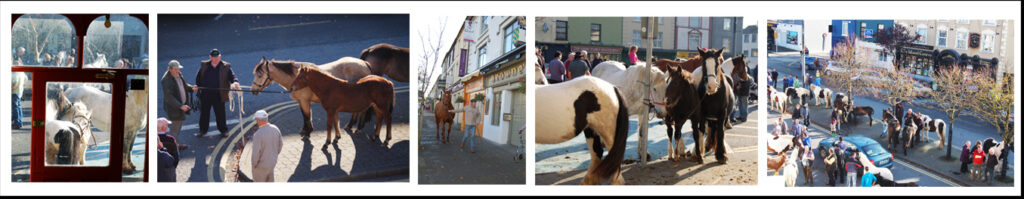

There can be little doubt that Castleisland’s historic First of November Horse Fair would have attracted horseman James Reynolds, whose early years were devoted to a round of hunting, race meetings and horse fairs.[1]

This much is learned from his writing, a career that commenced later in his life (in his 50s) and which revealed a man very widely travelled. His subject matter was broad – horses, ghosts, European travel, Palladian architecture – each book a treasure-trove of history and art combined.

Ireland, the land of his fathers (perhaps), had a particular value, and he left five books devoted to the country, Ghosts in Irish Houses (1947), The Grand Wide Way A Novel (1951), Maeve the Huntress, A Novel (1952), James Reynolds’ Ireland (1953) and More Ghosts in Irish Houses (1956).

When James Reynolds died in 1957, there was some confusion about his background. His birth place was given as New York, Virginia, and Ireland, creating not a little difficulty in attempting a biographical sketch. His death occurred in Bellagio, Italy, where in 1954 he had obtained an Italian passport.[2]

An obituary in the New York Times described him as of Irish descent, American by birth:

James Reynolds, author and artist, died on Sunday at Bellagio, Italy, according to word received here yesterday by his publishers, Farrar, Straus & Cudahy Inc. His age was 65. Mr Reynolds had a studio at 154 East Fifty-Fourth Street which he considered as home but he was seldom there. He spent most of his time travelling about the world. Last spring he suffered severe injuries in an automobile accident from which he had never completely recovered. He was best known for his flair for the whimsical, the supernatural and the romantic. Born in Warrenton, Virginia, of Irish descent, he had inherited the Irish love of the strange and inexplicable. His book Ghosts in Irish Houses was published here – with an introduction by Padraic Colum. It was followed by More Ghosts in Irish Houses and eventually, by Ghosts in American Houses.[3]

The notice described how Reynolds had been an artist of considerable accomplishment before he became a writer, and that all of his books were illustrated by himself:

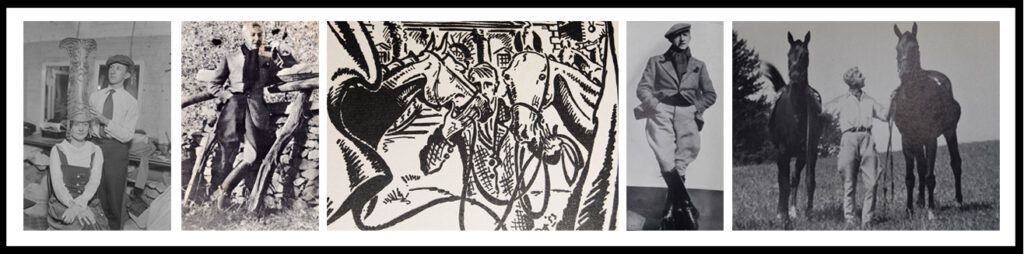

He had also written considerably on horses, was known as a painter of them, and at one time has bred race horses himself.[4] Among the murals executed by Mr Reynolds are those at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington. He also did the stage settings for a number of theatrical productions and did textile designing. He had lectured widely in this country and abroad.[5]

It is supposed his career began as a Broadway costume and set designer in the 1920s:

He was especially sought after for musicals, operettas and revues, including the 1921-1923 editions of Ziegfeld Follies, Dearest Enemy (1925) and The Vagabond King (1925). He was also involved in a number of non-musical works, including These Charming People (1925), The Royal Family (1927) and Coming of Age (1934).[6]

In a recent publication about early American theatre, Reynolds was described as a ‘red-haired Irishman from Warrenton, Virginia, the only contemporary whose flair and talent Robert Edmond Jones ever feared’:

Always popular because of his boyish charm and wit, he created elaborate decors and costumes for John Murray Anderson’s Greenwich Village Follies as well as Flo Ziegfeld’s Follies. His disarming talent added a panache to revues and musicals during the twenties that even Erte did not achieve … An interest in his Irish heritage generated several books by him on Ireland.[7]

The following anecdote relates to 1930, from which it is clear that the designation of architect may be added to his accomplishments:

I designed a country house for a Norwegian friend who lived near Stavanger. The house was built without so much as a door-handle in my original plan being changed. I painted two rooms, a music room and a large entrance hall. For design I fused a Palladian villa at Caldogno, near Padova, with the style of a big simple Norwegian manor-house … just before the owner and his two young boys took the front door off its hinges and ate their first meal on it (an ancient Norse custom), the Nazi Messerschmitts blew this house and all in it to hell.[8]

Reynolds seems to have pursued with vigour his career as designer-artist for more than fifteen years. An article in Harper’s Bazaar, 1932, placed him in Majorca seeking design material:

Majorca may not be peaceful for long as its attractions are being broadcast by returning voyagers, such as George Copeland who took a house there last summer, entertaining many amusing people including James Reynolds who acquired new ideas – especially for colors – to use for his stage sets and décor.[9]

Reynolds abandoned this all-consuming career in favour of full time writing and painting. As he put it himself, ‘the theatre in New York nearly drawing and quartering my interests.’[10]

Career in Literature

His career as author and travel writer can be traced by his literature, which seems to have commenced in 1937, in Ireland. Indeed, an obituary in the St Louis Post-Dispatch placed his birth there:

James Reynolds, American author and artist, died of a heart attack Monday at a resort in Bellagio, Italy, where he had spent his summers for the last 20 years … Born in Ireland, he was 65 years old and divided his time between Ballykillen and New York City.[11]

The obituary revealed that his book, Ghosts in Irish Houses, led to a series of books on the supernatural. Ghosts in Irish Houses, published in 1947 and inscribed to his Norwegian friend, Count Frederick Eric Von L, was, according to the book, commenced in ‘Ballykileen, Co Kildare’ on 9 October 1937 and completed at Laurel Hill, Province of Quebec, on 22 October 1946, a period straddling the Second World War.

