Sylvester Poff and James Barrett were tried twice at the Munster Winter Assizes of 1882 for the murder of Thomas Browne of Dromultan. At the end of the first trial, which took place on 14 and 15 December, it was shown that there was ‘not the slightest chance’ on the jury agreeing. The following week, on 20-22 December, a second trial took place at which Poff and Barrett were found guilty by a ‘special jury panel.’

On 9 July 2021, the TV documentary series, Murder Mystery and My Family screened the story of Poff and Barrett. Two UK barristers, Sasha Wass QC and Jeremy Dein QC, revisited the case and put their findings before high court judge, David Radford, who found the convictions of Poff and Barrett unsafe.

On 16 December 2021, Castleisland District Heritage submitted application to the Department of Justice for the Posthumous Pardon of Poff and Barrett.[1] Currently, the file is with a member of the Department’s Strategic Policy, Planning and Research Team for processing.

The arrest and conviction of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett occurred early on in the period of land agitation that began in 1879. Scottish barrister Alexander Innes Shand in his Letters from the West of Ireland, published in 1884, recalled the condition of Ireland up until then:

It must be remembered that till the commencement of the land agitation, whatever might be the feelings of the tenants towards their landlords, there had not been a single murder in Kerry; and six policemen, for example, used to suffice for the barony of Castle Island where now there are no fewer than sixty.[2]

The executions of Poff and Barrett would add to Castleisland’s emerging reputation as the murder capital of Ireland. John Adye Curran QC, a judge in Kerry during the period 1886-1891, described the town as ‘a scandal, not only to Kerry but the rest of Ireland.’[3]

As Poff and Barrett endured a system of punishment for agrarian crime in its infancy, things would be no better for John Twiss, who suffered the same fate twelve years later.

Justice Sought for Poff and Barrett

In December 2021, John Twiss was officially Pardoned, and the record set straight on the shortcomings of nineteenth century investigation and litigation in this case. It is hoped that the same can be achieved for Sylvester Poff and James Barrett, and that their descendants can have the stain of murder removed from their family histories.

The 1882 trials of Poff and Barrett are transcribed below; the horrors the men faced in the courtroom as their lives were carried on the backs of their legal representatives must be left to the imagination. The conviction of murder sought by the Crown was not achieved at the first trial, and so a second had to be endured. On this occasion they were convicted, petitions for reprieve denied, and they were sent to the gallows to hang side by side for a murder they did not commit.

The people responded by keeping the wronged men alive in their stories and their songs; the miscarriage of justice would not be subdued by time or punishment, the people would remember. The injustice would transfer from one generation to the next until it would be heard, until the authorities would listen and concede that Poff and Barrett were victims of a system that failed them.

This collective cry is heard in songs of the period, one of which, the Poff and Barrett Ballad, was composed in the aftermath of the two trials.[4] The words perfectly encapsulate the experiences of the men as shown in the transcription of trials below.

Richard Prendergast of Keel, Castlemaine, whose song John Twiss of Castleisland appears on his CD, Songs from the Past, has put the Poff and Barrett Ballad to music for Castleisland District Heritage.[5] Please click the link below to listen.

Poff and Barrett Ballad

Come on you lovers one and all,

And listen unto me,

A mournful execution that happened in Tralee.

Poff and Barrett met their doom,

May heaven be their bed,

Their dying declaration –

These are the words they said:

James Barrett says: “I do declare

Before my God and Judge

That I never injured Thomas Browne

Or owed him any grudge.

I was not in the field that day

The fatal shot was fired,

Nor never knew the deed was done

Till after he expired.

I am a young man in my bloom,

I am scarcely twenty-five;

I never injured any man

As long as I’m alive.

In youthful days of manhood

I must give up my life,

Into the Blessed Virgin’s hands,

Who’s Mother, maid and wife.

God help my two young sisters

Who witnessed so much grief,

God comfort my poor parents

And grant to them relief.

Good-bye to all my dearest friends

Around my native place,

And when my spirit is at rest

Don’t throw me in their face.”

Sylvester Poff next handed,

The priest being in his cell,

A folded slip of paper

His dying words as well.

“Now I’m going before my God

Upon this very day;

I never injured Thomas Browne

Or took his life away.

There is one request I have to ask

Before I end my life,

I have a helpless family,

Likewise a loving wife.

I hope you won’t forget them

When I am in the clay

May the Lord have mercy on our souls,

That is all I have to say.”

Like soldiers bold they soon ran up

The scaffold grim and high,

You’d think that they were anxious

To know who first would die.

Their moments they were numbered

Before the trap did fall,

And turned around again once more

Those words addressed to all.

“We now confess before our God

Who reared us from our birth,

That we never injured any man

Or woman on this earth.

May the Lord have mercy on our souls

And we hope each one will pray

Unto the Blessed Redeemer,

To wash our sins away.”

Transcription of Trials of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett

First Trial

Munster Winter Assizes

Tuesday 12 December 1882

Sylvester Poff and James Barrett were arraigned for having, on the 3rd October 1882, near Castleisland, feloniously, wilfully and with malice aforethought, killed and murdered one Thomas Browne.[6]

Poff, on being asked to plead, said – I did not murder him no more than any man in court.

Barrett pleaded not guilty.

His Lordship – Are you both ready for your trial?

Barrett – We want counsel to defend us, my Lord.

Mr M J Horgan, solicitor, Tralee, said he had been concerned for the prisoners at the preliminary investigation and he had made out briefs for counsel at his own expense.[7]

His Lordship – Oh very well.

M Horgan said the case was a serious one and he would wish to have two counsel assigned for the defence.

His Lordship – I am afraid I have no power to do that.

Mr De Moleyns QC – The Treasury would not pay for two.

Mr Horgan – Then I would wish to have Mr D B Sullivan assigned as counsel.

His Lordship – Very well.

Mr De Moleyns QC – The case will be tried on Wednesday.

The prisoners were then put back.

Mr D B Sullivan said he had been assigned as counsel for the two men Poff and Barrett, charged with this murder, the hearing of which had been fixed for Wednesday morning. Having looked into his brief he had come to the conclusion that it would be impossible for him to be prepared for the following morning in the absence of a map of this locality which was essential to the defence of the prisoners.

His Lordship – Have the Crown a map?

Mr O’Brien QC – We will have a map by and by, and if your Lordship thinks we should give them the map, which is portion of the evidence for the prosecution, we certainly will.

His Lordship – You ought. Otherwise they must get time to get a map themselves.

Mr O’Brien – If your Lordship says so we will do it.

Mr Sullivan – What we want is a tracing – when can we have it?

Mr O’Brien – You will have it before eight o’clock this evening.

Mr Sullivan – That will do. We will be ready in the morning.[8]

[The trial seems not to have commenced on Wednesday 13 as indicated but on Thursday 14]

Day 1: Thursday 14 December 1882

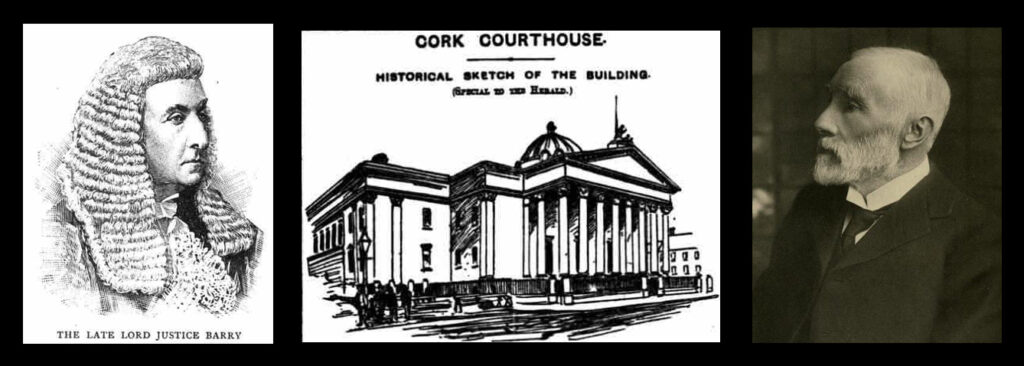

Justice Barry sat in the Munster winter Assizes.

