Collected Essays of Con Houlihan

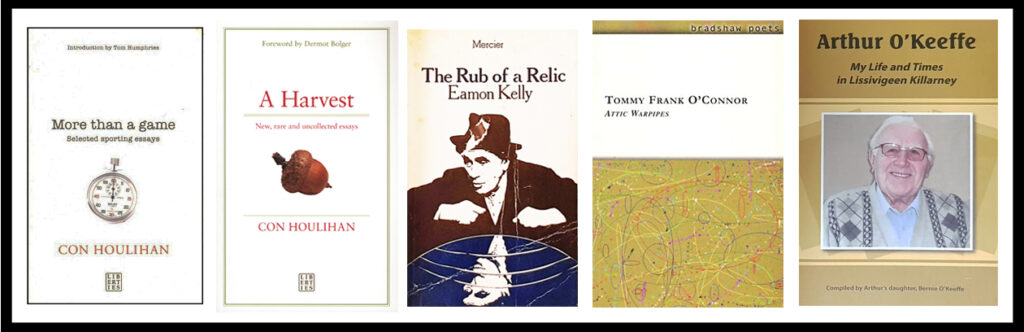

More than a game Selected sporting essays (2003), which includes the article ‘Knocknagoshel has its own Place in Racing History,’ and A Harvest New, rare and uncollected essays (2005, 2007) by Castleisland’s Con Houlihan number among recent literary donations to Castleisland District Heritage.[1]

The books contain reproductions of Con Houlihan’s essays from the Evening Press, Magill Magazine and Sunday World in the 1970s and 1980s. A Harvest alludes to his sentimental description of his departure from Castleisland in 1973 to take up journalism in Dublin. He describes his last day working in the bog with his father:

At about six o’clock we raked the embers of the fire together and quenched them with whatever water we had left over and with the tea that remained in the kettle. I was pierced with an infinite sadness. I always say there are three sad words in any language: ‘The last time.’

Before his move to Dublin to join the Press Group as a columnist, he had edited The Taxpayers’ News, a Castleisland newspaper[2] and contributed to The Kerryman newspaper in the 1960s. He made an art form of sports writing and won a readership even among those who had no great interest in the subject.

He wrote the script for the film, The Wheels of the World (1974) narrated by Eamonn Keane, much of the filming done in the Castleisland district. He was selected Kerry Person of the Year in 1985.

Con Houlihan’s accomplishments moved Jerry Daly, Caherslee, Tralee, to capture them in verse:

Now Shakespeare was a playwright supreme,

Ne’er again shall we see his like it would seem,

’Twas many the Gael that could pen something new –

Behan, Shaw and John B, to name just a few.

But newspaper writing is a special skill,

It takes someone unique to fit the bill,

And Ireland’s top scribe is a true Kerryman,

Castleisland’s own scholarly Con Houlihan.[3]

Further reference, Dictionary of Irish Biography, ‘Houlihan, Con’ contributed by James Quinn.

The Rub of a Relic by Eamon Kelly

‘A genuine 24-carat Kerryman’ – John B Keane

The Rub of a Relic (1978) records Eamon Kelly’s third storytelling evening presented by the Abbey Theatre at the Everyman Theatre, Cork on 9th January 1978.[4] It contains thirteen stories, and a flavour of content is given in the tale of teenager Ned Connor who, after a row with his father, leaves home in the middle of the night ‘in the general direction of America.’ Ned arrives next morning at Cromane Pier.

There he boards a small fishing boat with instructions to the fisherman to take him to Boston. Having been gently let down, Ned is advised by the fisherman to go to Tralee and join the Munster Fusiliers. He duly signs up, his first week’s pay being spent in the pub. After a heavy drinking session, he misses his turn to the barracks in Ballymullen and ends up on the road to Castleisland where he strips off and falls asleep by the side of the road.

Awoken by the cold, and having lost his uniform in the dark, he calls at a nearby farmhouse for a loan of clothes where there happens to be a wake in progress. The corpse almost scares Ned to death when it shows signs of life and he discovers it is no more than a suspicious husband feigning death to catch out his wayward spouse. Ned leaves all the drama behind to go and fight in the Boer War in South Africa.[5]

Eamon Kelly, master storyteller, was born near Rathmore on 30 March 1914, and grew up in Carrigeen, Killarney. The Kelly home was a rambling house with no shortage of material to fill the repertoire of the future seanachai. He left school at age 14 to help his father Ned, a builder. He attended Killarney technical school part time to train as a woodwork teacher, working first as a travelling teacher until he gained a full time post in Listowel.

