Formerly one of the largest landowners in the whole of Ireland, the Earl of Desmond’s territory was devastated by the English. At length, all his castles fell into their hands[1]

By 1581, the Earl of Desmond had taken to the woods for protection from the Elizabethan forces. For a time, he maintained a considerable following, his supporters evading capture in the mountains of Kerry. He took refuge where he could in his many castles, not least among them the Island Castle (Castleisland).[2]

His strongholds, however, were reducing in number, as revealed in a letter written by Sir William Drury to Walsingham in 1579:

The Earl of Desmond and his brothers campe within a mile of each other; meet together and secrete resorte as some thinke of the principals, and no inmite between their people. Some of the castels whereof the Earle offerred soldiers to reside for this service are since raised.[3]

In June 1581, Desmond was encamped at Aghadoe Castle[4] near the borders of Lough Leane, Killarney but was surprised during the night by Captain Zouche en route from Dingle to Castlemaine:

The earl and all those who were with him were at this time buried in deep sleep … The captain immediately and alertly attacked all those whom he found standing in the streets, and slew them without mercy.[5]

From there, Desmond proceeded to Castlemaine, where on 15 June, Zouche made a surprise attack and killed over 60 men. The Earl escaped with difficulty.[6] He had by now suffered the loss of Dr Saunders, the Pope’s legate, who died in a miserable hovel in the ‘moods (sic) of Claenglass’ worn out by cold, hunger and fatigue. Desmond had been offered a pardon if he would give up to them this eminent ecclesiastic but this he steadily refused. The place of Dr Saunders’ death differs in the historical record but it appears to have occurred in about April 1581.[7]

From mid autumn 1581 to the end of 1582, Desmond, the ‘rebell of Mounster’ continued in conflict[8] in an area extending from Fineen’s Ridge, to Aherlow, to Kilmallock, though he made an incursion into Kerry in the autumn of 1582.[9]

In all the wide territory of Desmond not a town, castle, village or farmhouse was unburnt … in six months more than 300,000 people had been starved to death in Munster, besides those who were hung or who perished by the sword[10]

He plundered the territory of Ormond, defeated the English in a hard fought battle at Gort-na-Piei (Peafield in Tipperary) and cut to pieces a large force which had been sent against him by the brother and sons of the Earl of Ormond at Knockgraffin. He also despoiled the MacCarthys.[11]

He was encamped in the glen of Aherlow when Lady Desmond surrendered to Grey in June 1582, though Queen Elizabeth ordered that Lady Desmond be sent back to her husband, ‘unless she could induce him to surrender unconditionally.’

I would rather forsake God than my men – The Earl of Desmond

As the end of 1582 approached, Desmond, not daring to stay in one of his castles, spent Christmas with his countess in a wood near Kilmallock. He was attacked at daybreak by some soldiers which caused him to ‘run out of his bed in his shirt and stand up to his neck in a river under a bank with his lady and by this means he escaped.’[12]

By early 1583, Ormond was ‘systematically beating his way through the great wood of Harlow’ in an effort to drive Desmond back into Kerry. Desmond, who was harbouring in the woods of Kilcowrie near Kilmallock, was described as ‘a houseless wanderer, flitting from one fastness to another.’[13]

Many a long and weary night did he spend wandering through the bogs and mountains, deprived of the common necessaries for himself and the few retainers who clung to him[14]

In April, he was in Port Castle, Abbeyfeale, from where he wrote, on April 28 1583, to Sir Warham St Leger, ‘ I might have more justice, favour, and grace at her Majesty’s hands when I am before herself than here at the hands of such of her cruel officers as have me wrongfully proclaimed.’[15]

With a price on his head, Desmond’s followers had been reduced greatly in number.[17] In August, the garrison of Kilmallock learned that Desmond was in Aherlow wood, and slew sixty of his gallowglasses. A month later, he was beset in Duhallow but escaped on horse. He was driven towards Sliabh Luachra.[18]