Sylvester Poff and James Barrett were indicted for the wilful murder of Thomas Browne at Dromultin, near Castleisland, on the 3rd October last. The prisoners pleaded not guilty, and were defended by Messrs D B Sullivan and George Lawrence (instructed by M J Horgan, solicitor, Tralee).

Mr De Moleyns QC and Mr Peter O’Brien QC (instructed by Mr A Morphy, Crown Solicitor for Kerry).

The following jurors (the special panel being called over on fines of £20) were ordered to ‘stand-by’ on the part of the Crown – Messrs P Moore, P D Hogan, Simon Bowen [or Browne], Wm Walsh, Richard Lombard, David Saunders, Wm Ross, John Power, Patrick Cronin, John Richardson and Daniel McCarthy.

The following were challenged on behalf of the prisoners – Messrs Michael Russell, Wm Moore Hodder, Thomas B Montgomery, John Hannan Thomson, Wm Welland, Samuel Anglin, Francis Sergeant, Wm Wheeler, George Lamb, Henry Smyth, and Samuel Baker

The following were sworn as a jury : – Messrs Wm Walton (foreman), T D O’Brien, David Barry, James Adolphus Fitzpatrick, A B Cross, James O’Mahony, John Daly, Robert Fitzgibbon, Wm McCormack, James Scanlan, Francis W Allman and John Leader.

Mr De Moleyns QC in stating the case for the Crown said he was sure it was almost needless to ask their earnest and careful attention to a case like the present, involving issues so grave and the importance of which cannot be overestimated. In all those cases they all had separately their respective duties to perform – all to a certain extent painful and responsible, and they could not allow and should not allow any morbid statement to interfere and prevent them from doing their duty. Their duty in that and in all other cases would be to form a conscientious opinion on the evidence brought before them, and he (counsel) would not press anything or state anything that did not bear legitimately on the issue they would have to try. The prisoners were charged with the murder of a man named Thomas Browne on the 3rd of October last, at Dromultin, near Castleisland, Browne appeared to have been a large farmer, industrious, hardworking, and bearing a good reputation; but he was something more than a farmer. He held, in common with two other tenants of the name of Fitzgerald, a large farm, and was able to purchase the fee of it some years ago for the sum of £1,500, thereby becoming his own proprietor as well as the landlord of the other tenants. On the morning of the 3rd October last he had gone into Castleisland, and returning on his way home through Scartaglin he went into the house of a publican named Leary, where he saw the two prisoners and a man named John Dunlevy, to whom he would have to call their particular attention. He might now state that Dunleary (sic) had left the country and was not forthcoming; but he was in their company at that time, and at an antecedent period. He would now give them a record of Browne’s movements in the first instance on that morning. The prisoners and Dunleavy had been drinking in the public-house on that morning and Browne, who was there also at the time, left before them about one o’clock, and went to work for some time on one of his meadows. Soon after he went to his dinner, and returned to work again to the same field, the one in which he was found murdered, at an hour which would be fixed as a quarter past four. He would now call their attention to one of the witnesses to be produced by the Crown – a woman named Bridget Brosnan. She lives near Browne’s house – a respectable woman, who earned her livelihood by performing little jobs and to whom Browne and his family had been always kind, and she felt a corresponding feeling for them.

Her house was also close to that of a man named Patrick Fitzgerald. About half-past eleven o’clock on that morning she saw the two prisoners, accompanied by Dunleavy, passing her house and she spoke to them on their way to Scartaglin. They (the Crown) would be able to trace the three men to the public house of Leary, where they remained from eleven o’clock until a little before three o’clock. In the evening at about ten minutes or a quarter to four – the time would be specifically fixed, Mrs Brosnan went out of her house to gather a basket of rushes in the dyke close to the fence on the opposite side of the road bounding Brosnan’s farm. The meadow in which Browne was working was separated from the road by an intervening field about 80 yards in breadth, and when a map would be produced they would find that nearly opposite the field where Browne was murdered was the house of a woman named Ellen Fitzgerald. Having got the rushes after a few minutes she got up on the fence, which was about three feet high, for the place where she had been getting the rushes was upon the opposite side of the road from the fence from which bounded Browne’s farm. She had to get up on the ditch to go down to her own house, and he might mention that this place is somewhat elevated and commands a view of the country round. Just as she got up on the ditch she saw two of the men whom she had been speaking to in the morning, and whom she well knew, approaching her from Ellen Fitzgerald’s house, two men being prisoners; the two men having reached a spot convenient for the purpose turned to their left, jumped on to the fence, and went into the field adjoining the one in which Browne was working, and in which he was in a few minutes afterwards found murdered; she would swear positively to those men; knew them well, and had spoken to them on that morning; there were no persons in sight, and she would swear to them two men; and there was no reason to doubt her accuracy or interest in the question, were the prisoners at the bar; alarmed by what she saw the men do, probably alarmed by other matters, what had already happened in the district – possibly also some of those mischievous rumours which circulate through the country – alarmed, however, at what she saw occurring, she hurried down to Browne’s house, a distance of about 180 yards; saw Mrs Browne at the gate; told her what she saw, and urged upon her as much as she could, to go into the haggard and see what was going on; she went out in an alarmed and excited condition, suspecting what the men wanted to do. So far, he (counsel) brought them to the spot of the murder; a boy who actually saw the murder take place, would also be produced, and they (the Crown) charged that the two prisoners being thus brought together to that spot and shots being heard at the same instant – several shots being also heard by Mrs Browne and Mrs Brosnan and the boy – the men being identified by one witness, and seen by another to commit the murder – they charged that the two prisoners committed this dreadful atrocity. These were the material facts of the case. The two men were arrested shortly afterwards and were brought up before the magistrates at Tralee on the 19th of October and before being conveyed back to the gaol after the investigation, the prisoners, with their escort, were placed in a room pending some preliminaries which should be complied with. In that room a scene occurred, which would be detailed to them in evidence. One of the constables, who was in charge, had his back turned to Poff and Barrett, who were sitting close together, Dunleavy being within three yards of them. The constable overheard a conversation – a statement made by Poff to Barrett in reference to Dunleavy. That statement, he had thought it better, and fairer to the prisoners, not to state himself, but would get it from the lips of the person who overheard it, and if he (counsel) was not mistaken they (the jury) would think it of considerable significance. His statement would be clearer when the map of the locality was produced and explained. He had only to say, in conclusion, that he trusted, if they were satisfied with the evidence of those facts, that they would give a verdict which the interests of justice and their own duty to their consciences, and to their country, would require.

Evidence was then gone into.

Mr Robert Denny, CE, was the first witness examined, and he produced the map referred to in the statement of Mr De Moleyns.

Bridget Brosnan, examined by Mr O’Brien QC on being sworn.

The Prisoner, Poff – Make her kiss the book.

His Lordship – Did she kiss it before.

Mr O’Keeffe (Clerk of the Peace) – She did, my Lord.

His Lordship – Well, make her kiss it again.

