It was at the Cork assizes my enemies all swore

That I shot James Donovan and laid him in his gore.

The Jury found me guilty, the judge to me did say:

On the ninth of February, ninety-five, will be your dying day.

From the song, ‘The Trial of John Twiss’1

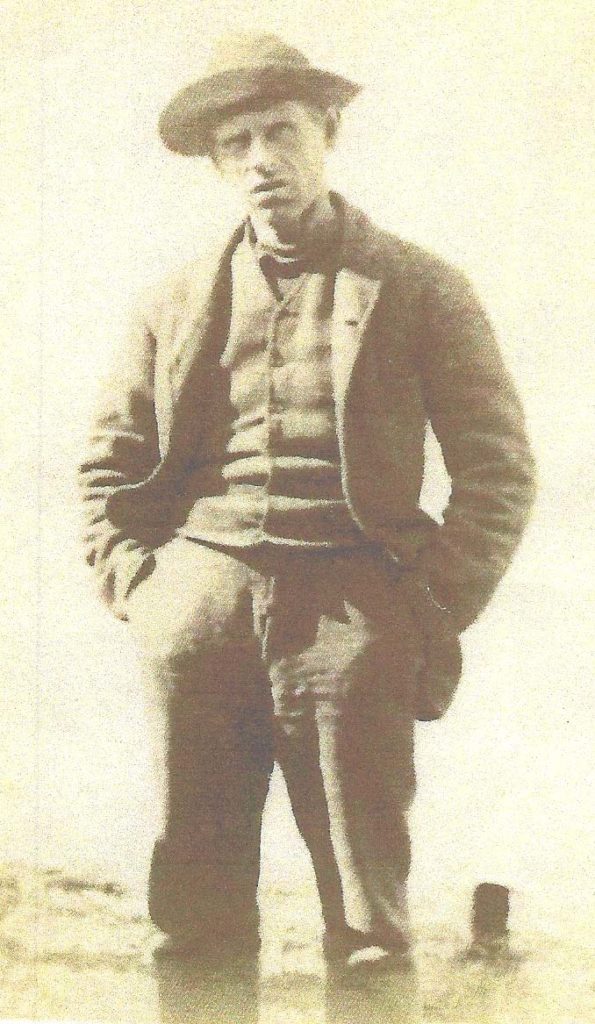

The voice of John Twiss, whose trial, conviction and sentence are documented in the O’Donohoe archive, continues to call from the grave more than 120 years since he lost his life at the gallows.

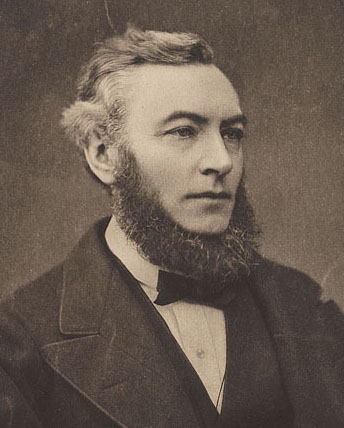

Almost 70 years ago, Twiss’s junior counsel, Alexander Martin Sullivan, who went on to a successful legal career and represented Roger Casement in 1916, published a memoir.2 He was then a man of 81 years, reflecting on his life and career as one might do in those mellow years.

He reflected on his youth and his first murder case, when only a year of two at the Bar, which was the case of John Twiss. He wrote, ‘To this day I have not forgotten the strain and the mystery of the case.’

Just a few years earlier, before he put pen to paper for his memoir, he had received a bundle of papers which on opening, were found to be the printed depositions of the magisterial enquiry in ‘that first and most terrible criminal case’. Sullivan put the papers away, unable to ‘stir up again the most unpleasant memories associated with that trial.’

However, during a tidy up, he unearthed them again and ‘there came back to me with a shock, the scene in the Cork Corn Market building in which the Winter Assizes were held in 1894.’

He wrote,

I, a youngster at the Bar, interrupted the cross-examination by my leader of the most important crown witness, told the witness not to answer his question and implored my leader to withdraw it … My leader repeated the question and I repeated my objection, and the Lord Chief Baron on the Bench, who knew that I was right, observed that a junior counsel could not overrule his leader, and if the question was persisted in it must be answered.

Sullivan went on to describe how the question was persisted in and answered, which rendered admissible two documents which ‘made certain the conviction of John Twiss, our client, who was subsequently hanged’. As a result, concluded Sullivan, Twiss was convicted of a crime for which he was never tried.

Sullivan gave a full – perhaps cathartic – chapter to the trial.3 He described how the representative of the Crown had ‘skilfully introduced into the testimony of wavering witnesses many facts of the most prejudicial character that were not relevant to the case. This had been done designedly’.

Sullivan relived the delivery of his closing speech for the defence to the jury, when he had ‘the dreadful consciousness of the futility of my advocacy … I knew that the case was lost, and when the verdict was returned I almost lost consciousness.’

Sullivan described the embarrassment of the Chief Baron, who having been compelled to admit irrelevant and incriminating documentation, had then to ‘remove their effect from the mind of the jury, an utterly impossible task.’