At the beginning of November, his chief supporter, Captain Gowran MacSwiney, was killed, reducing the earl to ‘greater extremities than ever.’[19]

His own immediate attendants consisting only of a priest, two horsemen, and a boy, he was obliged to wander form place to place, hiding from the ever-watchful spies anxious to claim the price on his head. Closely pressed by his pursuers, he was hunted from Limerick to Kerry with the indefatigable Captain Dowdall of the English army upon his heels.[20]

Hounded and Cornered

Winter of 1583 upon him, with but four persons to accompany him from one cavern of a rock or hollow of a tree to another, Desmond harboured about his old stronghold, Earl’s Castle, or Desmond’s Castle, at Ballymacelligott.[21] As the long nights set in, ‘the insurgents and robbers of Munster began to collect about him, and prepared to rekindle the torch of war.’[22]

On 9 November 1583, ‘the Earle left the woods near the Island of Kerrie (Castle Island)’ and went ‘westward beyond Tramore to Doiremore (Derry More) Wood near Bonyonider.’ Plundering ‘forty cowes’ upon his way, his whereabouts were betrayed.[23] He was tracked by a party of soldiers sent from ‘Castle Mang’ to Ballyore, and thence by moonlight towards ‘Glaunageentie at Slieve Loughra.’[24]

‘Glaunageentie’ (Glanageenty) – Valley of Weeping – was to be the scene of Desmond’s death:[25]

They tracked him like bloodhounds during the darkness of the night and on the 11th November 1583, they all making a greate crye, entered the cabbin where the Earle lay … himselfe sayinge, ‘I am the Earle of Desmond! Save my lyfe!’[26]

At this moment, John MacWilliam and James MacDavid were the only companions in the hut with Desmond.[27] In his last moments, however, he was deserted:

The few horsemen basely took to flight and the Earl was alone and stripped. A soldier, whose name was Daniel O’Kelly, smashed his right arm with a stroke of his sword, and then cut off one of his ears with a second blow. This miscreant then dragged him out, and being apprehensive lest any might come to his rescue, brutally separated his head from his body. Thus perished Desmond in the 25th year of his earldom.[28]

Faithful to the Last

In the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, Desmond’s pedigree is given thus:

Garrett, the son of James, son of John, son of Thomas of Drogheda, son of James, son of Garrett of the Poetry, son of Maurice (the first Earl of Desmond), son of Thomas of the Apes, son of John of Caille [Callainn], son of Thomas (in whom the Fitzgeralds of Kildare and those of Desmond meet each other), son of Maurice (ie the Friar Minor, who died 20th of May 1257), son of Gerald, son of Maurice Fitzgerald.[29]

Ardnagragh Castle was described as the principal Castle of this branch of the Desmond FitzGeralds.[30] Fitzgerald, a kinsman from the castle, faithful to the last, stole the headless body of Desmond by night from the wood where it had been thrown by Kelly and Moriarty and laid it in the old Fitzgerald burial place at nearby Kilnananima.[31]

Thomas Fitz David Gerald of Ardnagragh, who had entered into the rebellion, was also killed. In 1584, his castle and lands were forfeited.[32]