Witness (to Mr O’Brien) – I live near the house of Thomas Browne; on the morning of the murder I saw Poff, Barrett and Dunleavy were on the road near my house; I knew them well; they were going that morning in the direction of Scartaglin, and I told Poff that last winter Dunleavy threw a bucket of water and dung down on me in the kitchen; later in the day I saw the post-boy, Mahony, pass, and then I went down for a little rushes, down into Browne’s fields; I turned at Browne’s house and went towards the field where there was a little hollow; I was about two minutes cutting the rushes and got upon the fence to come home, and as I got on the fence I saw Poff and Barrett coming towards me; they leaped over the fence and faced up to where Browne was working; I then ran up to the gate to Mrs Browne and said there were two men gone into the field; ‘They are men coming from the funeral,’ said Mrs Browne, and as she said that I heard the shot. ‘Oh Lord,’ I said, ‘he is shot.’ ‘They are fowlers,’ said Mrs Browne; the shots came from where I saw Poff and Barrett go down; I went home myself with the rushes and then brought a gallon of water and saw Browne’s daughter crying. I asked what was the matter, I knowing it very well, and she said, ‘My dad was shot just now.’ I saw Barrett lying on the top of the ditch, near this place a fortnight ‘ganging’ there; after that I made a communication to Thomas Browne.

Cross-examined by Mr O’Sullivan – Barrett lives close to me on the same road; I could not say whether Poff had his dog with him that morning; I didn’t ask Mrs Browne who the men were when I went up to her at the gate with the reaping hook; I told her three men went into the field; I mean two; I never swore before that three men went into the field; I was examined at the inquest and stated at that time that Poff and Barrett went into the field; I swore it there because I was in dread of my life. Now, didn’t you swear also at the inquest that three men went into the field? I don’t say they did; I was trying to save them.

Mr O’Brien – There were no depositions at the inquest.

His Lordship – Why not?

Mr O’Brien – I don’t know. Perhaps your Lordship would direct an inquiry into that. There may be reasons which I would state before your Lordship.

His Lordship – Very well. Let the Crown move in the matter.

Witness (to Mr O’Brien) – After the inquest I went to Confession to Father Scollard, and that was the reason I changed the evidence. He told me –

Mr O’Brien – You can’t state.

Mrs Johanna Browne, examined by Mr De Moleyns QC – On this morning my husband went into Castleisland and returned at twelve o’clock and after dinner he was working in the field at the hay; that evening Mrs Brosnan came to me pale and excited and while we were speaking I heard two shots; I went into the haggard and saw two men going in the direction of Castleisland; they had not then reached the bog; that was about 5 o’clock.

To his Lordship – They appeared to be running.

To Mr Lawrence – There was a funeral in the neighbourhood that day; Mrs Brosnan asked me when she came up to go and see who were the men in the field. Did she ask who were the men? I can’t remember now, I am not able. Did you say they were fowlers? I said so, and Mrs Brosnan said, ‘I suppose so,’ and went away then.

To his Lordship – Mrs Brosnan told me to go to the field; I thought she looked queer and frightful when she came up.

Maurice Horan, examined by Mr O’Brien QC – I am a cousin of James Barrett. I was at school the day Thomas Browne was shot and coming home from school I came near Browne’s field. On the road home I saw two men coming away from Fitzgerald’s and going towards Browne’s. They stood a little when they went into the field off the road, near where Browne was working. Browne was walking up the field towards them, and then I heard the shots. I did not see the men firing at all. I only heard the shots. I did not see Browne fall. The men were near Browne, and after the shots the men ran towards the road that runs by Ellen Fitzgerald’s. I went up to the field and saw Browne lying dead. I know Mr Considine RM. I said to him I saw the men fire several shots at Browne. I saw them fire several shots at Browne. I saw them fire.

To Mr O’Sullivan – I know my cousin well. I don’t know Mr Poff. They were dressed in black.

To his Lordship – I was not near enough to know the men.

To a juror – They were about the length of the courthouse away from me.

His Lordship – These little boys have no idea of distance.

Mr Denny, re-examined, stated that the distance between where the boy pointed out that he was standing and the scene of the murder was about 160 yards.

Dr Nolan, Castleisland, examined by Mr De Moleyns, stated – I in company with Dr Harold made a post mortem examination and found a bullet wound penetrated the bone behind the left ear, it passed through the brain and lodged under the skin under the right temple; that would be sufficient to cause instant death. I gave the bullet to the police; a second bullet passed through the chest.

Mr O’Brien –Here is the bullet, my Lord, that was found in the head.

His Lordship – A very curious effect the bone had on it; it is quite flattened.

To Mr Lawrence – My opinion is that the bullet in the body passed from the front to the back; I don’t know Dr Harold’s opinion.

Bartholomew O’Brien, examined by Mr O’Brien, stated – On the day Browne was murdered I met the prisoners and John Dunleavy in the village of Scartaglin. I went with them into Michael O’Leary’s public house; after that we went to the Post Office where we played cards; I think we left there at three o’clock, and then we went to Horan’s public house and had a couple of drinks there; there was present John Dunleavy, Poff and Barrett, a boy of the Lyons, and a boy named O’Leary; I then went into the kitchen, and after that I did not see Poff and Barrett; Dunleavy remained in the public house; I could not say it was a half an hour while we were in Horan’s; I remained there until I heard of the murder of Browne; Dunleavy was there all the time; I saw him talking to the soldiers.

To Mr Sullivan – There were a good many strangers in Scartaglin that day at a funeral from Listowel; Poff had a large black dog with him.

Michael O’Leary examined by Mr De Moleyns QC – I keep a public house in Scartaglin, and that morning Poff, Barrett and Dunleavy came into my public house; I went to a funeral and returned about a quarter to five o’clock and found Dunleavy still in town; I did not see either Poff or Barrett there.

To Mr Lawrence – Poff had a large black dog with him.

Michael Mahony examined by Mr O’Brien – I live at Farranfore and carry the post every morning to Scartaglin and return in the evening. I passed Browne’s place at a quarter to four or four o’clock that day; I did not meet anyone on the road that day.

Sub-Inspector Davis, examined by Mr O’Brien QC, stated – I am the sub-inspector of the Castleisland district; Mrs Browne could easily recognise a person at the scene of the murder from where she was standing; the boy Maurice Horan was not in the next field to the murder – he was in the second next field, and there were two fences between them; hearing of the murder I went as quickly as I could to Browne’s house and having seen the body and examined some people, I looked at the clock and was astonished to find that it was fifty minutes fast.

Mr Considine RM examined by Mr O’Brien stated – I am the magistrate who had charge of this case; I was present at the inquest; Mrs Browne did not then state there were three men went into the field.

Mr O’Sullivan – Did she state she did not know the men? She did not.

Mr O’Brien – What did she say?

Mr Considine – She said, to the best of my recollection, ‘How could I know who they were.’

On being pressed by the Coroner, she said, ‘I have told you all I know and I won’t tell you any more.’

Sub-constable Dallas, examined by Mr O’Brien, stated – On the 18th of October I was one of the escort that conveyed the prisoners and Dunleavy from the courthouse to the gaol; when I arrived at the gaol I took Dunleavy to the waiting-room, and Poff and Barrett were sitting about three yards from Dunleavy; I was sitting partly in front of Poff and Barrett, with my back turned; I heard Poff speak to Barrett and say in an undertone, ‘The smallest thing in the world would hang us, and Dunleavy could do that if he liked; but they would shoot him if he did.’

Barrett said nothing, but he made a motion to go towards Dunleavy; I then said I would not allow any talking, and Poff said in a friendly way to me that perhaps it would be no hard to let Barrett speak to Dunleavy; I told him that I was cautioned by my officer not to allow any talking, and that I could not permit it; afterwards I made a note of it (the note was here produced).

Cross-examined by Mr Lawrence – The conversation was after the investigation before the magistrates, when the prisoners were returned for trial; Constable Clarke and several constables were there at the time; it is a pretty small room; the note-book produced is the regulation note-book; I had it about a month before this occurrence. Is there not a regular notebook issued by your officer in which you must enter everything connected with your duty and keep it until it is exhausted and then you are supplied with another? There is no regulation book issued to us; we get nothing free (laughter); I wrote these words half an hour after in the barrack with pencil and afterwards I wrote over a portion of it in ink; I wrote the date, ‘19th October’ in ink.

