And lo! As he spoke, there beside him, some shadowy beings appeared, And his heart’s blood grew cold as he saw them, though he scarce would confess what he feared. Then summoning courage, ‘Who are ye?’ he asked, in a quivering voice, And sternly one shadow made answer, ‘Behold me, your victim, Myles Joyce, Hither come as you asked to do honour – you doubtless remember the name Of the man whom, though dead, you still branded with the stigma of murderous shame. And others have hither come with me, Poff, Barrett, and several more, All forming a small deputation to speed you away from our shore. – From ‘The Red Earl’s Vision’ by Theodore Charles Christopher Hoste-Henley1

The innocence of Poff and Barrett in the murder of Thomas Browne of Dromultan on 3 October 1882 was proclaimed by so many, for so long, that the indignant voice of the past continues to this day.

No motive for the murder was ever assigned to the men and the miscarriage of justice against them was enshrined in the songs and ballads of the people..2

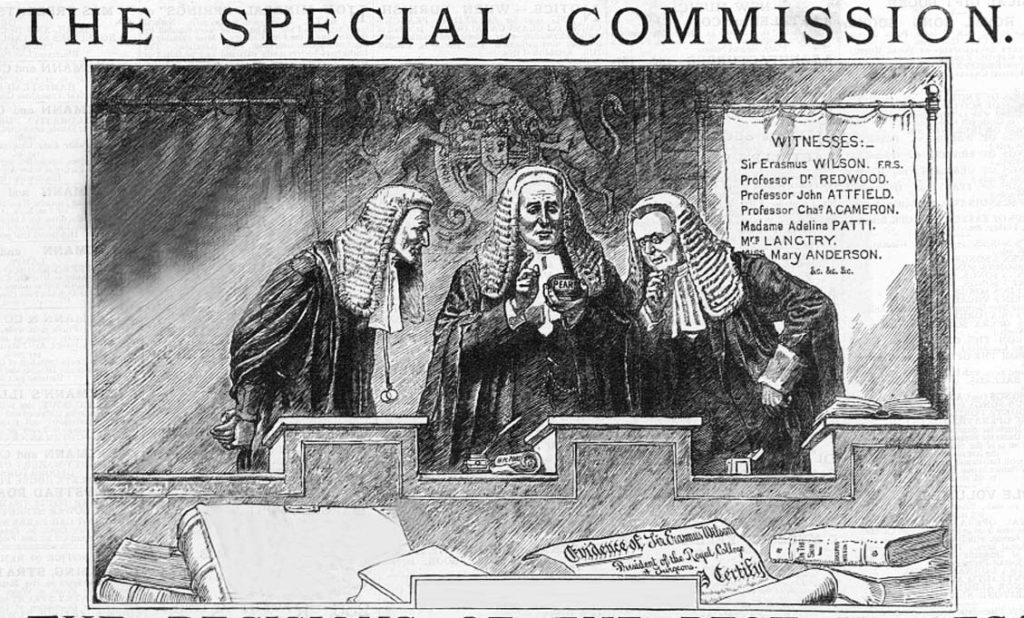

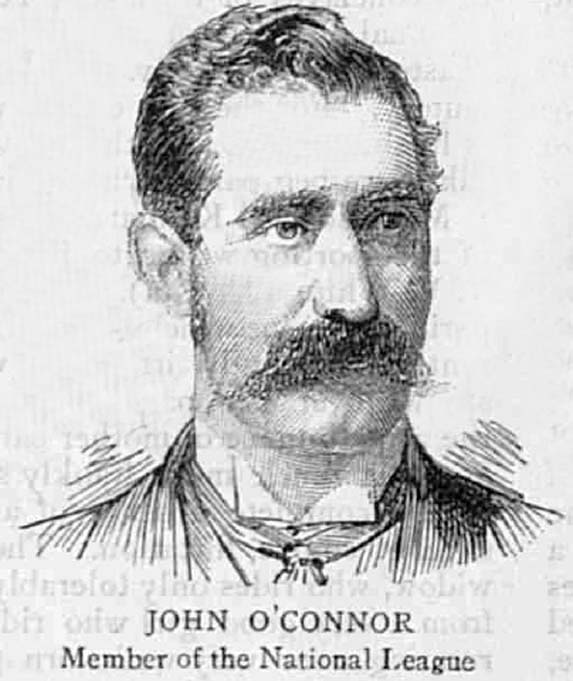

It was also proclaimed by more prominent members of the public like Irish nationalist and Member of Parliament, John O’Connor (1850-1928). O’Connor was vocal in his protestations and in 1886, he marched with others from Cork railway station, crying ‘Three Cheers for Poff and Barrett.’ He was subsequently called to account for the demonstration at the Special Commission of 1889.3