___________________

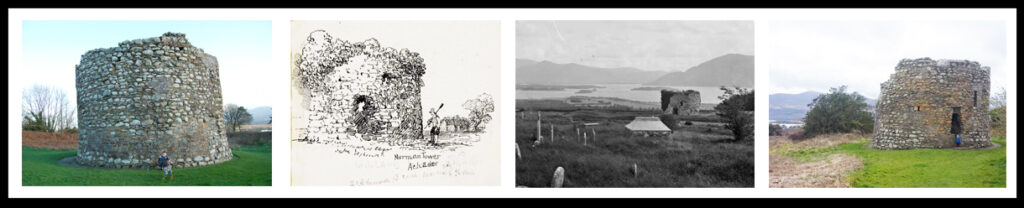

[1] Pierse The Pierse Family (1950) by John H Pierse, p97. ‘The castle of Askeaton which was the last Desmond stronghold to hold out, surrendered in April 1580 ... The plunder of cattle was essential in order to feed the troops. On one such occasion in April 1580, 200 infantry and 50 cavalry were ambushed in the woods by the Maige by 200 rebels ... the rebels were defeated and about 60 of them killed. Captain Walker, with the ward of Adare which comprised 300, was met about a mile from Adare by the Earl of Desmond with 80 horses and 600 infantry. The Earl and his troops were forced to retire with the loss of 60 men and five horses ... The following August the troops of the Earl of Ormond were attacked by the Geraldine rebels at Adare Castle and were forced to flee’ (‘The Desmond Rebellion’ by Laurence Dunne and Jacinta Kiely, Eachtra Journal (2013) Issue 16, p16). [2] The Annals of Innisfallen AD 1215 record how Maurice McThomas M’Gerald had built castles at Dunlow (Dunloe), Kilforgla (Killorglin), at Mainge (Castlemaine), at Molahiff (Molahiffe) and at Calanafercie (Callinafercy). The following records the fate of the ‘Island Castle’: ‘Sir Thomas Noreys (Norris) vice-President of Munster, writing to the Privy Council from Cork in late December 1598, reported that ‘the traitors there … purpose to break down the Abbey of Tralee, the Castle of the Island (Castleisland) and to burn the town of Dinglecush with all other buildings fit to receive any garrisons’ (Romantic Hidden Kerry (1931) by T F O’Sullivan, p67). A few years later, the Castle of the Island had perished: ‘On the 23rd August 1600, Carew reported the taking of Lord Fitz Morris’s house ‘called Lixnaw’ and of Rathonyne Castle belonging to the bishop of Kerry; that ‘Edward Denny’s house at Tralee was utterly defaced, nothing being left unbroken but a few old vaults; and that the Island of Kerry, ‘the ancient and chiefest house of the Earl of Desmond, and later belonging to Sir William Herbert as an undertaker, and almost all the Castles in these parts are razed to the ground by the rebels.’ [3] ‘There is general determination to rase the town of Dingell, lest Ormond should posses it and make their staple there’ – letter from Sir William Drury to Secretary Walsingham (‘History of Muckross Abbey,’ Kerry Sentinel, 9 October 1897). [4] Otherwise styled Parkavonear or Parkavoneen Castle. [5] Aghadoe Church A Celtic Christian History (c1997) by Mark Garavan, p22. ‘Teige MacDermot MacCormac MacCarthy of Coshmaine was killed in the skirmish. His lands were attainted and reverted to the Crown, bringing to an end this important sept whose centre was the nearby castle of Molahiffe’ (Houses of Kerry (1994) by Valerie Bary, p2). ‘Also they say that Tiegue Mac Dermod MacCormac MacCartye late of Malahive [Molahiffe] aforesaid, gentleman, on the second of November in the twenty-first year of our said Lady the Queen entered into rebellion with the said Gerald late Earl of Desmond aforesaid against our said Lady the Queen, and that being in rebellion on the twelfth of June in the twenty-second year of her reign he was killed in rebellion near Aghadoe’ (‘Inquisition of 1584,’ Kerry Archaeological Magazine (1910), No 5). ‘A battle seems to have taken place at Aghadoe in the year 1581 when the Earl of Desmond, who was encamped there, was surprised by Captain Zouch, who had been sent by Elizabeth to govern the County. Desmond was defeated and forced to retire to County Limerick. It is probably in this action that Teigue McCarthy was killed’ (ibid). The ruin of this thirteenth century Norman castle is found opposite the Aghadoe Heights Hotel near the viewing point. Aghadoe is a place of archaeological and ecclesiastical interest. Further reference, Aghadoe Church A Celtic Christian History (c1997) by Mark Garavan. A round tower stands in the vicinity of the nearby Aghadoe Cathedral; see ‘Notes on the Round Towers of the County of Kerry’ by Richard Hitchcock, Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, Vol 2, No 2 (1853) pp252-254. [6] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-earls-of-desmond-in-castleisland/ [7] Lenihan described Claenglass, or Caenglass, as situate in the south of the county of Limerick, with adjacent woods of Kilmore, ‘his companion in misfortune, the Bishop of Killaloe, who attended him in his last moment, escaped to Spain and died in Lisbon AD 1617’ (‘Fate of the Earl of Desmond,’ History of Limerick; Its History and Antiquities (1866) by Maurice Lenihan, pp109-125). Smith, in his History, described Saunders’ miserable death ‘of ague and flux’ in the woods of Clonigh (Tullygarron): ‘About three miles to the N. E. of Tralee, stands Tulligarron belonging to Rich. Chute, Efq near which place, Saunders the pope's nuncio, who was sent over in 1579, with a consecrated banner, and the pope's authority to curse and bless, at his will and pleasure, all such as assisted or resisted the rebels who opposed Q Elizabeth’s government, died miserably of an ague and flux, brought on him by want and famine, in the wood of Clonlish, in 1582.’ A correspondence, St Leger to Burghley, June 3, 1581, suggests that Saunders died about the beginning of April (‘The Desmond Rebellion’ 1579-1583, Ireland Under the Tudors (1890) by Richard Bagwell MA, Vol III, chapters 37 to 39). ‘Just before Ormonde’s dismissal became known, his enemy, Sir Warham St. Leger, told Burghley that he lost twenty Englishmen killed for every one of the rebels. But famine and disease succeeded where the sword failed, and in the same letter St. Leger was able to announce that Dr. Sanders had died of dysentery. For two months the secret had been kept, his partisans giving out that he had gone to Spain for help; but at last one of the women who had clothed him in his winding-sheet brought the news to Sir Thomas of Desmond. Since the fall of Fort Del Oro, he had scarcely been heard of, and had spent his time miserably in the woods on the border of Cork and Limerick. Some English accounts say that he was out of his mind, but of this there does not seem to be any proof. All agree that he died in the wood of Clonlish, and it seems that he was buried in a neighbouring church. His companion at the last was Cornelius Ryan, the papal bishop of Killaloe.’ Desmond’s adviser Saunders, the pope’s nuncio, ‘after wandering for two years in the woods, a wretched fugitive, was found dead and mangled by beasts’ (True Stories from the History of Ireland (1829) by John James McGregor, p267. Further reference to Dr Saunders, otherwise Nicholas Sanders or Sander, of Surrey, http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-earls-of-desmond-in-castleisland/. [8] ‘The rebell of Mounster hathe his cheif haunte, in the woodes of Arlowe, and omulrians countreye, bothe being not farre of, from Lymerick’ (Allegory, Space and the Material World in the Writings of Edmund Spenser (2006) by Christopher Burlinson, pp176-177). ‘Arlowe’ = the glen of Aherlow, Galtymore. Many spelling variations, including Aharlo woddes and Harlow. ‘It seems that Arlo was notorious as a hideout for Irish bands who were believed to be joining the Desmonds in rebellion’ (ibid). [9] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (1848, Vol III) translated by John O’Donovan, p1783. ‘The Earl of Desmond remained from the middle month of the autumn of the preceding year [1581] to the end of this year [1582] between Druim-Finghin [Fineen’s Ridge, ridge of high ground extending from near Castle Lyons, Cork to Ringoguanagh, on south side of Dungarvan, Waterford], Eatharlach [Aherlow, four miles to the south of Tipperary] and Coill-an-Choigidh ... In the autumn of this year [1582] he made an incursion into Kerry and remained nearly a week encamped in the upper part of Clann-Maurice.’ [10] Romantic Hidden Kerry (1931) by T F O’Sullivan, p54-55. [11] ‘Fate of the Earl of Desmond,’History of Limerick; Its History and Antiquities (1866) by Maurice Lenihan, pp109-125. [12] The Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry (1756) by Charles Smith, p275. [13] Selections from Old Kerry Records (1872) by Mary Agnes Hickson, pp120-121. ‘He was obliged to wander about in a miserable condition, for, not daring to lie in any house or castle, he frequented the woods and fastnesses’ (The Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry (1756) by Charles Smith, p275). The woods of ‘Kilcowrie’ were evidently Coill-an-choigidh, otherwise Kilquaig or Kilguaig, near Kilmallock. ‘And such was the condition of the once mighty Desmond that he was obliged to keep Christmas in the wood of Kilguaig, near Kilmallock. He was here surprised, and saved himself by rushing out of the hut in his shirt, and standing with the countess up to his chin in water’ (The Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Persecution of the Irish Catholics (1847) by Daniel Daly, translated by Rev Charles Patrick Meehan, pp107-110). John O’Donovan, in the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (Vol 5), notes, ‘Coill-an-Choigidh (the wood of the province shown on old maps of Munster as Kilquegg, a short distance to the south of Kilmallock, heeding or caring for neither tillage nor reaping, excepting the reaping [ie cutting down] of the Butlers by day and night in revenge of the injuries which the Earl of Ormond had up to that time committed against the Geraldines’ (p1783). [14] The Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Persecution of the Irish Catholics (1847) by Daniel Daly, translated by Rev Charles Patrick Meehan, pp107-110. [15] By The Feale’s Wave Romance of Thomas, Earl of Desmond and Catherine McCormack A Legend of Port Castle, Abbeyfeale (2018), p17. Letter in full http://danton.us/the-desmond-rebellion-1579-1582/3/. [16] James Stark Fleming (sometimes given as James Sturk Fleming) was born in Stirling, Scotland, in 1834. He worked as a solicitor but had a deep interest in archaeology and art. He was ‘a constant visitor to Ireland and during his stay here he makes a study of the antiquities and historical remains of Ireland and is a familiar contributor to the quarterly Journal of the Society of Antiquaries of Ireland of which he is a member … The sketches are all excellent, and they are fifty in number, and in addition to the author’s wide travels in this country represent a good deal of research amongst old prints, engravings, drawings and paintings for pictorial records of these monuments of the fighting age that do not exist any longer’ (Freeman’s Journal, 30 August 1914). A review of his book, The Town Wall Fortifications of Ireland in the Belfast Newsletter, 19 September 1914 (the year of its publication) described the progress of his work in antiquarian matters. The book followed another, Ancient Castellated Structures of Ireland published in 1911: Town Wall Fortifications of Ireland is the result of a number of visits to this country extending over many years. His original intention was to contribute an article to the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Irish Society of Antiquaries of which he is a member but as his sketches accumulated and no work on this branch of the castellated architecture of Ireland appears to have been published, he came to the conclusion that the collection with relative notes in book form would be favourably accepted by Irish antiquaries as a contribution to the national archaeological literature. James Stark Fleming married in 1867: ‘At 88 North Castle Street, Edinburgh on 14th March 1867 by the Rev James Stark, Well Park Free Church, Greenock, uncle of the bridegroom, Mr James Stark Fleming to Agnes, eldest daughter of Mr Francis McKenzie.’ Two daughters were born at Stirling, the first on 20 April 1870 and the second on 14 March 1871. A son, Francis Fleming, was born at Stirling on 30 December 1872 (he died on 9 August 1937 and was buried in Logie Cemetery). Mrs Agnes Mackenzie Fleming died at ‘Inverleny,’ Callander, on 31 March 1912 aged 73. James Stark Fleming died in Stirling on 9 October 1922 and was buried in Logie Cemetery. The following obituary is taken from the Strathearn Herald, 14 October 1922 and Scotsman, 11 October 1922: The death has taken place at Stirling of Mr J S Fleming, of Messrs Fleming & Buckanan solicitors, in his 88th year. He was a native of Stirling. Mr Fleming was