On the nerve of this telegraph wire Be – Nothing of science, or profit and loss; But, flashing electrical deeper and higher, World, let the first heart-stirring message across – Be ‘Glory to God in the Highest!’ From The First Message for the Atlantic Telegraph Written at Albury, Guildford, 27 July 1857 by Martin Farquhar Tupper (1810-1889)1

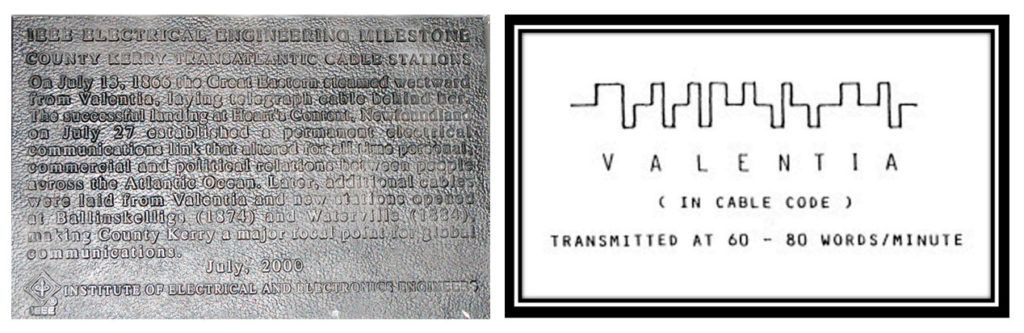

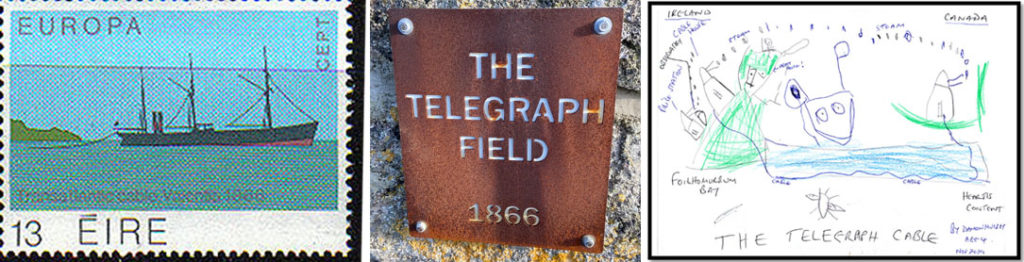

In the year 1866, the door was opened to telegraphic communication between Europe and America when the first fully successful cable link was made between the Telegraph Field at Foilhomurrum, Valentia Island, Co Kerry and Heart’s Content, Newfoundland.

Since 2003, the Telegraph Field, a site of outstanding historical importance, has been in the ownership of the Browne family. In that year, Junior Browne of Main Street, Castleisland, purchased the Telegraph Field with the intention of building a holiday home.3

However, when Junior learned of the history associated with the field, he decided against building, and instead, set about preserving its history by making a short film about it.4

The quiet desolation of the Telegraph Field today, now owned by Junior’s son, Peter, belies jubilant scenes there on 27 July 1866 when the cable connection was made.5 The ruined cable station is a solitary and melancholy reminder of the feat accomplished by teams of dedicated professionals from around the world, working together for the benefit of a connected future.

That pivotal moment, and the efforts made in the preceding years of 1857, 1858 and 1865, captured the imagination of artists and writers who with great skill placed their interpretations of the phenomenal event on record.

Connection: Foilhomurrum, Coarha Beg, Ireland, to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, Canada

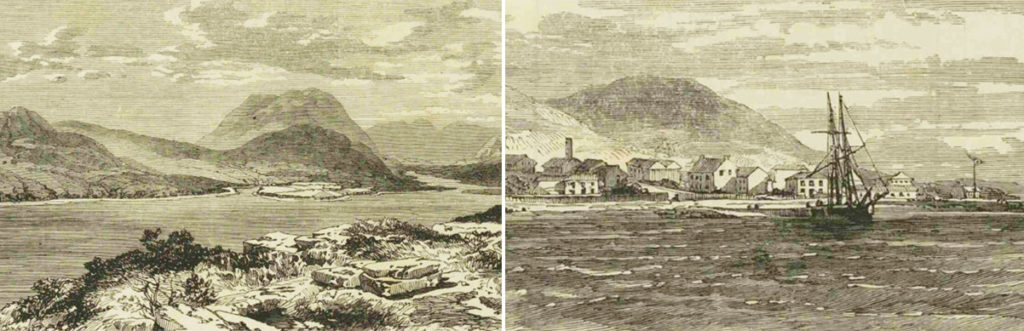

In 1865, Foilhomurrum was described as follows:

At the extreme end of the island of Valencia is a rocky creek or small arm of the sea called Foilhummerum, bounded on one side by the mainland and adjacent islands and on the other by a huge headland, in comparison with which Howth dwindles into insignificance. This creek is sheltered from the Atlantic waves which everlastingly break against the outer cliffs in foaming masses which can be seen at a distance of miles and it is the point which has been selected for the Irish shore end of the cable.6

The extent of the operation was also described:

The ocean to be spanned from the coast of Ireland to Newfoundland is sixteen hundred and forty miles. For this purpose it was necessary to have two thousand four hundred miles of cable in order to provide for any deflections from the direct course in laying it. The weight of the present cable is 35cwt to the miles, nearly double that of the former one which was only 19cwt to the mile … The shore end is much stronger and heavier in order to be capable of resisting the action of the sea and of the bottom in shallow water and weighs eighteen tons to the mile.7

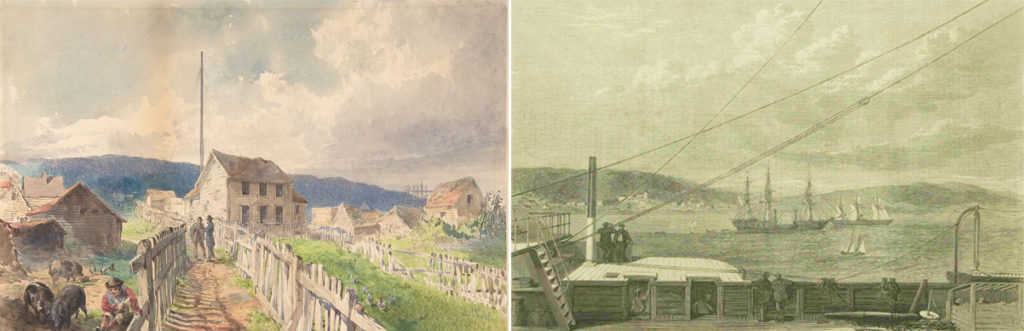

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the same year (1865) came a description of Heart’s Content:

In the first place, there are no buildings of note; in the second place, there are no people of any consequence. Nothing in or of itself suggested its name nor secured its present prominence. The bay has done all that will hereafter make the name of the place famous. There may be a thousand people at Heart’s Content if one should count all the men, women, very small children and strangers but we should say that 700 was a more rational number. These people fish for a living and eat fish for sustenance. At the present time their chief source of amusement and profit is the great number of strangers who are accidentally thrown among them.8

