At the trial one name stood forth as a shining light and an honourable example to the Roman Catholic priesthood of Ireland, Rev Mr Scollard

In the aftermath of the two trials of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett for the murder of Thomas Browne of Dromultan, the Kerry Sentinel was calling on the government to investigate why John Dunleavy, a crucial witness, had been liberated and allowed to abscond before the trial.[1]

The Kerry Evening Post, on the other hand, described the verdict of guilty as ‘a triumph for law and religion.’ The journalist exhorted Rev Mr Scollard’s conduct as ‘a clergyman and a loyal subject’ which proved ‘his mission and calling’ and it was hoped that his bishop would show his approval at the earliest opportunity.[2]

Father Scollard had attended both trials in December 1882, as noted by Judge Barry in a report to Dublin Castle:

The Rev Mr Scollard sat close to the witness in court on both trials and the witness gave her evidence in his sight and hearing.[3]

Indeed, in his summing up of the case, the judge had more or less directed the jury in the significance of this support:

Such of the jury who were Catholics could not but believe that the old woman, after having got the sanction of the confessional, would not, and in the presence of her priest, have told a deliberate falsehood.[4]

The presence of Father Scollard in court was both daunting and powerful. He was the representation of the Roman Catholic Church, a symbol of authority, and as such, provided the main witness for the prosecution with a credibility that could hardly be questioned.

The convincing argument of Poff and Barrett’s counsel – that Bridget Brosnan had lied on oath at the inquest, that she had not come forward for more than a week after the inquest, that she had an existing grievance against John Dunleavy, or even that, on the day of the murder, two strange men wearing ‘long ulsters’ (coats) had gone into her house and gone away after lighting their pipes – paled in the heavenly authority suggested by her priest, her ‘cushla’:

I went to Currogh to the priest; I had taken the false oath before at the inquest, and the priest told me not to take it again; he said I should go to Castleisland and Archdeacon O’Connell for a certificate; I did go to Archdeacon O’Connell.[5]

It is worth pausing here to consider Bridget Brosnan’s change of heart, and the rewards of assisting police investigation at this time. Poff and Barrett had been tried in Cork, and during their journey there from Tralee jail in early December, they had travelled by train with others who were to stand trial, including John Casey, for the murder of magistrate, Arthur Edward Herbert.[6]

On 12 December 1882, a man named Jeremiah Horan of Castleisland wrote to the Kerry Sentinel about his experience in the investigation of Herbert’s murder. The letter is given here in its entirety, as it casts a rare light on investigative procedures at the very time Poff and Barrett were standing trial:

On Sunday the 19th November I was sent for by Sub-Inspector Davis, Castleisland, and interrogated as to the murder of A E Herbert, JP, whether I had any information to give which might lead to the detection of the criminals. In reply I informed him I had none, and after some further talk we parted, as I hoped for the last time on such business. However, this was not the case as on the evening of the 8th December, I was again sent for and taken to barracks, where I was kept until the following morning, despite my entreaties either to be informed of the nature of my visit, or otherwise to be left home to my three young orphans – unprotected, and with none to provide for them, even the poor pittance I could afford to give them. Between nine and ten o’clock on the morning following, I was taken before a gentleman whose name I was informed was Mr Starkie; with him I had a private interview for about ten minutes, during which time he had more than once informed me that if I had any information to give as to the murder of Mr Herbert, the existence of a secret society in the locality, or ‘anything else’ as he termed it, he was prepared to give me hundreds of pounds out of the heaps of money which he had at his command – together with the reward already offered for information which might lead to the detection of the murderers of A E Herbert. In fact during the whole interview, he was tempting me with British Gold bank notes, and the splendid life I could have in another country, to see if I would turn informer, perjure myself, and consequently be the ruin of numbers of men who could be for aught I know innocent of any crime. Without further comment, this sir, will show you the danger society is in while poor people like me are thus tempted with that ample inducement, English money.[7]

This is not to suggest that Bridget Brosnan did not see Poff and Barrett in the area on the day of the murder, or that she did not witness a number of men going into Browne’s field. There is no question Poff and Barrett were in the locality at the time of the murder. Indeed, an initial report of the murder confirmed this but reasoned that Poff and Barrett could not have committed the murder:

They were met on the road to the place where Poff lived (having passed the scene of the murder) by three little boys named Connor who were returning home from Kilsarkin National School. On their way home the children had to pass close by where the terrible crime was committed. From the statement made by one of them at the inquest on Browne they saw two men in the field with Browne, and they saw him fall. If this story be true, Poff and Barrett could not have been the murderers.[8]

What is absolutely certain, however, is that Bridget Brosnan did not witness the murder. She was at the gate talking to the victim’s wife when the shots that killed him were fired.