There he met Bryan MacMahon, founder member of Listowel Drama Group, and ‘began his journey towards theatrical fulfilment.’[6] He also met Maire O’Sullivan, who played Pegeen Mike in The Playboy of the Western World. They subsequently married and joined the Radio Eireann Players where they worked for twelve years. In line with this, Eamon was developing his storytelling talent and became a regular on programmes such as Balladmakers’ Saturday Night and The Rambling House.

In 1966, he was nominated for a Tony Award for his role in the first production of Brian Friel’s Philadelphia Here I Come.[7]

Eamon Kelly died in a Dublin hospital on 24 October 2001. The funeral service was held at St Brendan’s Church, Coolock, Dublin, and he was buried at Fingal Cemetery, Balgriffin.

Eamon Kelly was survived by Maire and children Eoin, Brian and Sinéad. Further reference, Eamon Kelly The Storyteller An Autobiography (2004).

Attic Warpipes by Tommy Frank O’Connor

Attic Warpipes (2005) a selection of poetry by the late Currow born writer, Tommy Frank O’Connor – ‘Clan File of the O’Connor Kerry clan’ – has been added to the archive of Castleisland District Heritage.[8]

Among the sixty compositions, two are in memory of Sliabh Luachra fiddler, Patrick O’Keeffe (A Master’s Rest and A Scent of Music). Another, Blasket Flight, records the evacuation of the Blasket Islands in November 1953. Listen to the Light captures the signing of the Northern Ireland Peace Agreement Good Friday 1998.

In 2003, Tommy Frank O’Connor was a close runner-up in the Cork Literary Review/Bradshaw Books Poetry Collection Prize with Attic Warpipes. It was recommended that the collection be published.[9]

Tommy Frank O’Connor, whose other works include the novel The Poacher’s Apprentice (1997), was the eldest of ten children of Tommy and Ellen O’Connor. He attended St Brendan’s Seminary, Killarney and subsequently studied for the priesthood at All Hallows College and St Patrick’s College, Thurles but later questioned his vocation. He went to London to study accountancy where he met his future wife, Sheila Spelman. They married, returned to Ireland and raised a family of five. Frank later set up an accountancy practice in Tralee.

Tommy Frank O’Connor, who always remained devoted to the church, died at University Hospital Kerry on 19 October 2016. He was buried in Rath Cemetery. Further reference, obituary, ‘Writer at the heart of community life,’ Kerryman, 14 December 2016.

Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times

My Life and Times in Lissivigeen Killarney (2019) compiled by Bernie O’Keeffe is a memoir of the late Arthur O’Keeffe (1921-2020) of Fort William House, Lissivigeen, Killarney.[10]

Arthur, who was encouraged to write his memoir by his grandson, Conor Coakley, recalls how his grandfather, Arthur Thade O’Keeffe of Raenasup, Gneeveguilla, made his money in the goldmines of Ballarat, Australia.[11] This enabled him to return to Ireland in the late nineteenth century to buy a farm:

When Arthur Thade eventually left Australia for home, he had all his money in a leather money belt tied around his waist next to his skin and he had to keep it there for the six months journey home. My father told me that the welts from the money belt were on his father’s body until the day he died.[12]

The farm was later divided between two of Arthur Thade’s sons, Owen and Daniel. Owen’s half included Fort William House:

The first family to live in the house were named Dumas from Fort William in Scotland, hence the name. I presume they were rent collectors or agents of some sort for Lord Kenmare. I know they later returned to live in Scotland … Fort William House is now a listed house.[13]

Arthur, son of Owen, was the eldest of four, his mother Hannah O’Sullivan of Faha.[14]

After a brief spell in second level education, Arthur took up full time farming with his father, describing the work as ‘slavery and drudgery.’

In 1936, he participated in the filming of The Dawn, and alludes to the movies when he reflects on outings to shoot deer:

It was an offence to shoot deer then … we felt like outlaws with our guns like in the Western films we used to watch.[15]

He joined the LDF (Local Defence Force) during the Second World War and considered joining the British army but his mother found out and her upset caused him to abandon this plan.

In 1949, with other local farmers, he constructed a Macra Na Feirme hall (using a dismantled dance hall from Milltown) in Lissivigeen – the first to build their own hall. Arthur discusses farming practices of pre-1960s, such as threshing, stooking, crushing, and the introduction of modern farming practices.

Indeed, Arthur’s scope is wide; he discourses on politics from the founding of the State, the dance halls, old folk traditions on the calendar, the banshee, piseogs, fishing. He recalls the introduction of electricity, his first car and driving in the 1950s, the importance of radio as entertainment, like The Kennedys of Castlerosse, a lunch time play that ran for almost twenty years from 1955; the background of the Lissivigeen Group Water Scheme (1960) ‘the first in Ireland.’

