‘Was it not the fact that the evicted tenant and the caretaker were on extremely bad terms, the tenant having on one occasion struck the caretaker on the face?’ – Arthur Smith-Barry, 1st Baron Barrymore, House of Commons, 1894[1]

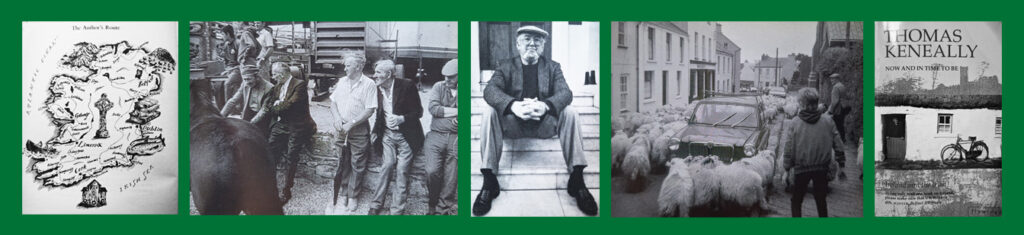

Castleisland District Heritage has acquired a copy of the travelogue, Now and in Time to Be by Booker Prize winner Thomas Keneally. It carries a rich historical subtext which makes for an entertaining and educational jaunt around Ireland a little over thirty years ago.[2]

Beneath the layers of academia, however, is the Australian author’s desire to connect, at some level, with his Irish roots. As he puts it, ‘We people of the diaspora, whether from Australia or Michigan or the plains of Canada, get back here, returning ghosts, utterly confused and in need of guidance’ – seeking a place ‘never but always known.’[3]

As the reader absorbs such things as the inherited habits of Penal days, the background of Ballymaloe House or observations on bowling on country roads, it becomes clear that Ireland’s tragic past weighs heavily on the author:

I’d never been able to come to Ireland without feeling that it was haunted by absences. Every little stone enclosure, and every cottage whose roof tree had been broken, spoke to me of evictions and forced emigration.[4]

In the course of Thomas Keneally’s pilgrimage-of-sorts, the reader begins to piece together his Irish roots. His great great grandfather, Daniel Keneally, was buried in Clonfert Cemetery at West End, Newmarket, Co Cork in the year 1844. Daniel’s son, Jeremiah, married Anne MacSwiney who was, according to family lore, related to the Mayor of Cork. Jeremiah and Anne produced a large family, perhaps thirteen children, who all emigrated.

Among them was Timothy Thomas Keneally (1859-1933), Thomas Keneally’s grandfather, who went to Australia and worked for a transport company until he applied for the licence of the Pelican Island Hotel – later renamed The Harp of Erin – in New South Wales. In 1892, Timothy sent a family photograph home to his father Jeremiah, who wrote, ‘You appear thin but apparently in good health.’ Timothy’s ‘amiable wife’ was pronounced ‘far in excellence as could scarcely be seen’:

What would I give if I could only gaze on your lovely wife and child for one moment … I fear an eternal decree that during my life I shall never again see you or any of my exiled children.[5]

Timothy had been granted the hotel licence on condition that he marry which he did, in 1889, to Co Clare native Kate McKenna.[6] Nine children were born to them. The youngest, Edmund Thomas Keneally (father of Thomas Keneally) was born in Kempsey in 1907 and nicknamed ‘Harper’ after the pub. Edmund married Elsie Margaret Coyle, a girl from New South Wales but of Donegal descent.

Their son, author Thomas (Michael) Keneally, was born in 1935 and the rest, as they say, is history.[7]

During his travels for Now and in Time to Be, Thomas Keneally included a trip to Newmarket, Co Cork which he had first visited in 1976. He did not disclose his full interest in the town, but offered a tantalizing hint:

I have another set of secrets. Here I only scratch the surface.[8]

One of those secrets came to light in February 2023 when Thomas Keneally visited the offices of Castleisland District Heritage.[9] He was back in Ireland in the course of research for a new book about the murder of James Donovan at Glenlara, near Newmarket, in 1894, for which crime John Twiss of Castleisland was hanged in 1895.

Donovan was caretaker of a farm from which a tenant named Keneally had been evicted, and Thomas Keneally disclosed that the tenant may have been one of his ancestors. This was problematic because – as Thomas Keneally put it – ‘Now that Twiss is out of the frame, Keneally is back in it.’