In his thesis, Murder at Dromulton, Peter O’Sullivan discussed the idea that the assassination of Browne was commonly known in the community:

Bridget Brosnahan, the chief witness, must have known. The sight of two men crossing over a ditch into Browne’s field was enough to send her running in panic to warn Mrs Browne.[9]

The ‘evidence’ of Bridget Brosnan alone was utterly flawed from the time of the inquest – one at which, it might be noted, no written statements were taken. There is no character witness for her, and no word in folklore about her role in the affair suggests she acted properly or with any element of bravery. Indeed, she is remembered as ‘a feeble, foul and vile old wretch.’[10]

The record shows that, but for her priest, Bridget Brosnan stood alone in her accusations against Poff and Barrett.

Priests and Politics

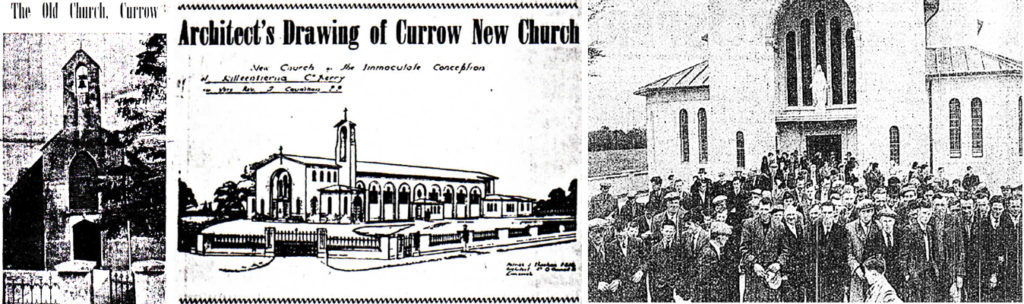

Bridget Brosnan lived midway between the RC chapels of Currow and Scartaglen – Dromultan, the townland in which she lived, divided by two parishes. In the year before the murder of Thomas Browne, a ‘fearful outrage’ occurred in the village of Currow.

Two brothers, Michael and John McAuliffe, a bailiff and civil bill officer respectively, had been attacked in the early hours by a party of armed and disguised men and money had been taken. Father Scollard denounced the outrage from the pulpit of Currow chapel. He urged parents to watch over their children and ensure they were home at a proper hour. He exhorted his congregation to pray earnestly that ‘God of His mercy may direct our rulers to give a good Land Bill’ – to restore friendly relations between landlord and tenant, and a country returned to peace and harmony.[11]

A return to the same, however, was not on the agenda of the Land League. Just a few months after the assault of the McAuliffes, a meeting of the Castleisland Land League took place in Currow attended by some 7,000 people. Rev Arthur Murphy, former president of the Castleisland Land League and, until a few months earlier, RC curate of Castleisland, numbered among the speakers. He was given a rapturous welcome.[12]

Father Scollard’s response to land issues clearly differed to the curate of his neighbouring parish. Fr Murphy advocated change, and shortly before the attack on the McAuliffes, had stood accused by one of them of intimidation.[13]

Just over one year on from the events in Currow, on Friday evening, 29 December 1882, Poff and Barrett arrived in Tralee from Cork prison on the 4pm train where ‘some thousands of persons congregated on the platform’ to see the condemned men.[14]

A great number followed their journey to the prison in Tralee where friends assembled outside the gates and ‘a painful scene was witnessed, all alike engaged in the heartrending screams.’[15]

Public sympathy was clearly behind Poff and Barrett, innocent men caught in a conflict that was many years from resolution. Indeed, the research of Peter O’Sullivan, up until his time of writing –1996 – revealed that:

The evidence of folklore is that, from the very beginning, the people in and around Dromulton never doubted the innocence of Poff and Barrett. Of all the older people in the area, who remember what their parents and grandparents had to say, I haven’t met with, or heard of one, who believes they were guilty. [16]

Under these circumstances, it is little wonder that Father Patrick Scollard was soon after moved on from the parish.[17]

Father Patrick Scollard

It is possible to follow, to some extent, the career of Father Scollard in order to measure, to some degree, his character. It is curious that this is largely achieved from reports in which he was involved in litigation.

