‘Art is your proper friend’ – Thomas Davis

Castleisland District Heritage has received notification of grant aid from Kerry County Council’s Community Enhancement and Community Support funds (Department of Rural and Community Development). The funding is timely and has enabled the purchase of office equipment to continue recording and communicating the history and heritage of the Castleisland district.

The success of Castleisland District Heritage to date is reflected in a ‘virtual’ presence that extends to all corners of the globe, as evidenced by the correspondence we receive and the visitors who seek out our offices in the Island Centre, Main Street – visitors who have included this year Thomas Keneally of Schindler’s Ark fame.

The value of history and heritage is difficult to quantify statistically, and as such, financial support for local history projects can be difficult to obtain. Recently, a visitor from New Zealand (a former Government Minister) called into our offices for help with his family history. He might be described as a ‘genealogy tourist,’ someone who travels to a country of interest and uses footfall to seek information that might be difficult to obtain by other means. He is not alone – our records testify to that.

The Irish diaspora is far flung: people come from great distances to seek the land of their forefathers. A good example is Derrynane, ancestral home of The Liberator, which attracts great numbers of people easily enumerated on a balance sheet – 355,000 visitors in 2021 compared to just over 3,000 in the 1950s.[1]

The challenge facing small localised heritage projects, however, wherein visitors seek out an ancestral ruined castle, or a farm, or a house on a road where their forebears lived, is how to show such events without a formal record.

Arts for Wellbeing

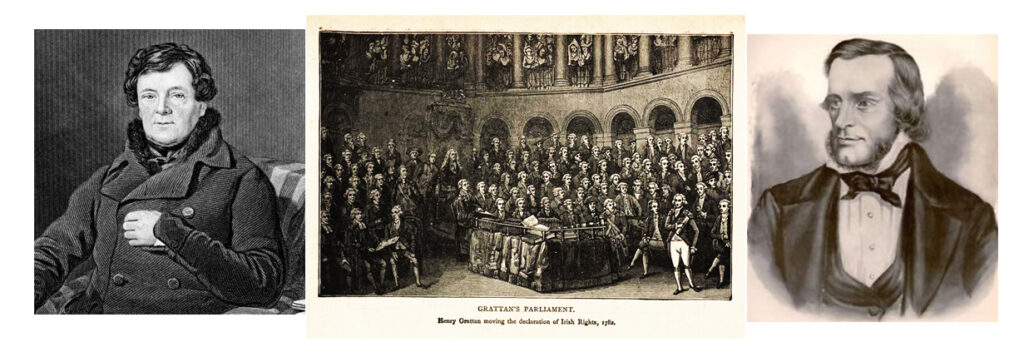

In 1845, Thomas Osborne Davis (‘The Celt’), co-founder of The Nation, addressed an audience in Dublin on the importance of history and art for the wellbeing of society.[2] His speech was delivered at the first banquet of ‘the ’82 Club’ held in the Pillar Room of the Rotunda on 16 April 1845. The Liberator presided, and over one hundred members of the club were dressed in national costume.[3]

It was said that O’Connell, on entering the hall with a group of friends in full costume, resembled more ‘a field-officer surrounded by his staff’ than ‘the leader of millions peacefully struggling for liberty.’[4] Behind O’Connell’s chair was placed a recently completed painting of the Declaration of Irish Independence on 16th April 1782 – the impetus for the club’s formation.[5] The artwork, which depicted Grattan and Irish statesmen in the Irish House of Commons,[6] was the work of an artist named Nicholas Kenny.[7]

Young Davis numbered among more than twenty speakers who addressed the audience.[8] He was among the last to rise, his subject the ‘close connection between national art and national independence.’ His speech, quite possibly his last, is given here in full:

Art is the born foe of slavery, and of the friends of slavery – of ignorance, sensuality, and cowardice. It is, therefore, your proper ally. It is no fantastic or speculative assertion that national art is closely connected with national independence; philosophy affirms it – history affirms it. Art has flourished under every variety of domestic government – under oligarchy, monarchy, and democracy – under Pope, Prince, and People – but it never flourished under a foreign rule. Its highest conceptions are denied to provinces, like progeny to the imprisoned eagle. Nor can smallness of size disable a country from greatness in art. Antwerp, Florence, Athens, each of these did far more for art than all the empires now existing on earth, but they were independent. It is not smallness of size but meanness of spirit that forbids high art. It is most natural it should be so. How can he who only sees in the faces of his fellows the cunning of struggling slavery – how can he whose gaze can rest on no native landscape that is not marred by painful and servile slavery, be a consummate artist? How can he who never heard the shout of free men, never looked on the ‘sight entrancing’ of citizens arranged in arms for freedom, how can he who rarely meets a face confident with patriot strength, or the form lifted by a great ambition – how can he reach the rank of a national artist? Yet Ireland is eminently fitted to compete with Europe in art. The organisation of our people is exquisitely subtle, and their minds romantic and believing. The aspect of the country is more variable and suggestive than any perhaps in the world, considering our circumstances. We have proved by example, too, that the mind and hand of the Irish are apt to devise and delineate. We sent out a Barry, whose abounding grandeur towered over the cleverness of England like a forest-tree among flowers – a Forde (whose name is too little known, and whom I cannot allude to without mourning) – that true son of the soil – that home-taught, untravelled, genuine native; yet whose imagination was distinct in its stormiest hours, and whose pencil was true as a sunbeam.[9] I am loathe to speak of living artists – of Maclise (who has just taken the highest prize and the highest honour of art from the whole empire), of Burton, and Hogan, and Danby, and Mulready – I need not enumerate them; I am incompetent to judge them; time will judge them. Yet they are but earnests of what Irish art would become if Ireland were independent. Art, I repeat, is your proper friend. It may make our country more familiar, and, with that familiarity, more dear to our countrymen; it may realise the spirit of our touching superstitions – it may picture the dignity that stalks in freize, and the heroic affections that circle round the peasant’s hearth. It can do much more. It controls not only the present, but the past and the possible.

Here Davis addressed O’Connell directly, linking the portrait placed behind the great man to his vision of independence:

If I may judge by the effect which that picture behind you, Sir, produced tonight, the service which art could give us by representing her history through Ireland’s eye to her heart would be enormous. It would put before us the horny hand and cruel aspect of the oppressor, it would picture the sufferings, the struggling wrath, the hot outbursts of the oppressed, it would seclude the slave, and shame him at his own baseness, hurry the doubting to the battle-field it pictured, and inflame the heart of the fearless patriot with a gladdening prophecy. You, Sir, are interested then in the advancement of art, and it is equally concerned for your success. I do not speak of the patronage which a restored aristocracy and an educated and ambitious people would give it. I speak of the spirit you will infuse into it. I speak not of the money, but the passions of independence. Make Ireland a nation, and you will do more for national art than if you mortgaged your estates for pictures, and turned your town halls into drawing schools. Make Ireland a nation, and the Irish artist will feel himself a partner in your toils, your ambition, and your renown; he will be nourished upon the great sights and thoughts of a liberated people – he will be surrounded by men vying in nationality, and worshipful of national genius; he will dedicate that genius to honour the influence that inspired it.

Davis drew his speech to a close by proposing a toast to the advancement of the Fine Arts in Ireland.

Over the following months, Davis at times differed in opinion to O’Connell, notably on the Irish Colleges Bill. At a Repeal meeting – in what was described as ‘a public rupture between Young Ireland and Old Ireland’ – a misunderstanding between the two men reduced both to tears. They subsequently shook hands warmly – and ‘as roughly as a pair of prizefighters previous to a contest.’[10]

Indeed, in a drama about the Liberator staged at the Gaiety Theatre Dublin one hundred years later, the then historic figure of Davis was among those portrayed.[11]

Thomas Davis died on 16 September 1845 aged 30. In Kerry, the news reached The Liberator in Derrynane from where, on 17th September, he wrote:

As I stand alone in the solitude of my mountains, many a tear shall I shed in memory of the noble youth. Oh! how vain are words or tears when such a national calamity afflicts the country … I can write no more – my tears blind me.[12]

Vita Brevis, Ars Longa[13]

This year (2023) marks the 180th anniversary of a lamentation written by Davis about the chieftain O’Sullivan, whose ship was wrecked in Bantry Bay and who drowned within sight of his castle at Dunboy. It is a small illustration of how historical events such as this (which probably dates to the sixteenth century) were, until relatively recent times, articulated in oral lore and passed down for centuries.

