On Fair Day, 8 September 1884, Earl Spencer, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and his suite passed through Castleisland during a week-long vice-regal visit to the South of Ireland. It was a Monday, and the weather was notably fine.

The visiting party included the Lord Lieutenant’s aides-de-camp, Captains Ross and Little, his private secretary, the Hon Captain Stopford (one report named him as Stafford), Captain the Hon Thomas Oliver Westenra Plunkett DRM, acting as avant-courier, H F Considine the Resident Magistrate, District Inspector Davis, and Captain Sunberry of the 11th Hussars, as well as an escort of hussars under command of Lieutenant Lumley, and an escort of police.[1]

The cavalcade was the embodiment of the authority that had, the previous year, refused an appeal for clemency in the case of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett. The people of Castleisland, and beyond, had hardly forgotten. Indeed, one writer asked what was the object of Earl Spencer ‘careering around Kerry on his galloping horse’ if not in ‘deliberate and impudent defiance of Irish public opinion,’ and coming at the very moment ‘the most horrible proofs of guilt are accumulating against his administration’ and when ‘the dying cries of innocence of Poff and Barrett are still borne upon every breeze’:

Not to behold the scenery, for Millstreet and Castleisland are not paradises lapt in arbutus groves, but dreary, stricken villages remarkable for nothing more than for the grinding oppression that plagues them and perhaps the fierce and stubborn front they have shown to their oppressors.[2]

The entourage had departed from Lord Kenmare’s mansion in Killarney en route to Listowel via Castleisland early that morning. The Lord Lieutenant, who travelled on horseback, made a few stops on the way, including Lisheenbawn, scene of the assassination of magistrate Arthur Edward Herbert in 1882. The exact place was pointed out to him, ‘particularly the elm-tree where the men lay ambushed and the spot where the unfortunate magistrate fell.’

The party moved on to the temporary soldiers’ barracks about a mile outside the town which was draped with flags and displayed elaborate decorations from the roof, streamers flying from chimneys. There the Lord Lieutenant was received with ‘customary military salute’ and lunched with a company of the 2nd Queen’s.

The vice-regal cavalcade proceeded to Castleisland where from the summit of the hill which crowned the entrance to the town ‘the first thing his Excellency could perceive was the many flags – all pure emblems of loyalty and devotion – gracing the top of the constabulary barracks.’[3]

However, as the party entered the town, the Lord Lieutenant was greeted by a black flag displayed by Mrs Poff, widow of Sylvester, bearing the words ‘Murder / Remember Poff and Barrett.’ The ominous symbol floated in the breeze as the crowd raised a cheer for Parnell and Davitt before lapsing into passive silence as the Lord Lieutenant passed by. The police attempted to tear down the banner but it was suddenly withdrawn and the door of the house closed.

As the party continued to the new Catholic Church under construction, nowhere was an attempt at a cheer or demonstration of welcome made, the message of the Irish people was conveyed loudly by silence. There was a hostile reception at Pound Lane where parties there carried belligerent signs ‘so far that the Hussars drew their swords.’[4]

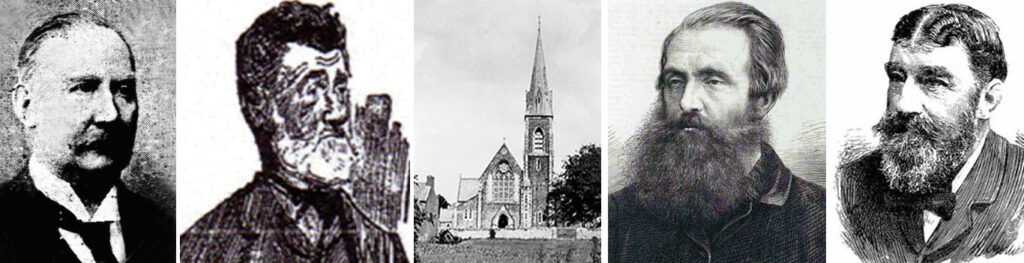

The Lord Lieutenant made a short visit to Archdeacon O’Connell’s residence and to the nuns of the convent. After leaving the convent, he entered the new church by the side door accompanied by his aide-de-camp, private secretary, Hon Captain Stopford, H F Considine, District Inspector Davis, Captain Plunkett and Captain Sunberry.