In early 1884, Father Scollard was transferred to Dingle, where he remained as curate until 1898.[18] His ministry there during and in the wake of the Parnellite split caused considerable controversy.

In January 1891, his name appeared in a protest signed by 67 priests in Kerry against Parnell’s leadership ‘on moral and political grounds.’ As Patrick Ferriter of Dingle, who had been imprisoned on a number of occasions during the Land War, put it:

Father Scollard, having become emboldened by the success of his ‘Church versus Parnell’ propaganda, preached from the altar at Ventry on the same day that the followers of Mr Parnell were ‘guilty as such of breaking both the sixth and ninth commandments.’[19]

In 1892, a correspondent of the Kerry Sentinel described Father Scollard as ‘a pulpit politician’ who used ‘disgusting tactics’:

During the past fortnight Father Scollard embraced every means which the prostration of his high and revered calling could devise, unlimited intimidation and maledictions adnauseam being his chief stock in trade among the poor illiterate peasantry who never found until now the word Nationality on his lips.[20]

This matter was addressed some years later in the Dingle Petty Sessions when an action was taken by Very Rev Canon David O’Leary, Dingle, president of the League of the Cross Society, against James Kavanagh, caretaker of the Temperance Hall, Dingle, for possession. It transpired that the Temperance Hall had been closed temporarily during political differences caused by the Parnellite split. Father Scollard deposed that during the years 1890-1891 he had found it necessary to close the door of the society as he had been ‘grossly insulted by some of the members.’

During cross examination, Father Scollard was asked:

Is it a fact that you turned the members outside the doors; that you refused the subscriptions of some fishermen down at the quay, locked the doors of the society, and placed the present occupier, who at the time had a free house, in the hall without the permission of the committee? … Did you not then promise [the caretaker] that he would never be disturbed but to keep out the Parnellites?[21]

In 1898, Father Scollard was appointed parish priest of Glenbeigh. There he involved himself in church restoration work for which he appealed for funds.

In 1903, he helped to organise the Glenbeigh Feis and Home Industries Exhibition. The influence of the church at this time can be reckoned in a letter Father Scollard sent to the County Board that year requesting they change the date of the inter-county match between Cork and Kerry as it clashed with the Glenbeigh Feis. It was unanimously decided to write to the Provincial Council strongly recommending them to alter the date.[22]

Father Scollard also involved himself in matters of the district council such as road building of which he was accused of having personal interests. On one occasion he was asked, as a non-member of the council, to sit down, and on another, accused of ‘playing a trick until the roads were passed for him. Now there is no jubilee nurse to come there.’[23]

Father Scollard evidently sought reward for political favours, as illustrated in the following letter to Michael McGillicuddy snr:

Dear Mr McGillicuddy – I trust you will come to vote for Mr Moriarty next Wednesday. He got the road from Lickeen to your place passed before the County Council a few weeks ago and he will see that it is always kept in repair. So in gratitude in addition to many other reasons you and your son should vote for Mr Moriarty. A car will be sent to bring you if you require it. I hope you won’t disappoint us. P Scollard PP, Glencar[24]

In 1905, John Daly, principal of Curraghbeg National School, Glencar, took legal proceedings against Father Scollard when he proved Fr Scollard had unlawfully taken possession of his farm near the school. During cross-examination, Father Scollard was asked:

Are you aware, Father Scollard, that Mr Daly paid the head rent to the landlord for some years on your behalf? … Did not you speak at Glencar chapel that the farm had come on your hands and warn the people to have nothing to do with it, Father Scollard?[25]

In the same year, Fr Scollard was prosecuted by Daniel Sheehan, Glenbeigh, for assaulting his son, Michael, and expelling him by force from Keelnabrack National School, of which Father Scollard was manager.[26]

It transpired from the proceedings that there had been differences between the teachers of two schools, Glenbeigh National School and Keelnabrack, and that there appeared to be an organised boycott against Father Scollard.

