On the foundation of the Irish Free State, in a letter home to Ireland from the United States, Rev George Marshall, formerly of Mountnicholas, suggested that the relatives of Poff and Barrett should seek to have the remains of ‘those two victims of Irish landlordism and British hate’ disinterred from the old jail burial ground at Ballymullen for re-interment in their respective burial places.[1]

Almost one hundred years on, identifying the place where the bodies of Poff and Barrett were interred is hampered by the destruction of the Georgian building, constructed in about 1812.[2]

The prison served for more than a century until in 1916, parliament announced that four Irish prisons were to close: Londonderry, Dundalk, Galway and Tralee. Tralee prison closed in 1920 when it was announced that female prisoners would be sent to Cork or Limerick.[3] It was used as a military prison until 1925 when it was handed over to the local authority.[4]

Kerry County Council subsequently utilised the premises as a machinery depot. In 1995, Dick Spring launched the Lee Valley Action Plan which incorporated the redevelopment of the prison site. Kelliher’s Electrical, built on the site, incorporated the facade of the old jail. The high prison walls survive.[5]

From the records available, including a nineteenth century plan of the prison, it is possible to discern where executions were carried out.[6] In the Georgian and early Victorian period of the prison, public executions were conducted in the forecourt, which is now the general area of the car park in front of Kelliher’s. If the records available can be relied on, hanging was far from common there.

Murder at Castleisland Fair

The last public execution in Tralee prison appears to be that of 26-year-old Timothy Sheehan, described as ‘a proper honest fellow from west in Iveragh,’ for the murder of Denis Leane of Castleisland on 20 May 1852.[7] His execution – which was bungled – took place on 27 August 1852, witnessed by 3,000 people. It was reported to be the first hanging in the county for 15 years.[8]

Unearthing the Past

Public executions were abolished in 1868 and the executions of Poff and Barrett twenty-five years later (1883), evidently the first behind closed doors, were the first in Tralee for over 30 years, and duly reported to be so.

After this, the numbers who faced capital punishment increased and included Daniel Hayes and Daniel Moriarty, hanged on 28 April 1888 for the murder, on 31 January 1887, of James Fitzmaurice at Lixnaw; James ‘Fox’ Kirby on 7 May 1888 for the murder, on 8 November 1887, of Patrick Quirke at Liscahane, Co Kerry; Laurence Hickey on 7 August 1889 for the murder, on 22 November 1888, of Denis Daly at Meengamanane; Bartholomew Sullivan on 2 February 1891 for the murder, on 30 August 1890, of Patrick Flahive at Ballyheigue, Co Kerry.[10]

The male exercise yard of the prison became known as ‘the execution yard’ indicating that executions took place there within the high walls. The executions of Poff and Barrett, the first in 30 years, were high profile. Military patrols of the prison were increased to avert rescue attempts amid much public scrutiny.

The press was barred from being present at the executions but nonetheless, reports filtered out of events taking place within. From these, and from an eye witness account given about 40 years after the executions, it is possible to plot the precise area in which the bodies were interred.

Location of the Scaffold

The male exercise yards were detailed on the plan as ‘male airing yards.’ The condemned men were reported to be ‘in cells in the back part of the building’:

As they were within earshot of the yard where the trap was erected they must have experienced some torture from hearing the sounds of the workmen’s implements nailing together the rude timbers of the dread apparatus of death.[11]

Another report described the yard in which the gallows was placed as ‘at the extreme back of the gaol building known as the capstan mill yard’:

It was half filled with lumber today and only a small space round the scaffold was clear of broken pieces of wood and other articles.[12]

Another description of the event added further particulars:

The scaffold was constructed in the east angle of the gaol-yard, a substantial structure of about twelve feet high and ten feet square being boxed in all round.[13] A dozen steps led to the floor of the scaffold … walked from the cell in the hospital, where they had been pinioned, to the scaffold, a distance of about 18 paces.[14]

A further clue about the location was given in a report of those present outside the prison on 23 January 1883:

The inclemency of the weather did not prevent a considerable number of persons from assembling in front of the prison and upon the fields at the rere which commanded a better view of the portion of the jail in which the scaffold was erected … At five minutes past eight the black flag was hoisted in an obscure corner of the prison. It was not seen by any of those standing in the public approaches to the jail but some female relatives of the condemned men who were in the fields at the rere observed the ghastly emblem and at once broke out with wild and heart-rending lamentations which were soon taken up by the women outside and continued for several hours with every evidence of deep and heartfelt sorrow …[15]

It was also discerned from reports of the executions that when Poff and Barrett entered into ‘the hall which intervenes between the cells and the yard in which the scaffold was put up the procession halted and Poff and Barrett, speaking clearly and emphatically, made their declarations of innocence.’[16]

Eye Witness Account

To the contemporary clues above can be added the recollections of Jeremiah Benedict Mercer, who as a boy aged seven accompanied his father, Jeremiah, on a tour of the prison in 1921.[17] Also among the visiting party was Mr ‘Mongen’ Mahony, ex Royal Munster Fusiliers, and both men were guests of Timothy (Thady) Lawlor, ex Munster Fusiliers, about 60-75 years and at that time caretaker of the jail building. All three men had been compositors in Mr Raymond’s Printing Works in the Square, Tralee, in the premises afterwards Messrs Eugene Hogan, Decorators.

After an extensive tour of the jail buildings, the padded cell and condemned cells, into the chapel and down the steps to the execution yard, the boy listened fascinated and a little bit frightened as Mr Lawlor recounted in detail everything that happened when he, a young Fusilier, was one of a party of soldiers detailed for duty in the execution yard at Tralee Jail at the executions of Poff and Barrett.

In J B Mercer’s own words:

Mr Lawlor was one of a party of about forty soldiers detailed for duty and with bayonets fixed they marched from the barracks to the jail gates under the command of two officers. The party halted and the first two files – eight men, marched on into the jail directly to the execution yard. Mr Lawlor was one of this party under one officer. The next formed two lines in front of the jail gates where they remained until after the execution had been carried out.

It was the law that an armed military detail was present at executions and Mr Lawlor told how the officer placed one sentry outside the door of the execution yard and one sentry inside, one at each side of the steps leading to the scaffold and four men and himself drawn up in line facing the platform which was quite large. Under the platform and to one side was a large table on which the bodies of the executed men were laid.

The scaffold was at the far end of the yard and was quite high from the description of the layout. About half an hour after the soldiers had taken up their positions, there was a loud knocking on the door and the officer demanded, ‘Who goes there’ and the answer, ‘The Governor and Company. Open.’

Then the condemned men, flanked by four wardens preceded by the chaplain and the governor and others behind, came in and on up to the platform. In a short time he was placed on the trap and a warden stood on each side of the condemned man at arms’ length, with one hand resting on each shoulder of the condemned man and guided him to eternity as the trap was sprung. When the executions were over, the officer detailed two soldiers to escort the Chief Warden to the main gates where he nailed up the notice of execution.

Mr Lawlor had to wait until the burial was completed and then the party marched back to the barracks. At this point, Mr Lawlor walked over to a point a short distance from where we were standing and said, ‘They are buried there.’ ‘All executed men were buried in the prison.’

Jeremiah Benedict Mercer included a diagram showing the position of the two graves of Poff and Barrett, adding that the first man executed was placed in the grave nearest the wall.[18]

Though he was very young when he heard Mr Lawlor’s account, J B Mercer was adamant that he recalled correctly:

As clearly as this paper is before my eyes, I can picture that scene. People and events of that time are very sharply etched in my memory and I also clearly remember the high walls and as we came out, Mr Lawlor pointed to a large stone bin in which the lime was saved for burying the bodies. At the time I witnessed the description and account of the scene, the execution yard was beautifully kept, as was the whole area and was level and covered with a carpet of well-cut grass. I have given much thought to the position and direction of the graves and have no doubt whatever. Hoping the foregoing information will be of interest to you and useful to the relatives of the deceased men.