During the proceedings of the Commission, O’Connor explained that he was protesting in Cork against the system of packed juries. He was asked if he had publicly stated that Poff and Barrett were executed by the authorities ‘who knew they were innocent’ and he stated that government officials at Castleisland ‘had sufficient information to know that the men were not guilty, and know who the guilty men were.’

When asked to produce evidence to support his statement, he said, ‘I am told there is a place called Australia but I don’t know positively that there is.’4

In 1890, James Luke Doyle, rate collector and member of the New Ross Board of Guardians, recalled how he had been imprisoned in Clonmel jail with Poff under the Coercion Act, and described him as ‘as innocent as an unborn babe.’ 5

Fifty years after the convictions of Poff and Barrett, the general belief in their innocence was enshrined when a contributor to The Schools’ Collection put on record that ‘Thomas Browne’s assassins are not known.’

Despite the collective cry of innocence, Poff and Barrett remain on record as murderers.

Thomas Browne: The Theories

The absence of a motive remains one of the overwhelming aspects of the case. The Crown as prosecutors suggested that motive was not essential in those times of agrarian violence, but it was a weak statement. A man was shot dead in broad daylight while at work on his farm and it was strange to suggest that this was a random act, carried out without purpose.

In the wake of the murder, a motive was sought. Browne was described as industrious, hard-working, on good terms with people, including his neighbour, James Barrett, with no known enemies.

A number of theories were put forward and none of them implicated Poff and Barrett. One theorist suggested Browne was a victim of his own success:

And now people will ask, if the deceased man was on such friendly terms with those around him, if he was such a good neighbour and kind to the poor; if he had not taken up an evicted farm or otherwise transgressed the unwritten law of the Land League, why is it that his life was taken by emissaries as, no doubt, the two assassins were? The answer is that although he had not committed any of those so-called offences, still he had offended in another respect – that of being too prosperous, and too honest.6

A finger of blame was pointed at two labourers, Bryan Sweeny and Denis Daly, who had not turned up for work on the day of the murder:

A strange occurrence, remarked on by the coroner at the inquest, was given in the evidence to the effect that on Sunday the deceased man hired two labourers at Castleisland to come on Monday and work for him for a week, but neither of them came, and as the coroner remarked, it seemed they kept away in consequence of what was to take place as more than likely they would be witnesses of the scene if they went to work on Browne’s farm.7

There was a suggestion that Browne had had differences with the labourers.8 However, this does not seem to have been pursued by the police, as far as the record shows. Mrs Browne suggested the labourers had not turned up for work because of the wet weather.9

Another theory was raised in relation to turf cutting:

A report had got circulated today that deceased prevented some of his neighbours on the property to cut some turf on that portion which he purchased.10

Certainly, if true, access to bogland was something that might not have been taken lightly. In June 1886, Patrick Tangney of Ardteegalvan, near Killarney was shot dead by moonlighters. Tangney was a bog ranger for landlord Richard Going and his death followed a dispute about turbary rights.11

The police do not seem to have pursued this line of investigation in any serious manner, if at all. It was reported that the Castleisland police were ‘prosecuting their inquiries with vigour but up to the present there seems but very little chance of their efforts being rewarded with success’:

No arrests have been made except that of two men who were taken into custody yesterday morning, David Fitzgerald and C O’Connor and both of these were discharged, having satisfactorily accounted for their whereabouts on the evening of the occurrence.12

Browne’s neighbours were Fitzgerald, who had become his tenants, as explained by Mrs Browne during the trial, under examination of Mr De Moleyns:

Formerly my husband used pay rent to the Fitzgeralds but he bought the lands and the Fitzgeralds became his tenants; on the morning of the murder my husband got rent from Fitzgerald.