The court heard that Michael Sheehan, aged 13, had attended Glenbeigh National School with three of his sisters but his father later sent him to Keelnabrack. On 20 October, Father Scollard went to the school and told the boy to go home and as he would not do so, Father Scollard caught him by the collar of the coat and pulled him out and trampled on his feet. Father Scannell, who was present, told Father Scollard ‘not to hurt him.’

Father Scollard deposed that if he trod on the boy’s feet when removing him it was entirely unintentional and that indeed, he himself should have the action ‘as the boy cut my hand.’ The boy returned to the school the next day but ‘did not go in, as he was afraid of Father Scollard.’

During examination, it was put to Father Scollard:

You know, Father Scollard, the General Lesson hung up in every school, ‘to live peaceably with all men?’[27]

Father Scollard was back in court in 1907 when he objected to the issue of a 7-day licence to George K Evans, Keelnabrack, Glenbeigh, who had built a 16-bedroom hotel at a cost of £2,000. Father Scollard’s objection was on the grounds that the building was ‘exceedingly near the church … it would be dis-edifying that drink should be sold under the shadow of the church’.[28]

Another case was brought in 1911 to restrain Patrick O’Sullivan, ex-parish clerk of Glenbeigh, who had called Father Scollard a ‘grabber’ during mass. The case was heard in the Chancery Division, Dublin, where it transpired that O’Sullivan, for reasons unknown, and much to his chagrin, had been replaced in his post as clerk. His subsequent behaviour towards Father Scollard ‘seriously interfered and continued to interfere’ with public worship in Glenbeigh church and was causing ‘great scandal.’[29]

Father Patrick Scollard died on 30 October 1914. An obituary recorded his achievements:

Hard work and difficulties never daunted Father Scollard. He was ever at the call of his people, ever ready to help them in their temporal as well as their spiritual concerns. He built a splendid school in Glenbeigh – a school that is a credit to the parish and that will be a lasting monument to its late pastor. He also built a much-needed presbytery, and carried out big improvements in the Glenbeigh and Glencar churches; in short wherever practical work was to be done Father Scollard was the man to do it.[30]

Fr Scollard was buried in the graveyard at Glencar.[31]

