In June this year (2024), Castleisland District Heritage was contacted by Beth O’Leary Anish from Massachusetts, scholar of Irish American literature, who was travelling to Ireland to attend a meeting of the American Conference for Irish Studies in Limerick. She was hoping to fit in a visit to Castleisland where her great grandfather, James Leary of Dromultan, was born in 1860. Family lore had handed down stories about James including one about activity during the Land War, the period during which James left Ireland. Beth was anxious to learn more.

Beth was put in contact with Tom Brosnan, a member of the committee of Castleisland District Heritage, who has knowledge of the Dromultan district. They met there on 17 June 2024 and Beth found Tom to be an excellent guide. Tom’s own research also benefitted. He discovered that Brosnihan Square, Worcester, Massachusetts is named after a grandson of Molahiffe farmer Daniel Brosnan,[1]

Following her tour of the Castleisland district, Beth conceded that though she was unable to find proof of her great grandfather’s involvement with the Moonlighters, ‘the facts of time and place do line up quite well with my father’s claim.’[2]

Beth was invited to tell her story. It is one that may resonate with countless others around the globe.

James Leary of Dromultan: A Story of the Land War

By Beth O’Leary Anish

‘1887 they left … but generations march on’

As a child growing up in Massachusetts in the 1970s and 1980s, I took pride in knowing where my Irish-born grandfather was from. To anyone who asked where my people were from in Ireland. I would say, “Castleisland, County Kerry.” No matter that Grandpa O’Leary had died almost twenty years before I was born, or that he was only a toddler when his parents brought him over to the United States.

Most people of Irish descent in my generation were at least fourth generation Americans. Their grandparents (and mine on my mother’s side) were grandchildren or great-grandchildren of the millions of Irish who came over to the States during and just after the Great Hunger. I was one of the few people my age who could name a direct tie to a specific place in Ireland, even though we had no known relatives remaining there. Being able to name Castleisland as a place associated with my family meant the world to me.

As a student at Boston College I was thrilled to find out that my professor, Phil O’Leary, was from Worcester, Massachusetts like me, and that his people were from Kerry. I rushed up to him after the first class to see if we might be related. I told him my O’Leary family was from Castleisland. His people were from a different part of Kerry, but having traveled to Ireland frequently, he told me with confidence that Castleisland was known for good bread. I have yet to confirm this description, but it stuck with me as one more small fact to cling to until I could get there myself.

Really, I knew next to nothing about Castleisland. I did not know where it was in Kerry, and I could not have, at the time, named where Kerry was in Ireland. I knew nothing of the Irish language, which everyone around me growing up called Gaelic if they spoke of it at all, and I had no idea why my great-grandparents James and Sarah (Moriarty) O’Leary had taken their toddler son to America in 1887.

From about my senior year in high school and throughout my time at Boston College, I set out to learn as much about Irish literature and history as I could. I began to know more about Ireland in a general way, but nothing more about my family.

Before my husband and I began having children I had one request: I wanted to take my first trip to Ireland. We did so in 2000, planning a stop in Castleisland into our itinerary. We walked around the town with no idea of what we were seeking. We had no address to visit, and no living relatives I would have known. We found a church with a few O’Leary religious buried in its small graveyard. We left and continued on our tour of Killarney and Dingle. At least now I could say I had stepped foot in the town.

A few years later, a cousin of my mother’s shared with us the results of her research into the Ferris family, my mother’s paternal side. They hailed from Derry (Ferris/Ferry) and Louth (McNally). My mother’s great-grandmother, Bridget McNally, had a curious story. She had emigrated to America, married another Irish immigrant, and raised a family in the mill towns of central Massachusetts in the second half of the 19th century. None of that was odd. What was odd was that she returned home to Termonfeckin in County Louth, where she died in a river in 1890. She left her family back in Massachusetts, the children all grown by this time. Family lore says that she had a photograph commissioned of the family before she left. When I heard this story I was fascinated. Eventually it moved to the back of my mind while my husband and I welcomed two children of our own.

One summer evening, while taking a walk after the children were in bed, I started thinking about Bridget’s story. Why did she her leave her family? How did she drown? Was it intentional or accidental? By the time I returned from my walk I had started filling in the gaps of what I knew with my imagination. I sat on the couch and began to write. A year later I had completed a novel based loosely on my great-great-grandmother’s life and death.