Mr Lawrence – Did you make two other notes?

His Lordship – Is one a copy of the other?

Mr Lawrence – No, my Lord.

Witness (to Mr Lawrence) – One is not a rough draught (sic) of the other. Just look at the other entries and tell me when you made them. I can’t tell you; the first was the real entry; then the other entries are not real entries? Yes; they are.

Mr Lawrence – I will read the entries – ’19-10-82 Words used by Poff and Barrett’. Nothing follows that. Another entry was, ‘19th October, 1882, words used by Poff and Barrett, and overheard by me: – ‘The smallest thing would hang us. Dunleavy could do it if he liked to,’ and no more. The other one was full.

His Lordship – Do you swear the full one was the first entry?

Witness – Yes; the first entry.

His Lordship – And were these intended to be fair copies of them?

Witness – Yes, my Lord.

To Mr O’Brien – I made a communication that evening to Mr Holmes, my inspector, with regard to the statement.

Mr Considine RM, recalled, said that on the next day the sub-inspector made a communication to him with regard to this conversation.

Mr O’Brien said they intended to telegraph to Sub-Inspector Holmes with regard to this conversation, and he would ask his Lordship to allow him to examine Mr Holmes in the morning.

Mr O’Sullivan – I may say, my Lord, we intended to impeach this constable’s statement.

Mr O’Brien – Of course, and that is the reason we wish to have Mr Holmes’ evidence.

Poff (rising in the dock) – I would wish to make an explanation of my words, my Lord.

Mr Horgan, solicitor for the defence – Sit down.

Poff – My words were taken down by the –

His Lordship – I can’t hear you now. I will hear you afterwards.

Mr O’Brien – I would wish to ask Constable Dallas a question, my Lord.

His Lordship – Certainly.

Mr O’Brien – Did you make a communication, Constable Dallas, to Constable McGragh that evening with regard to the matter?

Sub-Constable Dallas – Yes, I did.

Mr O’Brien – Subject to that, my Lord, we now close.

The court then adjourned for half an hour for luncheon.

Sub-Inspector Davis was recalled and in answer to Mr O’Brien, produced a bottle containing some whiskey found in a ditch in the direction in which the murderers went; it was about half a mile from the scene of the murder.

Mr Sullivan then opened the case for the prisoners. He said he should not affect to think it necessary to impress on them that this was a case requiring their most careful and serious consideration. It was true that they stood in the presence of a dreadful crime, a crime closely associated with a certain social condition of things which they regarded with indignation and abhorrence. It was to men in whose ears the narrative of that dreadful murder was still ringing that he should at the outset appeal for dispassionate consideration. They might start with the melancholy fact that on that October day Thomas Browne was foully murdered by some men who, after having committed the dreadful deed, disappeared in the direction of Castleisland; the whole question for them was as to the identity of the assassins. It was to that part of the case made by the Crown that the evidence for the prisoners would be distinctly applied. And looking at the broad facts of the case, it did at first appear somewhat startling that at 4 o’clock on that evening in October, the two prisoners, undisguised, in a locality where they were well known to everybody, should commit this dreadful assassination. Cases had occurred in which the assassins were undisguised, but that was when the assassins were strangers brought from a distance. There was a total absence of proof of ill feeling between the deceased and the prisoners, and no reason suggested why the two prisoners should imbrue their hands in the blood of their friend and neighbour. He reminded them of the fact that a large funeral had passed by that place some hours before, and said it was highly improbable that any men known in the neighbourhood should run such a terrible risk. The case for the prosecution rested exclusively upon the evidence of the old woman Brosnan and her identification of the prisoners he impeached as wholly unreliable. She came before them a tainted witness, who admittedly had on a previous occasion sworn to a deliberate falsehood. The evidence of Mrs Browne, was that the assassins wore long black coats, but it would be proved that on the day in question the prisoners wore ordinary clothes, in fact ordinary grey and white frieze, worn by peasants in that part of the country. Referring to the evidence of Sub-constable Dallas, as to the statement made by Poff to the other prisoners in the waiting room of the gaol, counsel said it was the most extraordinary evidences ever given in a court of justice, and was in fact perfectly incredible, and he asked the jury to dismiss it altogether from their consideration. Having referred to the nature of the evidence to be given on behalf of the prisoners, counsel said that if it were according to his instructions the prisoners would not have to ask for the benefit of any doubt but would demand a triumphal acquittal at their hands.

The following evidence was given.

Mrs Browne, recalled by his Lordship, said that Mrs Brosnan did not tell how many men were there.

Mrs Brosnan, recalled by his Lordship, stated that when she saw the prisoners that morning they were dressed in their everyday clothes, just as they wore in the dock; they were dressed in the same manner when they entered the field.

A Juror – When did she give the names of the men first?

His Lordship – When she made her information. At the inquest she said that she did not know the men.

Mrs Brosnan – Yes, my Lord, I thought I would not have to give any other oath, but when I went to confession I told the priest that I had given a false oath in order to save the men and then he said to me, ‘In the honour of God do not give another false oath and damn your soul.’

Mr O’Brien QC – You hear, gentlemen, what she says about the priest.

Mr O’Sullivan – Don’t sir, it is very improper.

Wm Browne, a respectable looking man, was the first witness called for the defence. He deposed that on the morning of the day Browne was murdered he met the prisoners coming from their house and going in the direction of Scartaglin.

To his Lordship – It was about eleven o’clock in the morning and they had the same clothes on them as they have now – not black clothes. I also saw a dog with them.

Maurice Healy was next examined. He stated he lives about half way between the house in which Browne lived and the village of Scartaglin. The prisoners passed by his house that evening about half past four or five o’clock; the reason he knew it was about that hour was because a postman (who generally passes by his door about four o’clock) had passed his house shortly before; the clothes they then wore were not black, and they went across the field, not towards Browne’s house, but in an opposite direction; they had a dog with them at the time.

In cross-examination nothing material was elicited.

Daniel O’Brien examined by Mr Lawrence, stated that he was a national teacher at Kilsarkin; on the week Browne was murdered he kept his boys late at school preparing for the Result Examinations and it was four o’clock when the children went away the day of the murder. Redmond Connor and his brothers were in school that day.

Redmond Connor, examined by Mr O’Sullivan, stated he went to Kilsarkin to school and lived near Browne’s place. On the day of the murder he left school in the evening, and went home through the fields, and after crossing the river he met the prisoners; he did not notice the dog; and they were dressed as they were now; he knew James Barrett; he got out on the road at the Cross, and saw there Mrs Browne and Bridget Brosnan; he ran part of the way; and going down he saw Browne leaving the meadow, and saw two men coming down to him; they wore long cloaks, and were up quite close to him; the men fired two shots, and Browne ran; the men ran after him and fired two more shots, and Browne fell; the men then ran in the direction of Castleisland; he made no delay after seeing the prisoners until he got to Browne’s; I was examined at the inquest.

Cross-examined by Mr O’Brien QC – I met no person before I met Poff and Barrett; I saw Mr Davis next day and I did not tell him that I saw the two prisoners; I said nothing at the inquest about seeing two men; it was after the prisoners were arrested that I told Mr Davis I saw them.

Maurice Connor, examined by Mr Lawrence, stated that he was with his brother, the last witness from school, until they got to the river; witness had boots on and his brother had none so the brother crossed the stream, settled stepping stones for them, and then ran away; at that place Barrett and Poff passed them; he remained talking to them a little and then went on, until about six minutes afterwards he heard the shots fired; Poff and Barrett were gone in a southern direction.

To Mr O’Brien – I never said a word about meeting Poff and Barrett until they were arrested; I did not see a dog with them, but they might have one unknown to me; I was speaking to Barrett’s father afterwards about the matter.