It was suggested that unfriendly relations between the two families existed.13 It had been rumoured that Browne intended to evict the Fitzgeralds on the expiration of their leases in March 1883.14

This theory appears to have been pursued more seriously than the others. If Browne was a marked man, as had been rumoured by John Dunleavy, certainly the Fitzgeralds had shown a solid alibi for the day of the murder. At the trial, Sub-Inspector Davis of Castleisland, questioned by the defence, stated:

To my knowledge the Fitzgeralds were not arrested at all. Their absence was accounted for. They spent the day in a public-house opposite my lodgings in Castleisland (laughter).

Fifty years after the murder, the rumoured involvement of the Fitzgerald family persisted. It was recorded in The Schools’ Collection:

Thomas Browne was suspected of having intended to grab the land of Paddy Sean Og.15

Retracing the Footprints of Poff and Barrett

Of all the theories, only the association of Fitzgerald had any bearing in the case against Poff and Barrett. On the day of the murder, John Dunleavy had called at the home of James Barrett and asked him to accompany him to the farm of the Fitzgeralds. Dunleavy wanted to get the loan of a ladder from Patrick (Paddy) Fitzgerald.

On arrival, the men found that Fitzgerald was not at home. They went into Fitzgerald’s haggard and found there at work a man named Michael Moynihan.16 Moynihan would not give the ladder to Dunleavy.17

Peter O’Brien QC, for the Crown, tried to attach motive to the men seeking a ladder ‘for some purpose of business.’

Forsooth Dunleavy went there for a ladder … Their subsequent conduct would show whether these men were intent on legitimate business that morning … Why should he [Dunleavy] require Barrett to accompany him? Was it for the sake of his conversation or was it to carry the ladder.

As John Dunleavy and James Barrett left Fitzgerald’s, they met Poff in a donkey car with Barrett’s mother.17a They went over to him and he asked where Maurice Healy lived as he wanted to buy cabbages. The three men then walked down the road towards Maurice Healy’s, meeting Bridget Brosnan on the way. Maurice Healy had no cabbages and Poff asked the two men to accompany him to Scartaglen where he had to collect a letter from the post office.

The prosecution tried to add further motive, observing that the men ‘were drinking and playing cards in Scartaglin during the day’ and – as if this act provided the key to some murderous plot – asked, ‘Why did they go drinking to Scartaglin?’18

Ultimately, the prosecution was unable to provide any further motive, if the loan of a ladder, playing cards and drinking in the village pub near the scene of the murder could be construed as evidence of murderous intent.19

The Victims

A great crowd attended the wake and funeral of Thomas Browne, who was laid to rest at Molahiffe, the burial place of his family.

The authorities refused James Barrett’s father ‘the privilege of investing his son with a new suit of clothes preparatory to his execution.’ The remains of Poff and Barrett were interred in the grounds of Tralee prison, over which now stands commercial property.20

In January 1883, a ‘monster funeral procession’ through Kerry was planned for Sylvester Poff and James Barrett, but word of the event reached the police.