Unravelling

James Donovan, caretaker for the Cork Defence Union, had been placed in the Glenlara property, the former home of James Keneally, in about November or December 1893. Keneally, a father of eight, had been evicted on 4 October 1893.[10] Donovan, a widowed father of two young boys, was murdered on the night of 21 April 1894.

District Inspector Monson and several police set out for the townland of Glenlara, some five miles distant from Newmarket, and found that James Donovan, who had been caring an evicted farm for the Cork Defence Union, had been cruelly murdered. The scene of the crime is upon the Earl of Cork’s Estate. Two of his tenants were brothers, named John and James Kinnealy [sic] and they each held about 40 acres of land at Glenara [sic]. The country here is of a hilly and somewhat sterile nature and the brothers’ holdings adjoining each other they resided in one house … As might be expected the arrangement by which the caretaker was lodged in the same house with the evicted tenant led to unfriendliness between the parties, but the Kinnealys now state that the most cordial relations had existed between them and Donovan.[11] The hapless caretaker was beaten in the room he was in then dragged out into the yard and subjected to further ill-treatment of terrible severity. This assumption is clearly proven by the various pools of blood to be seen in the yard and the evident traces of a struggle which are abundantly apparent; but it is a remarkable if somewhat unaccountable fact that after all the frightful injuries which Donovan received, that he was still able to make his way back to bed and linger for hours before he succumbed.[12]

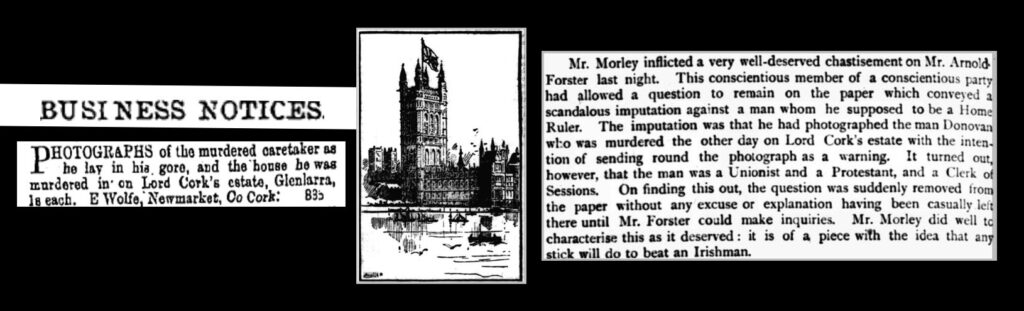

On 3 May 1894, questions were raised in the House of Commons about the adequacy of police protection afforded Donovan.[13] A photograph of his mutilated body was sold and circulated in Newmarket about which questions were also raised in government.[14] The photograph was evidently intended as a warning of the consequences of not obeying the rules of the Irish National Federation.[15]

James Keneally took up residence in an outhouse at Glenlara after the murder. Eugene O’Keeffe of Glenlara was tried for the crime in June 1894 and acquitted.[17] In August, James Keneally was prosecuted by his landlord, Lord Cork, for malicious damage and trespass at Glenlara.[18] It was gleaned from the proceedings that Keneally had continued on occasion to cut hay and graze the land at Glenlara, and had challenged the lawfulness of his eviction. It was also claimed that Keneally and Donovan had argued, and that Keneally had warned that ‘anyone that would go into that house he would have their life.’[19]

On 9 February 1895, John Twiss was executed for the murder of James Donovan.[20] In March 1895 a man named John Twomey was awarded £12 compensation for malicious injury to a horse at Glenlara. He had allowed a pedlar named Foley, who with his son had given evidence for the Crown, to stay at his house near the murder scene.[21]

One year after the hanging of John Twiss, at a wedding in Castleisland, there was a disturbance:

On Sunday last the daughter of a man who gave evidence against Twiss was wed to a farm labourer. As the bridal party left the church a mob followed hooting and crying ‘Down with the murderers of Twiss.’ Afterwards a number of men, dressed in fantastic garb, presented themselves outside the house where the festivities were proceeding, one of them bearing a rope round his neck and a card attached to it with the inscription ‘Remember Twiss.’[22]

John Twiss was Posthumously Pardoned by the Irish State on 16 December 2021 after a three-year campaign by Castleisland District Heritage. He is now, as Thomas Keneally states, out of the frame.