His Lordship – When Mr Davis asked you about the matter that night, why did not you say that you saw Poff and Barrett and to ask them as they must have known something about it.

Witness – I never thought of those men at the time, as I know they could not have done it.

Bryan Connor, the third brother, gave corroborative evidence.

Cross-examined by Mr O’Brien – How do you know it was six minutes after you met the prisoners that you heard the shots? I walked it afterwards with a watch. Whose watch was it my boy? It was another man’s watch. What is the name of the other man? (no answer). Come sir, tell it! Tell it sir? (no answer). Whose watch was it sir? Jerry Nolan’s watch.

Is he a first cousin of Poff’s?

I don’t know, sir.

Is he a first cousin of Nolan’s?

I think he is sir.

His Lordship – Why didn’t you tell at once the name of the man who owned the watch? What reason do you give for not answering (no answer). Very well, go down.

Mr O’Brien – I would now ask your Lordship that there shall be no communication between these witnesses.

His Lordship – Very well.

Mr Horgan, solicitor for the defence – I was speaking, my lord, to Mr Nolan who is instructing me here, and whom I do not intend to produce, and I think I have a perfect right to do so.

Mr O’Brien – Jerry Nolan is a baker in Castleisland.

His Lordship – Who sent you to Jerry Nolan’s for his watch? No one. You went yourself for it? Yes, my Lord.

To Mr O’Sullivan – There were a number of police out firing shots and measuring this place, and that was the reason I went to Jerry Nolan for the watch; the prisoners are no relation of mine.

Hugh Brosnan deposed that at the time Browne was murdered, Poff had cattle grazing on his (witness’s) father’s land; on the day of the murder he saw the two prisoners going in a south-westerly direction; the prisoners were dressed as they were in the dock and had not black clothes on them; they came to the land for the purpose of looking after the cattle; they had a dog with them and went hunting rabbits.

To his Lordship – They came to the farm about five o’clock; Browne’s house is about half a mile from where they were hunting the rabbits.

Cross-examined by Mr O’Brien – I never saw them hunting rabbits there before, but they could be hunting there without I knowing it.

This closed the case for the defence and at the request of his Lordship.

Mrs Browne was recalled. She stated that the men she saw running away appeared to her to wear black clothes; she did not notice anything in particular about their appearance, they were going so fast she couldn’t take particular notice of them.

The Crown then went into rebutting evidence.

Mr H F Considine RM recalled, stated he heard the evidence of the last witness and said it would take about 21 minutes to go from where the last witness described the prisoners as being to the scene of the murder by going through the place where a whiskey bottle was found; in reference to the place where the two Connors said they saw the prisoners, he said it would take 13 minutes to go from that place to Brosnans, they could go from the same place to the scene of the murder in six minutes.

The little boy Horan, recalled, stated he saw the feet of the men who fired shots at Browne; there was one ditch between him and the men; which was low; he could see their knees; the black coats they had came down to their knees.

Sub-Inspector Davis recalled, stated in reply to his Lordship there were two ditches between the previous witness and Browne.

Mr Lawrence then addressed the jury on behalf of the prisoners. He said he felt confident there was no person more deeply impressed with the serious and painful duty they were engaged in than they were themselves, and without any preface he would address himself to the evidence of the case. He asked them to say that the innocence of the prisoners was most clearly established. The witnesses might be divided into two classes – one class who saw the men who committed the deed of blood; and there was another class who saw the prisoners at a distance from the spot and, fortunately, also saw the murderers escaping. He asked the jury, from the evidence of the Connors, to say if it were not clear that the prisoners were not and could not have been the persons who committed the crime. He (Mr Lawrence) found some difficulty in determining what theory the Crown presented to them. It at first appeared as if they wished to show that these men had followed Browne from Scartaglin, dogged him to his home, and there slaughtered him on his own land, but their recalling of Mr Considine seemed to be for the purpose of showing that the prisoners after meeting the Connors went round the base of the hill and so came back to the place where the man was murdered. Many curious things had occurred, and the feeling in the country was now so strong and vehement in putting down deeds of blood that it was incumbent on counsel for the prisoners to exculpate them by positive proof of their innocence. His learned friend, Mr Sullivan, and himself had cheerfully assumed that responsibility. They brought up a body of witnesses who went through the searching ordeal of a cross-examination and came out of it unscathed and unharmed. It appeared that Poff went to Scartaglin to get a letter for him which he had been told was lying in the Post Office and there was nothing unusual in doing that in a country district. Counsel said if there was a word of truth in the story of Redmond Connor the prisoners could not have committed the murder for he met them going innocently on their way in a southerly direction before the murder was perpetrated. Other witnesses saw the dog with Poff and Barrett but the Connors did not say anything about the dog and possibly it was in one of the rabbit burrows at the time. The fact of the Connors not seeing the dog showed the strength of their testimony and that their story was not got up to fit in with that of the others. That was a circumstance, counsel contended, that ought convince the jury that the boys were telling a truthful story. Then, as to the clothes. It was proved that the prisoners were not dressed in dark clothes or in long coats; but the boy Horan said the men who committed the murder wore long black coats down to their knees and Redmond Connor, who said the same of the man he saw escaping from the scene of the murder. It was not for him to say what the motives were which induced the old woman Bridget Brosnan to swear as she had done – whether it was rancour against the prisoner or due to the infirmity of her extreme old age – but one thing was clear, that it was not true. She heard shots and must have known that a tragedy was enacted and yet in speaking to Mrs Browne she did not mention one word about it but said, “I suppose so,” when Mrs Browne remarked that she thought fowlers were about; and later on when she met the daughter of Mrs Browne on the road crying, and the child said her dada was murdered, the woman said nothing of what she now deposed to. At the coroner’s inquest Mrs Brosnan said she did not know the men; and were the jury now to believe her after she had admitted taking a false oath already? Counsel then referred to the three entries in the notebook of Sub-constable Dallas, with reference to statement made by Poff to Barrett, in the hearing of several policemen, when the charge of murder was hanging over them and the rope was dangling in their sight – which testimony he characterised as unreliable – and said that the entry now brought to bolster up a case which had failed in every other way. In conclusion, he would leave the case in the hands of the jury, confident that they could not on the evidence bring a verdict, the inevitable results of which would be the ignominious death of these unhappy men.