The surrounding area of Trinity Bay, however, ‘some 30 miles from the former cable terminus,’ was more impressionable:

For the purposes of commerce it is and can be of no avail for there are no avenues of trade here; but for the landing place of the cable for the safe anchorage of great ships of war … the bay is simply superb. Should success attend the present enterprise – should the laid cable be enabled to do its duty – this place will become one of the curiosities of the hemisphere. It cannot fail to grow and become a great resort.9

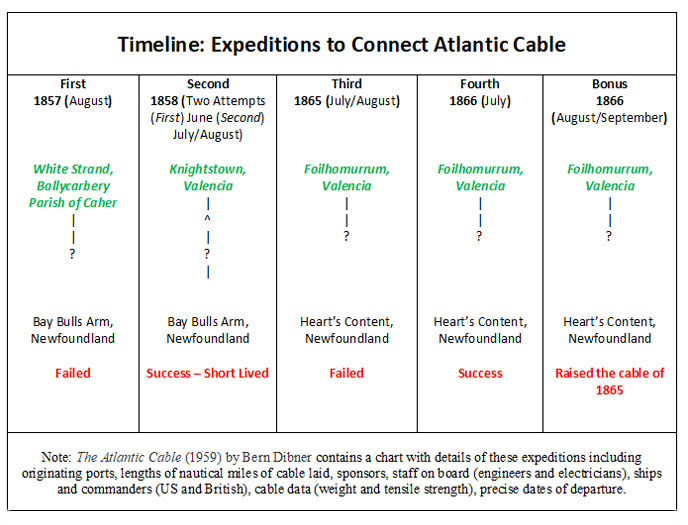

The Expeditions

Much has been written of the four expeditions to lay the telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in the years 1857, 1858, 1865 and 1866.10

A picture, however, paints a thousand words, and it was through the eyes of the artist that the events were most majestically captured.

1857: First Expedition

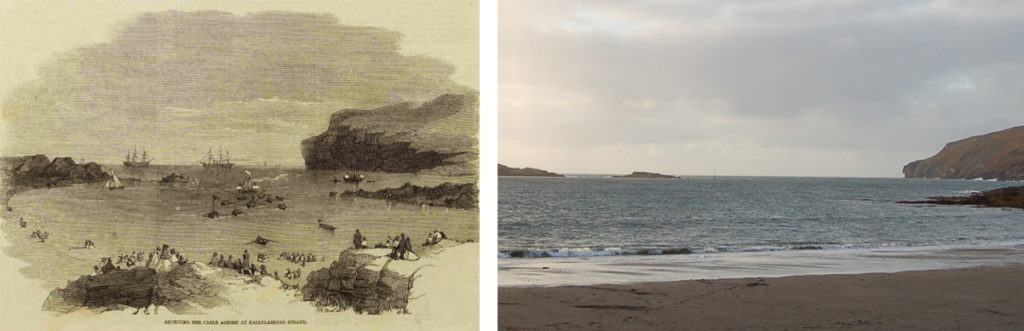

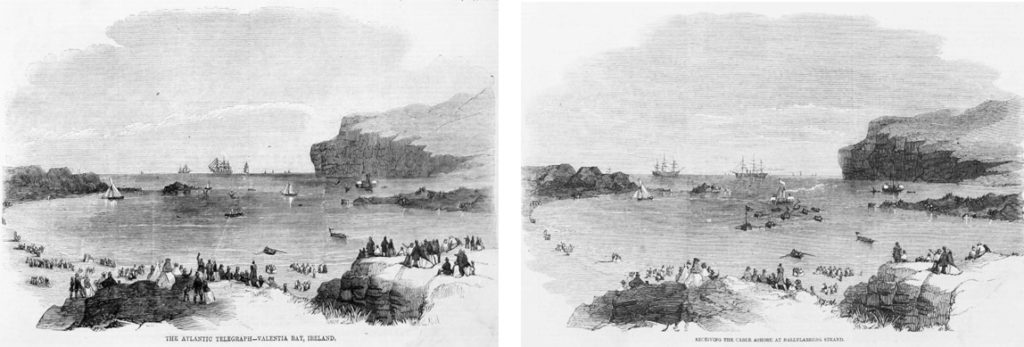

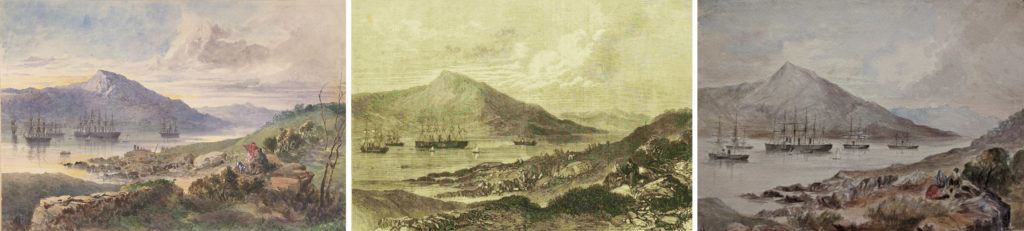

Artist Edward William Cooke left a number of illustrations of the first attempt to lay the Atlantic telegraph cable.

In 1857, a local Kerry newspaper reported that Mr Cooke was ‘about to paint a grand picture in celebration of the sailing of the Atlantic telegraph squadron.’ The reporter added that Mr Cooke ‘was at Valentia making sketches of the very lovely scenery which abounds in that neighbourhood with a view to entire accuracy in the local details of his work.’11

An anonymous ‘special artist’ for the Illustrated London News, however, for which Cooke cannot be ruled out, also put his artistic skills to good use.12

Summary of Expedition:

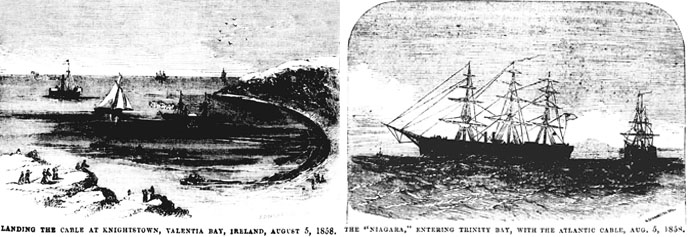

Connection was made in a temporary telegraph house on the beach at Knightstown, via White Strand, near Caherciveen, the point of departure fixed at ‘Begnis, the property of John Leahy Esq’ on the mainland.13

There was much celebration in Knightstown. Two hundred guests were invited to dine in an improvised Banquet Hall there – the ground floor of the store attached to the slate factory. Under the direction of John Lecky, the store was transformed with material from the factory to create an entrance at an elevation of ten feet, with a monster slab about 15 feet long and broad on which was painted, ‘Success to the Cable’:

A 70ft passage was laid with Valentia slab and covered at either side with arched white calico, festooned with laurels, evergreens and flowers. The walls of the hall were covered and decked with laurel, palm and fuchsia. The ceiling was ‘hid from the eye’ by a grove of laurels and candelabra worked out of evergreens and encircled with pink calico. At the head of the room was a scroll, Cead mille failtha. There was also a scroll, over which floated the Union Jack, with the letters ‘V.R.’ cipher of her Majesty, and another, below the Stars and Stripes, ‘J.B.’ the cipher of John Buchanan, President of the United States.14

Addresses were given (and returned) by the Knight of Kerry, who gave especial thanks to Mr Brookly, and who replied on behalf of his brother directors, Messrs Field, Brown and Gurney; Lord Carlisle; the Lord Lieutenant, guest of the Knight of Kerry; Dr Palmer of the Niagara; Very Rev Arthur Irwin, Dean of Ardfert; Right Rev Dr Moriarty; General Stokes, for the army; Captain Chads, RN, for the navy; James O’Connell, Sir William O’Shaughnessy, Edward Hussey, High Sheriff, and Dr Grey of the Freeman.

