Nestling in the heart of the Kerry mountains, the progressive little town of Killorglin is to be found. Its picturesque situation is very well known to the tourist; but outside Kerry and portions of Cork and Limerick the fact that it holds a curious and unique annual gathering called ‘Puck’ Fair is known to very few. The fair is held each year on August 11th, it lasts practically for three days, and presumably it derives its title from the goats that are to be found in such large numbers in the surrounding mountains – M P Ryle, The Kingdom of Kerry (1899)

An information plaque near the Puck Goat statue in Killorglin, Co Kerry, where the famed Puck Fair is held annually, gives the following information:

For hundreds of years, a male mountain goat has been enthroned as King of Puck Fair in Killorglin town. The Puck Goat reigns over the fair held on August 10th, 11th, and 12th of each year. King Puck is a symbol of a vast tradition whose origins are lost in the mists of time.[1]

Various accounts of the tradition of elevating a goat at the Killorglin fair, described as ‘quaint and almost druidical’ in its ceremony, have been given over time.[2] This version by P F Doyle ascribes the origin to the times of the Williamite War in Ireland:

When Sarsfield rode out from Limerick to intercept King William’s cannon, on the 10th August 1690, he and his troopers ambushed in the Keeper Mountains. The first intimation they got of the near approaching enemy was from the flight of a flock of goats on the opposite hill. Sarsfield sent scouts to reconnoitre. History tells the rest of this part. On the 11th of August 1691 the people of Killorglin and its vicinity assembled to celebrate this victory and decorated a Puck Goat with green ribbons and a saddle.[3]

In 1898, ‘E. Evans’ addressed a letter about Puck Fair to the Kerry Weekly Reporter, describing the above as absurd, and giving the tradition earlier date:

King James the First, granted Jenkin Conway a patent, dated 10th Oct 1613, to hold one fair in the village of Killorgan (Killorglin) on Lammas Day, 1st August had been always a notable day in which games of divers kinds were celebrated by the ancient Irish, and which were handed down to them by their pagan ancestors. This was continued to be held yearly until 1772 when a new patent was granted to Conway Blennerhassett Esq who succeeded through inter-marriage to Jenkin Conway’s estate, to hold three annual fairs at Killorglin. This patent is dated 19th March, 12 George III, empowering Conway Blennerhassett to hold fairs on May 19th and 20th, June 30th and July 1st and November 18th and 19th. The Lammas Day fair was omitted in the second patent, and on the 1st August 1772 (which was equal to the 12th August since the change in the calendar) the inhabitants of the town assisted by the people in the surrounding neighbourhood, held their own accustomed fair notwithstanding it had been prohibited by proclamation and force. However, Mr Blennerhassett, yielding to the wishes of the inhabitants and respecting their old custom, allowed the usual two days fair – 11th and 12th August, to be held every year in addition to the three fairs named in his patent.[4]

Elsewhere, the actions of Oliver Cromwell are suggested as instigating the festival:

While the ‘roundheads’ were pillaging the countryside around Shanara and Kilgobnet at the foot of the McGillycuddy Reeks, they came upon a herd of goats grazing on the upland. The animals took flight before the raiders, and the puck goat broke and became separated from the herd. While the others headed for the mountains, the male went towards Killorglin on the banks of the Laune. His arrival there in a state of semi-exhaustion alerted the inhabitants of the approaching danger and they immediately set about protecting themselves and their stock. In recognition of the service rendered by the goat, the people decided to institute a special festival in his honour and this festival has been held ever since.[5]

A Milesian Queen coming to see Puck Fair, died in Gleann Scothaidhe Diarmuid and Grainne and Fionn the Bold Joined in the revels in the days of old.[6]

Some authorities dismiss the seventeenth century as too recent, and maintain the fair has its roots in the pre-Christian era, ‘beginning in the days of the legendary Diarmuid and Grainne who are believed to have been responsible for the many spectacular exploits along the banks of the River Laune.’[7] A 1960s journalist went along with this view, describing the event as ‘some sort of fertility festival held at harvest time going back further even than St Patrick’ while observing that ‘a certain amount of fertility does go on at Puck Fair.’[8]