well known as a writer on archaeological subjects and as a pen-and-ink artist. He published several books, illustrated by himself, dealing with the old streets, wynds, and courts of Stirling. Mr Fleming was an FSA (Scotland) and a member of the Stirling Natural History and Archaeological Society. Among J S Fleming’s publications relating to his native place, The Old Ludgings of Stirling (1897) Old Nooks of Stirling (1898) Ancient Castles and Mansions of Stirling (1902) The Old Castle Vennal of Stirling (1906). It is worth noting that in 1909, Mr Fleming submitted a paper on ‘Irish and Scottish Castles and Keeps Contrasted’ – on the motion of Count Plunkett it was agreed to refer it to the Council for publication, duly carried out in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (Irish Independent, 31 March 1909). [17] ‘Gerald, Earl of Desmond, on the 25th Day of September in the 24th year of our said Lady the Queen by ordinance of law was attainted’ (Romantic Hidden Kerry (1931) by T F O’Sullivan, p56). [18] The Fall of the House of Desmond by Sister Margaret Mac Curtain, p42. ‘In the beginning of July 1583, Ormond passed over Sliabh Luachra through Castleisland and Castlemaine and thence into Dingle to cut off Desmond’s escape by sea.’ [19] The Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry (1756) by Charles Smith, p275. Gowran (or Goran) MacSwiney was killed on 1 November 1583. [20] Pierse The Pierse Family (1950) by John H Pierse, p97. [21] Houses of Kerry. Further reference, http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-lost-castles-of-the-mcelligotts/ [22] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (1848, Vol III) translated by John O’Donovan, p1795. ‘He had but four persons to accompany him from one cavern of a rock or hollow of a tree to another, throughout the two provinces of Munster, in the summer and autumn of this year [1583]. When the beginning of winter and the long nights had set in, the insurgents and robbers of Munster began to collect about him, and prepared to rekindle the torch of war. But God thought it time to suppress, close, and finish this war of the Geraldines.’ [23] ‘It unfortunately happened that those who were sent to seize the prey, barbarously robbed a noble matron and left her naked in the field. When the fact came to the knowledge of her kindred, they collected a party of men and, led by a foster-brother of the earl, approached his hiding-place. I know not whether with the intention of taking his life, or avenging the injury done to their sister’ (The Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Persecution of the Irish Catholics (1847) by Daniel Daly, translated by Rev Charles Patrick Meehan, pp108-110). [24] ‘The Last Geraldyn Chief of Tralee Castle’ by A B Rowan, reproduced in Selections from Old Kerry Records (1872) by Mary Agnes Hickson, pp117-130. ‘He was concealed in a hut in the cover of a rock in Gleann-an-Ghinntegh (Glan-geenty, five miles east of Tralee). This party remained on the watch around the habitation of the Earl from the beginning of the night until the dawning of day; and then in the morning twilight they rushed into the cold hut. This was on Tuesday, which was St Martin’s festival. They wounded the Earl, and took him prisoner, for he had not with him any people to make fight of battle except one woman and two men servants. They had not proceeded far from the wood when they suddenly beheaded the Earl. Were it not that he was given to plunder and insurrection, as he [really] was, this fate of the Earl of Desmond would have been one of the principal stories of Ireland’ (‘Fate of the Earl of Desmond,’History of Limerick; Its History and Antiquities (1866) by Maurice Lenihan, pp109-125). [25] ‘Gleann-an-Ghuintigh, where the Earl of Desmond was assassinated, is in the parish of BallymacElligot, and about five miles to the west of Tralee. P O’Sullivan translates the Irish name Vallis Cunei’ (The Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Persecution of the Irish Catholics (1847) by Daniel Daly, translated by Rev Charles Patrick Meehan, pp108-110). [26] Pierse The Pierse