In the evening, there was a bonfire, fireworks, and all night dancing with music by the band of the Kerry Regiment. The following day, the cable was brought ashore:

The boats having come in very slowly, it was near seven o’clock when the end of the cable came on shore, his Excellency and Mr Cyrus Field pulling it together, as the representatives of the two countries. At this moment, and for an hour previous, the scene was very exciting and indeed beautiful; numbers of boats and yachts dotted the little bay, adding to the beauty of the islands and majestic headlands … the cable was brought on shore amidst loud cheers by the sailors of the squadron, assisted by the peasantry who were present in crowds.15

Among those present for the ceremonials, as well as ‘a large sprinkling of ladies,’ were the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Dunraven, Lord Rossborough, Hon Col de Moleyns, the Knight of Kerry, Sir Wm Godfrey, Sir Wm O’Shaughnessy, Messrs Talbot Crosbie, Conway Hickson, James O’Connell, Cronin Coltsmann, Shine Lawlor; Mr Cyrus Field, and the American gentlemen connected with the undertaking, Sir Edward McDonnell, Chairman of the Great Southern and Western.

The cable was deposited in a sunken channel made from the sea to the tent where the batteries were fixed and made fast … one of the American officers expressed a trust that they would be able to announce the consummation of the marriage between the two worlds in twenty days. Rev John G Day, Rector of Dromtarriff, then read a very chaste form of prayer specially drawn up for the event.16

The Agamemnon and Niagara divided the work. They set out from Kerry for Bay Bulls Arm, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, on 7 August 1857. On 11 August, the cable snapped, and the expedition was abandoned.

1858: Second Expedition

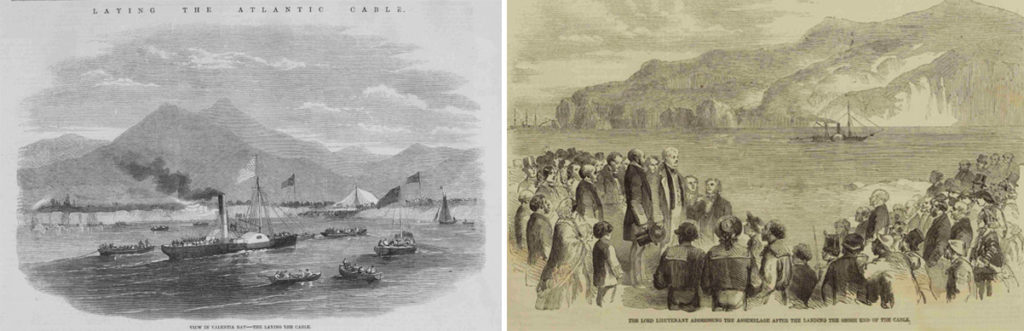

Artist William Simpson (1823-1899) captured the scene in Valencia during the second expedition to lay the telegraph cable.

Simpson, who was special artist for the Illustrated London News from 1866, distinguished himself as a war artist.

The special artists for other newspapers and periodicals also bequeathed their unsigned works of art. It was claimed that the laying of the Atlantic telegraph was more elaborately illustrated in Harper’s Weekly ‘than in all the other newspapers in the world.’17

Summary of Expedition

Those who crave detail will find that there were two attempts made during this expedition, in June and July. The cable, which had been in storage, was laid in a different manner during this attempt. Rather than laying it from one end to the other, two steamers met in mid ocean and sailed in opposite directions to their destinations, Bay Bulls Arm, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland and Knightstown, Valencia, Ireland.

In June, multiple breaks caused the project to be temporarily abandoned but the following month, they met with success, the two ships arriving at Valencia and Newfoundland on the same day.18

Knightstown was selected as the terminus:

Partly by the desire of the Knight of Kerry, and partly owing to the local importance of the place, it was decided ultimately that Knightstown was to be the main station. Communication was, however, temporarily established by the main cable being laid by boats from the Agamemnon to the newly selected terminus. A branch cable (shore end type) was then laid across the harbour, between Ballycarberry and Knightstown. A few days later this was under-run out to the buoyed shore end from Ballycarberry of the year before, where it was cut, and a splice effected between the seaward side and the heavy shore end.19

The cable end was landed at Knightstown where ‘Mr Bright, Professor Thomson and the other greatly tried members of the expedition’ were heartily welcomed by Peter Fitzgerald, the Knight of Kerry. It was at once taken into the cable-rooms by Mr Whitehouse, the electrician, and attached to a galvanometer, when the first message was received through the entire length.

On 16 August 1858, Queen Victoria in London sent the following message to James Buchanan, President of United States in Washington, which occupied 67 minutes in transmission:

The Queen desires to congratulate the President on the successful completion of this great international work, in which the Queen has taken the deepest interest. The Queen is convinced that the President will join with her in fervently hoping that the electric cable which now connects Great Britain with the United States will prove an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded upon their common interest and reciprocal esteem. The Queen has much pleasure in communicating with the President, and renewing to him her wishes for the prosperity of the United States.

The following reply was sent to Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of Great Britain:

The President cordially reciprocates the congratulations of Her Majesty the Queen on the success of the great international enterprise accomplished by the science, skill and indomitable energy of the two countries. It is a triumph more glorious because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilisation, liberty, and law throughout the world. In this view will not all nations of Christendom spontaneously unite in the declaration that it shall be for ever neutral, and that its communications shall be held sacred in passing to their places of destination, even in the midst of hostilities?

However, the cable speedily failed. It gradually weakened, and ceased on 1st September 1858 after having conveyed 129 messages from England to America and 271 messages from America to England.20 The cause was ultimately determined as cable related injuries and issues.21

The last word transmitted from Valencia to America was ‘forward’ – a word of good omen. It was sent to Cyrus W Field in New York:

Please inform American Government we are now in a position to do our best to forward – 22

‘The failure of the Atlantic Telegraph’ reported the contemporary press, ‘is now almost the only topic that people have to talk about.’23 The talk and the recouping of losses would continue for some years.