Davis provided the following background to the composition:

O’Sullivan’s Return is founded on an ill-remembered story of an Irish chief returning after long absence on the continent, and being wrecked and drowned close to his own castle. The scene is laid in Bantry Bay, which runs up into the county of Cork in a north-easterly direction. A few miles from its mouth, on your left hand as you go up, lies Bear [Bere] Island (about seven miles long), and between it and the mainland of Bear lies Bear Haven [Bearhaven/Berehaven], one of the finest harbours in the world. Dunboy Castle, near the present Castletown, was on the main, so as to command the south-western entrance to the Haven. Further up, along the same shore of Bear, is Adragool [Adrigole], a small gulf off Bantry Bay. The scene of the wreck is at the south-eastern shore of Bear Island. A ship, steering from Spain by Mizen Head for Dunboy, and caught by a southerly gale, if unable to round the point of Bear and to make the Haven, should leave herself room to run up the bay towards Adragool or some other shelter.[14]

Somewhere in the Annals of Ireland, no doubt, in the long history of the O’Sullivan clan, there is record of this event.

O’Sullivan’s Return

To the air of Cruiskeen Lawn – Slow time[15]

O’Sullivan has come

Within sight of his home,

He had left it long years ago;

The tears are in his eyes,

And he prays the wind to rise

As he looks tow’rds his castle from the prow, from the prow,

As he looks tow’rds his castle from the prow.

For the day had been calm,

And slow the good ship swam,

And the evening gun had been fir’d;

He knows the hearts beat wild

Of mother, wife, and child,

And of clans who to see him long desir’d, long desir’d,

And of clans who to see him long desir’d.

Of the tender ones the clasp –

Of the gallant ones the grasp –

He thinks until his tears fall warm;

And full seems his wide hall,

With friends from wall to wall,

Where their welcome shakes the banners, like a storm, like a storm,

Where their welcome shakes the banners, like a storm.

Then he sees another scene –

Norman churls on the green –

‘O’Sullivan aboo,’ is the cry;[16]

For filled is his ship’s hold

With arms and Spanish gold,

And he sees the snake-twin’d spear wave on high, wave on high,

And he sees the snake-twin’d spear wave on high.[17]

‘Finghin’s race shall be free’d[18]

From the Norman’s cruel breed –

My sires freed Bearra once before,

When the Barnwell’s were strewn

On the fields, like hay in June,

And but one of them escaped from our shore, from our shore,

And but one of them escaped from our shore.’[19]

And, warming in his dream,

He floats on victory’s stream,

Till Desmond – till all Erin is free.

Then, how calmly he’ll go down,

Full of years, and of renown,

To his grave near that castle by the sea, by the sea,

To his grave near that castle by the sea!

But the wind heard his word,

As though he were its lord,

And the ship is dash’d up the Bay.

Alas! for that proud barque,

The night has fallen dark,

’Tis too late to Adragool to bear away, bear away,

’Tis too late to Adragool to bear away.

Black and rough was the rock,

And terrible the shock,

As the good ship crashed asunder;

And bitter was the cry,

And the sea ran mountains high,

And the wind was as loud as the thunder, the thunder,

And the wind was as loud as the thunder.

There is woe in Bearra,

There is woe in Glengarrah,

And from Bantry unto Dunkerron.

All Desmond hears their grief,

And wails for their chief –

“Is it thus, is it thus that you return, you return –

Is it thus, is it thus that you return?”[20]

‘Don’t Throw out the Old Water’

Technology is rapidly changing the way we communicate the past in the manner of Davis. Octogenarian John Roche, Chairman of Castleisland District Heritage, was part of the oral tradition and wonders if we are communicating the richness of our past at all:

The expansion in modern technology only started in the middle of the last century after the end of World War II when the massive investment in ‘weapons of mass-destruction’ was switched to the advancement of technological inventions for peaceful trade between the masses. About that time a certain professor predicted that “in the future computers won’t weigh more than a tonne” – an example of the trickle of change in technology that turned into a raging torrent. People seem to have bought into all this change with scarcely a thought for what we are losing of the old world.