The dust jacket stated that Ghosts in Irish Houses had followed his first book, Paddy Finucane A Memoir (1942), dedicated to Aviation-Cadet Gurdon Woods ‘for days spent roaming the American continent,’[12] and A World of Horses (1947), dedicated to ‘a young sportsman, Melville Church III.’[13]

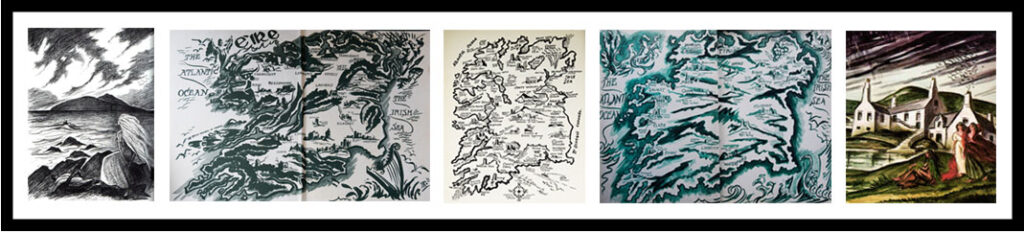

The author was described as stemming from ‘the ancient Gaelic story-tellers,’ an apt description, for Ghosts in Irish Houses is as much a book about Irish folklore as it is ghosts, and is full of cryptic, often tantalising, clues about the houses and people he visited in search of material. An artistic ‘ghost map’ drawn by the author pinpoints the location of the tales, the county of Cork featuring greatly in this work.[14]

Reynolds’ travels are recorded here and there by way of anecdote. In a tale about Co Sligo, he describes how he was crossing the Atlantic from New York to Galway in 1932 when he met on board the steamer Charles Tyrell, Professor of History at Notre Dame. In a tale about Kerrigan’s Keep, he took the Queen of Galway from Cobh to Ballyvaughan where he stayed in Mrs Anna Grogan’s Mariner Hotel. He obtained the tale of Drumnacrogha from ‘Mr Coney’ who he met in Drogheda in the house of Gaelic scholar, ‘Sir Teague Gorland.’

In 1936, Reynolds was introduced to ‘Patrick Gaisford,’ a descendant of Moyvore, who agreed to meet him at Baldoyle the following week, where Reynolds’ ‘big rangy gray chaser, Dragonstown’ was running in The Luttrellstown Stakes.[15]

Ghosts in Irish Houses was followed by Andrea Palladio (1948), Gallery of Ghosts (1949) and Baroque Splendour (1950). In 1951, 1952 and 1953, Reynolds returned to the subject of Ireland with The Grand Wide Way, A Novel; Maeve, the Huntress A Novel and James Reynolds’ Ireland.

In 1954, he published Pageant of Italy for which he won an award.[16] A review of the book described it as a tonic to ‘forget our gloomy skies’:

It would be difficult to imagine a more companionable guide than this writer. He has studied the history of Italy so minutely for so many years that it pours from him in an effortless stream, always the right anecdote for the right occasion. He has made the Italian language his own. He is intimately familiar with the country since childhood. His mother was a friend of Queen Elena and as a small boy he stayed for two nights in the Palazzo Reale in Naples as the Queen’s guest. His family owned a villa outside Lucca at one time and his boyhood hero was Glover dei Medici.[17]

A review of his next book, Fabulous Spain, published in 1955, suggested the work was funded by the Spanish Tourist Department.[18] Sovereign Britain appeared in the same year and included a chapter about ‘The Coastline of Wales and Northern Ireland deeply carved by the Irish Sea.’ It was dedicated to ‘Robert and Thebe Bell my cherished friends, who are inveterate travellers of the wide world.’ Reynolds was writing then from Mellerstaine, Firth of Forth. He described, in the introduction, a compulsion behind his writing and travels, an awareness or sense that he was accompanied always by the ghost of history, and was ‘part of a pageant of the centuries.’ As he eloquently puts it:

These preserved or fragmentary castles, cathedrals, abbeys, fortresses, manor houses, even the little, shy villages where cottages hug each other closely under thatch or slate, are the voice of the country. They are its heartbeat, the ancient clos-rolls of its history.

Reynolds also remarked on his education, evidently received in Ireland, and the impression made upon him on one occasion by a question from his tutor:

My schoolmaster in Ireland once surprised me into action by asking point blank, ‘Reynolds, who were the Picts?’ I was floored. Then and there I vowed not only to find out all I could about the mysterious Picts, but what there was to know about those who came before the Picts.

A review of his next book, Ghosts in American Houses (1955) offered a glimpse of his lifestyle:

The Laurel Room at Rich’s Store in Knoxville was the scene of an autograph tea given Wednesday afternoon by Mr and Mrs Thomas Berry of Fairfax in honor of their Yuletide house guest, James Reynolds, Irish artist, author and lecturer. This is the twelfth volume from the pen of Mr Reynolds whose brush created the charming murals on the walls of the spacious dining room at Fairfax … of especial interest to East Tennessee is the fact that this most recent book was brought to fruition at Fairfax where the intimate and charming introduction was penned on November 1, 1954.[19]

The review also added a little biography:

An only child, Mr Reynolds inherited the palatial estate of his grandfather in Ireland where he keeps vast stables of pedigreed horses and to which he returns frequently for brief visits after flying trips to all parts of the world. Most interesting of his recent appointments was the series of lectures given at the University of Tehran, Persia, where the chair of Romance Languages was endowed many years ago by his grandfather.[20]

Another return to Irish subject matter, More Ghosts in Irish Houses, appeared in 1956, inscribed to Hal Vursell, its foreword written at ‘The Endless Mountains Lodge, Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania, April 14, 1956.’[21] A ‘ghost map’ accompanied stories from around Ireland – including a number from County Kerry – and a note on the dust jacket described ‘a profusion of tempting stories … a collection for connoisseurs of the fine things of the book world.’[22] On the back of the dust jacket appeared a photograph of a man standing at ease beside a wall, identified from photographs in A World of Horses as the author.