The Lord Lieutenant surveyed the interior of the building and admired the architecture while Rev J O’Leary, Parish Priest of Ballymacelligott, performed on the organ. It was at this point that Mr P D Kenny, Chairman of the Tralee Board of Guardians, was observed ‘reclining on a seat close at hand,’ and was called upon for introduction to the Lord Lieutenant. The exchange was reported as follows:

Capt Plunkett – This is Mr Kenny, Vice-Chairman of the Tralee Board of Guardians. His Excellency – I am proud of your acquaintance. What is the state of this locality in general as regards its crops? Mr Kenny – The potato crop is fair, but there is a large falling off in the hay. The corn crops are not at all up to the average of the past years, and farm produce is very depressed, for example, there is a falling off of 30 per cent in every description of cattle from last year’s prices. His Excellency – I have noticed a reporter present. Reporter – Your Excellency, I am taking notes, not of private matters but public.[5]

The interaction, spontaneous, and short, might have ended there. Unfortunately for Mr P D Kenny however, it was regarded as nothing short of fraternising with the enemy, and his good name would be seriously compromised in that moment.

Patrick D Kenny

Patrick D Kenny, a farmer, was the first man from south Kerry to be imprisoned, on 11 March 1881, under the Coercion Act for his role as President of the Castleisland Land League.[6]

He had been arrested ‘on reasonable suspicion of his inciting people to take up arms.’ An ‘Indignation Meeting’ or protest was held in Castleisland two days after the arrest to protest at his apprehension and that of assistant secretary of the league, T O’Connor Brosnan.

A very bitter feeling was evoked through this country where Mr Kenny has the reputation of being a sterling, intelligent, honest type of the class whose claims he advocated with fearlessness has cost him his liberty. As president of the local league here he has endeared himself to its members as much by the affable dignity with which he conducted the business at its meetings as by the assiduity and determination with which he attended to the duties of what was fast becoming a post of danger.[7]

In August 1881, during his incarceration, 100 horses and 200 men and women were engaged in saving the turf of P D Kenny, ‘though the distance from the bog to the farmyard was three miles, the work of several days was accomplished in a few hours.’[8]

P D Kenny was released from Kilmainham on 6 September 1881. His return to Castleisland was greeted by a great demonstration of some three thousand people, an occasion ‘which will not soon be forgotten.’[9]

Among those who met him at Gortatlea train station before he steamed on to Castleisland were Rev John Griffin CC, Tralee and his brother-in-law, Rev A Murphy CC, Ardfert, formerly of Castleisland parish. On emerging from the train in Castleisland, Kenny was raised on the shoulders of the people to inspiring music from brass and fife and drum bands and chaired through the main street to the Land League Rooms, the procession ‘a moving grove whose foliage was variegated by banners, bannerets and portraits of heroes and martyrs.’

He addressed the crowd from the window of the league rooms:

My friends I most heartily thank you for the warm and kind reception you have given me on coming back to labour once more with you in the good old cause. For six months now, I have been in the company of noble and brave men, shut in with them from the light of freedom but it has not in any way lessened my ardour in the cause for which I was imprisoned and I come as determined or more determined than ever to work with you until landlordism is no more. I have to call a cheer for the Land League, and for another, and a greater cheer, for those good ladies who ministered to our wants and provided our comforts inside, the ladies of the league. I would ask you after the other gentlemen have addressed you to go to your homes peaceably as a further favour and compliment to me.[10]

P D Kenny’s career in local affairs was sketched by the late Michael O’Donohoe, who noted that P D Kenny leased a farm at Ballymacadam from landlord, Markham Leeson Marshall, in 1854:

Kenny was a very successful farmer and is on record as having won prizes with his shorthorn calves at Kerry Agricultural Shows. The exact location of the farm is shown by the stone pillars and iron gates he erected which are still there today. From 1878 to 1885 inclusive P D Kenny was returned the PLG for Crinny. Prior to 1883 the chairmanship of the Union was dominated by the Establishment but their reign came to an end in that year when a nationalist was elected chairman. P D Kenny was elected vice chairman. They both retained their positions in 1884. In the fall of 1885, the Castleisland House League was formed. It was obviously based on the perceived success of the Land League in gaining rent reductions. P D Kenny attended at least one of the meetings and proceedings were reported in the Sentinel. At a meeting of the league in August 1886 the list of tenants and landlords who had received and made abatements since the league was started was revealed. It is known that not all landlords were in favour of giving reductions. A local blacksmith refused to shoe the horses of one such landlord. Presumably the list was published to acknowledge the generosity of those who had given reductions and to put pressure on those who were not complying. We see from the list that Pat Kenny gave reductions in two instances. A comparison with the other figures shows that the properties were of a reasonably substantial nature. Of course it is not a certainty that the man in question was P D Kenny though it is most likely. The last reported meeting of the league was in January 1887. In 1886, he resigned as representative for Crinny and instead unsuccessfully contested Castleisland. He then disappeared for a few years but, in 1890, 1891 and 1892, he was returned to represent Kilmurry. He was a regular attendee at meetings and a ready contributor to debates. He strongly supported the claims of Castleisland people – especially the families of ‘suspects’ who sought relief. On one occasion he was surcharged £2. During his time, a fever hospital was opened in Castleisland, a new church was built (he in fact seconded the motion to do so), and a new sewerage scheme and water supply were introduced. He was a member of almost every committee in the Castleisland area. Flapper races were common at the time but in November 1886, steeplechases were held under the rules of the Irish National Hunt Steeplechase. P D Kenny was on the committee.[11]

By the time of the Lord Lieutenant’s fateful visit, Mr Kenny was experiencing some form of fall from grace. A whisper of dissent came from an anonymous writer to the Kerry Evening Post in March 1884 who asked why, when visiting sites for cottages in the Castleisland electoral division with civil engineer, Mr Keane, Mr Kenny gave no site on his own farm, ‘although it is an extensive one and having no labourer living on it.’[12]

And in the year after the Lord Lieutenant’s visit, John J Greaney of Meenleitrim was attacked by two men for opposing P D Kenny in the coming election of Guardians, a report of which stated, ‘It appears Mr Kenny has not yet got over the indelible disgrace of having shaken hands with the Lord Lieutenant on the occasion of his late visit to Castleisland.’

The handshake, which Mr Kenny denied came from him but was unwittingly accepted by him, resulted in his censure by the league.[13] Mr Kenny tried to set the record straight soon after the event by explaining the circumstances publicly in a letter to the editor of the Kerry Sentinel. Writing from Ballymacadam on 23 September, his account showed how he was put in a very uncomfortable situation without warning which, in the highly charged temper of the times, cast a finger of suspicion on him:

As I am the party referred to as being introduced by Captain Plunkett to the Lord Lieutenant on the 8th inst, it is my duty to lay the facts as shortly as I can before you. The 8th inst being fair day in Castleisland, I was talking to a friend of mine about 1 o’clock pm when a number of horse-soldiers &c, passed by some distance from where we stood. My friend said, ‘Come and see what will come of this,’ and without purpose or meaning or using the precaution which I ought, I went into the new church, where there was a number of people. After a lapse of a few minutes, the Lord Lieutenant entered the building when, to my surprise, he and Mr Considine went up to where I was.

He made it quite clear that it was Mr Considine, and not Captain Plunkett, as reported, who introduced him, stressing that he ‘never knew anything of Captain Plunkett except what I read of him in the press.’

His letter went on to explain, to the obvious question that was being asked, how he was acquainted with Mr Considine.