This year (2024) marks the 130th anniversary of the murder of James Donovan. Little can be said about Donovan’s life or the fate of his two sons. The case remains unsolved.[23]

___________________________

[1] In the House of Commons on 3 May 1894, Mr Smith-Barry asked, ‘Was it not the fact that the evicted tenant and the caretaker were on extremely bad terms, the tenant having on one occasion in the presence of the police or Mr Hanna [an official of the Cork Defence Union] struck the caretaker on the face’ (Belfast Newsletter, 4 May 1894). [2] Now and in Time to Be (1992) by Thomas Keneally. Collection Reference: IE CDH 208. [3] Ibid, pp3-4. [4] Ibid, p31. [5] Ibid, pp175-176. In April 1897, farmer Daniel T Keneally was found dead on the public road at Glenlara from ‘supposed’ heart failure. At the trial of John Twiss, James Keneally, son of Daniel T Keneally, stated that his father was first cousin of James T Keneally. [6] The marriage took place at Pelican Island. [7] Thomas is married to Judith and they have two daughters, Margaret and Jane. Judith has her own Irish tale. Her great grandfather, Hugh Larkin (or Lorcan) of Lawrencetown, Co Galway was transported in 1833 for Terryaltism. See Now and in Time to Be pp33-35. A photograph of Margaret Keneally with her father was published in a review of Now and in Time to Be in the Irish Independent, 30 November 1991. [8] Now and in Time to Be, p183. [9] Thomas Keneally kindly appeared at an event, ‘A Night with Thomas Keneally,’ organized by Castleisland District Heritage with moderator Frank Lewis at the River Island Hotel, Castleisland on 24 February 2023. He was accompanied by his wife Judith. [10] ‘The murdered man Donovan occupied an evicted farm upon the western rise of the glen at Glenlara, in the townland of Toureenmacormack three miles from the town of Newmarket, Co Cork … Twiss lived at Cordal, near Castleisland, Co Kerry some twenty miles from the scene of the tragedy … that he was innocent was and is the firm belief of the people in the neighbourhood of Newmarket’ (Irish Independent, 4 March 1905). Soon after the eviction, James T Kenneally appeared before the Kanturk Board of Guardians for relief, and stated that ‘he had been most unjustly evicted by his landlord, Lord Cork, as he got no facilities from that gentleman to enable him to make his rent. He could easily have paid his rent if he were allowed to take grazers but the landlord would not permit him to do so consequently he was unable to pay the rent and was evicted. The Board unanimously gave Kenneally, who has a wife and eight children, £1 per week relief for three weeks’ (Cork Daily Herald, 16 October 1893). [11] Evening Herald, 21 April 1894. [12] Cork Examiner, Monday 23 April 1894. [13] https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1804-05-03/debates/ef4050a0-732e-47d1-a155-62c6987e6be6/TheGlenlaraMurder [14] Local questions in Parliament May 1894. ‘Mr Arnold Forster to ask the Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland whether he is aware that the mutilated body of the dead man Donovan, recently murdered at Glenlara, Co Cork, was photographed, and that copies of the photograph are now being sold by a man named Wolff [E Wolfe] in Newmarket, and are being circulated in the neighbourhood as a warning of the consequences of not obeying the rules of the National Federation. Whether he has seen the photograph in question, and whether he can take any steps to stop the sale and circulation of the picture? (cheers). I would ask the right hon gentleman is he aware that this Wolff is clerk to the magistrate, a leading local Unionist, and that the people had no connection with him (nationalist cheers). Mr Morley: It is the fact. I am sorry to say that owing to some oversight on the part of the police who were in charge of the unfortunate man’s corpse that the person named in this question did take a photograph of it (hear, hear) and that the photograph was for a short time circulated. The police interfered and reprimanded and remonstrated with the gentleman who had taken the photographs, and I believe there is no more to be heard of it. It is quite true what the hon member says, that the gentleman who took the photograph was a petty sessions clerk, and as of the same religious and political faith as the hon member for West Belfast (loud cheers).’ Report in full, Cork Examiner, 11 May 1894. [15] In April 1894, James T Keneally of the Newmarket National Federation denounced the murder. ‘There was a good deal of agrarian agitation in the district, and James T Kenneally was prominently identified with same, being Secretary of the local branch of the Land League and National Federation. He was heavily in arrears with his rent and was evicted from his holding in October 1893’ (Kerryman, 27 April 1935). The Irish National Federation was formed in 1891: ‘A meeting of gentlemen interested in the formation of the Irish National Federation was held in Dublin yesterday afternoon. There were present Mr T Healy (presiding), Mr T D Sullivan, Mr Sheehy, and Mr Donald Sullivan. A statement was submitted for approval explanatory of the proposed constitution of the new body, and the proceedings were adjourned’ (Cork Examiner, 17 January 1891). ‘A political party established in 1891 by former members of the INL [Irish National League] who left the Irish Parliamentary Party when Charles Stewart Parnell refused to resign the party leadership as a result of his involvement in the divorce proceedings of Katharine O'Shea. It was led by Justin McCarthy until January 1896 (when he resigned); in February 1896 John Dillon became chairman of the INF. The party was dissolved in 1900 when the membership rejoined the Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond with Dillon as Deputy IPP leader’ (https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000830369). [16] ‘Throughout Saturday the police photographer was busily engaged in obtaining pictures of the deceased and of the locale of the crime’ (Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 28 April 1894). [17] ‘The man O’Keeffe charged with Twiss was acquitted. He is now in America’ (Irish Independent, 4 March 1905). [18] ‘James T Kenneally of Glenlara was summoned at the suit of the Right Hon the Earl of Cork and Orrery for wilful and malicious damage to complainant’s land at Glenlara and for wilful trespass. Mr H H Barry, solicitor, Kanturk, appeared for Lord Cork and Messrs N W Keller and P R Fitzgibbon solicitors represented the defendant. Thomas Davidson, examined by Mr Barry, stated that he was caretaker of the farm at Glenlara from which the defendant, Mr James T Kenneally, had been evicted. He found the defendant cutting a meadow on the lands, and on being asked to desist, he refused. He also saw Kenneally grazing his cattle on the lands on the 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th of the present month. Mr Hanna, of the Cork Defence Union, deposed that he was present when James T Kenneally was evicted on a habere. He got up possession from the sheriff’s representative on behalf of the landlord. Cross-examined by Mr Keller – John Kenneally’s name was included with James on the habere. He did not see John evicted at all. When James was evicted he went into John’s house. Mr Keller denied the legality of the eviction. John’s name had been included with James, and John had never been evicted. He contended that his client had a perfect right to act as he had done. Mr Barry – A more anomalous piece of impudence I have never heard of. Kenneally was legally evicted and possession of the lands taken under this habere. Mr Keller – John Kenneally’s house is on the lands of Glenlara, and we have it clearly that he never was evicted; therefore the present proceedings must lapse, as my client, James, was never legally put out of possession. Mr Langford said he would adjourn the case for a fortnight. His own mind was pretty clearly made up on the matter; but still he would not take it upon himself to decide the point until he would have the assistance of Major Hutchinson RM who would probably be present on the next day. Mr Barry said that, in the meantime, Kenneally should give an undertaking not to interfere with the place. Mr James T Kenneally – I will give no such undertaking; and I have a perfect right to do what I wish there’ (Cork Examiner, 27 August 1894). ‘Newmarket Petty Sessions before Major Hutchinson RM and Mr A Langford. An Evicted Tenant sent for Trial. James T Kenneally, an evicted tenant on the estate of the Right Hon the Earl of Cork and Orrery was prosecuted at the suit of his Lordship for wilful damage and trespass on his property at Glenlara. Mr H H Barry, Solr, prosecuted and Mr N W Keller, solr, Kanturk, and P R Fitzgibbon, solr, Newmarket, defended. Mr Barry said that the present case was on the last court day but that Mr Langford, who sat alone on that occasions, wished that the case should wait for his worship Major Hutchinson. The case appeared to him (Mr Barry) to be one of extreme simplicity. Kenneally was a tenant of Lord Cork’s on portion of the lands of Glenlara. Out of that land he was evicted on the 4th of October 1893. Since then he had the impudence to come on the lands, cut the hay, and though warned not to do it, persisted in grazing and trespassing on the lands. Mr Hanna, of the Cork Defence Union, examined by Mr Barry, stated that he took up possession on behalf of the landlord at the eviction in October 1893. Possession was taken under a writ of habere bearing the sheriff’s return that it had been duly executed. A caretaker named Keating was placed there, and he was succeeded by Donovan who had since been murdered. The present caretaker of the farm was Thomas Davidson; on the 7th of July he found Kenneally cutting hay on the farm. He (Mr Hanna) cautioned him that if he would not desist he would be prosecuted; Kenneally replied, and said he would cut and save it, and carry it away in defiance of Lord Cork or his subordinates. Mr Keller – This writ, under which these proceedings were taken, was obtained in 1889, five years ago? Yes. Mr Keller – Do you know that since that writ was obtained that money was received from Kenneally as rent? I believe so. Mr Keller here produced a receipt for rent paid by Kenneally since the writ was obtained. Mr Keller – Did you know the lands before the eviction? No. Mr Keller – You simply took what the sheriff’s man gave you? Yes. Cross-examination continued … When he went on the lands on the 7th July he found Kenneally in the occupation of an outhouse. He could not say how long he had been living there. Re-examined by Mr Barry – He was certain that on the day of the eviction he got up possession of the house in which he saw Kenneally on the 7th July. Thomas Davidson deposed to the various dates on which he found Kenneally’s cattle trespassing on the lands. For the defence it was contended that Kenneally was never legally evicted, and the house on the lands in which he was living at present was never evicted at all. Evidence was called to show that the house was locked at the time of the eviction and that it contained milk and potatoes. Andrew Spannin, sheriff’s bailiff, on being examined, stated that he looked into the house in question when proceeding with the eviction, and that it contained nothing. He also gave possession of that house to Mr Hanna. Mr Keller said that they could not hold that Kenneally cutting the hay on the farm, which was ripe and fit to cut, was inflicting wilful damage to the land. Mr Fitzgibbon – The fact of the matter is, the farm would not be worth the bit of hay he took off it, only for the labour and industry of Kenneally, and his father before him. For the damage to the land Kenneally was fined 20s, and 5s costs, and for the trespass the cumulative fines amounted to £1 14s and costs in each case’ (Cork Examiner, 10 September 1894). ‘Newmarket Petty Sessions. Mr James T Kenneally of Glenlara who was evicted from his farm last year at the instance of Lord Cork, has elected to go to prison rather than pay the fine imposed on him for trespass committed on his evicted farm. Mr Kenneally has written to me to state that he is willing to leave the arbitration of the dispute between him and his landlord to two police officers, viz, District Inspector Monson, Newmarket and District Inspector Irwin of Listowel’ (Cork Examiner, 24 September 1894). At the Mallow Quarter Sessions of November 1894, ‘in the case in which James T Keneally of Glenlara near Newmarket was charged with having taken forcible possession of a farm from which he had been evicted, Mr H H Barry, solr, on behalf of the landlord, applied to have a bill sent up to the Grand Jury against Keneally. His Honor granted the application, and explained the law on the subject. After some consideration the Grand Jury found ‘no bill’.’ (Cork Examiner, 12 November 1894). [19] ‘There was another charge against Kenneally for taking forcible possession of an outhouse on the lands from which he had been evicted. Thomas Davidson deposed that on the 3rd inst he went to Kenneally and requested him to leave the house and give up peaceable possession. He put his hand on Kenneally’s shoulder, but Kenneally refused to go. Constable Francis Kiernan deposed that at the time of the eviction Kenneally and his family went to live with his brother John some time in May. After Donovan, the caretaker, was killed he went to live in the present house. Mr Fitzgibbon – Before Donovan was killed did you not hear Kenneally assert his right to this house? Witness – I heard Donovan and himself arguing about it. Donovan claimed the house, and Kenneally said it was his, as the eviction was quite illegal, and that anyone that would go into that house he would have their life, or words to that effect. Kenneally was returned for trial to the Mallow Criminal Sessions. Bail was accepted, himself in £100 and two sureties of £50 each’ (Cork Examiner, 10 September 1894). James T Kenneally was prosecuted for assaulting a woman named Mrs Manley with a stick at Newmarket on 15th August 1899, striking her violently on the head. Details of case in ‘Assault on a Woman,’ Cork Examiner, 4 September 1899. [20] His remarkable speech from the dock vindicates and may be interpreted as an able defence: http://www.odonohoearchive.com/death-before-dishonour-john-twisss-speech-from-the-dock/ [21] Cork Examiner, 15 March 1895. [22] Munster Express, 22 February 1896. [23] In ‘I forgive them all’: The Judgement of John Twiss (2007) by Newmarket native, Paudy Scully, a blind woman named Nanny Keeffe with ‘strange supernatural powers’ has a vision in which she sees ‘James Donovan floating in a coffin full of blood.’