The most remarkable fact in connection with the case is that both the men, though in separate cells, without any communication with each other, protested all through, and above all, at the last supreme moment, their absolute innocence. Derry Journal, 26 January 1883

In 1919, it was remarked that ‘Tralee Gaol contains the calcined remains of Poff and Barrett, Hayes and other innocent victims of the Land War – the people of Kerry should acquire possession of the jail to make it an edifice worthy of respect’.1

Another century of history now covers the memory of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett, and tons of concrete their unmarked graves at the site of the former prison, which was developed in the 1990s.2 Modern architecture, however, has not effaced events that occurred there in January 1883 nor has the passage of time diminished Poff and Barrett’s cries of injustice.

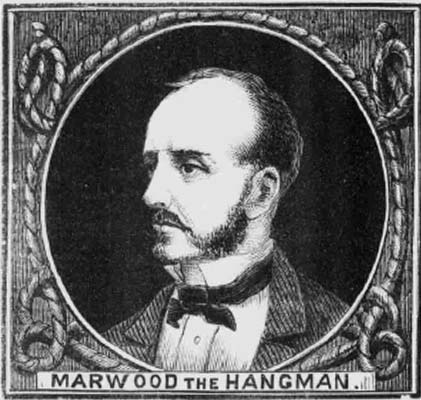

On Thursday evening 18 January 1883, five days before the men suffered the death penalty at the gallows in Tralee jail for the murder of Thomas Browne on 3 October 1882, William Marwood, the executioner, arrived in Tralee on the Limerick train to prepare the gallows.3

Marwood was accompanied by carpenters from Dublin as no local tradesmen would assist in erecting the scaffold.4 The gallows was constructed in the capstan mill yard, in the east angle of the prison yard, and was a substantial structure of 12 feet high and 10 feet square, boxed in all round. A dozen steps led to the floor of the scaffold which was hidden from any view outside the jail.5

On the wet and miserable morning of 23 January 1883, masses were offered across the county for the condemned men. In Tralee, Rev Father Sampson, a missionary priest, prayed for the ‘grace of a happy death’.6

At the prison, the press were refused admission to report on the execution. However, it was established that the men rose early, and declined food and refreshment. Fr O’Riordan administered the sacraments to them and celebrated mass in the chapel of the hospital.

They were then conducted into the pinioning room at a few minutes before 8am, where Marwood pinioned them, in the process of which both declared their innocence. From there, they were led to the gallows, a distance of about 18 paces.

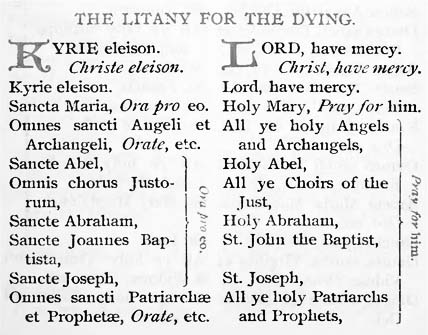

The melancholy procession consisted first of William Harnett, Sub Sheriff, and Robert Harris, Governor of HM Prison Tralee, followed by Sylvester Poff, who was attended by the chaplain, Fr H O’Riordan, and two warders; Barrett came next accompanied by assistant chaplain, Fr O’Callaghan and two warders; each man was attentive to the exhortations of the priest and fervently repeated the responses to the service for the dying as read by Fr O’Riordan. The jail officials, including Dr William Hilliard Lawlor, Surgeon to the Jail, accompanied by Marwood, followed.

Poff first and then Barrett mounted the steps of the scaffold unassisted; on the platform, Marwood strapped their legs, and placed white caps over their heads covering their faces. The nooses were then placed on their necks, Poff first, with some roughness. The bolt was drawn at five minutes past eight. Both men died simultaneously, and ‘with calm and dignified courage.’ 7

The black flag was hoisted.8

A short time after, the clergymen in attendance went outside the jail and informed the people that the dead men had declared their innocence on the scaffold.