Determinations

From the plan of the prison, contemporary report and anecdote, technical engineer Mike Marshall, formerly of Mount Nicholas,[19] has made a detailed examination of the material. He reports as follows:

Ordnance Survey Ireland were not it seems allowed, on security grounds, to incorporate any internal details of prisons, barracks or other institutions if such detail might be of use to subversives. In the same way, when compiling the Census Returns, police or soldiers present in any barracks on the night of the Census were referred to only by their initials and rank. An architect’s or engineer’s drawing of the prison plan as it was in 1883 is needed to calculate, from the anecdotal accounts, where the grave sites were. The map of the new building, which was never fully completed, probably covers a different footprint to the original complex so it is very difficult to even establish a starting point.[20]

For now, it must be hoped that more information will surface in time, and that the exact burial site of Poff and Barrett will finally be identified.

Notes on Tralee Prison

Nine men were sent to Tralee jail on 2 February 1822 charged with the murder of Mail coach agent, William Brereton. Arthur Mahony Esq of Point, near Killarney, was committed the Tralee prison on 30 October 1828 charged with ‘administering unlawful oaths of a seditious tendency, ie, swearing allegiance to Mr O’Connell.’ Two others absconded. In March 1830, Denis McCarthy Launey and Ellen Connell were executed at Tralee prison for the murder of John Connell of Valencia, Ellen having conspired to murder her husband with McCarthy. ‘The Iveragh gentlemen present at the assizes have made a collection of 25l for the destitute children of Ellen Connell.’ Sylvester Sullivan was committed to the jail in December 1841 for the murder of Ellen Grady who he had ‘nearly cut to pieces’ in a fit of jealous rage. In 1847, the jail was reported to be ‘fearfully overcrowded and rife with deadly disease.’ The number confined was 335 of whom 74 were in hospital. In 1863, Martin Crean was governor of the jail when his son, Martin J Crean Esq MD, married the daughter of J Franks Esq, Swanton, Lancs. He retired in 1864 after ‘a long and faithful service.’ In 1866, the Inspector General of Prisons recommended that the prison adopt the ‘separate system’ as there was no separation between male and female prisoners, nor was there separation between ‘the hardened criminal and the juvenile offender.’ In February 1867, the prison had its share of inmates from the Fenian Rising. James Reilly, Michael Foley and James Fitzgerald were charged with an attack on the coastguard station at Kells and John Fitzgerald with attempting to swear in a man named William Rawson as a Fenian. A man named Mannix, arrested at Tarbert, was also interned on suspicion of involvement in the Kells coastguard attack along with Denis Lynch of Tralee and Mr Devane of Tarbert. In 1872, the governors of the prison resolved to apply for £4,000 for the reconstruction of the prison on the separate system. In October 1877, Cornelius Murphy of Caherciveen died in the prison, his death attributed to ‘congestion of the lungs.’ Four ex-militiamen were lodged in the prison in November 1880 for murdering a farmer named Shea near Kenmare. Mr Harkin, honorary secretary of the Creeslough (Donegal) branch of the Land League was committed to Tralee prison in July 1881 on a charge of inciting to murder. J D Sheehan MP for Kerry was escorted to Tralee prison in October 1888 under the Coercion Act on the charge of having advocated the adoption of the Plan of Campaign among Lord Kenmare’s tenants. It was observed in 1895 that a number of prisoners had been conveyed to Tralee prison from Cork owing to overcrowding there. ‘It is an interesting fact that amongst those confined in Cork prison at present are twenty-seven Englishmen.’ On 5 December 1898, Michael Maloney was received into Tralee jail sentenced to a month’s hard labour at the Newcastlewest Petty Sessions ‘for soliciting alms.’ On 10 December 1898, he was found dead in his cell having died in the night from heart disease. He was thought to have been an engine-driver on the Great Southern and Western Railway, a man ‘getting on in years. He was obviously enfeebled by disease and not far from his end when he outraged the majesty of the law by asking publicly for alms.’ For this he was given a month’s hard labour and was dead within four days. In 1923, seven people were conveyed to Tralee alleged to have looted on the occasion of the burning of the Listowel courthouse and police barrack.