1865: Third Expedition

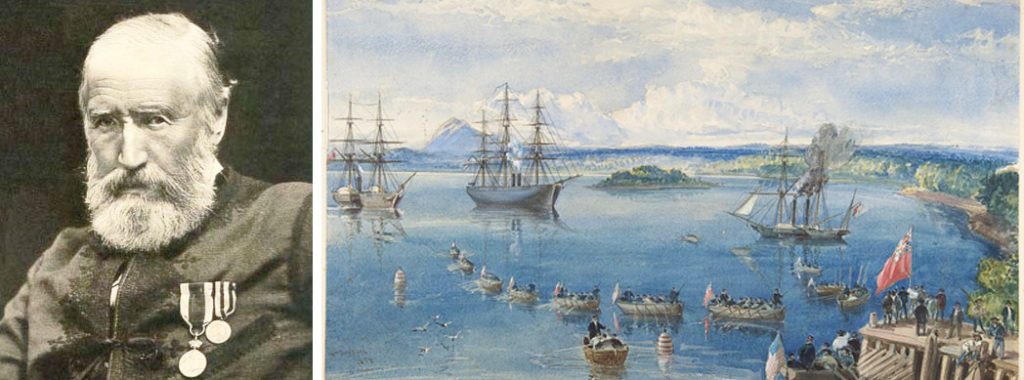

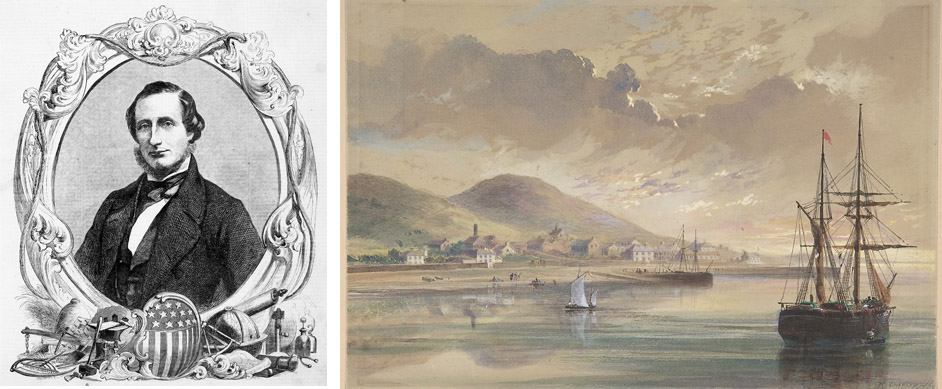

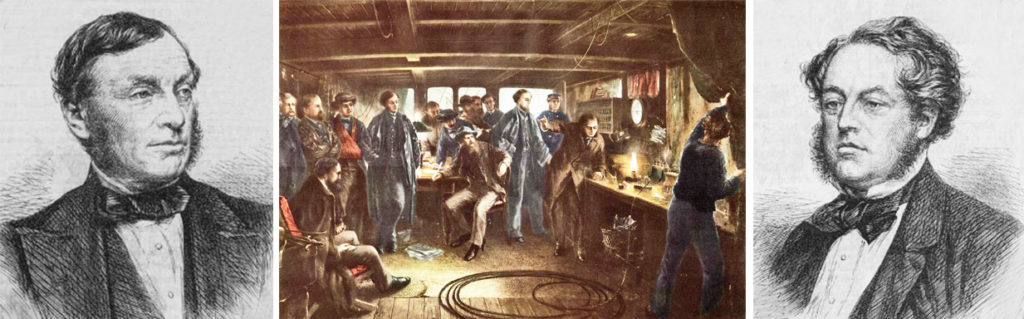

Artist Robert Charles Dudley (1826-1909) is the best known of the artists to capture the scenes of the expedition of 1865 – and 1866. Ironically, no image of Dudley appears to have emerged.24

Summary of Expedition

A new terminus at Heart’s Content, Trinity Bay, in Newfoundland, was selected for the next expedition. In 1865, Cyrus W Field visited Valencia Island ‘with the view of selecting the best point of departure for the Atlantic cable’ in Ireland:

After a very careful survey and examination of the line of coast, the committee selected Foilhamarrum Bay, under Bray head, at the extreme western end of Valentia Island.25

With the selection of the Telegraph Field at Foilhomurrum, it was envisaged that the area would become a town:

The selection of Foilhamurrum enables the Atlantic Telegraph Company to save several miles of costly line gives greater security to the shore end of the cable and will shorten somewhat the time required for the transmission of the electric current through the ocean. At Valentia a capacious telegraph station will be erected, furnished with all the latest inventions of telegraphic advance. Clerks, officers, boatmen, will be stationed here, and Foilhamurrum will become a market and town.26

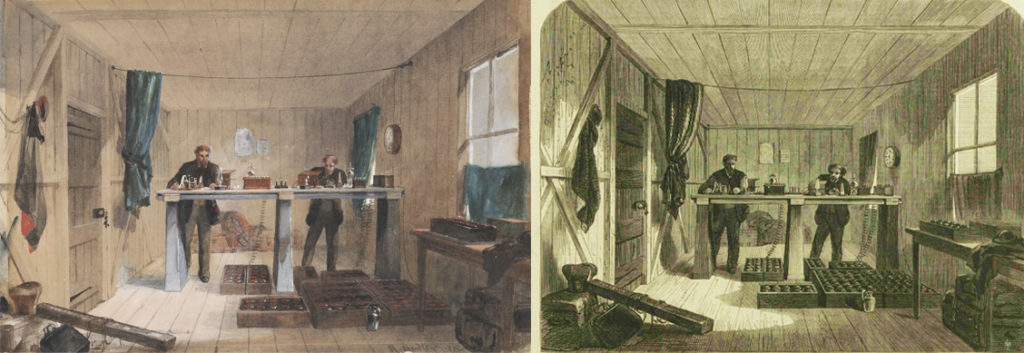

A temporary wooden telegraph-house ‘full of apparatus of various kinds for testing the cable in connection with the land-wires’ was soon erected in the Telegraph Field and a trench dug along the beach and up the cliff face to lay the thick shore end of the cable:

What the peasantry in the neighbourhood thought of the scene not even they themselves could say; they seem to have had a sort of vague idea that the cable was to carry them over to America, whither so many of their countrymen had emigrated.27

On 22 July 1865,the shore end of the cable was hauled out from the Caroline in Foilhomurrum Bay. The area was thronged with people, and ‘pocket handkerchiefs’ were seen waving from the tops of Foilhomurrum cliffs:

In Foilhommurrum Bay there assembled between three and four hundred men, picked from the finest peasantry in Europe, and capable of Herculean labours …Early in the morning, although the clouds lowered on the horizon, and the mists sailed densely over the mountain tops, and even kissed the higher cliffs, the sea was calm and the wind very light, so the Caroline was backed into the bay and anchored so that her stern was about three hundred yards from the shore … From right under her stern to the very shore there stretched two-and-twenty boats, from the smart cutter of the Great Eastern and the trim gig of the Coast-guard to the ordinary coast boat … Here and there, from the stern, floated a bit of bunting; but for bunting, real or imitation, the place to look was the top of the cliff on the right. All the pocket handkerchiefs, and a good many of the brighter shawls of the countryside, had been pressed into service for the occasion.28