The Irish Executive can do many things, it can proclaim districts, extinguish newspapers, and prevent members of parliament addressing their constituents; but it cannot prevent the universal circulation of the dying protestations of the dead Derry Journal, 26 January 1883

Inside the prison, the bodies of Poff and Barrett were left hanging for an hour, then removed and placed in shell coffins for the inquest, from which the press were also excluded:

A new surprise now broke upon the representatives of the press. They had waited for nearly an hour and a half outside the prison upon the understanding that the inquest was to be public but on seeking admission, they were point blank refused.9

The inquest began at 9.45am. Officials in attendance included Captain Thomas F Spring, District Coroner; William Harnett, Sub Sheriff; Robert Harris, prison governor and Dr William Hilliard Lawlor, prison surgeon.10 A small number of representatives of the press were reluctantly admitted to the jury; these would appear to have been Mr Harrington, Mr Raymond and Mr Brassill.11

After viewing the bodies, the proceedings were held in the Old Debtors’ Hall of the prison. A transcript of the hearing revealed the extraordinary difficulties experienced by the representatives of the press with officialdom. Mr P Divane, Tralee town commissioner, was threatened with jail and a fine of £2 for contempt for voicing his objection that reporters be excluded.12

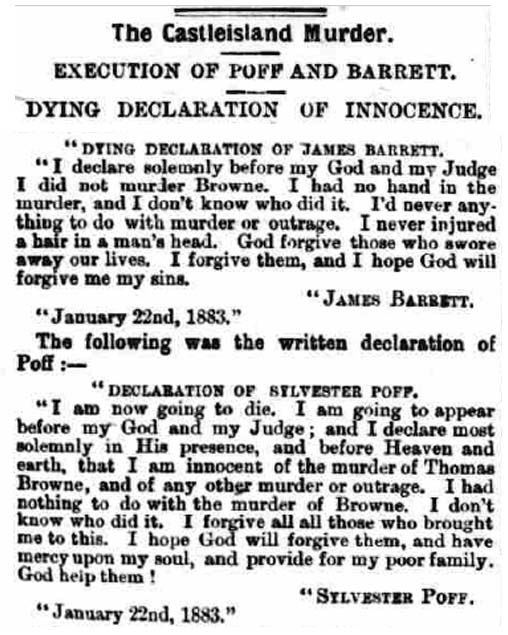

However, the efforts of the jury ensured that it was placed on record that Poff and Barrett had left written statements as to their innocence.

The jury returned the usual verdict:

We find that Sylvester Poff and James Barrett came by their deaths by fracture of the vertebrae with laceration of the spinal cord caused by hanging, in due course of law, about eight o’clock this morning at Her Majesty’s Prison, Tralee.

And to it was appended a rider:

We desire to express our great dissatisfaction at the action of the sub-sheriff in excluding the representatives of the press from the execution, and we also strongly condemn the exclusion of the representatives of the press from the inquest.

The inquest completed, the bodies of Poff and Barrett were interred within the jail.13

The Dying Declarations

It was stated that the object of excluding the press from the execution and inquest may have been to conceal from the public the fact that the unfortunate men left in writing the most emphatic declarations of their innocence:

Luckily they handed these testaments to the chaplain, and thus they have escaped suppression.14

It is to the eternal credit of Fr Humphrey O’Riordan, prison chaplain, that the last words of Poff and Barrett come down to us. The Dying Declarations of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett were rapidly published and widely circulated, the first appearing in print on the day of the execution.

There was much commentary. One writer stated the declarations contained an ‘assertion of utter innocence of the crime, or of knowledge of or connection with the perpetrators of the crime’:

We believe that men about whose necks lay the halter of the hangman and who had nothing more to hope for in this world – that Catholics upon whose souls gleamed the eyes of the Almighty would never utter, between their responses to the Litany of the Dying, the lie which would plunge them into eternal hell.15

The writer also remarked on the attempt to keep the statements away from the public:

If all this was done to keep from public ears a terrible accusation, it was of a piece with a policy which confesses its guilt by its desperation in endeavouring to stifle the truth. But through bolts, and bars, and bayonets, and the ring of sub-sheriffs and jail-governors, the dead hand struggled its way, and in the words it traces on the wall a blood-stained system reads a fresh denunciation.16

Mr John Kelly of the Tralee Board of Guardians spoke about the execution at the board meeting the day after the execution. Mr Kelly, who would fall foul of the law himself in the coming months, stated that he knew Poff well, ‘a gentle inoffensive, honourable man’.17

He described Poff and Barrett’s deaths as legal murder. That the dying declarations were true, he had no doubt:

I don’t care what any man’s religion may be as long as he believes in a future state. I don’t believe – no matter what his profession may be, even if I went as far as to say that he was an Atheist, but that he must believe the declaration made by them on the verge of the grave was true.18

An English paper commented on the ‘tragedies from Ireland’ and suggested ‘the tragedies on Tuesday were committed by Marwood under the sanction of the law’:

Even Lord Spencer, who, as Mr Froude said of an English queen, has already enswathed himself in an opi that which is likely to cling to his memory, must have some misgiving as to the propriety of the double execution on Tuesday … In the first place, there was not a particle of evidence to show any motive for the committal of the crime; the prosecution acknowledged as much. Men don’t commit crimes in Ireland without motives any more than they do in this country. In the second place they were convicted on the evidence of a single woman who might have been mistaken. And even this one witness on different occasions contradicted herself.19

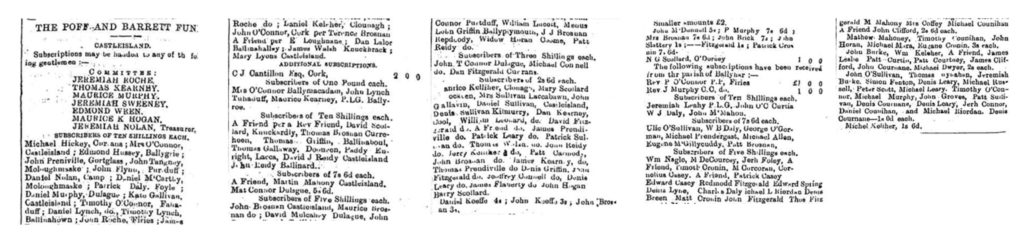

In line with Poff’s dying wishes, a fund was opened for the families of both men. People subscribed from all over the county, and names of contributors from Castleisland, Tralee, Killarney, Ardfert, etc, were published.

John Stack, vice-chairman of the Listowel Board of Guardians, opened the subscription in Listowel, contributing £2 himself.20

In the parish of Ballymacelligott, Fr John O’Leary, parish priest, opened the list there during Mass on the Sunday after the executions.21 He addressed a tearful congregation and said he hoped the fund would help Mrs Poff and the parents of Barrett ‘to get a new start in life’.22

Fr O’Leary described how he had visited Poff in his prison cell, and Poff had informed him that ‘he hoped for nothing but that God would not allow innocent men be hanged.’ He asked the congregation to offer up their fervent prayers for the eternal rest of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett and said that their prayers would not be needed long, for Poff and Barrett, he assured, were on the road to Heaven.23

Post Script

The Michael O’Donohoe Collection has received a donation of research papers from Dorothy Dowgray, a Poff descendant (http://www.odonohoearchive.com/poff-and-barrett-global-search-for-justice/). Included are documents which reveal that the authorities conducted an investigation following the publication of the Dying Declarations. Robert Harris, Governor of Tralee Prison, wrote to the Chairman of the General Prisons Board on 27 January 1883 to explain how Poff and Barrett had come by the writing materials.

He informed the board that Poff had requested the materials to arrange some family affairs on 19th January. They had been given to him on 20th January. On the 21st January, Mr Harris found that the assistant chaplain, Rev O’Riordan, had taken a portion of the paper to Barrett upon which the statements were made.

Robert Harris also stated that Poff proclaimed his innocence on being pinioned, the words repeated as nearly as possible by Barrett immediately after Poff. ‘I think it right to add that whenever I visited those prisoners, whether accompanied by the chief warder or any member of the visiting committee – they invariably declared their innocence of the murder of Thomas Browne.’24