There is no record of it having taken place.21

___________

1 ‘The Red Earl’s Vision’ published in United Ireland, 20 June 1885. Poet, author and journalist, Theodore Charles Christopher Hoste-Henley, son of Henry, a soldier, was born in Dublin in 1862. He married Elizabeth, fourth daughter of (late) James McDonnell, a baker, of Newry, on 4 July 1891 at St Agatha’s, Dublin. They had two children, Godfrey B. Hoste Henley (born c1893) and Muriel Hoste Henley (born c1899). Both children were living in Dublin with their widowed father on the Census of Ireland of 1911. Theodore contributed poetry to Irish newspapers during the period c1883 to c1910. He attended the funeral of Edmund Dwyer Gray MP, who died 27 March 1888, at which time he was on the staff of the Freeman’s Journal. His (mainly) political views were portrayed in his poetry which included ‘How Distress is Relieved’ (The Irishman, 21 April 1883), ‘The ‘Protestant’ Drum’ (The Irishman, 3 November 1883), ‘The Ruthless Earl with the Gloved-Steel Hands’ (The Irishman, 24 January 1885), ‘Well Done Tipperary!’ (Flag of Ireland, 17 January 1885), ‘Loyal Generosity (?)’ (United Ireland, 11 April 1885), ‘Sic Semper Tyrannis!’ (United Ireland, 13 June 1885), ‘The Red Earl’s Vision’ (Flag of Ireland, 20 June 1885), ‘Spencer’s Exit’ (United Ireland, 4 July 1885), ‘The Song of the Xmas Spirits’ (Weekly Freeman’s Journal, Christmas number, 1887), ‘The Death of Father Maurice’ (Weekly Freeman Christmas Sketch Book and Fireside Crackles 1889), ‘A Prayer for Ireland’ (United Ireland, 24 January 1891), ‘Drink Puppy Drink!’ (Flag of Ireland, 23 April 1892). A political poem about Mr Kettle and the budget published in Sinn Fein was reproduced in The Mid-Ulster Mail, 8 January 1910. Elizabeth Henley died from heart disease at 58 Florinda Place, Dublin on 28 December 1908, at age 48, described as a ‘proof reader’s wife.’ Theodore Henley, of 1 Fitzgibbon Street, Dublin, died on 26 March 1913 at age 51. He died from cardiac failure at 4 North Brunswick Street, Dublin, a hospital in the grounds of Richmond District Asylum (later the Richmond War Hospital), today the Carmichael Centre. The name Hoste-Henley is associated with the history of Sandringham Hall. See Sandringham Past and Present (1888) by Mrs Herbert Jones. My thanks to Marie Huxtable Wilson of Tralee for genealogical research of above. 2 The ballad, ‘You feeling Christians one and all,/Come listen unto me/It’s of an execution that happened in Tralee./How Poff and Barrett met their doom/May Heaven be their bed’ is found in The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0447, pp171-174. 3 Weekly Irish Times, 13 July 1889. Special Commission, day 103 (Members Day), cross examination of Mr John O’Connor, MP. Mr O’Connor confirmed he was a native of Mallow, Co Cork. 4 Of Poff and Barrett’s innocence, O’Connor stated: ‘Everybody told me so. And I may add that the two men themselves made dying declarations of their innocence to their priest who heard their last confession which is a matter of solemnity to Roman Catholics.’ He continued, ‘I took into consideration the fact that the people all said they were innocent, and that the men stated so on their dying declarations ... I knew these officials, and I know that they are capable of anything as mean, contemptible and tyrannical.’ The President of the hearing asked, ‘How many times are we going to ask this man to reiterate this shocking charge without any foundation?’ and O’Connor replied, ‘Not at all shocking to those who are acquainted with the police in Ireland.’ 5 James Luke Doyle (1851-1948) of Scullabogue, Carrigbyrne, Newbawn, Co Wexford. Stated in 1890 that he ‘had the honour of being arrested as a suspect and was in Clonmel jail for four months.’ See his statement in the Wexford People, 17 December 1890. James Doyle was released in March 1882. He died in 1948: ‘Mr James Luke Doyle, Scullabogue, Newbawn, Co Wexford, who has died aged 97, was from early manhood prominently associated with the Land League and all national movements. Following Forster’s Coercion Act, he was arrested and sent to Clonmel Jail. He was uncle of the Curtis family, Knockduff. The funeral to Courthoyle cemetery was largely attended’ (Irish Press, 22 January 1948). Mr Doyle’s brother was Thomas L Doyle of Ballyshannon who died in February 1938. In 1889, during the incarceration of William O’Brien in Tralee jail on charges of conspiracy raised against him, the prison was described as ‘a cold, damp, forbidding-looking structure of grey stone, much like other Irish gaols but less healthy than some. It lies on the outskirts of the town, almost isolated in low-lying marshy land. It was here that Poff and Barrett were hanged for the murder of Thomas Browne, a farmer at Castleisland, and curiously the execution took place on the day preceding that on which Mr Wm O’Brien was first returned to parliament after a hard struggle for Mallow in February 1883’ (Western Times, 13 February 1889). 