The cable was hauled ashore by ‘enthusiastic Kerry men more given to shouting and cheering than to hauling’ and laid in the trench and hauled up the cliff ‘where enough had been laid in another trench dug from the face of the cliff to the telegraph operating house’:

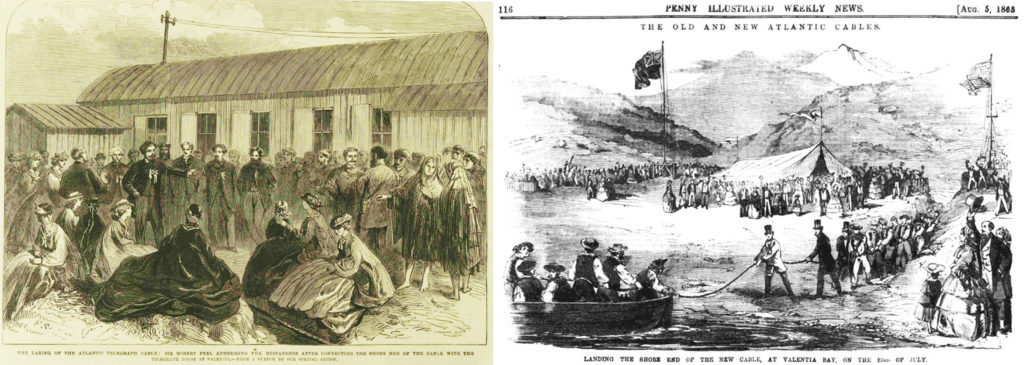

Here, in the presence of Sir Robert Peel, Lord John Hay, the Knight of Kerry, and a number of other more or less distinguished persons, the central wires of the thick shore end were connected with the speaking instrument, and a signal sent to and received from the Caroline. This difficult operation was, therefore, a success. Then, when this step in the communication had been secured, the Knight of Kerry, who has all along taken the greatest interest in the work, addressed to the throng a few words, expressing his satisfaction at the auspicious commencement of laying the cable. He called for three cheers for Sir Robert Peel and three more for the Atlantic cable.

Sir Robert Peel then spoke of the political, social, and commercial benefits of the project if successful and ‘after invoking the aid of Divine Providence,’ called for three cheers for the Queen, three for Mr Glass, and three for the President of the United States.

The Doxology was then sung, and Mr Glass formally announced the success of the test that had just been applied from the Caroline through 27 miles of shore end, ‘Cable all correct here; will you test.’29

The men returned to the beach and filled up the trench in which the cable lay. Soon after twelve, the Hawk arrived from Knightstown, and towed the Caroline out of the bay to lay the cable which was done at about two and a half miles per hour.

The next day, 23 July 1865, the shore end cable was spliced with the main cable on board the Caroline and the Great Eastern went forth on her journey across the Atlantic.

There was great anticipation of success in this year for much had been learned from the two earlier attempts. However, disaster was not far away, and on 2 August, the cable snapped. The Great Eastern reached Ireland with her mournful message on 17 August 1865.30

1866: Fourth Expedition

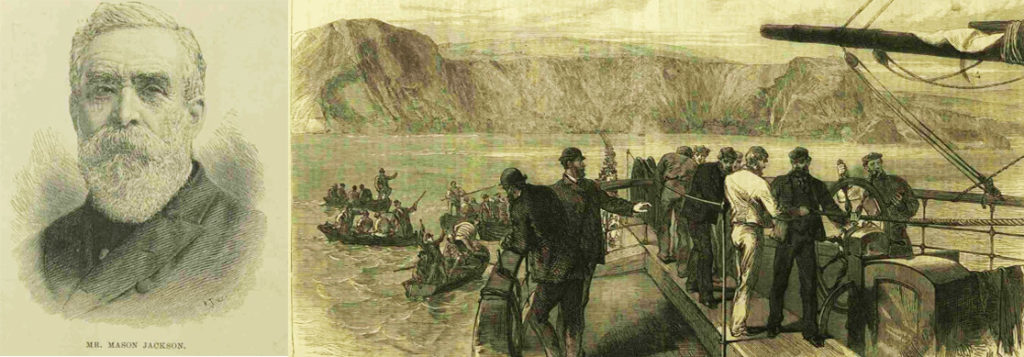

Artist Mason Jackson (1819-1903), author of The Pictorial Press: its Origin and Progress (1885) was Art Editor of the Illustrated London News at the time of the 1866 expedition.31 His distinctive symbolised signature (M struck through with a J), appeared on a number of illustrations from the successful expedition.

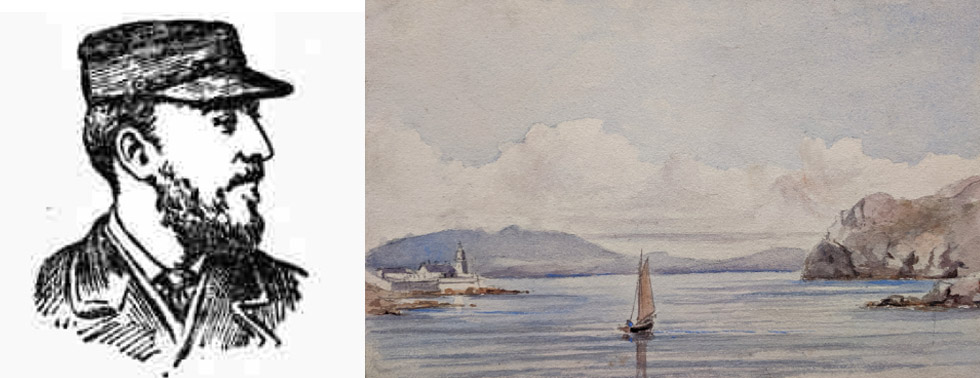

Lieutenant William Henn (1847-1894), Royal Navy, a celebrated yachtsman and owner of the yacht Galatea, also left a number of illustrations of the expedition.32

Summary of Expedition

With all the lessons learned from the former years, another expedition was carried out in the summer of 1866.33 People travelled to the Telegraph Field at Foilhomurrum, curious to see events there:

Many parties of tourists have arrived here, in the hope of seeing something of the operations connected with this great undertaking and the Telegraph-house on the cliffs of Foilhommerhum is daily beset by visitors, who use every interest to obtain admission. Its doors, however, are inexorably closed to all save the officials connected with working the line and the representatives of the London press.34

However, it was an altogether more subdued affair than that of 1865, as observed in the local press:

The people of Valencia and of the country around have been taken entirely unawares in the quick and quiet way the shore end cable of this year has been disembarked and embedded in its resting place at Foilhamurum. Last year throngs of people composed of all the classes, some coming from a great distance, attended for days at Valencia, in the hope of seeing the Great Eastern, and the more novel spectacle of laying the cable … but the numbers in each case this year have grown beautifully less, as indeed none at all can calculate on seeing the big ship off Valencia.35

On a grassy bank 50 feet down the cliff of Foilhomurrum, and as many feet from the water line upward, a lone lady artist, almost in imitation of Dudley, was observed seated with pencil gazing on ‘nature’s sublimest grandeur.’36

Meanwhile, the expedition underway, the Great Eastern was preparing to enter Bantry Bay in Cork, south of Valencia, having left the Nore in England on 1st July.