Space is given to Lissivigeen GAA:

I have very happy memories of playing in a field at White Bridge, next to the Flesk River, which was very kindly donated to us by Major Anthony MacGillicuddy who owned the Flesk Castle. It was a lovely flat field where we had many great matches. He used to come to all the matches and brought a gaming machine with him like the one armed bandits they have in the bazaars. He donated the money he made from it to the club.[16]

He reflects on religion:

I would not have allowed myself be railroaded into doing what we did without question or choice … I think I would like to make up my own mind having first considered matters carefully. In more recent times, we have seen that the religious hierarchy have not always done the right thing in important matters and I believe the power they exercised over us in my younger days was unhealthy. They had too much power over us.[17]

Arthur married Kit Buckley in 1955 and they had three children, Bernie, Noel and Geraldine. Approaching his 88th birthday, Arthur mentioned to his daughter Bernie that he would have loved to have travelled to the places where his ancestors went during hard times, and regretted not having been in an aeroplane.

A plan was rapidly put into place, and a small private plane organised at Farranfore to take Arthur for his maiden flight around Killarney and Lissivigeen, ‘an experience I found truly wonderful.’ Arthur enjoyed singing and in 2011, a CD, Arthur O’Keeffe Sings Some of his Favourite Songs, was produced to celebrate his 90th birthday.

Comparing the old way of life to the modern, ‘in having, and in not having,’ Arthur lamented that the old custom of visiting neighbours – ‘a welcome change from all the drudgery of work’ – and storytelling as entertainment came to an abrupt end in the 1960s with the coming of television:

Everyone stayed at home to see the black box and they are still looking at it today sadly.[18]

Overall, Arthur recognised the spirit of the meitheal in community groups like Tidy Towns and tasked the next generation with developing their wider benefits.

Arthur Eoin O’Keeffe died on 19 December 2020, having lived for almost a century. He was buried in the New Cemetery, Killarney.

________________________

[1] IE CDH 53 Donated by John Roche. [2] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/con-houlihan-and-the-taxpayers-news/ [3] Evening Press, 9 December 1993. See same for verse in full. [4] IE CDH 53. [5] ‘The Effigy,’ The Rub of a Relic, pp41-51. [6] Kerryman, 1 November 2001. [7] Obituary, ‘Storyteller Eamon Kelly dies aged 87,’ Irish Examiner, 25 October 2001. [8] Donated by John Roche. IE CDH 53. [9] Kerryman, 18 December 2003. His prizes for writing include The Francis McManus, The Kerry International Summer School, The Jonathan Swift, The Cecil Day Lewis, Crann 2003, Tavistock and Athlone. See obituary, Kerryman, 14 December 2016. [10] Donated by Marie, daughter of Eugene O’Keeffe, a brother of Arthur. See Happy Days: Reminiscences of a Kerryman on the website of Castleisland District Heritage: http://www.odonohoearchive.com/happy-days-reminiscences-of-a-kerryman/ [11] The O’Keeffe family tree is given on pages 4-11. Arthur Thade O’Keeffe (1839-1914) married Mary McGillicuddy, Coolbane, Killorglin and they had eleven children: Thado (born 1879) emigrated to New Zealand; Denis (1881-1939) emigrated to South Africa; Autie (born 1884) emigrated to New Zealand; Owen (1888-1967); John (born 1889) emigrated to New Zealand; Daniel (born 1891) married in Ireland to Hannah O’Sullivan of Minish; Pat (1895-1913); Tom (born 1896) went to UK; Cissie (Mary) 1882-1932; Kathy (born 1886) married Mike Cronin; Ellie (born 1893) emigrated to New Zealand. [12] Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times, p5. ‘He was interested in buying a farm with his money. Lord Kenmare owned a farm in Lissivigeen and my grandfather took it over, paying rent to Lord Kenmare … He took over the farm in May 1879 and the rent was £8 per annum. In later years, the rent was halved. I still have the rent book from 1879 to 1902.’ [13] A record of Fort William House is given in Valerie Bary’s Houses of Kerry. [14] His siblings were Thado 1922-1927, Maunie 1923-2012 and Eugie 1926-2022. See http://www.odonohoearchive.com/happy-days-reminiscences-of-a-kerryman/. The ancestry of Hannah O’Sullivan, who died in 1960, is given on pages 11-13 of the memoir. Her sister Nora married Mr O’Hanlon from Castleisland. [15] Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times, p46. [16] Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times, p37. In pages 70-73 Arthur recalls travelling to All Ireland matches. [17] Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times, pp55-57. [18] Arthur O’Keeffe My Life and Times, p59.