Panorama of Austria would be his last book. It appeared posthumously in late 1957; reviewers in England and Ireland appeared to be unaware of the author’s death:

One either takes to Mr Reynolds in a few pages or one will never like him as a writer of travel books … he is a widely travelled man, a painter, a keen theatre-goer and a historian. He is a pleasant if talkative companion for an armchair tour of the Continent … Above all, Mr Reynolds is an expert at unearthing the unusual … English travel writers may omit any reference to Irish connections with Austria; Mr Reynolds does not. Even in his introduction he pays tribute to the work of the Irish monks in our golden age … Elsewhere we get the story of an Irish bishop of Salzburg, Virgilius O’Farrell, who, long before Columbus, proclaimed that the world was round and not flat.[23]

Almost a decade later, his Irish writings perplexed a journalist:

I have just finished a rather curious book, Ghosts in Irish Houses by James Reynolds, which was published in the United States in 1947 and may be purchased in nearly every leading Irish bookshop at the present time for a fraction of its original price of 12 dollars. The book is curious in that not only have I never heard of the majority of stories, but some of the places named are also unknown to me.[24]

A Wild ‘Ghost’ Chase

Ultimately, a biography of sorts can be formed from a closer study of Reynolds’ literature because as shown above, during the period 1947 to 1957 inclusive, he issued at least one book annually.

He was working on Ghosts in Irish Houses from 1937 as well as, it seems, the war effort when, in 1942, his friend, RAF fighter pilot and Wing Commander, Paddy Finucane, lost his life. As he wrote in his book about the pilot:

Well do I remember the last time I saw him. We had dinner together in a Greek restaurant, came out into the shadows of Soho Square under a London street lamp, said good-by, I off to Dublin, he to Richmond in Surrey where his family lives.

Reynolds recalled how on that occasion Paddy had remarked:

Do you know, even the big green shamrock – my fighting shamrock I paint on my plane – probably won’t save me for long. All I ask of St Kevin is that I’m cut off clean – no ragged ends.

‘I am glad he plunged into the waters of the English Channel and never appeared again,’ wrote Reynolds, ‘it was a hero’s death, sharp and clean … may the thousand sons of Poseidon, who are the waves of the sea, bear him gently to the shores of Ireland, and lay him in a gleaming cave in the Bay of Kinsale.’[25]

In 1943, Reynolds was ‘working in hospitals for war wounded throughout America’[26] and at one period during the Second World War, gave a series of talks – ‘Chalk Talks’ – which came at the request of Mrs Suydam Cutting (at whose hospital for the Merchant Marine he was working). Mrs Cutting asked what was to be his subject and he replied, ‘Horses-Horses-Horses’ – which turned out to be the most popular talk.[27]

An Art Exhibition in New York in 1943 put his paintings to good use:

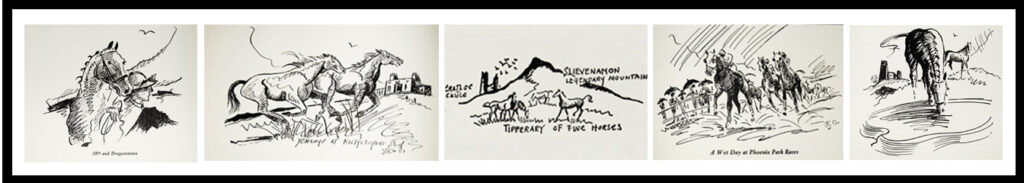

St Paul’s Guild, 115 East 57th Street, a collection of recent paintings by James Reynolds has been installed for the benefit of the Cathedral Canteen. Mr Reynold’s Irish allegiance manifests itself in a series of dashing studies of Irish horses and horsemanship; and his equal loyalty to America shows itself in a long record of color and typical American barns, stretching from Vermont to Louisiana, and with of course, an especial enthusiasm for the barns of the fox-hunting people of Virginia. Mr Reynolds is an inveterate decorator and his designs have a bravura that is irresistible.[28]

The end of the Second World War was the beginning of a golden decade of literary output for Reynolds, his works offering a glimpse of 1930s Ireland and indeed his travels during that decade. At the time of his residence in Co Kildare, he was deeply involved with horses. As his book on the subject reveals, ‘Reynoldstown was bred at Major Furlong’s demesne, not far from where I lived, Ballykileen in County Kildare.’ A description of the dual Grand National winner of 1935 and 1936 shows intimate knowledge:

I had always been very fond of this dark-brown horse. He had a witty eye, a grand way of moving across country, and a miraculous way of flying his jumps. At one time, I fully believe Reynoldstown and Shannon Power, an Irish Free State cavalry horse, were the most perfect jumpers in Ireland.[29]

He sketched the Irish steeplechaser, Newtownmountkennedy at Tramore Races in 1936[30] and threw a dinner party for friends from America, Italy and Austria who had travelled to Ireland for the Dublin Horse Show. After dinner, his friends were incredulous when he suggested that the stallion join them ‘for sugar’:

What followed had been carefully rehearsed by Bingo Lacey and myself. I whistled, waited a moment, then whistled again … a patter of little hooves along the marble of the terrace drew nearer and nearer out of the darkness. There, blinking a little in the lights from the drawing-room, his big, liquid eyes peering out from behind a ridiculously bushy forelock, stood Thunderer, a Shetland-Orkney Island pony stallion, all 8 hands of him … no larger than a good-sized St Bernard.[31]

In 1936, he was also in India, for he describes a scene witnessed in Udaipur when a flock of hungry eagles and falcons fed on pomegranates, and he vowed to one day paint the scene:

Suddenly, like all good things in my life, a chance conversation with a friend from California brought this dream of painting a ceiling of falcons and pomegranates instantly into focus. In the house of Richard Hanna, in Burlingame, California, it is now an accomplished fact, and most surely the most exciting decoration I have ever painted.[32]

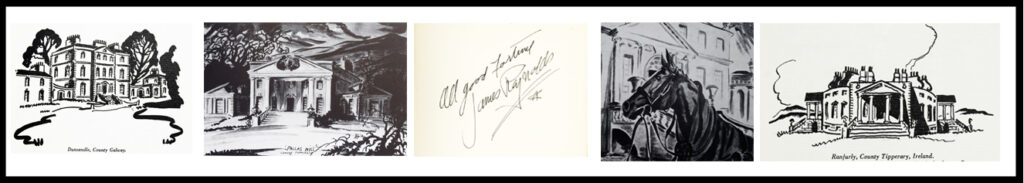

Though not published until 1948, Andrea Palladio And the Winged Device was ‘Started Vicenze, Italy, April 12, 1946’ and ‘Finished Castle Davan, County Donegal, October 20, 1947.’[33] It was dedicated to ‘Russborough, Blessington, County Wicklow, Ireland, the First House in the Palladian Style to Capture my Imagination. All the years of my Life it has held First Place in my Interest.’[34]

It is a work of exceptional interest in terms of its history of architecture in Europe and America, but also for its intimate content, explained by Reynolds thus: ‘Over a period of twenty years or more, I have had access to many diaries, letters, and notes written by persons of the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Many are in the possession of my own family. Others have been shown me by friends, from private collections.’[35]

The book is divided into five parts, the first to an inspired biography of Palladio, followed by sketches of architecture in Ireland, England, Europe and America.[36] Indeed, Reynolds steps well beyond the bounds of Palladian, and Palladian-influence, to cover a vast amount of architectural ground.

His section on Ireland is in some respects a lament for the demise of the Great Houses in Ireland. It opens with ‘Palladio’s Spirit in Ireland’ and includes such buildings as Ballyscullion, Co Antrim, Pallas Hill, Tipperary (with photographs of both) and Castlecoole, Co Fermanagh, ‘more Hellenic museum than dwelling house.’

A chapter is devoted to architect Richard Castle, disciple of Palladio, how he went to Dublin, and his influence on the city and beyond. Another chapter on the townhouses of Dublin is an historical and architectural tour of the city. As he concludes himself, ‘Now we might all in the lovely spring weather take a walk around Dublin.’

Reynolds veers well off subject in a chapter about Irish country houses (and often their owners) – like Mount Pallas in Co Limerick – to the utter benefit of the architectural historian. Here he describes Pallas Hill in Co Tipperary:

A house of infinite moods crowning the ridge of a sloping rise which is in reality the first foothill of Slievnamon, the Gaelic ‘Mountain of the Sleeping Woman,’ this gracious house commands one of the most spellbinding views in all Ireland. The house has many features which ally it closely with the pavilion farmhouse type of building so often designed by Palladio when he was left to his own devices.

A remark about Captain William George ‘Bay’ Middleton (1846-1892), equerry to Earl Spencer, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, suggests the house under his observation was associated with ‘Bay’s’ parents, George Crawford Middleton and Mary Margaret Hamilton:

In the black and yellow marble hall a magnificent bust of Pallas Athena, helmeted and wearing her scaled aegis, tops a black marble pillar at the foot of the stairs. This was sent to the mother of Bay Middleton by the Empress Elizabeth of Austria on one of her Italian visits and gave the house its name.[37]

‘In Russborough,’ he writes, ‘we have everything. All the best of Vitruvius, Palladio, and Richard Castle’:

In 1751, Joseph Leeson of Dublin was in Rome, later Venice. He drove in a huge painted coach along the Brenta Canal as guest of the Mocenigo. Here he saw for himself the same inspiring Palladian villas that had so captured the imagination of his friend Leinster, ten years before. If Leinster could build a vast Dublin house and extravagant Carton at Maynooth, he could top the two by building on his gently undulating fields near Blessington in County Wicklow such a spellbinder of a house that it would be the talk of Ireland, and farther, for years to come.[38]

Another chapter, ‘Fires of Beltaine,’ describes the ‘lonely, dishevelled, forgotten houses built in the ‘grand wide days’ of Ireland’s prosperity, roughly between 1700 and 1808’:

Often one comes upon these hidden houses, crouching in the midst of demesnes so choked by rhododendron thickets, fifty feet in height, that the once whitewashed walls are frescoed by damp and mold, streaked in yellow, brown, and green, a veritable temple to mildew.

‘To find out why the houses were ever built in such inaccessible places,’ he continues, ‘even from the owners, is to draw blank’:

County Sligo; lovely Donegal of wide valleys and green pastured hills; Connemara, stark, like some Attic kingdom; County Galway, ever loved by me, having spent enchanted years among its beech groves and turf-crowned headlands; Little Mayo, reaching farther than one thinks. All harbor lost houses.[39]

Here and there, the author’s dialogue is punctuated with anecdote:

In my New York flat I have a tall Venetian mirror … Ever since I bought it in Venice many years ago. It has virtually governed my life. The wall it hangs on must be at least sixteen feet in height. I raised the roof of the room where this mirror hangs – literally raised it – five feet when I designed the alternations of the flat from scratch. Greyhounds of sette-cento Venice crouch upon the fern-wreathed pediment of this mirror. What gives it distinction, a delightful Commedia dell’Arte touch, is the fact that the tails of the greyhound are floriated and cascade down the sides of the mirror in garlands.[40]

In his chapter about European architecture, Reynolds makes a rare reference to his father:

I first saw the gigantic hunting-lodge, Caserta, when I was ten years old … I was so flabbergasted by the overpowering barracks of this pink and yellow Palazzo del Re that I shouted, ‘What is it?’ My father told me it was the largest house in the world. I believed him.[41]

Discoursing on Caserta, he writes:

An Irish traveler named Darley wrote to Horace Walpole: ‘Descending from my coach at the Gate of Royal Caserta, I was instantly choked by the white dust of the vile Neapolitan roads, churned to clouds by lackeys, foot-boys, postilions, and the wheels of every class of horse-drawn vehicle which from dawn to dawn dash to and fro between Naples and this Bedlam in Marble.’[42]

Though many houses feature in Reynolds’ chapter on America, he described as ‘impossible’ the task of cataloguing the hundreds of Palladian or Palladian-influence houses scattered about the Southern and Northern states. One house he does include is Windsor Lodge, no doubt because of its near location to North Cliff, Rixeyville, Virginia – which as will be seen was the home of his godchild.[43] A chapter on Thomas Jefferson is another included:

Until three years ago, Poplar Forest, a few miles from Lynchburg, Virginia, was owned by Mr Hutter. One day his son Christian Hutter drove me from Charlottesville to Poplar Forest to show me the house … When Thomas Jefferson and his family lived there in its full flower, it was as near Utopia as will ever be seen in this world, according to his letters to his wife when he was forced to be in Washington.[44]

Reynolds was in Ashintully, Tyringham, Massachusetts – destroyed by fire in 1952 – when his World of Horses was published in 1947. Indeed, he included this ‘one real Palladian house in the North,’ a ‘sheer Irish Palladian house,’ in Andrea Palladio:

It has a Gaelic name as well: Ashintully, the House on the Hill … Ashintully is owned by John McLennan.[45]

In his acknowledgments, especial thanks were extended to the late Lady Helen McCalmont of Thomastown, Kilkenny, to Mrs Bushnell Cheney, Mrs Melville Church II, and the Contessa Zano, to Courtland Smith Esq, and to Daniel Lavezzo, Jr.[46]

His love for his grandfather in Ireland is openly expressed:

A cool and bracing breeze from off the sea a mile off and a half away to the West, an elderly man and a boy of about ten walked swiftly along the ridge of an upland pasture in the County of Limerick in Ireland. At a glance, the most casual observer could see that there was a deep affection and understanding between the two. Had the observer hazarded to guess the relationship between the man and the young boy he would probably have said that they were grandfather and grandson … The guess would have been right.

‘In all our nineteen years together,’ adds Reynolds, ‘during which he meant more to me than did anyone else alive, I never knew him to suggest a plan that, when he fulfilled it, was not even more satisfying than it was in anticipation.’[47]

Elsewhere, he informs his readers that:

I was brought up with Irish jumpers, steeplechasers, and hunters, and I have for many years bred these horses. I know every fibre and tendon in their big, rangy bodies. As we Irish say, they are ‘my heart of corn.’[48]

He discourses on hunting in Ireland, describing it as ‘no namby-pamby sport’:

One gets plenty of all kinds of hazards. I always feel the same way about fox-hunting in Ireland, which I have done in every Irish county where there is a pack, as I used to feel about parties in Rome in the great wide days before 1939. Contessa Zano would give a ball with a band and an orchestra from Vienna to play the waltzes. The food was straight from Olympus … Legion are the fox-hunts across the green and springy turf of Irish counties that I shall remember all the days of my life.[49]

In late 1947 and into 1948, Reynolds was in Italy and England, as revealed in Gallery of Ghosts ‘Started at Castello di Bracciano, Lago di Bracciano, April 15, 1947 … Finished at Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, October 9, 1948.’ ‘In telling my Irish ghost stories,’ he writes, ‘I tried to paint a cool, silvery-gray atmosphere, for they are legends of an ancient race, highlighted by emerald stretches of sea and mountain, with a bright stain of blood upon white marble stairs or lichen-covered stone.’

In this work, dedicated to ‘Emily North Church (Mrs Melville Church II), Virginian, whose interest in the history and secrets of old houses marches with my own,’ with a foreword by Lon Chaney, his selections were gathered from further afield:

Having spent most of my life, both boyhood and adult, traveling to the farthest reaches of the world, I have had many extraordinary opportunities to add to my folios of ghostly lore. Out of those folios I have chosen nineteen, from ten countries spread over the world: England, France, Belgium, Portugal, Italy, Saxony, India, Norway, Hungary, and America.

He adds, ‘Because I was schooled at an early age in the excitement, triumphant color, and pageantry of the ghost story, as told by my paternal grandmother, a very priestess of the art of storytelling, the theme has always held my interest, flexibly, but nonetheless strongly.’[50]

Baroque Splendour, ‘a compendium of an opulent century’ and dedicated to Edna James Chappell ‘For Years of Graceful Friendship,’ was published in 1950.[51] It was ‘Started at Schloss Moritzburg, Forest Moritzburg-Dentel, Saxony, May 29, 1948’ and ‘Finished at Villa Serbelloni, Lago di Como, Italy, October 10, 1949.’ A chapter devoted to Ireland 1720-1787 describes three prevailing styles of architecture:

As one drives past country houses in any of the Irish counties, it becomes apparent that only three styles of architecture prevail: feudal castles (Killeen Castle and Malahide are ancient strongholds), Palladian, and Georgian. There are a few scattered Regency (1800), and in Cork there are one or two Charles II houses.[52]

A run of Irish titles occupied Reynolds in the early 1950s, the first two of which were novels: The Grand Wide Way, published in 1951, was dedicated to Alice Keating Cheney, ‘whose ancestor, Baron Keating, of Moorestown Castle, County Waterford, lived notably in the Grand, Wide Way.’[53]

It was described as a novel of manner – a manner of living, of thinking, or giving and taking:

This is a book of characters …and the people in this book live in the Grand Wide Way. They are the Irish sporting gentry, hunting, shooting, fishing and riding, living on the land – if not the fat of it – in gracious white country houses or half-ruined houses.

Maeve The Huntress was a continuation of the above, published in 1952, and dedicated to Mary Margaret Church of North Cliffe, Rixeyville, Virginia, ‘I lift a stirrup cup to good hunting with the Warrenton, or in any country where she follows hounds.’[54]

Rixeyville, as already noticed, was the home of his godchild:

If I were asked to name the house in America that has given me the warmest welcome … it would unhesitatingly be North Cliff, near Rixeyvllle, Virginia … Not the least of the charms of North Cliff is that Mrs Melville Church II, the renowned horsewoman Emily North King to her legion friends, runs a singularly well-appointed breeding stable.