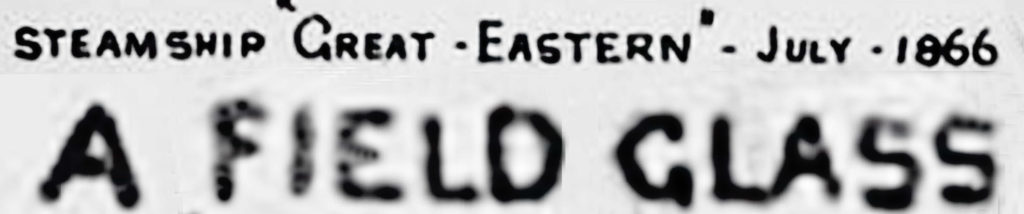

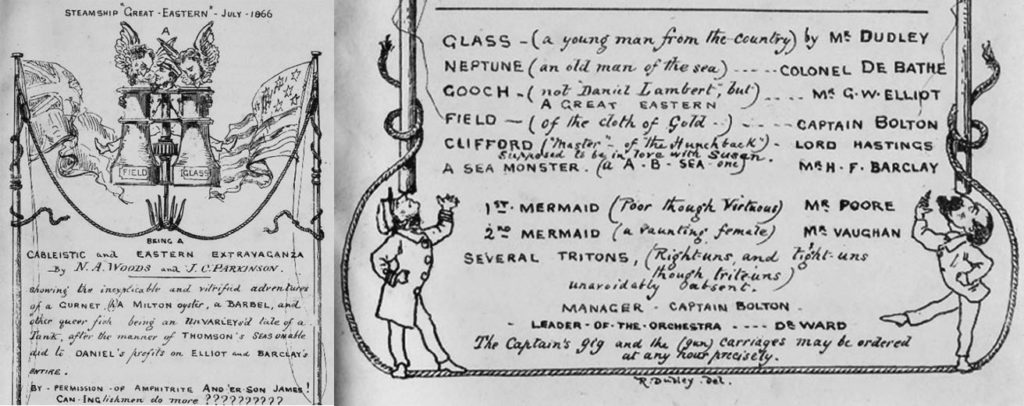

On board ship, Captain Frank Bolton, otherwise Sir Francis John Bolton (1830-1887), proposed that a play be produced to entertain those on board.37 Nicholas Augustus Woods of the Times and Joseph Charles Parkinson of the Daily News undertook to write it and with the aid of Colonel De Bathe of the Fusilier Guards, ‘a well-known amateur,’ A Field Glass; being a Cableistic and Eastern Extravaganza entered our literature, lithographed on board by Dudley.38

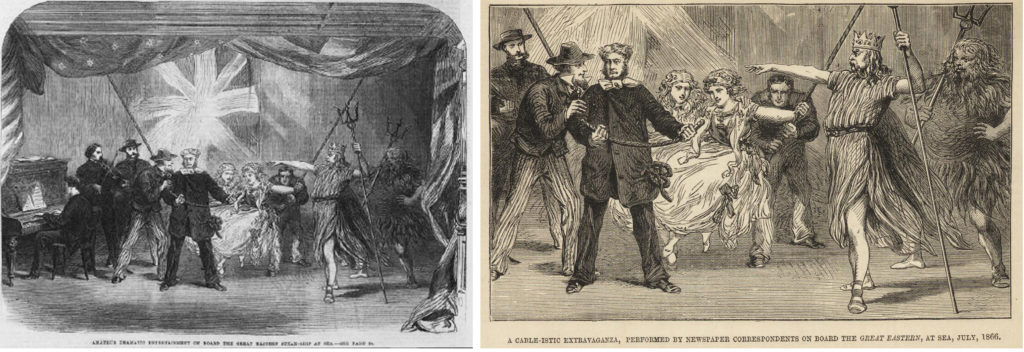

The saloon was rigged up as a theatre, the Union Jack and American flags were used as curtains. As for the costumes, ‘Where and how the dresses, especially those of the mermaids, were got on board the ship nobody perhaps but one of the ladies’-maids and one of the signalmen can tell.’ Passengers were treated to two performances.

The burlesque, built around Neptune’s wrath at the cables being laid in his ocean, was based on the principal characters engaged in the expedition.39

Robert Charles Dudley appeared in the performance as Mr Richard Atwood Glass (1820-1873), manufacturer of the cable. It may be a rare if not unique image of Dudley that occupies the forefront of the illustrations below.

As the serious work resumed, the directors of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company hosted a well-attended dinner at Valencia in a building adjacent to the hotel, specially fitted up for the occasion. It was followed by a religious service.41

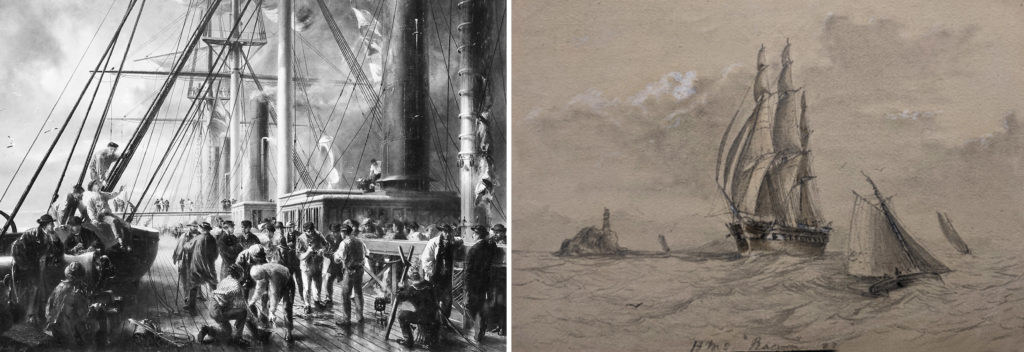

The following day, Friday the 13th July, the expedition commenced in earnest; the shore end cable was spliced to the main cable on board Her Majesty’s ship Racoon, witnessed by, among others, the Knight of Kerry. ‘At half-past three the Great Eastern shaped her course across the Atlantic, paying out the cable as she went along.’

All proceeded well, though a message on July 15 reported that a seaman had fallen overboard the Terrible, but was picked up and his life saved.

In Valencia, celebrations were being organised ahead of the connection:

In anticipation of its completion a great fete is preparing here for all the country people between this and even as far as Killarney … on the hospitable invitation offered to all around. The Knight of Kerry and Mr Glass are to be the entertainers. Fireworks and illuminations have arrived from Dublin and everything seems to promise a grand gala day and night to commemorate the successful laying of the Atlantic cable in 1866.42

Finally, on 27 July 1866, a successful connection between the two continents was achieved.