Family (1950) by John H Pierse, p97 and ‘The Last Geraldyn Chief of Tralee Castle’ by A B Rowan, reproduced in Selections from Old Kerry Records (1872) by Mary Agnes Hickson, pp117-130. [27] ‘At this moment there were the Earl Garret, John MacWilliam and James MacDavid – these were the only companions who partook of his miserable hut at the time of his death. Cornelius O’Daly and a few others were at a short distance from him in the valley (Gleann-an-ghuinntigh), watching the cattle that had been seized the day before. Had O’Daly been present he would not have deserted his lord at the crisis, as did the aforesaid two, and far be it from me to glory in my relationship to him who was faithful from beginning to the end. I would not, for the sake of O’Daly, cross the boundaries of truth. Whatever I have written I have had from those who are trustworthy, and many books and manuscripts. Let no one, therefore, accuse me of vanity; but let me do justice to O’Daly – he was a brave soldier, ever faithful to his lord, and so truly patriotic that, when all was lost, he preferred his honour and reputation to any compromise with the queen. Had he been recreant to his principles he might have saved whatever property he owned; but in the Irish parliament held after the wars of the Desmonds, it was forfeited to the crown, as may be seen in the acts then passed; he was thrice arrested by Ormond, and honourably acquitted’ (The Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Persecution of the Irish Catholics (1847) by Daniel Daly, translated by Rev Charles Patrick Meehan, pp108-110). [28] Pierse The Pierse Family (1950) by John H Pierse, p97. See ‘Last of the Earls of Desmond’ on this website: http://www.odonohoearchive.com/last-of-the-earls-of-desmond/. ‘Daniel Kelly an Irishman, then a soldier, (who was afterwards hanged at Tyburn [for highway robbery], but for this service, was rewarded with a pension of 20l for thirty years) almost cut off the old man’s arm with his sword’ (The Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry (1756) by Charles Smith, p276). ‘Owen O’Moriarty was also hanged some years after, in the insurrection of Hugh O’Neill, by FitzMaurice of Lixnaw, the family having become excessively unpopular on account of the part they had played in this tragic occurrence’ (History of Limerick, p112). ‘The Earl of Desmond fell, not by the hand of Kelly, but by that of Donald McDonald Imorietaghe’ (The Literary Gazette and Journal for the year 1830). [29] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (1848, Vol III) translated by John O’Donovan, p1795. [30] ‘Ardnegragh (the height of the plunders) was the principal Castle of that branch of the Desmond FitzGeralds, known in history as the ‘Aicme’ or Sept or ‘Clonn in-trincha, the clan of the Cantred. From these two designations comes ‘Trucha-an-aicme’ now the name of the Barony of Trughenackmy. The site of the Castle and the ‘Pike’ of Ardnegragh are pointed out in the townland of Cordal East and Parish of Ballincashlane’ aforesaid’ (‘Inquisition of 1584 (concluded),’ Kerry Archaeological Magazine (1910), No 5 – continued from issue No 4, same year, transcribed and annotated by W M Hennessy). Further reference, http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-fitzgerald-castles-of-cordal/. [31] Bary (Houses of Kerry), p13. [32] ‘Thomas Fitz David Gerald late of Ardnegraghe in the said County of Kerry, gentleman, on the second of November in the twenty-first year of our said Lady the Queen entered into rebellion with the said Gerald late Earl of Desmond, and that being in the rebellion aforesaid on the sixth of November in the twenty-fourth year of our said Lady the Queen, he was killed near Cosseleye in the said County of Kerry, and that at the time of his entering into rebellion and at the time of his death in rebellion he was seised in the Lordship as of fee in the castle, townlands, tenements and hereditaments of Ardnegraghe aforesaid’ (‘Inquisition of 1584 (concluded),’ Kerry Archaeological Magazine (1910), No 5 – continued from issue No 4, same year, transcribed and annotated by W M Hennessy).