Mr O’Brien, replying on behalf of the Crown, said a dreadful murder had been committed in this blood-stained district of Castleisland – a district over which the assassins had often stalked with impunity – the most blood-stained district in the annals of our country. He submitted that the evidence produced by the Crown conclusively pointed the guilt of the prisoners, and with all the responsibility of his position upon him he appealed to them to act upon the evidence and not to let the prisoners to go back to Castleisland to riot in human blood. There was one man in the court whom the prisoners’ counsel could have called upon but who was not produced – Father Scollard. The prisoners might have produced him to show that Mrs Brosnan was not at confession. He could have stated that, though he could not have communicated the secrets of the confessional, and if it was shown that she was not at confession then there was an end to the case. When she was asked with whom she had been at confession, they would remember the graphic way in which she recognised the priest, and calling him ma crusha. She said it was in consequence of the confession that she gave her evidence under the sanction of her oath and under the sanction of the priest who had a divine mission to fulfil. With reference to Dunleavy they know that the moment he was discharged from custody he bolted. He asked them would they rely upon the evidence of the boys named Connor as against the distinct swearing of the woman, Mrs Brosnan, for if they believed her there was an end to their evidence. Did they ever see a little boy more dumb-stricken than Bryan Connor when asked about the watch, which he said he got from Jeremiah Nolan, to whom he went for it of his own accord, and though Nolan was in court he was not produced? If the old woman, Mrs Brosnan, invented her story she must be a greater assassin than the murderers of Browne. She was an old woman, fast advancing to her grave – the grave was near at hand and eternity was within view. The prisoner’s counsel had her whole life to ransack but did they by a single question impeach her life with dishonest conduct in one single particular? It was as plain as light that the priest to whom she went to confession told her to tell the truth, she having denied any knowledge of the murder in the first instance, and if the jury did not see that, let them abdicate their pretensions for intelligence. The prisoner’s counsel suggested no motive whatever why her evidence should not be believed. They were asked not to believe her after being with her priest, and they knew how Catholic people revere the confessional and they saw that how, with a touch of pathos, he would ever remember – how the penitent recognised her priest and for his (counsel’s) sake, and for the sake of the Irish people, he hoped that the country people – the peasants of this country – would ever seem to regard their priests with the affection and reverence which that old woman regarded the priest who sat there that day. It was only when she was at confession that her reluctance to give evidence against the prisoners disappeared; it was she was coerced to tell the truth. He argued it was plain the murderers were not disguised on the day in question for if they were, would Browne have walked, as described by some of the witnesses, towards them when they called him. Was it not likely that those prisoners coming from the district of Castleisland – a district, if he might use the expression – reeking with human blood, would know something about making their defence and their alibi. Something had been said about a motive; what had they proved in that court a few days since. A party of men enter a house, shoot the owner in the legs, warn him for life, and no motive. In one of the most remarkable trials that ever took place in that country – he believed it was the most remarkable – he referred to the Maamtrasna murders – though the men were convicted, there was no evidence of a particle of motive. The prisoners counsel under the Winter Assizes order, could produce a priest or any man of respectability, to give a character to the prisoners, but they did not attempt it. If they were to look for motives in this unhappy country nowadays as many and many a criminal would escape with impunity and their courts of original jurisprudence would become a farce.

They had been asked to discredit the testimony of Sub-Constable Dallas – to recklessly believe that he was perjuring himself to murder two men. If he was doing so was he not a fiend in human form? The words he overheard were the most likely that could have been used and to reject this evidence they should believe he was a fiend in human form as against men about whose character not a word had been said. If they did believe him counsel asserted it spoke with the force of a trumpet the truth of the aged woman’s story. Mr O’Brien concluded – if you believe that, then I appeal to you to do your duty. Spare them not if you believe that they dipped their hands in human blood. You are there to vindicate the law and to protect human life. It is your duty to act like men, courageously and with that fearlessness which becomes your privileged position and shrink not to endeavour to free from slaughter this blood-stained district. I submit to you that the evidence leaves no doubt. I appeal to the love which you have for the sanctity of human life and the love you bear our common country; I appeal to the God who looks down upon you and me to give you strength to do justice in this case (applause).

The court then adjourned until half-past ten this (Friday) morning when his Lordship will charge the jury.

The jury were accommodated in the Imperial Hotel for the night in charge of policemen.[9]

Day 2: Friday 15 December 1882

Before Mr Justice Barry resumed the hearing of the Castleisland murder case in which prisoners Sylvester Poff and James Barrett stood charged with the murder of Thomas Browne at Dromultin, near Castleisland on the 3rd of October last.

The Crown was represented by Messrs De Moleyns QC and P O’Brien QC (instructed by Mr Alexander Morphy, Crown Solicitor).

Messrs D B Sullivan and G Lawrence (instructed by Mr Maurice J Horgan, solicitor, Tralee) defended the prisoners.

Mr O’Brien said that Sub-Inspector Holmes, Tralee, was now in attendance and could be examined if his Lordship permitted.

Mr Sullivan objected to any further evidence being received.

His Lordship decided not to hear the evidence and proceeded to charge the jury. He said – Gentlemen of the jury, under any circumstances would I think it necessary addressing such a jury as I see empanelled in that box, to occupy time in begging your most grave and serious attention and consideration to the momentous issue which it is now my duty to submit to you for your final determination; but if any such idea could have entered my mind, it would have been entirely removed by the becoming alacrity with which you acquiesced in the suggestion that the hearing of the case should be discontinued on yesterday evening and adjourn the conclusion of it over until this morning, and thus you cheerfully acquiesced in an arrangement calculated to impose great personal inconvenience upon you, and I saw that that was the result of your deep sense and appreciation of the gravity of the duty that devolved upon you. You were determined that you would not be hurried or allow yourselves to be hurried or hastened to any inconsiderate conclusion. Neither shall I occupy your time in making any observations upon the enormity of the crime, the startling features of the crime, into the circumstances of which you are empanelled to investigate – to inquire. To state that in the broad noon day, within sight of his own dwelling-house, under the very eyes, you may say of himself and children, a man engaged in the peaceful avocations of agricultural life should be shot down by a pair of assassins in a matter so startling, so appalling, that if we read of its happening in some distant country where the blessings of civilisation have never reached, where there is no law, no order, where the civilising influences of Christianity have not penetrated – if we read of its happening in such a country as I have described, we would regard the narrative with astonishment, perhaps with credulity, but that it should happen in this Christian country in the year 1882, is a matter that must strike with alarm the mind of every well-regulated man. That Thomas Browne was audaciously and foully murdered on the 3rd of October, about the hour of 4 o’clock – it might be half an hour sooner or later – that he was shot dead on his own land almost within sight of his wife and children there can be no doubt at all and in the very able defence conducted by my friends, Mr Sullivan and Mr Lawrence for the prisoners, it was not suggested that the crime was not committed by two men who went in off the road into the field. The defence had been narrowed, and I would venture to say wisely narrowed, to one question, namely, whether the two men who committed the murder were the prisoners at the bar or not. It is a case remarkable in some respects as regards the details of the evidence. It is a case in which the defence is what was known as an alibi and though that word carries with it something of an unpleasant meaning I do not use it in any such sense. That is the correct, legal, technical name of a defence which seeks to establish that the prisoners at the bar were elsewhere at the time of the commission of the murder. But the peculiarity of the alibi in this case is that the alibi itself brings the prisoners at the bar on the spot within a few minutes of the time at which the murder was committed. In that it is a most peculiar case and as Mr Lawrence in his always logical and well-reasoned address pointed out, it was a case that did not depend for the defence of the prisoners upon more periods of time – he put it in apt language when he said it relied upon the sequence of events. Gentlemen of the jury, I will call your attention to the leading features in the evidence but I shall before doing so simply premise that the decision of the question of fact, guilt or not, is entirely for you. If gentlemen, in the observations I make I seem to point at any one moment to any particular conclusion, understand perfectly from me now that I don’t intend by anything that I say to in any way control or dictate to your judgment on the question of fact. It is your duty to decide the fact; it is your privilege to decide the fact; it is the right of the prisoner to have the fact decided by the jury, and it is the right of what is called the Crown – the prosecution – to have the fact decided by them. It is not my province, my duty or my privilege. The question of fact is entirely for you and to your judgment, conscience and determination do I commit it. His Lordship then proceeded to review the evidence. He said that upon the testimony of one witness, Bridget Brosnan, the Crown case would stand or fall, for if her evidence was wiped out of the case he would deem it his duty to tell them there was no case for their consideration at all. He need scarcely tell gentlemen of their experience and intelligence that there was no better guide in connection with the testimony of a witness more deserving of their consideration than the demeanour of a witness in the witness-box and it would be for them to say how far they regarded the evidence of Bridget Brosnan in a manner calculated to challenge their credence. It was difficult to believe she was mistaken. If she was not mistaken, she was either telling the truth or she was wilfully telling what she knew to be false. Before they believed the latter, that a woman, such as had been described by Mr O’Brien in his powerful reply for the prosecution – they should come to the conclusion that a witness coming into court under such peculiar circumstances would conceive a project so diabolical as that; she would with wilful falsehood swear that the two men who entered the field were the prisoners at the bar whom she knew well. His Lordship, having referred to the evidence of Mrs Browne, addressed himself to the testimony bearing on the dress, which the assassins wore on the day of the murder. He said the evidence of the little boy, examined for the prisoners, was assailed by the Crown who suggested that he had been induced to make a statement which would tally with the evidence of other witnesses, but that was a matter for the consideration of the jury. With reference to the evidence of Sub-Constable Dallas, prisoner’s counsel asked if the extraordinary conversation he had overheard was ever made. Why was it not heard by other policemen who were close at hand. Now the jury know that a whisper or an expression in a low tone of voice might be heard by one person out of eight. They would have to consider whatever the words were used, and also what inference they would draw from them. It was plain it was not an afterthought of the Sub-Constable, and it should also be observed that the conversation was used from first to last as evidence against Dunleavy and not against the prisoners. His Lordship did not think there was any evidence, from which they were to assume that the witness was telling what was untrue. Of course it was possible that he had mistook the words or perhaps that he invented them himself. If they believed the words were used they should ask themselves what was their meaning. It did appear strange that Poff would run the risk of such an expression where he might possibly be overheard, but however, their experience told them that frequently men charged with grave crimes conducted themselves in a manner extremely indiscreet and unaccountable. The question was did he use the words and if so were they indicative of a consciousness of guilt.