‘Time has to some extent appeased the oft-recurring horror of that early experience,’ he went on, ‘and I wish that I could say that the terrible events that culminated in the execution of Twiss fifty years ago had become ancient history.’4

At this distance, it is to be lamented that A M Sullivan did not hold the reins for the defence on that fateful day.5

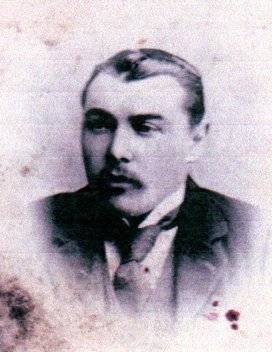

His leader in the courtroom blunder was Robert Arthur Powell, who died a few years after the trial aged 36.6 Powell had been called to the Bar in 1886. With limited experience, teamed with a junior counsel on his first murder case, it makes clearer the weakness of Twiss’s legal representation up against the might of the Crown.

Sullivan and Powell had been instructed by Twiss’s solicitor, Patrick Riordan Fitzgibbon. He too suffered the tragedy of an early death but to this day, his descendants advocate the innocence of John Twiss.7

The Michael O’Donohoe Memorial Heritage Project has applied for the Presidential Pardon of John Twiss on behalf of his descendants. It remains to be seen if the ghost of John Twiss may yet be laid to rest.

My last hour is approaching, I hear the death-bell toll

The hangman he has pinioned me – I must now give up my soul.

You know that I am innocent, is all I have to say,

May the Lord forgive my enemies all on their judgment day.

________________________________

1 Songs of Cork (1978) by Tomás Ó Canainn, pp44-45. A copy of this book (which includes notation) is held in the O’Donohoe Collection, IE MOD/C47. Song titles: Amhráinín Siodraimin, Armoured Cat, Ballad of Charlie Hurley, Banks of Sullane, Banks of the Lee, Barr’s Anthem, Bells of Shandon, Blacksmith of Cloghroe, Blackwater Side, Boys of Fairhill, Boys of Kilmichael, Coal Quay Market, Cork National Hunt, Dear Cork City by the Lee, Down Erin’s Lovely Lee, Exile’s Return, Fifty Years Ago, Fylemore, Garnish, Gleanntán Araglain Aoibhinn, Groves of Glanmire, Johnny Jump Up, Kilnamartyra Exile, Liam O Connell's Hat, Lloyd George, My Home in Fermoy, My Home in Sweet Glenlea, Plains of Drishane, Pup from Claodach, Rally-Roh, Rookery, Salonika, Shores of Coolough Bay, Sorrowful Lamentation, Sticking Out a Mile from Blarney, Strands of Ballylickey, Sweet Kingwilliamstown, Tailor Bán, Toast to Beara, Tons of Bright Gold, Tórramh an Bhairille, Trial of John Twiss, Two TDs, Up in Gurrane, When Clon Came Home. 2 The Last Sergeant: The Memoirs of Serjeant A M Sullivan (1952); Foreword by the Earl of Jowitt of Stevenage. 3 The Last Sergeant, ‘Glenlara’, pp73-95. 4 Ancient history it is not, and the pursuit of justice for Twiss continues to this day. The Michael O’Donohoe Memorial Heritage Project awaits outcome of its application for the Presidential Pardon of John Twiss. 5 Further reference to Alexander Martin Sullivan (1871-1959) in the Dictionary of Irish Biography. 6 Robert Arthur Powell was born in Macroom c1861, the only son of Arthur Powell (d 19 October 1885). He entered King’s Inn in 1883 and was raised to the Bar in 1886. He was Revising Barrister. He suffered a stroke and died at Vickery’s Hotel, Bantry on 3 July 1897 leaving a widow and two children. A fund was got up for his family in the wake of his death. He was buried in St Joseph’s Cemetery, Cork on 5 July 1897. 7 John Roche, O’Donohoe Project Chairman, in conversation and correspondence with Maurice Buckley, Cork, grand-nephew of Patrick Riordan Fitzgibbon. Patrick Riordan Fitzgibbon was born in Newmarket, Co Cork on 16 March 1870, son of David Fitzgibbon, shopkeeper, and Mary (née Riordan). He qualified as a solicitor in 1892 and practiced from two offices in Newmarket and Dublin. He later moved to Bank Place, Mallow. He died at Bank Place, Mallow, Co Cork on 27 March 1899. He had been ill for a short time, his death caused by pneumonia, gastritis and syncope. He was buried in the cemetery of Clonfert, Newmarket. He left a widow, Elizabeth, daughter of John Leader and Susan née Williams. There was one child of the marriage, Patrick David, born 17 May 1898. P R Fitzgibbon had four siblings, Maurice, ordained in 1898; John, who continued the family business; Margaret who became Mrs Breen and Ellen, Mrs Quinlan. Reference, courtesy Maurice Buckley, from ‘A Link with the Twiss Trial’ by Bartholomew Egan, OFM, held in the Twiss papers of the O’Donohoe archive.