‘The son of the house,’ Reynolds continues, ‘the bright and shining Chucky, now in his middle teens, is my godson, and young Mary Margaret Church is a budding Diana huntress, so North Cliff has special meaning for me.’[55]

One of his most revealing titles, James Reynolds’ Ireland (1953) offers clues about his background. It is evident from this work, dedicated to Dorothy Quick, ‘a kindred spirit in the writing of romantic tales and ghostly lore,’ that Reynolds moved in high circles.[56]

Its foreword places Reynolds at ‘Ballygaltee House, County Galway, 1952’ (a name which appears to be fictional) and describes a childhood in Ireland, and love and admiration for his paternal grandfather ‘so great … he constituted my whole universe.’

According to the ‘ghost map’ illustrated in the book, his grandfather, John Reynolds, lived somewhere between Inchigeelagh in Co Cork and Adare, Co Limerick, in a residence Reynolds called ‘Croghangeela, Rathgannonstown.’[57]

One day, at the age of eleven and with his grandfather’s approval, Reynolds ventured out alone to explore the countryside and rest the night at ‘Clareville Castle.’ This first solitary walk, during which he sketched a Co Limerick farmhouse, was a defining moment in his life, and gave him the taste for solitude to develop his artistic talents. His choice of subject, a building, was his first in this category for until then he had only sketched horses, notably thoroughbreds, his first love:

Long ago I decided that the three things I like best in this world are horses, houses and people and in that order.[58]

His first horse, Defender, was a gift from his grandfather when he ten years old. Indeed, his childhood seems to have been occupied with his parents and grandparents at race meetings and horse fairs.

At age sixteen, he found he was unwittingly ‘married’ to a Romany girl and though he made a quick getaway, he encountered the girl a number of times over the years during his rambles in Ireland.[59]

On his twenty-first birthday, he was presented with an elaborate sketchbook decorated in his established racing colours to record race horsing incidents. Instead, he used the book to write about Dublin, and the Wide Street Commission promoted by William Robert Fitzgerald, 2nd Duke of Leinster. This however he abandoned:

My reason for not continuing was not the one that thwarted the duke. His was a dissolute, ruthlessly profligate son who, though promising his father on his deathbed to carry on his idea to remodel Dublin, did not do so. In my case it was ghosts, Irish and otherwise, and the theatre in New York, nearly drawing and quartering my interests.[60]

By way of redress, Reynolds devotes a chapter of his book to Dublin, drawing in Maude Gonne, Lady Wilde and her son Oscar, and Lady Gregory, as well as buildings like Smock Alley and other Irish playhouses.[61]

Reynolds was commissioned by various people to paint for them, and on one occasion stayed at Parknasilla, Co Kerry en route to Valencia Island where he was to paint two horses belonging to a friend.[62]

Pageant of Italy appeared in 1954, dedicated to Robert and Margalo Gillmore Ross, ‘Remembering the times we have met in Italy and watched its pageantry pass by.’[63] In his acknowledgments, penned at Manor House of Issogne, Val d’Aosta, Reynolds paid tribute to Daniel Lavezzo for ‘driving me about the Liguria, to see villas and castellos, frescoed and jammed with furniture representing all the notable Italian periods.’

Of Italy he writes:

I have lived in Italy for varying lengths of time since early boyhood. Italy is in my blood. My senses as a painter and a writer respond …I come to Italy because the daily round, the grace of living here, appeals to me.

Remarking on mosaics at Pompeii:

My favourite is a large rectangular panel featuring a brace of gorgeously plumaged cocks … I made a painting of this mosaic for my bedroom of Ireland where the exciting sport of ‘Cocking’ is followed with enthusiasm.[64]

Fabulous Spain, inscribed to Margaret Mower, ‘Traveler in Spain, whose interest in all that is Spanish marches with my own,’ followed the Italian compendium, in 1955.[65] In this lavish travel guide, which concluded in Fuentarrabia, Reynolds gives a rare anecdote about his mother:

I remember once, after a tour of El Escorial, when I was about twelve years old, my mother asked me what I thought of the riches I had seen and why I had glowered so at the broody canvases covering the walls. I answered her, ‘Acres and acres and acres of canvas, but all so dark I couldn’t make out what the pictures were.’ In her usual crisp manner she replied, ‘The pictures are dark, surely, but look closely next time, exert your imagination. It will surprise you.’[66]

The subject matter did not deter him from referring to Ireland:

In Dublin I once picked up a small, tattered book on a stall in front of a musty old second-hand shop in Ashton Quay. Bound in leather, the book had once been brilliant red. That was probably what first caught my notice. Flipping over the pages, my eye was caught by the opening words of a chapter. ‘And so we came to Ronda, on its stupendous gorge.’[67]

Once again, Reynolds found space to mention his grandfather. His remarks were made in a chapter on Madrid to where he had first travelled at age twelve:

Of all my remembrances, what has remained clearest in my memory is the answer to a question I received from my grandfather Reynolds, whose opinion on anything under the sun I considered unassailable. The evening before I was to leave Rathgannonstown in Ireland to journey with my mother to the Spanish capital, I asked, ‘Shall I like Madrid?’ My grandfather lifted a small magnifying glass which he habitually wore on a black moiré ribbon around his neck. Using it as a quizzing glass he looked sharply at me and delivered, straight thrust, ‘Why wouldn’t you now? Madrid has everything.’[68]

Panorama of Austria was Reynolds’ last book, issued in 1957, the year of his death. It was completed at Schloss Rabenstein, Frohnleiten, Styria, and dedicated to Sally Jones Sexton, ‘of Bryn du Farm, Widely Traveled Friend, Notable Horsewoman.’[69]

Barely two pages into the book, Reynolds turns to Irish history:

In the golden age of Irish faith and learning, monks from the monasteries of the Western Isles traveled into Austria and along the Danube to Switzerland and Bavaria, bringing the light of faith with them. All over Austria, in remote mountain villages or the busy market towns of the valleys … the work of these Irish monks survives.[70]

The following captures his style. The island of Herrenchiemsee ‘is a dream of surpassing richness that literally stuns the mind’:

The State Bedchamber baffles description. It surpasses magnificence. The great four-post bed raised as on an altar is surrounded by a heavily carved golden balustrade, an ‘impassable’ barrier. The bed stands on a purple velvet carpet embroidered with great brio, in a pattern of golden sunbeams. The curtains weigh three tons, so heavy is the padded velvet ablaze with gold thread embroidery. Frau Jörres, an embroideress with twenty women to assist her, worked for nine years on the embroidered bed curtains and spread alone.[71]

‘In all the world,’ he writes, ‘there is no sight to compare with the open-face, terraced iron mines of Erzberg.’ In the village of Mönchshof, he witnesses a mother reprimanding her six year old son, and was particularly taken by the boy’s attire:

The coat-of-arms of Burgenland Province was emblazoned on the back of his jacket. Against a yellow shield, a fiery red eagle, tongue protruding in defiance, wore a crown of gold Crusaders’ crosses. The wings outstretched, each pinion alert, this was a ponderous amount of heraldry, it seemed to me, to plaster on the back of so small a boy, no matter what his mischief.

Reynolds later learned that the boy’s name was Stani, a notorious runaway ‘whose wanderlust overtook him.’ On this most recent occasion, the boy had been found by a lorry driver in the middle of the night wandering in a village in Lower Austria:

In desperation his mother had recently taken a festival banner bearing the arms of Burgenland, embroidered on it Stani’s name and village and his proclivities for wandering, then stitched it to the only jacket the boy possessed.[72]

The reader is left to wonder about Stani, and also to ponder on where the author might next have taken his readers. Death, however, put an end to a decade of informed and informative reading of the most cultivated and lavish style in the post war years.

Raising Ghosts

Reynolds certainly dined with the great and good, though many identities are masked by fiction. However, some are not, like Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), with whom he dined in Galway during Mrs Woolf’s summer holiday there. She was the first to tell him the legend of ‘Mad Mag of the Sorrows’ of Achillbeg Castle, whose six brothers were entombed on Achillbeg Island:

A long retaining wall still in fair state of preservation runs for five hundred yards along the side of Achillbeg Island facing the mainland. At one end is a tall square tower, now a gigantic aviary in effect, for thousands upon thousands of sea birds make nests in the craggy stone work. Inside one of the walls stands one of the glories of twelfth century Irish architecture: a unique multiple sarcophagus in carved stone … Each brother is walled up beside an effigy of himself.[73]

Another friend was Edith Anna OEnone Somerville (1858-1949), co-author (with her cousin, Violet Florence Martin) of Reminiscences of an Irish R.M. (1899). Reynolds enjoyed various outings to her home, Drishane House, Skibbereen, Co Cork (which in his book he gave the fictional name of ‘Tally-Ho House’) and found one particular story by Edith, The Cherry Bird, entrancing. Edith later sent him the story, but before his letter of thanks had a chance to reach her, ‘my dear friend was dead’:

The recent death of E OE Sommerville not only removed from the Irish scene a woman whose magic tongue for witty narrative simply floored her listeners, but left a niche in the hearts of her countless friends never to be filled.[74]

In 1952, Reynolds attended a coming-of-age party at Luggala House for national hunt jockey, Gay Kindersley, son of Lady Oranmore and Browne, thrown by Mr Kindersley’s grandfather.[75] He describes how the Spanish Consul got lost on the way and ‘ended up at dawn in Rathdrum twenty miles away.’

On another occasion Reynolds spent the night on a heap of flour bags in the loft of a cotteen in Connemara. The next day, he watched, fascinated, as the man of the house packed butter into lugghs to be sunk into the bog for refrigeration.

His artistic eye was, he said, trained to register detail at a glance, which he called upon to paint the ghost of Stella Dunn who he encountered in Grafton Street, Dublin. Reynolds learned more about the ghost of Stella Dunn a few years later while staying with friends during the summer race meeting at Kenmare.[76] Stella, wife of an officer of the Irish Fusiliers, was a successful opera singer who toured the world until she settled in ‘Cartymore Abbey’ in Kerry to have her first child, a son. Tragically, she became addicted to drugs and was found murdered in Soho.[77] Her body was returned to Cartymore and buried in a crypt under an old chapel, ‘as are all the Dunns of Cartymore,’ since when her ghost had haunted the building.

James Reynolds’ Ireland concludes with recollections of old racehorses, like his cousin’s chance find (and purchase of) a long coveted original sketch in oils of Isinglass (great-grandsire of Blandford) out of Oslet.[78] He also remarks that he was once the owner of the stallion, Old Radnor, which at the time of his writing was at Castletown Stud, Ballylinan, Co Kildare.[79]

A description of his room at ‘Ballyshilty Stud,’ in which his grandfather was once part owner, includes a self-portrait with one of his racehorses. Writing about this stud, Reynolds quotes from an old stud book in the tack room:

This day Gandaro’s ship arrived from Cadiz. We brought ashore a Spanish Barb stallion sired by our great Barcaldino. Named Canto, he will stand at Ballyshilty and enrich the strain.[80]

The Ghost of James Reynolds

The dialogue of James Reynolds’ literature suggests that in the period he was writing, he was relatively well known. He dined well, put up in smart hotels, or the homes of his countless hosts, and seems to have had extraordinary access to what might be considered the out-of-bounds. A sense of luxury, privilege and ease pervades the whole, yet the production of fourteen self-illustrated books and other writings in one decade is a breath-taking undertaking accomplished only by hard work. And yet more than sixty years on from his death, he seems to be almost unknown, as elusive as the ghosts he loved to write about. His many references to Ireland suggest an intimate acquaintance with the country, particularly in his references to his grandfather:

Mary Moriarity, an old retainer at my Grandfather Reynolds’ house Rathgannonstown, remarked coldly when asked if she would like to take a short spin in his claret-red Renault, the first motorcar of its kind in Ireland, ‘I’d not at all, thank yer honour; sir, I’d meet death at the crossroads surely in that divil’s velocipede.’[81]

More than once he mentions his grandfather’s demesne at Croghangeela, Rathgannonstown, but the location of this fictional address in his accompanying ‘ghost map’ points to a house without a name in Cork, Limerick or perhaps Tipperary.