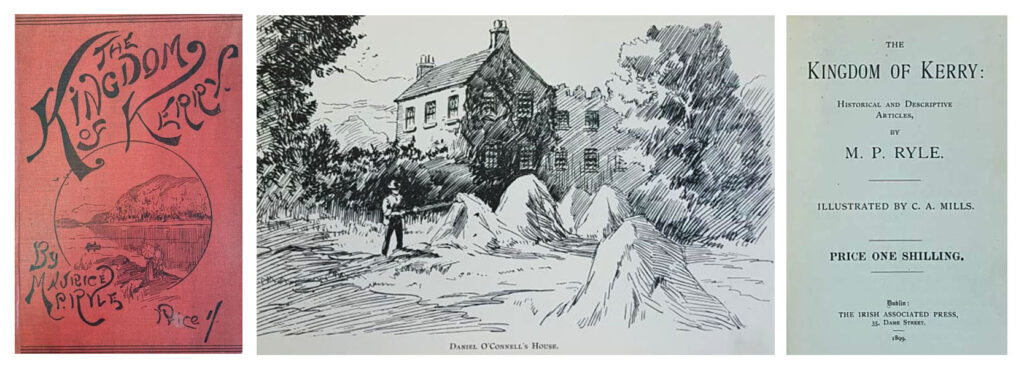

A general belief in the 1960s was that ‘it all started as a 19th century tax-dodge.’[9] This may emanate from another tradition that Puck Fair was first held in the early nineteenth century, in 1808 to be precise, to avoid losing toll income. In this, The Liberator, Daniel O’Connell, finds place in the theories:

Daniel O’Connell gave a legal opinion to a local landlord, Harman Blennerhassett, who had been prevented from levying his customary tolls on Killorglin Fair by the Viceroy. ‘You have only one way out,’ O’Connell said, ‘goats are not covered by this document. You should be legally entitled to hold a goat fair, and levy your tolls as usual.’ So Killorglin Fair became a goat fair and to drive the point home the most majestic wild puck goat on the MacGillycuddy’s Reeks was brought to Killorglin and hoisted on a lofty stage to preside over the fair.[10]

Someone signing themselves ‘Centurian and Patriot’ also placed the tradition in the early nineteenth century, and was adamant his version was correct:

Let it be understood that I will fight through the Sentinel against anyone who will say that my knowledge of the origin of ‘Puck’ is wrong. In the years 1800 to 1808, a resident gentleman proposed to the few inhabitants of the ‘New Killorglin’ that there should be a yearly fair started so that it would commence with the ‘New Town.’ and give a chance to the poor people of the parish and ‘village.’ The inhabitants at once agreed, and were only too glad to have their little village made the place of the fair … In 1806, the establishing of the new fair was published, and in six months afterwards the committee met to discuss the name of the fair. It was then proposed that a bonham, goat and calf should be placed on a raised platform, in a conspicuous place, but the committee disagreed as the trouble of hoisting these three animals was too much; therefore they agreed that the ‘puck’ would be the most picturesque, as he was also the king of the mountain animals, and the parish of the ‘New Killorglin’ so poor that the goat was the commonest and most highly praised by the people at that time; also, we read that the goat was held in great veneration by the Druids. … I can also give the name of the gentleman who first started the fair.[11]

In 1928, Mr Batt Dwyer, Killorglin District Court Clerk, disagreed with the above versions and dated the tradition to the 1830s:

The people of Killorglin district, with those of every Catholic district in the country, resisted to the fullest the imposition of the Protestant Tithe tax, whereupon the tithe-gatherers and bailiffs swept their stock from the mountains. After a big ‘round up’ the bailiffs arrived one evening at the ford where Killorglin’s substantial bridge now stands. While endeavouring to force a large seizure of mixed animals across the river, a huge ‘Puck’ goat broke away and naturally faced back up the mountain. His example was quickly followed by the rest of the herd, and the bailiffs, being too exhausted after a long, hard day’s work to attempt a recapture, resumed their journey to Tralee with but a very meagre haul from the people of Killorglin. It was a ‘Puck’ goat that defeated the seizure, and in fitting celebration of this achievement, the most presentable representative of the species, on each anniversary day, was bedecked and beribboned and hauled to the top of Castle Conway, the ruins of which may still be seen at the rere of Sheehan’s licensed house, close to the Carnegie Hall.[12]

Castle Conway was also mentioned in other traditions about the fair. This one was given in 1912 by ‘the oldest inhabitant’ of Killorglin:

About the year 1820, there used to be a goat fair held in Killorglin, which at that time consisted of only a few thatched cabins. The district for miles around it was then badly cultivated, badly drained, and badly fenced; hence thousands of these little animals found their way on the 11th of August each year to the village of Killorglin, or as some people say, then known by the name of Keemnocknagap. There was then a gentleman named Blennerhassett living at Castleconway and he, with the village folk, succeeded in getting a patent for holding a general fair on the 11th of August, all agreeing that a puck goat was the most natural and appropriate sign of which the fair would in future be known. From this small beginning Puck Fair has developed into its present dimensions and is at present the only one known by that name in Ireland or perhaps in the world.[13]

‘Certainly the fair is not one of continued antiquity … the present annual fair is the revival of one of much older standing’ – The Zetland Times, 30 September 1872

In the mid nineteenth century, the ‘goat fair’ in Killorglin was described as ‘the assemblage of the only vestige of the Gipsy tribe in Ireland,’ which suggests a Romany association.[14]

Castle Conway remained linked to the King Puck tradition as the century progressed:

The Puck Goat was placed in the centre of the town, and another in one of the last remaining towers of the old Castle Conway – the venerable ‘keep’ where centuries ago the ancestors of ‘The Conway O’Connor’ (last of his race) would prevent a goat from desecrating their home, even the very bell that hung from the puck-goat’s horns was said by many to toll the knell of Conway Castle – Sic itur ad astra.[15]

John Casey owned a billy goat, He was the Caseys’ joy, Full many a time and oft I’ve pulled His whiskers when a boy. Exemplary in all he did, With coat without a stain, We’ll never look upon the like Of Casey’s goat again.[16]

In the King Puck origins debate, ‘Killgubby’ is also named as a place of interest:

It was at the Killgubby ‘patron’ fair that the puck was first made a monarch, and that the Killorglin people having brought the fair into Killorglin they also adopted the puck and still kept him the most conspicuous object of the fair.[17]

Killgubby (Kilgubby), otherwise Kilgobnet, held its fair on 11th February.[18] In the following late nineteenth century version of Kilgubby, a description of the raising of the goat is given:

About 50 years ago there used to be a fair held every year at a place called Kilgubby, about six miles from the village of Killorglin, at which there used to be a lot of ructions and faction fighting, and three of four men used to be killed at every fair. So the priest and the parson and all the big bugs round the country decided to change the fair to Killorglin, then a small village with a few houses. There were notices posted in the six parishes stating that the fair was changed, but the country people took no notice of them but went to Kilgubby as usual with the exception of one Batt Foley, of Cloughfune who attended the new fair with a solitary puck goat. The news went abroad and everyone had a laugh and a joke about the fair but in the course of a few years the fair was really established and the young men of Killorglin used to make a collection round the country and buy the largest Puck goat they could get and get four tall poles which they put down in the ground opposite the Barrack and on the top platform in a box was placed the ‘Mountain King’ dressed in a green jacket, straw hat with green ribbons, and a bell tied to each horn, and every road coming into town had a banner across it with the following mottoes printed on them: ‘Welcome to Puck’ ‘Cead Mille Failthe’ ‘God Save Ireland’ ‘Hurrah for the Mountain King’ ‘Ireland a Nation’ etc, etc. So the old custom is preserved to the present date and the great fair of Killorglin held on the 11th August each year is known all over Europe as Puck Fair.[19]

It certainly appears that King Puck has evolved with history, and the fiery politics of the nineteenth century. The last word goes to Maurice Patrick Ryle (1868-1935) editor and founder of the Kerry People and Kerry Evening Star, and one time journalist for the Kerry Sentinel.[20] Maurice published a booklet in 1899 entitled The Kingdom of Kerry in which he included much of the above argument in a chapter about Puck Fair.[21] He concluded:

Even the oldest inhabitant cannot give a correct idea either of the date of the establishment of the fair, or as to how it really originated.

King Puck continues to hold his history firmly in the mists of time.