My parents were among the first readers of the book. My mother was great at catching a typo here and there: shall instead of shawl, and waive instead of wave. My father’s reaction, I thought, was more comical. He liked to tease a little bit, especially if he thought my mother was receiving more attention than he was. For this reason, I laughed when he said, “why didn’t you write about my family?” When I asked, “why would I?” he said, “my grandfather was a gunrunner for the IRA.” Unfortunately, thinking it a joke, I did not ask him to elaborate on this new piece of information about his grandfather O’Leary.

I had never heard him mention such a thing, or much of anything about his grandfather, at that point. My father did not seem particularly tied to Ireland, beyond a surname that clearly marked us as being of Irish descent and his staunch defense of his Catholic faith. He occasionally whistled or sang a few words of Irish-American tunes that would have been popular as he was growing up in the 1920s and 30s. One day on a New Hampshire beach, looking at the Atlantic from the American side, I asked him if we could see England from here and if we were at all English. He said, “I guess we all are, in a way.” He added something about all of us speaking English now. Knowing what I think I know now, this would likely have his father and grandfather spinning in their graves.

In the last several years of his life, I spent more time with my father than any point since I was a young child. As a college English professor, I had some flexibility in my weekday schedule, and was able to bring him to most of his treatments for an aggressive form of skin cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma and rosacea were two things his doctors attributed to his Irish DNA. As a child he was red-haired, and he always possessed skin so white it was nearly translucent.

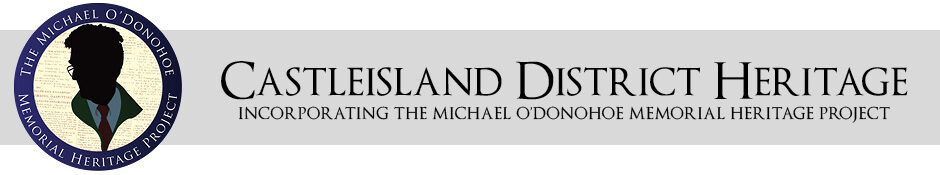

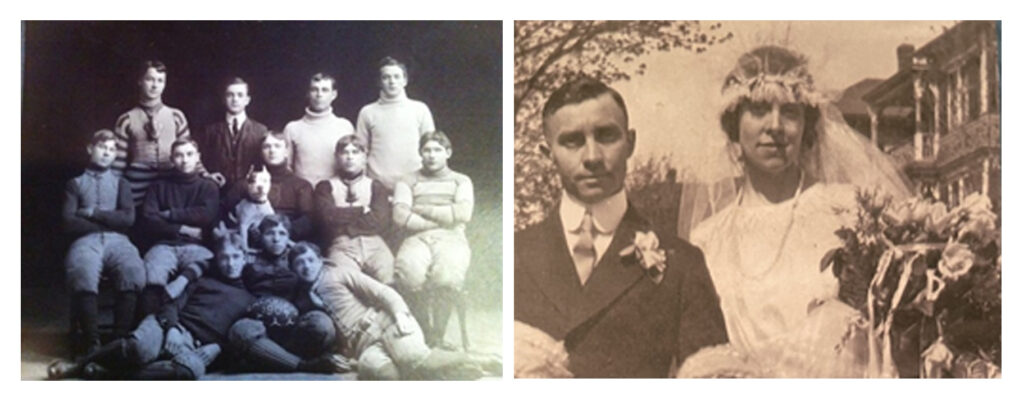

In my father’s later years I began to hear more about his father and grandfather. His family’s is an American success story. Dennis, the boy who would become my grandfather, gained several American-born siblings, learned to play baseball well enough to be offered an athletic scholarship to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, turned that down to learn the more immediately useful trades of plumbing and welding, became a machinist, and saved enough money to buy multiple parcels of land both within and without the city limits of Worcester. When his father became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1902, he became one, too. In his thirties he married Mary Ellen Laverty, she of a long-established Worcester Irish family that had been integral in bringing the first Catholic church to the city decades earlier. They had six children together, the only girl (also named Mary) becoming a nun and medical professional in the Sisters of Providence order. The boys either went to college and became teachers, or worked in respectable trades as carpenters and phone company men. They were all solid Catholics, and good people.