Messages were exchanged between Mr Daniel Gooch (1816-1889) at Heart’s Content and Mr Glass at Valencia.43

Once again, Queen Victoria sent a message, this time to Andrew Johnson, President of the United States. Both message and reply were shorter than those sent in 1858:

The Queen congratulates the President on the successful completion of an undertaking which, she hopes, may serve an additional bond of union between the United States and England.44

The president replied:

To Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland – The President of the United States acknowledges with profound gratification the receipt of Her Majesty’s despatch, and cordially reciprocates her hope that the cable that now unites the Eastern and Western hemispheres may serve to strengthen and perpetuate peace and amity between the Government of England and the Republic of the United States.

Meanwhile, at the Telegraph Field, Valencia, it was remarked that Mr Glass now ‘seldom leaves the telegraph house at Foilhomurrum, either night or day.’45

1866: ‘It is there!’

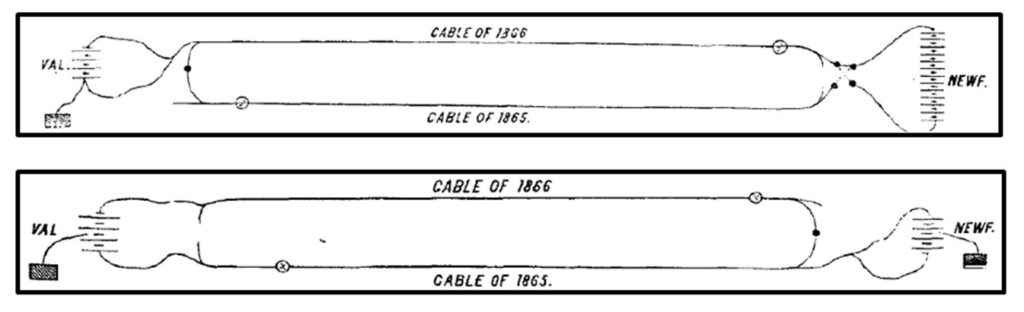

After the success in linking the two continents, an attempt was made in 1866 to retrieve the lost cable of 1865.

On 24 July 1866, a report from Foilhomurrum Bay indicated that the intended work would start almost immediately:

As soon as the Great Eastern has completed her work, that vessel, with the Terrible, Albany, and Medway, will at once and with all speed, working night and day, proceed to fill up with fuel. The Terrible and Albany will be coaled first, and start directly afterwards for the exact latitude and longitude in which the cable of last year was broken. When the precise spot is ascertained ‘marked buoys’ with which both ships are provided will be moored for guidance in grappling.47

Artist Neville Edye Sotheby Pitcher (1889-1959) left an interpretation of the scene.48

After much tense excitement, the 1865 cable was retrieved on 1 September 1866. Robert Charles Dudley described the moment:

For nearly three weeks – from August 12 when we reached the grappling-ground in mid-Atlantic, until Sept 1 – had hope and disappointment alternated in the hearts of those who, hovering like the falcon above the quarry, watched and waited to secure the prize that lay 4000 fathoms deep below. The claws of grapnel after grapnel had felt along the dark bed of the ocean in search to grasp the truant rope …the interest was breathless, one’s heart seemed in one’s mouth; scarcely a sound was heard from the entranced watchers … and as the grapnel, holding a vicelike grasp on the lost treasure, emerged still more slowly from the long-rolling waters, it was in almost whispered eagerness that the words passed from mouth to mouth, ‘It is there! It is there!’49