On the 7th March 1882, at a very early hour in the morning, a Mr Taylor, S.I. who was then stationed in Castleisland, with a number of police came to my house and said he wanted to search it. In the course of a close search, including the reading of my private and other correspondence, I found about one ounce of powder and two or three of small shot, which I at once handed to one of the police, it being there for years unknown to me, as I had no gun. Immediately after this very great crime I was summoned in due course and fined in a smart sum which I had to pay with costs on the spot. Mr Considine, RM, occupied the chair on this occasion – hence his knowledge of me.

He referred to his treatment in Kilmainham Prison, and the refusal of the Castle authorities to allow him home even under police guard to attend the funeral of his brother, to whom he was very close, who died on 28 March 1881 soon after discovering his brother’s incarceration. ‘I state these facts to show that I owed the representatives of English law in Ireland no favours, and not for the mere purpose of recalling to the public mind the inconvenience I suffered with hundreds of others through absence from home and family for several months.’

He vehemently denied being the recipient of any benefits ‘nor the anxious expectant of future favours,’ and hoped for a calmer consideration of ‘the supposed mistake’ made and restoration of ‘the undisturbed co-operation in National matters that has ever existed’ between him and the league.

I firmly hope that the members of the Castleisland National League while asserting a principle in requiring me to retire from the presidential chair, do not still believe me capable of having forgotten – in a moment – lifelong principles and associations. A consciousness of the rectitude of my conduct will enable me to wait patiently.[14]

In the times that prevailed, there seemed little hope of restoring Mr Kenny’s good name in a community scarred, suspicious, and screaming for vengeance in the wake of the hangings of Poff and Barrett. The episode would enter the lore of the people:

My name is Patrick Kenny, I’ll never deny the same, And near Castleisland I reside, that ancient place of fame. Among my friends and neighbours I lived in high renown, Till Earl Spencer came one day scavenging through the town. I did not go to speak to him, twas he that spoke to me, He passed me many compliments, his talk was frank and free. But though his speech was quite polite and all his smiles were bland, Twas wrong I know to meet him so, and shake his gory hand. Tis well I remember – the moment that he spoke, The honest men he doomed to death, the gallant hearts he broke, The wicked crew he paid and hired to keep our land in thrall, But yet by some unlucky chance I quite forgot it all. The members of the Land League, they tried me for the crime, And from the post of Chairman dismissed me for a time. But soon I hope they’ll pardon me, for well they ought to know, I fought and suffered for the cause not very long ago. I’ll take a trip in Dingle Bay, a Turkish bath in Cork, I’ll air myself some windy day upon the Top of Torc. I’ll purify myself once more, and penance I will do, So don’t reject a comrade that still is loyal and true.[15]

Patrick D Kenny died on 6 June 1902. The event seems to have passed unnoticed in the press, though it may have been overshadowed by the death of nationalist, Edward Harrington, of the Kerry Sentinel.[16]

In March 1924, his son, John Patrick Kenny, father of Volunteer Patrick Kenny, instructed Maurice T Prendiville in the auction of the farm, dwelling house and out-offices of Ballymacadam.[17] This is the last we hear of John Patrick Kenny.[18] Local lore has it he disappeared from the district, and was rumoured to have met an unfortunate end.[19]

Conclusion

P D Kenny might be regarded today as an unfortunate man who forfeited his place in the affections of the community in a manner of small ways not known beyond rumour, sealed with his historic encounter in the new church of St Stephen and St John, the building of which he had, ironically, seconded. He tried to assuage the 1884 affair publicly by letter, and was prepared to ‘wait patiently’ for forgiveness. He was intelligent enough to know, however, that his life could never be the same.

The community stood together in its protest against the hangings of Poff and Barrett, two innocent men who found no voice in the face of an establishment Kenny had met, however inadvertently, with his very hand. The large number of people assembled on Fair Day in 1884 stood silent; a few, on the outskirts, booed. The people of Pound Lane caused sufficient concern for the authorities to draw their swords. The heartbroken Mrs Sylvester Poff took a black flag with the words Murder and Remember Poff and Barrett painted either side of it, which she bravely displayed in the very face of a daunting military procession just as it entered the town.