[The prisoner Poff here stood up in the dock and said something which was unintelligible]

His Lordship (To Mr D B Sullivan) – Do you wish that the prisoner should be allowed to speak. I will never allow any man’s mouth to be shut who is on his trial for his life.

Mr Sullivan made no answer.

Poff – It was I got Dunleavy arrested.

Mr Sullivan – I would advise him to hold his tongue, my Lord.

Poff – I need not be in dread of him. I know he must have information wherein –

His Lordship – Possibly the best thing you could do would be to take the advice of your counsel.

Mr Sullivan – I think so, my Lord.

His Lordship (continuing his charge) said – If Dallas invented his evidence his guilt would be as great as that of the other assassins who shot Browne. That he would now exhume this fabrication, spent in its own purpose with a view to taking away the lives of the prisoners, was a terrible suggestion to make. Such things had occurred before and it was for the jury to say whether it had occurred in this case. The first question they would have to ask themselves was did the evidence for the Crown, not encountered by any other testimony satisfy them of the prisoners’ guilt. Referring to the evidence of the witnesses (Connors), his Lordship said if their evidence was truthful it was impossible that the prisoners at the bar could have been the assassins. He also referred to the circumstances in the evidence of the boy Connor, respecting the watch, to his hesitation in answering where he had got it, and to the improbability of his story altogether. They all knew from their experience in courts of justice – not less in recent times than in former times – that there is a facility in getting persons to come forward to swear in favour of a friend who was in trouble and as he had often repeated the result of their experience was men, boys, women or girls would be found to come forward – he would not go further than to say to strain a point – in favour of an accused friend who would rather die on the scaffold than say a word against their bitterest enemy. It was not because a witness was produced in favour of a friend to establish an alibi that therefore he was to be laughed at, scouted out of court, or disbelieved. Having drawn attention to the evidence of other witnesses, his Lordship said they would perceive all the testimony largely came round to what he originally laid down, that the case should stand or fall on the evidence of Bridget Brosnan. Of course, any evidence tending to corroborate her testimony should be taken into account. In his opinion the evidence of Dallas, in the absence of Bridget Brosnan’s, would not warrant the jury in convicting the prisoners. They should take the evidence as a whole – they should consider how one piece of evidence bore upon another. It was not disputed on the part of the prisoners that the two men Mrs Brosnan saw entering the field committed the murder. The question was were they the prisoners, and before they came to that conclusion they should give the amplest attention and consideration to the evidence for the defence. They had the contradictory testimony respecting the colour of the clothes the assassins wore, and which they would also consider. If on the whole of the case they had a doubt – such a doubt as they would have in their ordinary transactions of life – an independent doubt – not one arising from fancy or cowardice or misunderstanding or for the purpose of ventilating some intelligence superior to others – that was not the doubt that should operate in their minds. They were called upon to perform no other duty than one which they had been performing every hour of their life. If they had a doubt on their minds of the character described, no matter what their abhorrence of the crime might be, the prisoners should get the benefit of it; but if they were convinced in their hearts, in their intelligence, judgement and conscience that it was the prisoners who committed that deed, they should find them guilty regardless of the consequences and he could only say may God direct them to a right conclusion.

Before the jury retired the prisoner Barrett was made to turn round in order that they might see his back.

After an absence of an hour they returned into court, and the foreman handed the issue paper to the Lordship.

His Lordship – They wish to have Maurice Horan, the little boy, asked if he saw Redmond Connor either in the field or on the road, and where he was coming from. He already said he was coming from school at Scartaglin.

The witness referred to was then examined and said he was coming from school but did not see Redmond Connor at all in the field.

His Lordship (to the jury) – Does that satisfy you?

A Juror – Yes.

Mr Sullivan was about saying something when Mr O’Brien objected and His Lordship said every question to be asked should be asked through him.

Redmond Connor was then recalled and stated he knows Maurice Horan and saw him in the field where the murder took place shortly after; he was going out on the road at the time.

The jury again retired, and in half an hour the foreman returned, and made a communication to his Lordship and again withdrew.

His Lordship (to counsel) – The foreman has informed me there is no chance of the jury agreeing. Do you wish that they should be called out and that I should put to them the usual question. From what has occurred, I don’t see any use in it. What do you say, gentlemen?

Mr O’Brien QC – We leave it to your Lordship’s hands.

Mr Sullivan – I say the same, my Lord.

The jury were then called out.

His Lordship – Well, Mr Foreman, you have told me that you don’t think there is any chance of the jury agreeing.

Foreman – Not the slightest.

His Lordship – Can I be of any assistance to you in any way – reading over any part of the evidence, or answering any question within my province?

A Juror (Mr Leader) – None, my Lord.

His Lordship – Then in that case, I discharge you, gentlemen.

The jury were then discharged.

Mr Sullivan asked what course the Crown intended to pursue with reference to the prisoners.

Mr De Moleyns said they would answer the question in the course of the following day.[10]

Day 3: Saturday 16 December 1882

Munster Winter Assizes. The Castleisland Murder Case. Mr De Moleyns QC said he might mention for the information of the prisoner’s counsel in the case of the prisoners Sylvester Poff and James Barrett, charged with the murder of Thomas Browne at Dromultin near Castleisland on the 3rd of October last, that they would put the prisoners on their trial at the present assizes. He (Mr De Moleyns) would mention later on to counsel the time at which the case would be taken up.[11]

Second Trial

Munster Winter Assizes

Day 1, Wednesday 20 December 1882

His Lordship, Mr Justice Barry, sat in the City Court at half-past ten o’clock yesterday morning and resumed the business of these assizes.

Two men named Sylvester Poff and James Barrett were put forward again, the jury having disagreed in their case last week, charged with having, on the 3rd October last, wilfully, feloniously, and with malice aforethought, murdered one Thomas Browne near Castleisland in the county Kerry.

Mr James Murphy QC attended specially from Dublin to conduct the prosecution on behalf of the Crown.

He was assisted by Messrs De Moleyns and O’Brien QCs, instructed by Mr Alexander Morphy, Crown Solicitor, Kerry.

The prisoners were defended by Messrs D B Sullivan and G Lawrence, instructed by Mr M Horgan, solicitor, Tralee.

The special jury panel having been called over the following gentlemen were sworn on the jury: Isaac Banks, foreman; William Ross, William Varian, Thomas Lambkin, Francis McCarthy, Samuel Anglin, Henry Good, Francis Sergeant, Christopher Croffis (?), Maurice Hickey, Richard Perrott, Henry Smith.