Much of this I knew before the drives to cancer treatments, and the hours spent waiting for doctors and test results. Perhaps in his nineties my father became more nostalgic, more forthcoming with stories of his upbringing, or I took the time to listen. He shared the story of learning to drive with his father and grandfather in the car. On one of Worcester’s hills he got nervous, stopped short and sent his grandfather’s false teeth flying onto the dashboard. He told me how when he was in his first year of college, his father and grandfather would pick him up and drive out to the little farm my grandfather owned just beyond the Worcester city limits. They would work on the farm, taking care of chickens and goats.

So far this is a Worcester story, but it has its origins in Castleisland. Dennis would never have married a Worcester woman and brought my father into this world if James and Sarah had not made the decision to come to America. For years I assumed that like so many Irish, they left their homeland to seek job opportunities and better financial futures for their children. Now I think there may have been more to the decision to emigrate.

Nearly twenty years after my father first dropped the “gunrunner” comment, I finally stopped to reconsider their story. In between I had gone back to school for a doctorate in English, with a focus on Irish and Irish-American literature. I set out to understand how Irish Americans tell stories about themselves, and how they fill in gaps where they cannot possibly know detailed facts.

In 2021 I published a book called Irish-American Fiction from World War II to JFK: Anxiety, Assimilation, and Activism.[3] At a party to celebrate the book’s publication, I spoke to a friend of a friend and her husband, a more recent Kerry immigrant to the U.S. Chatting with him later in the night, I mentioned my grandfather’s Kerry origins and my father’s “gunrunner” comment, still laughing at what I considered a joke. I said I knew the IRA, at least under that name, did not exist in 1887 when my family left Ireland. This Kerryman caused me to think differently. He said no, but there was Fenian activity and the Land Wars going on at the time, and he assured me the Castleisland area was quite actively involved.

It finally hit me, too late to ask my father who passed away in 2019, that I needed to find more details about his grandfather James and why he came to America. I had already learned that my grandfather, at least, was an Irish patriot from afar. I never knew why my father had been named Robert until well into his old age. It turns out he was meant to be named Robert Emmet O’Leary, but was named Robert Edward instead because my grandmother worried he would face prejudice in 1920s America. He was born in November, 1922. Now I wonder how closely his father and grandfather were watching events unfold at home, from the Easter Rising to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. What I do know is that the first three children born in his family were named for the Holy Family (Joseph and Mary) and Robert, for a martyr for Ireland’s freedom. I also know that Dennis went to City Hall in Worcester and restored the “O” in front of O’Leary. Records in Ireland and his immigration paperwork have James and the family listed as Leary.

These two facts tell me that my grandfather’s connection to Ireland, despite having been raised in America, was very strong. I imagine he learned that pride in being Irish at the knee of his father, whom I now have good reason to believe was a Fenian himself. Aside from that one statement of my father’s, the evidence is circumstantial, but some research assured me it is not far-fetched to think James was a “gunrunner” during the Land Wars of the 1880s.

Reading Donnacha Seán Lucey’s book Land, Popular Politics, and Agrarian Violence in Ireland: The Case of County Kerry: 1872-86,[4] I could hardly believe my eyes as page after page mentioned Castleisland as one of the most active areas of agrarian uprisings in the 1880s. Not only that, but Lucey explained how many of the young men involved in Moonlighting, going from house to house to gather weapons and enforce boycotts on lands vacated by evicted tenants, were second sons, or at least not the oldest in their families. Lucey even mentions the term “gunrunner,” a term that I now feel in hindsight my father would not have come up with on his own. It had to have been told to him that way. The pieces were starting to fit together.

Baptised in 1860 at Killeentierna parish, son of Denis and Catherine (Marshall) Leary, James Leary was of prime age and life prospects to have been a Moonlighter. Patrick Leary, his older brother, was baptised at Killeentierna in 1858. Given Irish inheritance laws, Patrick would have stood to inherit anything his parents had, while James would have to make his own way in life. James also fits the profile of a Moonlighter by being in his late teens and early twenties during the period of the Land War.