There was simply no room for handshake of any kind.

There might, today, be a measure of understanding, and perhaps, of pardon for the actions of P D Kenny. It will be made easier however, with official pardons for the innocent Sylvester Poff and James Barrett.[20]

__________________________

Comment by John Roche, Chairman of Castleisland District Heritage

Does the good name of P D Kenny deserve a reprieve? What was his crime? He spontaneously accepted the proffered hand of a Pariah on a day when local resentment was in a state of justified rage. The Judicial Murders of Poff and Barrett was still a gaping wound.

P D Kenny was, until then, described everywhere as a highly respected local leader and community activist. As Land League President he had endured six months in Kilmainham jail, interned without trial for his part in the fight against evictions, nowhere more successful than in the Castleisland area, to the credit in a large part to P D Kenny and his followers.

The hated Earl Spencer was brought and introduced to Mr Kenny by a magistrate who knew Kenny because he had fined him in court some time previously. There was nobody present, other than the families of Poff and Barrett, with more reason than Kenny to refuse that handshake. Should he have refused?

As someone with seventy years’ experience of involvement in leadership at local, county and national level, it is my contention that he should not. Many years ago a wise man said to me, “The open palm in handshake is always more effective than the closed fist.”

He accepted the hand and proceeded to outline the difficulties experienced by the people he represented – the mark of a good leader. ‘Politics is the art of the possible.’

He graciously accepted the punishment meted out to him by the organisation he led, and humbly stated his case in writing publicly. He asked for pardon in time and there is no evidence that it was ever granted.

Castleisland District Heritage is seeking Presidential Pardons for John Twiss, Sylvester Poff and James Barrett, who were branded murderers by a corrupt regime. We are very hopeful of a positive outcome.

I think that on behalf of our ancestors, we should grant pardon to Patrick D Kenny, accept his bona-fides and restore his good name.