Further reference, see letter to the editor of Kerry’s Eye newspaper (issue 19 August 1999) in which historian Peter Locke sketched the history of the prison. See also ‘Work halts at old Ballymullen jail’ in Kerry’s Eye, 24 September 2020 in which the ‘Convicts Quarry’ at the rear of the prison is discussed.[21]

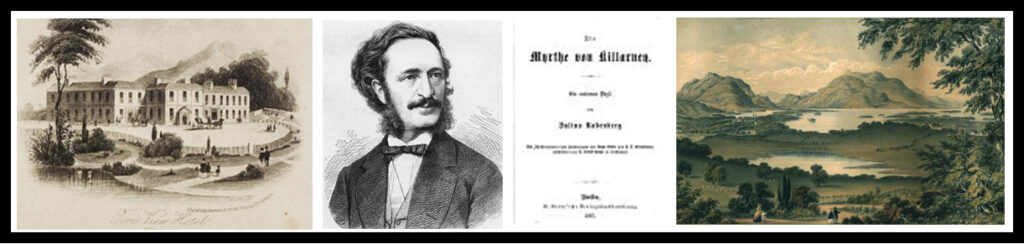

_________________________ [1] Kerry News, 18 March 1931. See ‘Remember Poff and Barrett’ (www.odonohoearchive.com) for biographical note on George Marshall of Mountnicholas. [2] Known also as Tralee Gaol, Tralee Jail, Ballymullen Prison or, sometimes, Ballymullen Barracks, and Kerry County Jail. A description of an earlier prison in Tralee was given in the Kerry Magazine, an extract of which was published in the Kerryman, 10 September 1904, ‘Murder of the Gaoler of Tralee Gaol.’ See notes on Tralee Prison at the foot of this article. [3] ‘The part of Tralee prison used for female prisoners has been closed, with an order that such prisoners be in future sent to Cork or Limerick, as may be convenient’ (Kerryman, 22 May 1920). [4] In 1923, troops discovered two tunnels in Tralee gaol, one from the cookhouse allotted to Irregular prisoners and the other from the hospital – both practically completed (Nottingham Journal, 6 February 1923). [5] It was reported in 1996, 'Since the gaol is a preserved building, every care is being taken to conserve its unique character.' The site is still occupied by Kelliher’s. [6] The plan of the prison would seem to have been drawn in line with the ‘Separate System’ under discussion from about 1866. ‘In the Kerry County Jail, as at present constructed, there was no separation between the male and female prisoners, and that therefore a proper classification of prisoners could not perfectly be carried out’ (From a report of Inspector General of Prisons, Tralee Chronicle, 13 March 1866). In 1872, ‘The governors of the Kerry County Gaol have resolved to apply at the forthcoming road sessions for a presentment for £4,000 for the reconstruction of the prison on the separate system … if it were not arranged on the separate system it could not continue to be used as a county prison’ (South Wales Daily News, 3 October 1872). [7] Timothy Sheehan (or Sheahan) and Edmond Moore were charged with having murdered 50-year-old Denis Leane (or Lane), a tenant of Lady Headley, on Thursday 20 May 1852 at Crag, Castleisland, by cutting his throat. Both men were tried and found guilty though the sentence on 24-year-old Edmond Moore was commuted to transportation on appeal to the Lord Lieutenant by Maurice O’Connell Esq MP and Daniel de Courcy McGillycuddy Esq JP (Nenagh Guardian, 1 September 1852). The murder appears to have been the outcome of differences between Sheehan and Leane. Sheehan, who worked for Leane, had earlier resided at the neighbouring farm of Bartholomew Murphy. The dying man, who survived for less than 24 hours, was asked by Dr Richard Harold Esq surgeon who committed the offence and he replied, ‘Death before Dishonour.’ Asked again, Leane said, ‘My own servant boy.’ During the attack on him, Moore held down his hands. ‘It has created a deep sensation in the peaceable and quiet neighbourhood of Castleisland ... the supposed principal in the bloody act was a stranger.’ Leane, who lived about three miles from Castleisland on ‘the old mountain road leading to Abbeyfeale’ was married to Judy. His eldest son, 15-year-old Maurice, and daughter Ellen, age 17, gave evidence at the trial. His daughter deposed that Edmond Moore, who lived closer to Castleisland than the Leanes, went to the Leane house on the morning of the fair and asked ‘Thade Sheahan’ to go with him. ‘He said he would, that he had a tumpane in for some person; that is an Irish word, ‘if you take my advice,’ said Moore, ‘you will stop at home’’ (Munster News, 26 May 1852). John Shanahan, brother-in-law of Leane, also gave evidence. Sixteen witnesses were examined for the Crown, Mr Brereton defended. See Irish Examiner, 19 July 1852 for report of trial of Timothy Sheehan and Edmond Moore for the murder of Denis Leane at Castleisland fair on 20 May 1852. [8] Cork Examiner, 1 September 1852. ‘Through the bungling of the executioner (who was the regular Limerick hangman), Sheehan was longer dying than is usual … The mother of the unfortunate criminal was present at the execution during which she fainted.’ Sheehan was attended by the Very Rev Dr McEnery, chaplain of the jail (‘who did not cease to perform this sacred duty till the fatal cap was placed over the face of the doomed one, and the bolt removed which launched him from the world of living men into eternity’) and the Rev John Mawe RCA and Revs Murphy, Moriarty and Higgins, RCCs. Sheehan was interred within the precincts of the gaol. [9] The Island of the Saints; a pilgrimage through Ireland (1861) by Julius von Rodenberg alias Julius Levy (1831-1914) Translated from the German by Sir F C Lascelles Wraxall (1828-1865). Rodenberg, who was born in Hesse, wrote of the proprietor of Torc View Hotel, ‘I shall never forget good, honest, Mr Hurley in my life for giving me this room. On two sides my windows looked out in the valley, and its every charm peered in at me ... I shall never pass more glorious days than I did here: when I think of them, I often feel as if it were all a dream’ (p185). Rodenberg was a little different to the customary traveller of the day as during his visits to the usual tourist spots, he took more particular interest in the people and their customs than the scenery. As one reviewer remarked, his book stood ‘in distinguished contrast’ to other books of Irish travel, ‘not alone to the garbage written from a hostile point of view for the English market, but to the hurrygraphs of Continental tourists generally whose views of the country and people have been, for the most part, limited to such observations as may be acquired from the top of a stage coach or the window of a railway carriage’ (Dublin Weekly Nation, 16 March 1861). His first encounter with Bridget, when he saw her at a spinning wheel outside her cabin near the hotel, is described on pp105-6 of his book. During his visit, he spent time with her, and accompanied her to a wake. Indeed, he seems to have fallen a little in love with her, and appears genuinely sad to learn that she planned to emigrate to America. ‘Reader, if ever you go to the Lakes of Killarney, you will find all as I have described it to you, with overflowing heart, and often with overflowing eyes, but never in sufficient beauty. But the cabin on the fairy hill will stand empty and deserted, one more ruin in the land of ruins, overgrown with nettles and thorns, a sorry sight, and if you ask, where is Bridget, you will learn she is no longer there’ (p179). He later published, Die Myrthe von Killarney. Ein modernes Idyll (1867) – The Myrtle of Killarney. A Tale. Torc View Hotel was operated by Jeremiah Hurley, who sold it in 1860 to the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Loreto Order). The Killarney foundation was the last authorised by Rev Mother Teresa who handed to the Bishop of Kerry the purchase money for Torc View Hotel in 1860 and within a month the Sisters began their work. After the death of Rt Rev Dr Moriarty, Bishop of Kerry, in 1877, it was acknowledged that ‘he established in Killarney a branch of the ancient educating Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary for the purposes of higher education; he found but seventeen Sisters of Mercy in the diocese, and he left 200, whilst amongst those who will mourn his loss for many a day, none will grieve with deeper and more deserved sorrow than the daughters of St Clare and the children of the saintly Nano Nagle’ (Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 17 November 1877). The Loreto Convent closed in 1989. Further reference, Fort Falvey A Record of O’Falvey of Faha (2016), p37. [10] Famous executioners of the time were James Berry, Murnane (otherwise Jack Ketch) and John Ellis. In the case of Moriarty and Hayes, it was observed that they walked ‘from the condemned cell