In 1884 and 1885, while agrarian outrages were climbing in Kerry in general and the Castleisland district in particular,[5] James married and became a father for the first time. His bride was Sarah Moriarty from Chapel Lane in Castleisland town. Together they moved to a cottage on the grounds of Annamore house in Dromulton. James was a laborer and Sarah a domestic servant. Sarah gave birth to my grandfather Denis in April of 1885. Two years later, in April 1887, they chose to move to America and settle in Worcester, Massachusetts.

The year of departure of James and Sarah is again circumstantial evidence for his involvement with the Moonlighters. Janet Murphy of the Castleisland District Heritage society pointed me to John Roche’s book Terryfaha,[6] which as she says , “documents vividly the many who fled the country during the 1880s to avoid incarceration and the death penalty if ‘suspected’ [of Moonlighting].”[7] As a young husband and father, James now had something to lose if he was incarcerated or executed, as even innocent men had been in his district of Dromulton.[8] By the time a new Crimes Act heightening policing around agrarian uprisings was instituted in the fall of 1887,[9] James, Sarah, and their young son Denis were safe in America.

Once in Massachusetts, James and Sarah had an additional five children. James continued to work as a laborer, now for a coal company. Sarah was a homemaker, sadly remembered by her grandchildren as being quiet and sullen. I wonder if Sarah, as I wondered about Bridget McNally on my mother’s side, suffered from depression after being disconnected from the rest of her family back in Ireland or wherever they landed in the world. Regardless, the family grew and generations marched on.

Both James’ and Sarah’s oldest son Denis (often spelled Dennis in later records) and their oldest daughter Mary, born in Worcester in 1889, married into the Laverty family of Worcester. Many of their descendants still live in and around Worcester, including myself and my own two children, most of my six living siblings, over twenty first cousins, and many nieces, nephews, and great nieces. I investigate and write this history both to satisfy my own curiosity about our roots and to preserve the findings for the rest of the family, who all hail, in some small way, from Castleisland. I also do it to honor my O’Leary ancestors.

I am deeply appreciative of the work done by the Castleisland District Heritage organization, with special thanks to both Janet Murphy and Tom Brosnan. Janet was my e-mail correspondent, who encouraged me follow up on this tiny bit of oral history I learned from my father. Though it was the thinnest of leads, and I cannot ever with certainty say my great-grandfather James was a Moonlighter, I can at least feel supported in my speculation by the history of the time and place where he came of age, the Irish nationalist bent of his son Dennis, and the words of his grandson Robert proudly proclaiming him “a gunrunner” for the Fenian cause.

In a happy footnote to this story, I made it back to Castleisland during a recent trip to Ireland. Tom Brosnan not only found the land records for the exact location of James’ and Sarah’s cottage on the grounds of Annamore house, but drove me there himself, along the way showing me where my O’Leary ancestors were likely buried at Kilsarcon, and where they would have socialized and gone to Mass at Scartaglin. “How are you at climbing fences?” is not something a middle-aged academic hears often, but I am so grateful for getting out into those fields behind Annamore, where two little cottages once stood by a well, and where my grandfather was born.

______________________________

[1] Tom Brosnan by email 18 June 2024. ‘Patrick Brosnan moved to Tralee and was father of John Brosnihan.’ [2] Beth by email to Castleisland District Heritage, 20 June 2024. [3] Anish, Beth O’Leary. Irish American Fiction from World War II to JFK: Anxiety, Assimilation, and Activism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. [4] Lucey, Donnacha Seán. Land, Popular Politics, and Agrarian Violence in Ireland: The Case of County Kerry, 1872-86. UCD Press, 2011 [5] Lucey, Land, Popular Politics, and Agrarian Violence, 175-76. [6] Roche, John. Terryfaha: Tears of Blood, 2023. See especially chapter 35 (353-55), which details men leaving the country to avoid being accused and prosecuted. [7] E-mail from Janet Murphy to Beth O’Leary Anish, 7 June 2024 [8] Several articles on the Castleisland District Heritage site detail the hanging of two innocent men, James Barrett and Sylvester Poff, for a murder they did not commit in Dromulton in 1882. [9] Lucey, Land, Popular Politics, and Agrarian Violence, 199.