___________________

[1] Captain ‘Lumberg' was given in one report. [2] Flag of Ireland, 13 September 1884. [3] Cork Examiner, 9 September 1884. [4] Cork Examiner, 9 September 1884. [5] Kerry Evening Post, 10 September 1884. ‘The Lord Lieutenant, in his usual bland and courteous manner, turned the subject with a good humoured remark and a little bandinage was indulged in by Captain Plunkett at the expense of the reporter whose over zeal had got him into a difficulty.’ P D Kenny later stated that the name of Plunkett was reported in error, and that it was Mr Considine who made the introduction. The vice-regal party resumed its journey to Listowel where it received a similar reception, ‘people totally abstained from any display ... as his Excellency rode in, they preserved the most solemn silence. Not one word was uttered, at least not sufficiently loud to reach his ears, and amidst a surging crowd of silent peasants, the cavalcade rode on to Lord Listowel’s’ (Freeman’s Journal, 9 September 1884). The Lord Lieutenant left Gurteenard, Listowel, for Ardfert the following day, where he was received by William Talbot Crosbie, later visiting the new pier at Fenit, continuing towards Tralee, where they had refreshments at Seafield, at the invitation of Sir H Donovan. There followed ‘a frigid reception’ in Tralee, where a black flag was hoisted at the Young Men’s Reading Rooms, the motto similar to that painted on the one exhibited at Castleisland. ‘The police attempted to seize the flag but desisted on being brought to their feet by being told that they were not legally authorised to enter the house’ (Kerry Weekly Reporter, 13 September 1884). [6] Kenny said this himself in a letter to the editor of the Kerry Sentinel, 30 September 1884. It was also remarked on in another report of his imprisonment: ‘P D Kenny, president of the Castleisland branch of the Land League, was arrested under the Coercion Act on the 11th of March and was the first ‘suspect’ arrested under the Act in the Castleisland district’ (Irish Examiner, 7 September 1881). [7] Kerry Sentinel, 9 September 1881. [8] Irish Examiner, 4 August 1881. [9] Report of event, Kerry Sentinel, 9 September 1881. [10] Kerry Sentinel, 9 September 1881. [11] IE MOD/55/55.1.160. Mr Kenny provided a description of his farm and improvements he had made at the Tralee Land Session; see Kerry Sentinel, 5 February 1890. [12] Kerry Evening Post, 26 March 1884. [13] Kenny remarked on the handshake during his examination at the Times Commission in 1889. Asked if he had been expelled from the National League, he replied that he had not but that he had been censured. Questioned further about this, he replied (to laughter) that it was for shaking hands with Earl Spencer. ‘It was not me that shook hands with the Earl but the Earl who shook hands with me (renewed laughter)’ (Kerry Sentinel, 22 June 1889). On the same occasion, Kenny ‘distinctly swore that there was no connection whatever between either of the League and Moonlighting.’ [14] Kerry Sentinel, 30 September 1884. [15] The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0446, pp 217-218. Told by Con and 65-year-old Maurice Connor, Portduff, Castleisland. [16] Patrick D Kenny was married; the census of 1901 shows that in that year he was 75 years old and widowed, living at Ballymacadam with his two sons, John, age 28, and Michael, age 23, described as ‘an imbecile.’ A visitor was also present, Mary Kenny, age 40. Another son, Jeremiah, who worked as an accountant at the Munster Bank, Cork, died on 15 January 1880 after becoming unwell and falling from a window (account of death and funeral in IE MOD/55/55.1.160). [17] Patrick Kenny, Irish Volunteer, died in 1924, and is remembered at the Republican plot, Kilbannivane. Short biography in Dying for the Cause: Kerry’s Republican Dead (2015) by Tim Horgan, pp205-206. [18] In 1911, John Patrick Kenny was resident at Ballymacadam with his family, Co Clare born wife Margaret, practising Church of Ireland, and Limerick born mother-in-law, Anne Cooney, Roman Catholic (a family of Cooneys came to the area and lived as caretakers on an adjoining farm in c1890). Church of Ireland records show their children Elizabeth Lilian was born in 1904, St John Vincent in 1906, Jeremiah St G in 1907 and Annabelle in 1909. All were baptised in the Church of Ireland parish church of Ballymacelligott and Ballyseedy. In the Ardfert and Aghadoe Diocesan Board of Education Sunday School examinations of 1913, St John Kenny was 1st in lower infants, and in Division 1, Lillie Kenny and Eric Kenny were joint first with a number of others including the Anderson family. The last named, Eric Kenny, was eldest son, Patrick Gerald, born c1903, who served as a Volunteer in the Castleisland Company of the 7th Ballalion, Kerry No 1 Brigade. Annabelle Kenny emigrated to New York in 1929, and married in June 1940 to William Patrick Carmody and had issue including two sons, Brian and Brendan. Annabel Kenny Carmody died on 26 October 1987. My thanks to Marie Huxtable Wilson for genealogical research. [19] John Kenny was reputed to have disappeared in about 1924, and after the death of his son, Patrick Gerald Kenny (otherwise Eric Kenny) who died on 15 May 1924 and is remembered on the Kilbannivane Monument. The disappearance of John Kenny was a sensation at the time. Local lore had it that he was murdered in his own home and no remains or trace of his body was ever found, despite a police search over an extensive area with beagles. Nobody seemed to know why Kenny was killed but it was theorized that his body was boiled in an industrial farm type boiler (a metal implement of approx 40 gallons, common on bigger farms, used to boil potatoes and meal for livestock). One local theory was that the pot was searched for his teeth. Local lore has it a horse and rail or creel (a horse-drawn implement about 3.5 ft from the car up, a layered or laddered type of construction used for transporting pigs, sheep and small cattle to the market or factory) was seen coming from the Ballymacadam direction through the town and it was speculated that the remains were inside to be taken to the tide near Banna on pretext of drawing sand for building material. The Kenny farm was sold in about 1924 and purchased by a Herlihy family. [20] Castleisland District Heritage is currently preparing applications for the Presidential Pardons of Poff and Barrett.