_______________________________

[1] The same report also interpreted Poff’s statement, ‘This won’t stop the work in Castleisland’ as meaning that hanging innocent men like him and Barrett would hardly bring about peace in the district (Kerry Sentinel, 29 December 1882). [2] ‘The Rev Mr Scollard was true to the dignity of his mission and calling and when he refused Absolution to the widow Brosnan until she should reveal the truth, he proved himself a faithful servant of his Divine Master. If all the priests of Ireland were equally true to their calling, murder would not have run riot as it has done throughout the land. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of the people know full well by whom the murders of Mr Herbert and others were committed, and it is difficult to imagine that none of the parties who hold those guilty secrets have ever resorted to the confessional. If they have not done so the old respect for religion must have vanished from amongst the people of the Castleisland district; if on the other hand they have resorted to the confessional it must be quite plain that public morality in the district has gained nothing by their visits. We trust that the Roman Catholic Bishop of this Diocese will take an early opportunity of testifying his approbation of the Rev Mr Scollard’s conduct as a clergyman and a loyal subject, and his Lordship’s action in the matter will be anxiously looked for by all right-thinking men in our community’ (Kerry Evening Post, 30 December 1882). [3] IE MOD/C69. Dorothy Dowgray Papers. [4] Irish Examiner, 23 December 1882. [5] Kerry Sentinel, 20 October 1882. ‘It was stated in Castleisland today that an old woman named Bridget Brosnan living in a cabin on the roadside at Dromulton had given the authorities information … It is believed that she gave evidence of the fact of two men, wearing long ulsters, having come into her house on the day of the murder and having gone away after lighting their pipes. She lives about 150 yards from Browne’s house. After the men had departed she went out and met Mrs Browne whom she told about the men being in her house’ (Kerry Evening Post, 11 October 1882). [6] Kerry Evening Post, 6 December 1882. ‘An armed party of moonlighters said to have numbered about forty visited the house of Mr Redmond Roche JP at Maglass on Wednesday evening last. It was stated that the party fired several shots outside and then entered the house and demanded arms, when two guns were given them. The facts however, seem to be that about six o’clock pm on the evening in question, Mr Roche, who was sitting by the fire in the dining-room, heard heavy steps in the hall and on going to ascertain the cause encountered several men, some of whom wore sacks and more were imperfectly disguised. They demanded arms and after a short parley they received two guns. The leader of the gang then addressed Mr Roche, and warned him to have nothing to do with Casey, the man at present in custody waiting trial for the murder of Mr Arthur Herbert. He said that Casey was not guilty, and that the man was present at the time who killed Mr Herbert. The leader then placed his hand on the shoulder of one of the disguised men, and he came forward towards Mr Roche and said it was he that killed Mr Herbert. He then produced a revolver from his pocket and said that was the weapon with which he committed the murder. The party then left without molesting any person in the house’ (Kerry Evening Post, 18 November 1882). [7] ‘How Informers are Manufactured,’ Kerry Sentinel, 15 December 1882. Identifying Mr Starkie was certainly naming and shaming. Starkie was Robert Fitzwilliam Starkie (1856-1934), Sub-Inspector of the RIC station at Cork Crime Department South-Western Division. He was grandson of Robert Starkie Esq, JP, of Cregane, Co Cork and son of William Robert Starkie (1824-1897) Resident Stipendiary Magistrate at Queenstown, Cork, and Frances Maria, daughter of Michael Power Esq of Waterford. Robert Fitzwilliam Starkie was born in Mayo where his father had been appointed RM at Belmullet in December 1854 (from 1859-1863 he was in Sligo). He married Marion Awdrey Williamson and had two sons, Melville and William. Robert Fitzwilliam Starkie CB JP of 85 Cornwall Gardens, South Kensington, late of Cregane Manor, Roscarbery, Co Cork, former member of Appeal Tribunal under Profiteering Act for City and County of Cork died 2 January 1934 aged 78. His siblings were Walter Fitzwilliam Starkie (1853-1878) who died young and ‘had many of the qualities of Thomas Davis’; William Joseph Myles Starkie (1861-1920), last Resident Commissioner of National Education of Ireland; Edyth Harriet Gertrude Gabrieth Starkie (1867-1941) who studied art at Slade and married illustrator Arthur Rackham (1867-1939); Leopold Reginald Starkie, 99th Royal Prussian Regiment, who married Marie, daughter of Ludwig Munzinger, Presiding Judge of the Superior Imperial Courts of the Zabern District, Alsace; Richard Starkie. ‘The Hon Captain Plunkett, SRM, attended by Sub-Inspector Starkie, has again proceeded to Castleisland for the purpose of making a further effort to discover who are the members