________

1 Kerryman, 13 September 1919. 2 In 1916, parliament announced that four Irish prisons were to be closed, those of Londonderry, Dundalk, Galway and Tralee. Ballymullen (Tralee) prison closed in 1920 and was used as a military prison until 1925 when it was handed over to the local authority. Kerry County Council subsequently utilised the premises as a machinery depot. In 1995, Dick Spring launched the Lee Valley Action Plan which incorporated the redevelopment of the prison site. Kelleher's Electrical, built on the site, incorporated the facade of the old jail. It was reported in 1996, 'Since the gaol is a preserved building, every care is being taken to conserve its unique character'. In a letter to the Kerry's Eye newspaper in 1999 (19 August), Peter Locke sketched the history of the prison, which was built in 1812, and of those who died there: 'Tons of concrete and tarmac cover their resting places'. In 1923, troops discovered two tunnels in Tralee gaol, one from the cookhouse allotted to Irregular prisoners and the other from the hospital – both practically completed (Nottingham Journal, 6 February 1923). The polka, Tralee Gaol, is a tuneful reminder of the jail. ‘Murder of the Gaoler of Tralee Gaol’ described the earlier prison in the town (see Kerryman, 19 September 1904, extracted from the Kerry Magazine). 3 In the preceding days, Marwood, who also lost his life in 1883, had performed executions in Galway. He had also been in Galway the previous month, arriving in Dublin on Wednesday 13 December 1882, to perform the executions of the Maamtrasna Murders, Patrick Joyce, Myles Joyce and Patrick Casey. It is worth noting that at the time Marwood was present in Tralee jail, the ghost of Myles Joyce appeared within the precincts of Galway jail. The apparition was kept a secret at first by the officials who believed it a joke or delusion. But two soldiers on guard within the prison were followed by the ghostly figure which approached them and ‘actually touched their rifles’ before it vanished. The matron and warders of the prison were said to have applied for transfers. 4 Indeed, a week earlier, on Tuesday 9 January 1883, a force of military over one hundred strong and some forty of the constabulary paraded round the outer walls of the prison as it was rumoured that an attempt would be made to it up and rescue the condemned prisoners. See Kerry Sentinel, 12 January 1883. 5 Someone privy to the intimate conditions of the condemned men in the jail corresponded with the Freeman’s Journal. They observed that ‘Yesterday he [Marwood] resorted to a strange experiment – namely, the hanging of a sack of broken stones corresponding in weight to one of the condemned men. The result he pronounced thoroughly satisfactory’ (Freeman’s Journal, 23 January 1883). 6 ‘Several masses were offered up in Tralee this morning for the repose of their souls and in the parish church on Sunday evening the prayers of a crowded congregation were asked for the grace of a happy death to the unfortunate men by the Rev Father Sampson, who has been for some time past conducting a mission in Tralee’ (Freeman’s Journal, 24 January 1883). In Dingle, mass was offered for the eternal repose of their souls. ‘High Mass is to be offered up here on tomorrow for the eternal repose of the souls of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett. Printed cards, in mourning, are also to be posted on the prominent places outside the chapel doors asking for the executed men the prayers of the congregation. The money necessary to defray the expenses incurred in those pious works has been collected in this town [Dingle] solely through the exertions of Mrs Herlihy, formerly from near Tralee. It is only right to add that around this locality the belief that the men were innocent of the awful crime for which they had to suffer is almost unanimously felt’ (Kerry Sentinel, 30 January 1883). 7 The Irishman, 27 January 1883 and Freeman’s Journal, 24 January 1883. The report in the latter was from a special correspondent, and evidently a person privy to events inside of the prison. Marwood was expected to leave Tralee by the 5.15 pm train, where a large crowd had assembled, but did not appear. He left Tralee the following morning, on the 6am train on the North Kerry line. 8 A group of soldiers assembled in one of the drill fields was said to have cheered on the hoisting of the black flag. ‘We think a wise discretion would be exercised in the interests of public peace by the removal of this regiment. This is the mildest thing we can say under the circumstances. These heroes may have reverentially saluted Mahomedan freak of the holy carpet in Egypt, but they could not be expected to conduct themselves when the spirits of the two Irish Catholics were passing before their God (‘The Gallant 80th’, Kerry Sentinel, 26 January 1883). 9 The Freeman’s Journal, 24 January 1883. ‘They remonstrated with the coroner and his reply was that he would readily admit them himself but the governor had read the rules to him and stated that they empowered him (Mr Harris) to exclude everyone but the jurors and officials until the execution was completed and the bodies buried. The coroner then consented to summon three or four of the representatives of the press upon the jury and this expedient has enabled me to forward a detailed report of the proceedings at the inquest.’ 10 Robert Harris, deputy (and in 1863 acting) governor of Tralee, was appointed governor in succession to the late Mr Christopher Gallwey, brother of the agent of the Earl of Kenmare, in October 1870, on a salary of £200 a year. The High Sheriff was at that time in Italy ‘and his subordinate it is that takes upon himself the whole responsibility of excluding the representatives of the public journals’ (Freeman’s Journal, 23 January 1883). 