His Kildare residence was ‘Ballykileen’ which he mentions frequently, with different spellings. It is anyone’s guess if the name is authentic. ‘Reynoldstown,’ he remarks in World of Horses, ‘was bred at Major Furlong’s demesne, not far from where I lived, Ballykileen in County Kildare.’[82] On a few occasions, he describes Ballykileen as near Castledermot. ‘When in Ireland, I go very often to Galway, motoring from my own house near Castledermot in County Kildare.’[83]

In James Reynolds’ Ireland, he describes the manner in which he opens his post, and adds:

This elaborate procedure went on twice a day at Ballykilleen when the yard boy had returned with the post from Castledermott, the nearest village.

This suggests a residence closer to Carlow than Kildare but as it stands, it is a residence unidentified.[84]

The Ghost of History

Fortunately, the search has been narrowed a little with the help of Tralee genealogist, Marie Huxtable Wilson, who has carried out extensive research. The report of Reynolds’ death in Italy identified a number of his intimates.

Those informed of his death by telegram were Harold Vursell, his publisher, and Daniel Lavezzo, 154 East 54th Street, New York City, where Reynolds kept his home-cum-studio. In 1950, a few paragraphs in Baroque Splendour described how he had taken up occupation there:

Many years ago I was asked to do the stage settings for Charles Dillingham’s production of the Lonsale comedy The Last of Mrs Cheney. I wished to show on the stage, to set off properly the radiance of Ina Claire in the same part, a great Palladian house in England, the like of Hackwood Park, Holkham, or Heveningham Hall.

Pondering on where in New York he would find the proper furniture, a friend introduced him to Daniel Lavezzo:

Mr Lavezzo, whose extraordinary perception in all regarding the beauties of Italian sette cento decoration is equalled, I have found, only by his friendliness, motioned to the stairs. ‘Many more rooms above.’

Finding what he needed for the production, Reynolds ‘promptly asked Mr Lavezzo if I could have a studio in the building’:

I spend a great deal of time in Europe traveling, painting, writing, and with my horses. But each time I return to New York I bring masses of document on the myriad matters of the daily round that interest me … Yearly the room has grown in dishevelment and interest, a kind of kaleidoscope of loot. The room is awash with memories of years of work, completed, and stacked with plans for more to come.

The death certificate also identified a relative, Margaret Reynolds, sister-in-law, 28 Cambridge Street, Huntington Station, Long Island, New York.[85] Margaret Reynolds was Margaret Pauline Cerney (or Cserney), wife of Gerald Ahira Reynolds.[86]

Gerald, son of John J W Reynolds and Carrie Sophia Eldredge, was born in New Jersey on 8 October 1896.[87] His brother was Harold Warren or Harold Warner Reynolds, born in New York on 22 October 1891 – otherwise known as ‘James.’[88]

It is probably worth noting here that an illustrator named James Warren Reynolds of 618 N142d St, New York, born 22 October 1894 at Warrenton, Virginia, seems to have been confused with the above.

The father and mother of Harold and Gerald Reynolds were born in Kentucky and Pitcher, Chenango, New York, respectively, and had been living in New Jersey and New York before their premature deaths in 1903 and 1907.[89]

This would explain Reynolds’ frequent references to the influence of his grandfather in his childhood. But it does not lend to an Irish background because American Census records indicate that his grandparents – John is the only name Reynolds gives in his literature – were also natives of Kentucky.[90]

Harold Warner/Warren Reynolds, otherwise James, died at the Grand Hotel, Villa Serbelloni, Bellagio, Como, Italy from ‘Cerebral Ictus’ on 21 July 1957. He was buried at Cimitero Comunale di Bellagio, Bellagio, Provincia de Como, Lombardia, Italy.

So much is known about Mr Reynolds, the ‘Irishman.’ It may be that he was, after all, a first class storyteller who subsumed stories about Ireland into a fictional guise. If this was so, he did it remarkably well. And yet there is an authenticity in his relationship with his grandfather and an almost inherent knowledge of the country that suggests otherwise.

When I was about twelve years old, I used to have long talks with my grandfather about horse breeding, the thousand and one points which must be kept always in mind, a clear, sound circle of planned thought. He would say …’[91]

His access to private correspondence written ‘by persons of the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries,’ much of which was in the possession of his own family, and even his frequent references to English artist Sir Joshua Reynolds, raise interesting questions about his background. The distance between truth and fiction in his claims to Irish ancestry, however, will only be narrowed with more detailed research of American records.

In the meantime, the last word might go to one of the author’s English friends, who kept a wooden box containing Reynolds’ postcards and letters from all over the world. It was engraved, ‘Cache J. R.* He Got Around.’[92]

Works

Paddy Finucane A Memoir (1942)

A World of Horses (1947)

Ghosts in Irish Houses (1947)

Andrea Palladio (1948)

Gallery of Ghosts (1949)

Baroque Splendour (1950)

The Grand Wide Way, A Novel (1951)

Maeve the Huntress, A Novel (1952)

James Reynolds’ Ireland (1953)

Pageant of Italy (1954)

Fabulous Spain (1955)

Sovereign Britain (1955)

Ghosts in American Houses (1955)

More Ghosts in Irish Houses (1956)

Panorama of Austria (1957)

The following articles published in The Atlantic Monthly are also attributed to James Reynolds: The Laughing Laundress February 1951 pp57-60; The Midnight Spinners April 1951 pp42-45; Dublin for the Horse Show August 1951 pp54-56; The Tower A Story January 1952 pp64-68; Slippers that Waltz till Dawn A Story June 1952 pp70-74; Galway Great Week July 1952 pp61-63; The Muted Harp A Story August 1953 pp68-71.

______________________