__________________________

[1] A second information notice gives the following: ‘Puck Fair: The first day of Puck Fair is known as ‘Gathering Day.’ The Puck Goat is enthroned on a stand in the town square and the great horse fair is held. The middle day is known as ‘Fair Day.’ This is the day of the cattle fair and general festivities. The last day is known as ‘Scattering Day’ when the brief reign of Ireland’s only King is ended and the Puck Goat is returned once more to his mountain home.’ [2] ‘The date of the establishment of Puck Fair, as well as the origin of its quaint and almost druidical ceremonial have never been definitely located’ (Kerry News, 17 August 1928). [3] Kerry Sentinel, 26 October 1898. The article concluded, ‘You can see by my last communication on this subject that the saddle is used up to our own time. It is well known that the people then and later down should employ some decoy to deceive the authorities when they wanted to celebrate any national event. This is the version of the origin of Puck Fair by Tom Fleming, an old Irish poet and schoolmaster, who was up to 100 years old when he died in 1860 and is buried in Knockane near Beaufort.’ This version prevailed, as reported in the Kerry News thirty years later (17 August 1928).‘When a party of Cromwell’s troopers made a raid into Kerry the goats browsing on Carran Tual were alarmed by the approach of the English soldiery, whose arms glistened in the sun. They rushed down the hillsides and ran wildly through the town. This unusual spectacle amused the people and being informed of the cause of it by their scouts, who did not reach the town until some time after the goats, they prepared to meet the enemy. Their stern resistance to the band of disciplined soldiers saved the village from destruction, and so thankful were the inhabitants to the goats for giving warning of the danger that they decided to establish an annual fair, at which ever since King Puck is the presiding figure.’ [4] Kerry Weekly Reporter, 10 September 1898. Repeated in the Kerry News, 17 August 1928. [5] Kerryman, 17 August 2006. [6] Translated from the Irish in the Irish Press, 14 August 1959. This article carries an image of Michael Houlihan, who had been charged with supplying the goat and erecting the scaffold at the fair for more than fifty years. [7] Cork Examiner, 9 August 1958. [8] Daily Herald, 15 August 1964. ‘It has also been suggested that the fair is also linked to pre-Christian celebrations of a fruitful harvest and that the puck was a pagan symbol of fertility’ (Kerryman, 17 August 2006). [9] Daily Herald, 15 August 1964. [10] Irish Press, 14 August 1959. ‘The decision to make a he-goat king of the fair was a subtle but unsuccessful manoeuvre by the town landlord of the period, Harman Blennerhassett, whom the English government sought to deprive of his right to levy tolls at horse, cattle, sheep and pig fairs. By the introduction of a goat fair, he succeeded in circumventing the Act of Parliament and was thus enabled to continue to collect his tolls’ (Cork Examiner, 9 August 1958). ‘Some say when the fair was first held, the only animal for sale at it was a he-goat. Certainly the fair is not one of continued antiquity though it is not improbable that the strange inauguration of the fair is traditionary, and that the present annual fair is the revival of one of much older standing’ (The Zetland Times, 30 September 1872). ‘In 1808, O’Connell was an unknown barrister. In the preceding years, the August fair held in Killorglin had been a toll fair but an Act of the British Parliament empowered the viceroy or lord lieutenant in Dublin to make an order making it unlawful to levy tolls at cattle, horse and sheep fairs. O’Connell’s legal services were called into action and he claimed that goats were not covered by the document and that the local landlord would be legally entitled to hold a goat fair and levy his tolls as usual. Thus the fair was promptly advertised as taking place on August 10th 1808 and on that date, a goat was hoisted on a stage. The tolls were collected that day and a king was born’ (Kerryman, 17 August 2006). [11] The letter in full as given in the Kerry Sentinel, 2 November 1898: ‘The following is the origin and history of the ‘Puck’ and let it be understood that I will fight through the Sentinel against anyone who will say that my knowledge of the origin of ‘Puck’ is wrong. In the years 1800 to 1808, a resident gentleman proposed to the few inhabitants of the ‘New Killorglin’ that there should be a yearly fair started so that it would commence with the ‘New Town.’ And give a chance to the poor people of the parish and ‘village.’ The inhabitants at once agreed, and were only too glad to have their little village made the place of the fair. A year had no elapsed, and the fair was not established, but towards the end of 1801 the few that composed the committee met again and discussed the matter, but they disagreed, and the idea again fell through. Three years went by and there was no talk about the fair; at length the fourth year was drawing to a close when the gentleman again tackled the ‘proposed commencement of the fair’ and at length succeeded after five years meditation on the subject. In 1806, the establishing of the new fair was published, and in six months afterwards the committee met to discuss the name of the fair. It was then proposed that a bonham, goat and calf should be placed on a raised platform, in a conspicuous place, but the committee disagreed as the trouble of hoisting these three animals was too much; therefore they agreed that the ‘puck’ would be the most picturesque, as he was also the king of the mountain animals, and the parish of the ‘New Killorglin’ so poor that the goat was the commonest and most highly praised by the people at that time; also, we read that the goat was held in great veneration by the Druids. Another reason why they agreed that the ‘Puck’ should be put on an exalted stage, was because the goat was the first animal that was driven into the first fair. The first fair held was not very well attended, while the goat was in his crib on a platform about ten feet high and a green flag waving over his head. This fair went well enough, but there was a vast difference in the next fair. On the 1st of July 1808, twenty days before the fair (which was held on 21st, 22nd, 23rd) the committee met again and decided to have ‘The Mountain King’ well rigged out for the coming fair; so they agreed to subscribe, but not having enough, went about the country, and in some places were offered potatoes, cabbages, etc, which they sold and the money used for the proper rigging out of the ‘Goat.’ They also employed a few good ‘pipers’ and other musicians who were placed beside the ‘Puck’ and beside them again was a couple of buckets of ‘poteen’ flanked by a couple of dozen of ‘yellow meal cakes’ while above the ‘Puck’s’ throne, floated flags of all nations under the ‘Green Flag’ while the old zig-zag poles were decorated out with the mountain heath, and from the centre hung a big bunch of heath and the following greetings – ‘Erin go Bragh’ and ‘God Save Ireland’ and ‘Welcome to All’ and ‘Hurra for the Mountain Prince.’ The third day of the fair ended, the goat being let down with a rope and covered with a green cloth, and a youth dressed in a red-coat and a high hat made out of the mountain heath, lead him about the fair, headed by the musicians and the highest gentlemen in the place, the whole scene being one of enjoyment and merriment. I defy any person to correct the above, or I would be glad to dispute the history through your publication; also, I would be glad to receive corrections on this history of the poor ‘Puck.’ I will prepare a ‘History and Origin’ complete to this year. I am commencing it already, and can also give the name of the gentleman who first started the fair. Yours obediently, Centurian and Patriot.’ [12] Kerry News, 17 August 1928. ‘Mr Batt Dwyer’s own version, which he took a good deal of trouble to compile by many interviews and researches throughout the district, has the verification of Mr Thomas T Foley, ex-MCC, of Anglout, who is the present Baron of the fair and in whose family those rights have been handed down for many generations. Mr Dwyer states that the people of Killorglin district, with those of every Catholic district in the country, resisted to the fullest the imposition of the Protestant Tithe tax, whereupon the title-gatherers and bailiffs swept their stock from the mountains. After a big ‘round up’ the bailiffs arrived one evening at the ford where Killorglin’s substantial bridge now stands. While endeavouring to force a large seizure of mixed animals across the river, a huge ‘Puck’ goat broke away and naturally faced back up the mountain. His example was quickly followed by the rest of the herd, and the bailiffs, being too exhausted after a long, hard day’s work to attempt a recapture, resumed their journey to Tralee with but a very meagre haul from the people of Killorglin. It was a ‘Puck’ goat that defeated the seizure, and in fitting celebration of this achievement, the most presentable representative of the species, on each anniversary day, was bedecked and beribboned and hauled to the top of Castle Conway, the ruins of which may still be seen at the rere of Sheehan’s licensed house, close to the Carnegie Hall. Thus, it will be seen that there exists much diversity of opinion as to the origin of ‘Puck Fair but though its escutcheon may not be clearly defined there remains no doubt regarding the enjoyable nature of the event, and the atmosphere of goodfellowship which intermingles with its spirited business operations at the present day.’ In the years that followed the Tithe War, there was concern that the fair would not take place. The following was reported in the Kerry Evening Post, 2 August 1843: ‘An application has been forwarded from the inhabitants of Killorglin to the stewards of the Killarney Races, not to have any race or stag hunt on Friday the 11th inst, that being the day on which the celebrated Puckane Fair is immemoriably held; and on that day there are two plates to be run for. To this request, it appears, most the stewards have acceded, and it could be wished that the consent of all was obtained, as it never was, I am sure, the intention of the projectors of the sport, that it should interfere with private property, or be attended with any public inconvenience … the fair of Puck, has at all times in this county been well attended. On the day on which the fair was held last year, there was no Magistrate present, though there was no race at Killarney that day, only a stag hunt which destroyed the fair, and if the same consequences resulted from the absence of a Magistrate there that ensued at the last fair of Molahiffe, I am sure the stewards would regret it.’ [13] Kerryman, 24 August 1912. [14] Freeman’s Journal, 18 August 1845. ‘The Lord of the Glencar mountains is led forth, through the oblong village and its dingy environs, followed by all the gypsies, tinkers, pedlars, pickpockets, and such characters who are most regular frequenters of this frolicsome fair’ (Cork Examiner, 17 August 1846). ‘With the exception of the goat and the tinker, Puck Fair does not differ much from any other provincial Irish fair’ (The Zetland Times, 30 September 1872). [15] Cork Examiner, 17 August 1863. The following description of Puck Fair was published in the Kerry Evening Post, 13 August 1873: ‘This celebrated fair was held on Monday and was well attended. As usual King Puck was elevated and was brightly dressed for the event. Near the ruins of Castleconway a green flag floated and other buildings had the red, white and blue floating over them. The full quota of thimble-riggers sporting wheels of fortune attended. The tinkers are becoming scarce of late, only a few regulars put in an appearance. The publicans did a roaring trade, Butler and Co being in great demand though some preferred a wee drop of Jameson’s. The small dealers made a good thing of mutton pies at twopence each. Daniel Dwyer says they can make choice gravy for the pies by stirring boiling water with a twopenny candle. The fair was considered dull. Several English buyers said the quality of the horses was bad. Mr Casey of Cork bought eight horses at prices from £25 to £40 each. The cattle fair was not good, the best price got for yearlings was 10 guineas. Mutton was high. I saw two fat sheep bought by Tuohy, a Killorglin butcher, for £5. Beef cows were scarce. Up to the time of posting there has been no fighting though a few were “on it” early in the day. Some gentlemen from Killorglin were examining horses all day, but did not purchase any. Another gentleman present said they knew as much about horses as the horses knew about them.’ [16] Elegy on a Goat by Microbe Joshua Queerfellow Esq (from the Buffalo Union, published in the Cork Examiner, 2 June 1894). [17] Kerry Sentinel, 26 October 1898. ‘Killgubby ‘patron’ was held on the 11th of February, a large fair being held, also on the same day. The ‘patron’ is I presume still held there but the fair is a memory of the past. A friend has also told me that the fair and ‘patron’ were in full swing when the ‘boys’ passed, marching from Iveragh towards Killarney only to learn on the way that the ‘rising’ was discovered and that no friends would meet or join them on the march. Another friend to whom I mentioned the reference connecting the puck with the Killgubby ‘patron’ fair says this is not at all correct. He also says that Lady Blennerhassett, Sir Rowland’s mother, established a second (in the year) fair at Killgubby which was held three days before Christmas, and that even though goats and haak were the only commodities sold at that fair, no particular puck was raised above his fellows. I am sure Octo could give us an interesting account of this ‘patron’ and would have mentioned it if the puck was connected with that fair.’ [18] ‘Gobnait, sometimes Gubby, and sometimes Abbey, is a pretty general name for women in my native parish. Indeed popularly Kilgobnet is called Kilgubby. Within my own recollection a great ‘pattern’ used to be held there on February 11th’ (Irish News, 16 June 1909). ‘Killorglin Weekly Market. You should not be at all surprised if our report of this day’s market is what your readers may call slack, when they consider that it is held on the day after the celebrated Kilgubby Fair. At this season we have little in fact nothing to say about butter or buyers’ (Southern Reporter, 18 February 1862). [19] Constabulary Gazette, 2 September 1899. [20] Maurice Patrick Ryle, husband of Bridget Myles, died at 3 Garden Vale, Athlone on 8th April 1935 where he had been editor of the Westmeath Independent and the Offaly Independent. His remains were returned to Tralee and he was laid to rest in Rath Cemetery. The Census of Ireland (1911) shows that he had a large family, Denis T Ryle, Mary A Ryle, Maurice J Ryle, Kathleen Ryle, Christopher Ryle, Bridget Ryle, Patrick M Ryle, Roma M Ryle, Norman C Ryle. Chief mourners at his funeral were his widow, Mrs Ryle, Jack, Colm, Pat and Tom (sons), Mrs W Netley, Mrs G O’Brien, Bridie, Roma (daughters), Thomas and William (brothers), Mrs J Ryle (daughter-in-law), Mr W Netley and Mr G O’Brien (sons-in-law), and nephews and nieces. See obituary, Kerryman, 13 April 1935. [21] Revised edition published 1902; chapter on Puck Fair in this edition pp39-49.