11 For further reference to Kerry press, see page, ‘Stop Press: Michael O’Donohoe and the Kerry Newspapers’ on the O’Donohoe website. A Mr McKay was also named as a juror. 12 The inquest was covered by a number of papers including the Freeman’s Journal, 24 January 1883 and The Irishman, 27th January 1883. 13 Harrington’s impassioned summation of press reportage of the execution was contained in the item, ‘The Herd of Swine’ in the Kerry Sentinel of 26 January 1883. He also wrote, ‘We could unmask these informants of the government whose malignant misrepresentations, working through stupid mediums on a fluttered Executive, got these innocent men hanged, but for many reasons we refrain.’ 14 The Irishman, 27 January 1883 and Flag of Ireland, 27 January 1883. 15 Flag of Ireland, 27 January 1883. 16 Flag of Ireland, 27 January 1883. ‘These words were written by hands now rotting in the prison quick-lime. They were spoken by two men who stood upon the threshold of Eternity. There is nothing vague or incomplete about them. They contain an assertion of utter innocence of the crime, or of knowledge of or connection with the perpetrators of the crime, for which the men were suffering death, or of any other outrage which men might lay to their charge. We, at any rate, believe these words – if we are permitted to say that much.’ 17 Kelly was charged with using seditious language. See The Queen at the prosecution of Sub Constables Conroy and O’Brien v John Kelly, TC, Tralee, for having on the night of 7th April 1883 used seditious language. Case in Kerry Sentinel, 17 April 1883. He was arrested in the offices of the Kerry Sentinel on Monday 23 April and committed to a fortnight’s imprisonment. He was at the time in company with Edward Harrington and John Stack TC Listowel. At the jail gate, Kelly shook hands with a number of officials including M Quinlan, PLG. Report of arrest in Kerry Sentinel, 24 April 1883. He was released two weeks later: ‘On Sunday morning Mr John Kelly TC was released from Tralee Gaol after a fortnight’s imprisonment in default of bail, as reported recently in our columns. Mr Kelly looks little the worse of his dip. He was met at the gaol gate by a number of friends’ (Kerry Sentinel, 8 May 1883). 18 Details of the meeting of the Tralee Board of Guardians on Wednesday, 24 January 1883, were published in the Kerry Sentinel, 26 January 1883. ‘Mr J Kelly, ‘I believe you would agree with me when I say that Poff and Barrett would now exchange places with the Lord Lieutenant, even with the Queen, who sent him over here to do the dirty work of a coercive government. The dying statements of Poff are a telling and terrible reply to the cool answer from Dublin Castle which has been read. I don’t care what any man’s religion may be as long as he believes in a future state. I don’t believe – no matter what his profession may be, even if I went as far as to say that he was an Atheist, but that he must believe the declaration made by them on the verge of the grave was true; and we must also admit that they died innocent; that they were murdered – if they could be legally murdered – that the men who died on yesterday were not the perpetrators of the one of which a Cork jury found them guilty. Sylvester Poff – I knew him well – was a gentle inoffensive, honourable man. He was unfortunately one of a class in this country who are subjected to very harsh treatment by their landlords – evicted tenants. He was evicted from his home, arrested as a suspect, an outcast upon the world – this inoffensive and honourable man who died such an edifying death. Though they tried to make it an ignominious death, Sylvester Poff, I say here with pride, was a brother [illeg] of mine, the man who yesterday paid the penalty of the law through some misrepresentation. I don’t wish to touch further on the subject because you gentlemen, as well as I believe them innocent. I can now only offer a suggestion that his last words when he made an appeal on behalf of his family will not be forgotten’. 19 ‘The Latest Tragedies’ Kerry Sentinel, 26 January 1883 (from the Echo). 20 ‘At the Listowel Board of Guardians yesterday, a subscription list was opened, on the suggestion of Mr J Stack, Vice-chairman, in aid of the family of Sylvester Poff, executed last Tuesday in Tralee Gaol. Mr Stack himself subscribed £2 and all the other members also subscribed’ (Kerry Sentinel, 26 January 1883). The fund seems to have wound down in April 1883. A list of subscribers from exiled Kerry people appeared in the Kerry Independent in July and August 1883. 21 Fr O’Leary addressed the congregation on Sunday 28 January. He opened the subscription list with his name in the sum of £2. 22 Fr O’Leary spoke of how he had seen several people reading accounts of the execution in tears, and asked his congregation to hearken to the last dying request of Poff that his family be taken care of. ‘You know that family much better than I do,’ he said. ‘It consists of an aged and respectable mother, a sister, a wife, and four young children … together with two orphans belonging to his deceased sister … That was all he had in the world to leave us; he was evicted and cast homeless on the world and having nothing left to us but his family, he bequeathed that family to the kindness and generosity of his neighbours (At this a number of women burst into tears).’ 23 Kerry Sentinel, 30 January 1883. 24 IE MOD/C69. Robert Harris wrote to the board again on 9 February 1883 to inform them that he had only Barrett’s dying declaration and not Poff’s which was ‘probably taken by the person, whoever he was, that communicated it to the press.’