T Brosnan claimed in an application for a military pension that he was not aware that his son was a member of Oglaigh na h-Eireann (IRA). ‘His death was not believed to be related to his military connection, but more because of Lieut Gaffney’s personal involvement with his family’ … ‘Deceased may be said to have entirely ceased being a Volunteer at the date of his death. There was no misconduct on the part of deceased that would have led to his being shot as far as I know and the evidence at the time showed … The applicant [Cornelius] did not know that deceased was in the Volunteers in 1922-23, that is, at the time of his death’ Ref: http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/docs/files//PDF_Pensions/R6/DP836%20Thomas%20Brosnan/2RB656%20Thomas%20Brosnan.pdf [29] District Coroner John O’Connell; T J Liston, State Solicitor; General Superintendent Hannigan represented the Civic Guards. Jury: Timothy Brosnan (foreman), Bryan O’Connor, John Gallivan, Dan Buckley, P Culhane, Jeremiah Sullivan. Michael Sullivan, John Collins, Pat Nolan, Pat Connor, Pat Shine, John Kerin, William Browne, Michael Kearney, Jeremiah O’Connor, Edward McSweeney, John Kearney and Ty O’Sullivan. At the inquest of Thomas Brosnan, Colonel McGuinness and Captain Cummins APM represented the military authorities. The verdict of the inquest on Thomas Brosnan was that he was shot dead on December 6 ‘by members of the National Army.’ [30] Cornelius T Brosnan was married in Castleisland to Johanna O’Leary, widow, daughter of farmer John Brosnan on 28 October 1902. The census of Ireland 1901 shows 40-year-old Johanna, licenced publican of Scartaglen, with her daughter Bridget O’Leary, age 14. Bridget, daughter of shopkeeper Michael O’Leary of Scartaglin, was born in Scartaglin on 12 February 1889. [31] Thanks extended to Martine Brennan for identifying the burial place of the Brosnan family, and for genealogical research. [32] The memorial, erected about 25 years ago, replaced an earlier Wooden Cross which was probably erected by Cornelius T Brosnan. The memorial, which was removed temporarily during the construction of the road on the nearby estate and replaced a small distance from its original site, is inscribed: In Loving Memory of/Tommy Brosnan/Scartaglin/Died 6th Dec. 1923/Sacret Heart of/Jesus Have Mercy. The base of the memorial, of different construct, is inscribed: Erected by Peg 1988/BROSNAN. Peg was Peg Lyons, first cousin of Thomas Brosnan. She died on 3 June 2001 aged 86 years and was laid to rest in Kilsarcon cemetery.