of the assassination committee which undoubtedly exists in Castleisland’ (Kerry Independent, 1 January 1883). [8] Kerry Evening Post, 11 October 1882. [9] IE MOD/C73. Murder at Dromulton (1996) by Peter O’Sullivan, p31. [10] See O’Donohoe webpage, ‘Poff and Barrett: The Testimony of Bridget Brosnan’ http://www.odonohoearchive.com/poff-and-barrett-the-testimony-of-bridget-brosnan/ [11] Kerry Sentinel, 1 July 1881. [12] Further reference, ‘Too Honest for the Shoneens’: Father Murphy, Roman Catholic Curate of Castleisland. http://www.odonohoearchive.com/too-honest-for-the-shoneens-father-murphy-roman-catholic-curate-of-castleisland1/ [13] Ibid. [14] ‘From there they were conveyed to the Tralee jail under an escort of mounted and other police, followed some distance along the road by those gathered’ (Kerry Independent, 1 January 1883). [15] Kerry Independent, 1 January 1883. [16] IE MOD/C73. Murder at Dromulton (1996) by Peter O’Sullivan, p48. [17] ‘Clerical Changes: Rev P Scollard from Currens to Dingle’ (Kerry Sentinel, 4 March 1884). [18] The death of Canon D J O’Sullivan, parish priest of Dingle, occurred in 1898 following which Fr Scollard was appointed parish priest of Glenbeigh. [19] Kerry Sentinel, 16 May 1881. [20] Kerry Sentinel, 16 July 1892. Letter to the editor from ‘Wide Awake.’ Father Scollard addressed ‘private remonstrance’ to the Sentinel against accusations of intimidation, malediction, pulpit references and disgusting tactics. The editor responded, ‘We are willing to afford the fullest space for contradiction’ (Kerry Sentinel, 30 July 1892). 'Wide Awake' had addressed the Sentinel in February, describing Fr Scollard as he ‘who rules the Federation as guide, philosopher and friend.’ Fr Scollard, it seemed, had directed his congregation on politics but stated he would not counsel boycotting. The writer, however, asked that Fr Scollard ‘practice what he preaches … the absurdity of the proposed boycotting of the newsagent is furthermore apparent in that the Parnellite literature is sold and circulated exclusively by two Parnellite members in the town’ (Kerry Sentinel, 10 February 1892). [21] Kerry Evening Post, 26 May 1900. [22] Kerry People, 1 August 1903. [23] Meeting of Cahirciveen Board of Guardians and District Council, Kerry Evening Post, 10 May 1905. [24] Kerryman, 4 July 1908. The letter was dated 28 May 1908, addressed from Glencar. [25] Kerry News, 20 January 1905. The case was that in 1902, on Daly’s retirement, his son, Michael Daly, was appointed principal of the school by Fr Scollard. John Daly went to live in his native town of Cahirciveen and left his son in charge of his farm at Curraghbeg, which over about 30 years he had improved by building a stable, a cow-house and out-offices, fencing, drainage, a road, and six acres reclaimed. In 1903, Michael Daly was dismissed and in 1904, he left a man named Maurice Breen in charge of the farm. Mr Breen ‘became afraid of Father Scollard’s power’ and ceased to care it as Father Scollard had announced from the altar that the farm belonged to him and warned the flock against trespassing on it. Fr Scollard, manager of Curraghbeg National School, took possession of the farm, the landlord of which was Lord Lansdowne. Fr Scollard put Daniel O’Connor, teacher of Curraghbeg National School, in possession of the farm. Mr Daly sued Fr Scollard for eviction, and Fr Scollard counter-sued for rent alleged to be due by him. Daly later brought an action for damages against Daniel O’Connor, principal of Curraghbeg Male National School, and won; see Kerryman, 28 October 1905. [26] Kerry News, 20 January 1905. [27] The judge determined that ‘judging from Father Scollard’s quiet demeanour, he had come to the conclusion that he was not capable of doing anything hostile.’ [28] Mr Evans stated he had done ‘everything in his power to meet Rev Father Scollard’s objections and was willing to do more … he swore that there were no windows in the house looking into the church.’ His application was refused (Kerry News, 12 June 1907). [29] ‘Strange Scenes in a Kerry RC Church’, Rev Patrick Scollard and others v Patrick Sullivan, Kerry Evening Post, 16 December 1911, Northern Whig, 13 May 1912 & Kerry Weekly Reporter, 18 May 1912. In the absence of Patrick O’Sullivan, an injunction was granted against him. [30] Kerry Advocate, 7 November 1914. ‘Before his appointment as parish priest, he held curacies, among other places, in Killorglin and Dingle, and the kindliest memories are entertained in those places of his zeal and devotion as a priest. While in Glenbeigh he took a deep interest in the work of the Gaelic League; he was also closely identified with the National movement in the district. A true and holy priest, an earnest and sincere Irishman, his demise will be deeply regretted not alone by his brother priests in the diocese of Kerry but by all who knew him and his work and worth. Father Scollard, who had been in ill-health for some time, attained the age of seventy years.’ [31] Probate to Rev Patrick Brosnan, Allihies, Castletownbere and Rev James O’Callaghan, Eyries, Castletownbere. Funeral report, Kerry Advocate, 7 November 1914.