6 ‘He was a specimen of what the real tiller of the land should be; and as such, was enabled to realize a large amount of money and therefore he should be done away with. No such man should be allowed live, who showed to the world that a man could pay his rent honestly, support himself and family, and at the time, put by so much money annually. No, that would be in direct contradiction to what the agitators relied upon as the foundation of their agitations – that a man cannot pay rent and support himself. It was, therefore, decreed that Thomas Browne should die and accordingly, on Tuesday evening, without a word of warning, he was sent before his Maker’ (Kerry Evening Post, 7 October 1882). 7 Kerry Evening Post, 7 October 1882. 8 ‘There is a further suggestion of a difference between the deceased and some labourers whom he had hired but who did not come afterwards to work for him as agreed upon but as they were compelled to remain away in consequence of the bad weather of the next few days rendering harvest operations an impossibility little or no importance is attached to their absence’ (Derby Mercury, 11 October 1882). 9 To Mrs Browne at the inquest: ‘Did they ever stay away before? They did on wet mornings. What were their names? Bryan Sweeny and Denis Daly’ (The Weekly Freeman and Irish Agriculturist, 7 October 1882). 10 The Weekly Freeman and Irish Agriculturist, 7 October 1882. ‘It is also stated that upon buying this land he prevented some persons from entering a bog where they had always been allowed to cut turf. The persons who have exercised that right positively deny this statement’ (Derby Mercury, 11 October 1882). 11 O’Donohoe Collection ref IE MOD/C24. The perpetrator appears to have gone unpunished. Material includes denouncement of the murder by Rev John Shanahan, parish priest of Barraduff, and reports about the dispute that led to Tangney’s death. 12 The Weekly Freeman and Irish Agriculturist, 7 October 1882. 13 ‘It was well known that an unfriendly feeling existed between Browne and the Fitzgeralds’ (Cork Examiner, 21 December 1882). 14 Derby Mercury, 11 October 1882. ‘If this were so, the tenants themselves did not believe it. They and deceased were on friendly terms and they are among the principal sympathisers with the unfortunate man’s family.’ 15 The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0447, Page pp174. 16 Haggard or haggart, an enclosed area near the farmhouse in which crops were stored. 17 James Barrett’s statement: 'On the morning of Thomas Browne’s murder, Dunleavy came to my house and asked me to go as far as Paddy Fitzgerald’s with him. We went to Fitzgerald’s and he was not at home; we were told he was in Tralee; we then went into Fitzgerald’s haggard. There was a man there named Michael Moynihan putting crosses on a rick of hay. He would not give the ladder to Dunleavy.’ James Barrett, in his Witness Statement dated 26 October 1882, also added: ‘Dunleavy said that what brought him to Fitzgerald’s was that he heard he was going to town, and he wanted to go too.’ 17a IE MOD/C69. Statement of James Barrett, 26 October 1882. ‘We turned out to go home, and saw Poff in a donkey’s car with my mother. We went out to Poff, and he asked us where Maurice Healy lived, as he heard he had cabbage for sale, and wanted to buy some. We went about twenty spades down the road to Mrs Brosnahan’s. Met her on the road. We followed on the road to Scartaglin, and then Dunleavy told Poff and me this was a bad place to be today – that he heard last night that Browne was to be shot today. We went on to Scartaglin and met Maurice Healy, and he had the cabbage sold. Poff wanted to go to Scartaglin for a letter, and at the Cross of Scartaglin we met Pat Brien. We went on to the village, and Dunleavy and Brien came up after.’ It is also learn from Judge Barry’s report of the trials to the Lord Lieutenant dated 16 January 1883 that Barrett ‘had a scarf on that day.’ 18 The fact that Poff and Barrett had a black dog with them and were dressed in clothes that differed to the description of the murderers given by witnesses had little effect. 19 The prosecution relied heavily on the word of Bridget Brosnan. See ‘Poff and Barrett: The Testimony of Bridget Brosnan’ on the O’Donohoe website. 20 The exact location has never been ascertained by descendants of the families. 21 ‘The police authorities in Ireland have received information that the sympathisers of the two murderers, Poff and Barrett, intend to get up a monster funeral procession to proceed through many of the disaffected districts in County Kerry. If this is done the police will probably disperse the processionists’ (Dundee Advertiser, 26 January 1883).