There was a saying in my youth, ‘don’t throw out the old water until you’re sure you have fresh water to bring in.’ By ignoring that principle, and embracing everything new as it became available, we have paid scant attention to the best of the Olde Worlde – such as the local lore that Castleisland District Heritage is trying to document and record for posterity.

We are working against the clock trying to tap the memories of the last generation reared before TV took over the young people’s mind set, and finished forever the generational passing on, and absorption of family and local lore. Every day sees the passing of octo- and nonagenarians, taking with them a bank of memories which will be interred with their bones, never again to surface – lost forever. Yet there is no political or financial support for the type of work needed to save the last vestige of local lore: as we were informed, “There’s no money in the Department of Education for local history!”

___________________

[1] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/daniel-oconnell-on-the-protestant-church-in-kerry/ [2] Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 19 April 1845. [3] Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 19 April 1845. The costume was described in detail, a coat in rich emerald green cloth of Irish manufacture of full-dress military style fashion, double-breasted, buttoned to the throat with standing collar in green velvet embroidered in gold with a stalk of shamrocks, the cuffs the same as the collar, with two rows of gilt buttons on the breast equi-distant from the central line; buttons inscribed ‘1782’ encircled by a wreath of shamrocks. At the back of the coat at the waist were two embroidered flaps in the same design as the collar and cuffs. Pantaloons in the same cloth as the coat with rich gold lace, one and a half inches wide, on the outer seam of each leg. A cap of green cloth with gold edging with a band of the same gold lace. [4] Ibid. [5] The object of the club was given thus (Weekly Freeman’s Journal, 19 April 1845): ‘On 16th April 1782 Grattan moved the declaration of Irish independence; on the corresponding day in 1845 the men of this brotherhood determined to pledge themselves to their country, and to each other, that they would never cease to struggle whilst Ireland was enthralled, and that the summit of their aspiration was the legislative independence of their native land.’ On the subject of O’Connell’s chair, a correspondent of Castleisland District Heritage shares the following: ‘My great grandmother came from a farm near Castle Gallagh outside Castleblakeney in Co. Galway. One of her matriarch’s was Mary Breen a cousin of Daniel O’Connell. My father’s cousin told me that as a child she can remember staying often at the farm where they still had “Daniel O’Connell’s Chair” so-named because he sat in it during a visit long ago.’ [6] The painting, ‘Declaration of Irish Rights in 1782,’ was completed in 1844 for Henry Grattan junior (A Dictionary of Irish Artists, 1913). It depicted Grattan and other celebrated Irish statesmen of the day on the floor of the Irish House of Commons in the military dress of the Volunteers, supported by Flood and other members of the national party. It was reproduced in the Graphic, 6 March 1886 by permission of C Langdale Esq and in ‘the extra Christmas number’ of Lady of the House magazine (1906) by permission of Major Langdale of Houghton Hall. [7] Little is known about Kenny but the following remark about his family is of interest: ‘The beautiful church of the Carmelites at Knocktopher, county Kilkenny, has undergone a perfect renovation under the guidance of Very Rev Abbe Scally and the great artistic skill of Mr Kenny, painter and decorator, of Thomastown, and brother to that distinguished portrait painter, the late Nicholas Kenny Esq of Dublin whose painting of the Irish House of Commons on the occasion of Grattan’s grand oration for Irish independence elicits the admiration of all’ (Carlow Morning Post, 10 September 1859). [8] Richard Albert Fitzgerald MP numbered among the speakers and paid tribute to Carolan, ‘Notwithstanding all the power and might of English kings and governments to destroy our nationality, we are Irish still. We have the same love for the arts and sciences our forefathers had. We have the same passion for music and every other art that can elevate the mind or purify the heart.’ [9] Cork artist Samuel Forde (1905-1828). Further reference, https://roaringwaterjournal.com/tag/fall-of-the-rebel-angels/ [10] An account of the encounter at a meeting of the Repeal Association on 26 May 1845 is given in the Northern Warder and General Advertiser, 5 June 1845. [11] The play, King Dan – ‘An Imaginative Play about Daniel O’Connell and his wife Mary’ by Aodh de Blacam (Blackham) was written in 1944 ‘with the atmosphere of Iveragh in it.’ The author said at the time, ‘Mary O’Connell was the real Liberator. I see her as the maker of the leader; his guide, his better genius. I have tried to remind our people of their debt to that noble lady’ (Kerryman, 28 October 1944). De Blacam described his difficulty in getting O’Connell to the stage: ‘O’Connell was not a man, he was a multitude. To get his vast movement on the stage, his monster meetings, his oratory, his pugnacity was a hard task … I half wished for the scope of a film as in Arliss’ fine picture of Disraeli’ (Interview with the playwright, Dublin Leader, 2 December 1944). The play was produced by Lord Longford and his wife Christine, Countess of Longford (Longford Productions), O’Connell portrayed by Hamlyn Benson and Mary O’Connell by Cathleen Delany. Costume design was by Carl Bonn. It was asked (and by some still is asked) why the Liberator had suffered so much neglect by dramatists, ‘the gigantic figure with large virtues and large faults, never yet has been seen in drama save in a stage version of Canon Sheehan’s Glenanaar’ (Irish Press, 4 December 1944). Unfortunately, the play was not well received by the critics though it was accepted as historically correct. ‘The author makes more of the character of Mary O’Connell than the famous liberator’ was one complaint (The Stage, 14 December 1944). The play was removed after a week. ‘Blacam said the critics were wrong and that he was right … Might it not be that the audience were unused to such subject matter’ (Nenagh Guardian, 24 February 1945). Daniel O'Connell; or, Kerry's Pride and Munster's Glory, a play about the life of Daniel O'Connell was written and produced in 1880 by John C Levey (1838-1891). It was staged at the Alexandra Theatre, Sheffield; Pullan's Theatre, Bradford and Theatre Royal, Hanley in July and August 1880. A synopsis of the play (which seems to be lost), is held in the archives of CDH. [12] The letter in full, addressed to Thomas Matthew Ray, appears in The Correspondence of Daniel O’Connell Vol II (1888): ‘My dear Ray,—I do not know what to write. My mind is bewildered and my heart afflicted. The loss of my beloved friend, my noble-minded friend, is a source of the deepest sorrow to my mind. What a blow—what a cruel blow to the cause of Irish nationality! He was a creature of transcendent qualities of mind and heart; his learning was universal, his knowledge was as minute as it was general. And then he was a being of such incessant energy and continuous exertion. I, of course, in the few years—if years they be—still left to me, cannot expect to look upon his like again, or to see the place he has left vacant adequately filled up; and I solemnly declare that I never knew any man who could be so useful to Ireland in the present stage of her struggles. His loss is indeed irreparable. What an example he was to the Protestant youths of Ireland! What a noble emulation of his virtues ought to be excited in the Catholic young men of Ireland! And his heart, too! it was as gentle, as kind, as loving as a woman’s. Yes, it was as tenderly kind as his judgment was comprehensive and his genius magnificent. We shall long deplore his loss. As I stand alone in the solitude of my mountains, many a tear shall I shed in the memory of the noble youth. Oh! how vain are words or tears when such a national calamity afflicts the country. Put me down among the foremost contributors to whatever monument or tribute to his memory shall be voted by the National Association. Never did they perform a more imperative, or, alas! so sad a duty. I can write no more. Fungar inani munere.’ The occasion is also recorded in The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps) (1861) by John Mitchel. [13] ‘Life is Short, Art is Long.’ Aphorism can be seen on the Abbeyfeale Heritage Trail (No 9) at Lower Main Street, the former premises of W D O’Connor. The architectural art is by Pat McAuliffe (1846-1921) of Listowel, Co Kerry, roofer, plasterer, and self-taught Stucco Artist. A short film about him by Abbeyfeale Community Council can be viewed here (https://www.facebook.com/abbeyfealecommunitycouncil/). [14] Nation, 8 April 1843. The verse was also published in The Spirit of the Nation produced by the writers of the Nation newspaper and in The Poems of Thomas Davis (1846) edited by Thomas Wallis. The latter includes another verse, ‘The Fate of the O’Sullivans’ in which Davis writes: ‘After the taking of Dunbwy and the ruin of the O’Sullivan’s country, the chief marched right through Muskerry and Ormond, hotly pursued. He crossed the Shannon in carachs made of his horses’ skins. He then defeated the English forces and slew their commander, Manby [sic], and finally fought his way into O’Ruare’s country. During his absence his lady (Beantighearna) and infant were supported in the mountains, by one of his clansmen, M’Swiney, who, tradition says, used to rob the eagles’ nests of their prey for his charge. O’Sullivan was excepted from James the First’s amnesty on account of his persevering resistance. He went to Spain, and was appointed governor of Corunna and Viscount Berehaven. His march from Glengariffe to Leitrim is, perhaps, the most romantic and gallant achievement of his age,’ A correspondent of CDH suggests that ‘Manby’ may be Sir Nicholas Malby (https://www.dib.ie/biography/malby-sir-nicholas-a5408). Of the clan O’Rourke (O’Ruare/Ruairc), he writes, ‘Brian sheltered Francisco de Cuéllar and other Armada survivors and eventually paid for it with his life. As a boy I can remember asking my grandmother a typical childish question, “Grandma, why do we have brown hair?” I can still see her pause a moment while looking out the window before answering …“The Spanish”.’ [15] The slow time of the Cruiskeen Lawn is what the Scotch, with little alteration, play as ‘John Anderson my joe!’ An cruisgin Ián is the spelling in The Poems of Thomas Davis (1846). [16] Given as ‘O’Suilleabháin abù’ in The Poems of Thomas Davis (1846) by Thomas Wallis, p105. [17] The Standard bearings of O’Sullivan (Nation, 8 April 1843). [18] See O’Donovan’s edition of the Banquet of Donna U-Gedh and the Battle of Mag Rath for the Archaeological Society, App, p349, ‘Bearings of O’Sullivan at the Battle of Caisglina.’ I see, mightily advancing on the plain,/The banner of the race of noble Finghin;/His sear/spear with a venomous adder (entwined),/His host all fiery champions. Finghin was one of their most famous progenitors. The name O’Sullivan signifies the children of the one-eyed. The name originated with Ruchaidh, chief of Bearra. He was blind of one eye. He had never been known to refuse a request. To test this boundless generosity, his favourite bard asked him to give him his remaining eye, and, as the story goes, he plucked it out. A caoine for Daniel O’Sullivan of Dunlough, the son of Owen Ruadh, who died in 1764, and was buried in the Abbey of Fiorthial, has this couplet: Though darkness to him, it was fame to his line,/Who gave his last eye as a proverb to shine. This, says a biographer, is, no doubt, the proverb preserved in Mr Crofton Croker’s Fairy Legends. Nulla manus tain liberalis atque generalis atque universalis quam Sullivanis? (Nation, 8 April 1843). [19] The Barnwells were a Breton family, who came to England with William the Norman, and in Henry the Second’s reign ‘won great possessions at Bear Haven’ but were all slain, save one, by the O’Sullivans. Whether the ‘one’ was a young man, or a woman with child, has been differently stated (see Lodge’s Peerage and Stainhurst). Certain ‘tis, this one founded the great family of Barnwell, afterwards Lord Trimleston, Kingsland, &c in Fingal (see D’Alton’s County Dublin, 302, &c) (Nation, 8 April 1843). [20] The verse is given thus in The Poems of Thomas Davis (1846) by Thomas Wallis: ‘There’s woe in Beara,/There’s woe in Gleann-garbh,/And from Beanntraighe unto Dun-kiarain;/All Desmond hears their grief,/And wails above their chief –/”Is it thus, is it thus, that you return, you return –/Is it thus, is it thus, that you return?”