to the old capstan mill-yard where the scaffold is permanently erected … twenty paces, paced in a minute or two’ (Cork Constitution, 30 April 1888). [11] Irish Examiner, 24 January 1883. [12] Ibid. [13] ‘The scaffold was constructed on the old principle being approached by some dozen steps and as the enclosing wall of the yard was rather low, a pit was excavated beneath the drop in order to prevent the strong cross-beam above being seen by any persons whose curiosity would prompt them to go into the fields at the back of the prison. In the beam were two strong iron clamps from which the two ropes depended and at the right hand side of the trapdoor in the centre was the switch for working the lever that made the trap, an apparently solid portion of the structure, but which unloosed caused the trapdoor to fly open downwards with a death dealing bang for the unhappy men placed on it’ (Irish Examiner, 24 January 1883). ‘The length of the drop was eight and a half to nine feet’ (Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 27 January 1883). [14] Ibid. ‘Both [Poff and Barrett] shuddered visibly when they entered the yard of death and beheld the grim structure in one corner from which they were so soon to be hurled in the prime of manhood … Poff mounted the steps rapidly, almost at a run, and Barrett followed at a slower pace … the adjusting of the ropes round the necks of the culprits was but the work of a few seconds, and then the clergyman having been warned off to a safe position by Marwood, he touched the switch and with a loud bang the trap-door swung downwards and the next moment the lifeless bodies of the two men were dangling from the fatal ropes … The bodies fell out of view of those present as the space below had been boarded in … In addition to those already named as being present at the execution, there were the parish clerk (Mr Collins) who attended on the priests, and a policeman (Constable Sealy) in plain clothes. The bolt was drawn about two minutes past eight and the black flag was at once hoisted in the back part of the prison. There were some thirty soldiers inside the prison and a large force of police the latter being in charge of Sub-Inspectors Maxwell and Holmes, while Mr Considine, RM, was in supreme command. This gentleman did not remain in the gaol during the work of execution.’ [15] Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 27 January 1883. [16] Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 27 January 1883. [17] IE MOD/C66. Account among papers donated to the O’Donohoe Collection by Pat Browne, a descendant of James Barrett (emailed courtesy Chalkboard). It is a handwritten letter dated 12 November 1969 addressed to ‘Townsman’ (no address) from Jeremiah Benedict Mercer, MBE, Royal Air Force (retired) of No 4 Langton House, Winthrop Road, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. It describes a memory from his childhood of a visit to Tralee Prison in about the year 1921 when he was aged about seven. Notes on the Mercer family of Tralee and an Aircrew Flying Log Book in the name of J B Mercer is held in IE MOD/C97. [18] ‘Which of the two I can’t say.’ [19] Mike Marshall’s branch of the Marshall family descends from George Marshall of Riverville House, Currans and his wife Margaret Walsh of Currans. Michael Marshall, Technical Director of ECSSA (Electrical Contractors Safety & Standards Association), has prepared a comprehensive genealogical record of his family, ‘The Marshall Family in County Kerry,’ from the twelfth century to date (24 pages). A copy is held in IE MOD/C61. He has also kindly donated a copy of the Marshall pedigree from Tristram Marshall, who came to Kerry with Sir Charles Wilmot in 1602, also held in IE MOD/C61. [20] By email with Castleisland District Heritage, 22 July 2021. [21] Records of Tralee prison held https://www.findmypast.ie/articles/world-records/full-list-of-the-irish-family-history-records/institutions-and-organisations/irish-prison-registers-1790-1924. My thanks to Gerard Murphy, Glenlara, for this reference.