The following were challenged – Richard Edward Longfield, James Penrose Fitzgerald, Lace (?) Julian, James Johnson, William Banister, Thos Thompson, John London, William Henry Cade, Michael Russell, Peter Allen, Henry L Young, Captain Anthony Morgan, Robert Julian, Thos E Holland, William Moore Hodder, Richard Mason Croffis (?), Francis Herd, William Welland, John Sherlock, John Reid Kilner, B Creagh.

The following were ordered to stand by: Myles Regan, John McCarthy BL, Grand Parade; Peter O’Neill, James Wise, Michael Daly, Richard Lombard, Thomas Ryall, Abraham Adams Hargrave, Patrick Moore, James Lane, Jeremiah Carey, Thomas Walsh, Robert Rice, Daniel Arnold, Patrick Walsh, David Saunders, Michael Buckley, Joseph W Hitchey, Daniel Flynn, Wm J Kelly, John Richardson, Ruben Harvey Jackson, Wm Ahern, Patrick Daniel Hogan, John Byrne, Patrick Cronin, John Banks, Simon Bowen, John O’Brien, Edmund Connors.

Mr Murphy, in opening the case for the prosecution, said the jury had heard the charge that had been preferred against the prisoners at the bar. It was that of wilful murder, or what he might call the assassination of a man named Browne in a place in the county Kerry near Castleisland third day of October last.

He was sure it was unnecessary for him to tell gentlemen of their intelligence that the highest order of intelligence is as necessary in the consideration of this kind on their part as it was necessary on the part of the distinguished judge who presides here to aid and direct the jury so far as he could by his legal experience and skill. They (the jury) had been selected under special circumstances as special jurors for the trial of criminal cases in this country at present. There should be a selection used on such an occasion in order to get men qualified to sit as special jurors and also for those who are qualified by their position in life to discharge that duty; and further, selection had been made so far as those who conduct the prosecutions on behalf of the public are enabled to do so to have men of intelligence, firmness and independence and men who, they trusted, would discharge their duty with conscientiousness and intrepidity. But, as he had said just now, it was he was sure unnecessary for him to say that it required eminently careful consideration on their part as well as the evidence that will be offered on behalf of the prosecution as any that can and may be offered on behalf of the prisoners and that they would bestow on the case that would be made for them or would be urged on their behalf and he was sure that everything would be urged that ability and ingenuity could suggest by his learned friends, who he was glad to see conducting their defence in the case.

They would give due weight and consideration to all that would be urged on the prisoners’ behalf as well as on behalf of those who would conduct the prosecution and if, after having heard the evidence in the case, and applying the best judgment and consideration that they were endowed with to it, they arrived at a satisfactory conclusion with respect to the guilt of the prisoners, they were bound to declare that conclusion on their verdict and if they entertained a reasonable, manly and honest doubt on the question, they were called upon to bring in a verdict of not guilty in favour of the prisoners. He now wished, first, to state to them some facts that would be established to their satisfaction beyond doubt with respect to the circumstances under which this murder took place. This unfortunate man, Thomas Browne, had been with two other tenants named Fitzgerald, tenant to a gentleman to whom he believed they had each to pay a rent of about £40 a year. The land was subject to some head rent, and Browne some time since became purchaser from this gentleman who was the immediate landlord of him and the others, for some £1,500 and so he became the landlord of his ex-tenants. Now save that he had put himself in that position, and that having got into that position, it might be supposed that he had acquired some unwarrantable status in the country, they (the Crown) knew of no other reason to account for Browne’s assassination. He was, he believed, a man who was on kindly terms with his neighbours, ready to do acts of kindness towards those who were poor about him. But there is no doubt that the order went out for the assassination of Browne, and that it sprang from some secret organisation or confederacy, which had he regretted to say, exhibited their power and their dispositions too often before with impunity in assassinations committed in the broad noon day in that same district and rendered the place as it had been called by one of his learned friends, and very properly designated, a blood stained district, that seemed to be almost accursed from Heaven from the way that the demon of assassination ranged there with impunity. When a terrible degradation of that kind or demoralisation arose in a district when humanity itself seemed to be effaced and a vast proportion of the inhabitations – God forbid that they did suppose for a moment that in a large district the whole population were ready at once to be aiders and abettors in fearful crimes of this kind, and that they became so suddenly lost to a sense of religion, morality and humanity itself, or to take part in those deeds – are placed by a few bad men, a mere handful of assassins, in a state of terror and alarm that utterly deprived the public and those connected with the public peace and order of the country from any chance of obtaining information that might lead to the successful prosecution or pursuit of those criminals, and they would be satisfied in this case that the assassination of poor Browne, which took place between 4 and 5 o’clock, near to 4 perhaps, in clear daylight, in the afternoon of the 3rd October, was perpetrated by some persons who considered that they had a position in the district and that they had it so completely under their control and terror that no matter who might have been the spectators of the deed they would not on the peril of their own lives dare so utter a word against them. It would be idle to suppose that strangers could come from a distance from circumstances they would [page torn illeg]

… home before two o’clock and then went out a little distance from the house himself in order to collect some hay in the meadow that had been scattered about by a storm that had taken place a day or two before that. There resided tolerably close to his house a very poor and aged woman. She lived by herself. She was one of the old women in the country going about occasionally from house to house. She knew well and was known to everyone in the neighbourhood. He believed that they would find that she was blameless in life, she was very aged, about seventy years. She had frequently been indebted to Mrs Browne for little acts of kindness, and there was no doubt that this woman Brosnan apprehended that day from what she had seen, as he should describe to them immediately, some danger to Browne. She felt that murder was in the air! In the early part of the day, and this would be beyond all doubt, she had seen going into Scartaglin together three persons – the two prisoners, Sylvester Poff, who was comparatively a stranger in the place, his cousin the other prisoner Barrett, and a man named Dunleavy. So far as they could see they had no regular business that day in Scartaglin. They had no, he was going to say, joint occupation or pursuit unless the plan to assassinate Thomas Browne, which he thought they would be satisfied was their joint occupation and pursuit on that day. They had no other so far as they could ascertain, legitimate business there. In the town of Castleisland on the same day there were two men named Fitzgerald. Their names would necessarily be drawn into the case. They were the other two tenants that had been joint tenants with Browne. When he became landlord it was well known that an unfriendly feeling existed between Browne and them. Dunleavy, Poff and Barrett remained in Scartaglin during the day knocking about. Poff and Barrett left Scartaglin together and beyond all question they were at the place where the murder took place and substantially at the time that it occurred. When the three men were going in the morning into Scartaglin, old Mrs Brosnan had seen them and they knew her. She conversed with them before they entered the village. It so happened – and he thought one might certainly be allowed to use the term that it providentially happened – that just before the time of poor Browne’s assassination, some little business – he believed cutting rushes – brought the poor creature from her house. She had been engaged in a fence trying to get a bundle of rushes on her back when she observed two persons whom she knew coming along the road and crossing a fence into one of Browne’s fields. She knew poor Browne was in the meadow and, apprehensive of danger to Browne, she rushed to his wife and her house. Mrs Browne would describe to them the appearance of the old woman Brosnan. She was pale and terrified and while yet they were speaking, shots were heard fired from the meadow or from the field where poor Browne was. Those were the shots that had caused instantaneous death to poor Browne. He lay a murdered man on his own field while the woman Brosnan was yet speaking to his wife. The old woman knew then her mission was in vain. When she had run to the house she had some hope that help was at hand but it was soon put an end to and what followed was the wail and cry of the children when they found their father lay a murdered man in the field. An inquest was held. This old woman was before the coroner, paralysed of course with terror. She concealed what she knew. She afterwards sought her priest and after that she made known what she knew about the men she had seen crossing the fence and who were undoubtedly the persons who perpetrated the foul crime that had been committed on that day. They knew that in any district which had become overspread – as this unhappy region had been – with crime, a place where there had been as much peace and security until recent times, as could be found in any other country perhaps in Europe.