_____________

1 The first lines of the poem run as follows: (Strophe to Antistrophe) Poor World! that in wickedness liest/Enthrall’d by the powers of ill,/And, groaning and travailing, sighest/For better and happier still. Poem in full in Cork Constitution, 6 August 1857. 2 ‘It was my pleasure back in 1985 to represent the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) in dedicating an Engineering Milestone plaque to mark that wonderful technicalogical achievement. I can now report to you that the IEEE History Committee last year repeated that ceremony on the other side of the ‘big pond’ in the towns of Valentia, Waterville and Ballenskellics (sic) in Ireland. If you visit there anytime you will see similar plaques to the one that hangs on the wall of this museum’ (‘Connecting Continents’ by Dr Wallace S Read, P Eng) 3 A number of planning applications for building homes on the site was rejected in the years previous to 2003, dating back to the 1970s. The land was in the ownership of the O’Connell family of Knightstown for about one hundred years until the family sold the site in the 1960s. 4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ywSJ7-Qri9w. Junior Browne, properly Cornelius Joseph Browne, commissioned the documentary in 2010 and it was published on YouTube in 2011. It was filmed and narrated by Sean Mac An tSithigh, a Kerry based video journalist and features local historian Pat O'Shea, Mr Bill Burns of Atlantic Cable.com and Dr Bernard Finn of the Smithsonian institute. Cornelius Joseph Browne passed away on 6 August 2019. See obituary, ‘The Late Junior Browne, Dingle and late of Main Street, Castleisland, Co. Kerry,’ The Maine Valley Post, 7 August 2019. 5 See ‘Valentia Island site of first transatlantic message up for sale,’ The Journal, 24 July 2013. Peter Browne, proprietor of Browne’s Bar, Main Street, Castleisland, has operated his business in Castleisland since 2009; see http://www.brownesbar.com/. Peter can be contacted by email at peter.a.browne66@gmail.com. 6 Cork Daily Reporter, 22 July 1865. For further information about Foilhomurrum, see ‘Foilhomurrum: its Position in History’ on the O’Donohoe website. 7 Cork Daily Reporter, 22 July 1865. ‘For the purpose of completing the connection with the telegraph line already existing to and beyond Killarney, a new wire has been stretched along posts across the island of Valentia to the telegraph house adjacent to Foilhummerum creek.’ 8 Armagh Guardian, 1 September 1865. ‘Heart’s Content was to have been the American terminus of the Atlantic telegraph. There are various ways of reaching it, depending, of course, upon the place from which one starts but Halifax is the base from which all have to commence the final stage. Supposing it, however, to have been reached by what route soever, the following according to the New York Times is the sort of place the visitor will meet ...Civilized men, with garments of modern cut, unsoiled and whole, are to these ingenuous people pregnant with curiosity. No man appears upon the street from abroad without being accompanied to his place of destination by a throng of men, women and children. These cheerful people may be honest but their appearance belies their nature; they may be hospitable but their infernal bills contradict their generosity. They have been accustomed to regard the magnificent harbour which swells temptingly from the neck of land as a safe placing for bathing and an excellent reservoir for fish. Now that it looms before the world as one of the two main points in the history of the age, they transfer their regard for the water to the strangers who discovered its merits and in their anxiety to do them harm, became boresomely omnipresent and pecuniously exacting.’ The writer also added that hotels and boarding houses, ‘properly so-called,’ did not exist in consequence of which ‘a guard of swindlers’ was plundering ‘right hand aleft’ under the guise of lodgings. The writer also complained of the mosquito gnats, the most persistent and annoying ‘musicians’ this side of ‘the infernal band that sit in the gates of Hades.’ 9 Armagh Guardian, 1 September 1865, as extracted from the New York Times. 10 A full bibliography is beyond the scope of this work but the following may be of interest: The Atlantic Telegraph (1865) Sir William Howard Russell; Railways, Steamers and Telegraphs (1867) by George Dodd; The Story of the Atlantic Telegraph (1898) by Henry M Field; Submarine Telegraphs by Charles Bright (1898); The Story of Subsea Telecommunications and its Association with Endersby House (2005); The Irish Submarine Cable Stations A Technological History by Donard de Cogan, School of Information Systems, University of East Anglia, Norwich. ‘There has been a little discussion on both sides of the Atlantic concerning the precise person to whom honour is due as the originator of the scheme; but in truth there was no one such person, any more than there was one inventor of the steam-boat; many ingenious minds combined in various ways to work out a grand result… In 1855 Mr Field came to England and consulted Mr Brunel, Mr (afterwards Sir Charles) Bright, Mr Brett, Mr Whitehouse, and other experienced persons respecting the great cable and all that pertained to it.’ Dodd 11 Kerry Evening Post, 19 August 1857. It was also reported that ‘Mr E W Cooke, the well-known marine painter, is on board the Agamemnon, with a view to sketch the naval incidents of the voyage’ (Liverpool Mercury, 3 August 1857). Edward William Cooke (1811-1880). The Cooke Collection of drawings is held in the Institute of Engineering and Technology (IET), London. The collection was donated by Cooke’s son, Conrad William Cooke (1843-1926), in a letter, addressed from The Pines, Langland Gardens, Hampstead, London, dated 14 June 1915. The illustrations relate to the expeditions of 1857 and 1858. 12 It is worth noting that in 1854, the Illustrated London News commissioned Sir Oswald Walters Brierly (1817-1894), who would become a favourite of Queen Victoria, to take sketches of naval operations as a war artist. For further reference to the ‘special artist’ see The Pictorial Press: its Origin and Progress (1885) by Mason Jackson. John Raphael Isaac (1808-1870) also left an impressive collection of illustrations; see Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore A Series of Sketches drawn on the spot by John R Isaac (1857). Isaac also depicted the 1858 expedition. Further reference, https://atlantic-cable.com/Books/1857Isaac/index.htm. 13 ‘Towards the close of 1856 the Atlantic Telegraph Company was born ... A busy day was the 7th of August 1857. Six steamers were assembled in the usually quiet harbour of Valentia – the Agamemnon and the Niagara carrying the two halves of the cable; the Leopard, Susquehanna, Willing Mind and Advice ready to afford assistance. The shore-end of the cable was landed and received with some ceremony by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in a temporary telegraph-house on the beach.’ Dodd. 14 Kerry Evening Post, 5 & 8 August 1857. 15 Kerry Evening Post, 5 & 8 August 1857. 16 Kerry Evening Post, 5 August 1857. 17 The Second Volume of Harper’s Weekly, A Journal of Civilization, 1858, page ii. John McLenan (1827-1865), Augustus Hoppin (1828-1896) and Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1822-1888) numbered among the illustrators. 18 Cyrus W Field, Newfoundland, to the directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, London: ‘Entered Trinity Bay, noon, on the 5th; landed cable on the 6th. On Thursday morning, shipped at once to St John’s two miles of shore cable with end ready for splicing. When was the cable landed at Valentia? Answer by telegraph.’ In reply, the directors in England to the directors in America: ‘Europe and America are united by telegraph – Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace and good will towards men’ (Kerry Evening Post, 18 August 1858). The latter, part of a 31 word message, occupied 35 minutes in transmission. 19 Submarine Telegraphs (1898) by Charles Bright, pp47-48. The Telegraph House was built in Knightstown in 1857/1858. 20 Among the messages were two important official despatches sent to Canada countermanding the sending of two regiments to England: ‘August 31 1858. The Military Secretary of the Commander-in-Chief, Horse Guards, London, to General Trollope, Halifax, Nova Scotia. The 67th Regiment is not to return to England.’ ‘The Military Secretary of the Commander-in-Chief, Horse Guards, London, to General Commanding at Montreal, Canada. The 39th Regiment is not to return to England’ (Kerry Star, 18 March 1862). 21 Edward Orange Wildman Whitehouse, Electrician-Projector, writing from the Royal Institution, London, on 6 September 1858, gave his version of events in a letter to the editor of The Times. ‘As early as the fourth day after the landing of the cable at Valentia, I felt it my duty to urge in the strongest manner upon the directors, the immediate necessity for protecting the home end of our light and fragile cable, warning them of impending injury, and of the certain interruption of communication which would ensue therefrom. Of this no notice was taken by the directors’ (Kerry Evening Post, 11 September 1858). 22 Kerry Star, 18 March 1862. 23 ‘The shareholders who a few days since were in ecstasies of delight at the high price of their shares, are getting very low spirited’ (Kerry Evening Post, 11 September 1858). 24 Dudley performed as Mr Glass of Glass, Elliott & Co, manufacturers of the cable, in A Field Glass; Being a Cableistic and Eastern Extravaganza on board the Great Eastern in July 1866. An illustration of a scene from the play, perhaps from the pen of Mason Jackson, was published in the Illustrated London News, 28 July 1866, under title ‘Amateur Dramatic Entertainment on Board the Great Eastern Steam-ship at Sea.’ Dudley (as Mr Glass) may be the character holding a section of cable. Mr Glass – Richard Atwood Glass – was the managing director of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company. This company merged with the former Glass, Elliott & Co of Enderby House, Greenwich (Greenwich in 50 Buildings (2018) by David C Ramzan). 25 Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 17 June 1865. 26 Commercial Journal, 17 June 1865. 27 Railways, Steamers and Telegraphs (1867) by George Dodd, p286. 28 Penny Illustrated Weekly News, 5 August 1865. The editorial in full: ‘In Foilhommurrum Bay there assembled between three and four hundred men, picked from the finest peasantry in Europe, and capable of Herculean labours if their capacity and willingness for work could have been safely tested by the capacity and recklessness with which they used their lungs. The Caroline got her mainmast unshipped and was sent round on Thursday to Port Magee, which is the southern entrance to Valentia Harbour. Early in the morning, although the clouds lowered on the horizon, and the mists sailed densely over the mountain tops, and even kissed the higher cliffs, the sea was calm and the wind very light, so the Caroline was backed into the bay and anchored so that her stern was about three hundred yards from the shore. High on each side rose the steep and beetling cliffs of slate, blackened by exposure to the pitiless pelting of many an Atlantic storm; and in two places there wound down the face of the cliffs little zigzag paths made by the kelp gatherers. From either point, the bay presented a very pleasant picture soon after eight o’clock. And while the Caroline hardly moved to the gentle swell, the white steam floated lazily from her steam-pipe, and her decks were busy with energetic life. From right under her stern to the very shore there stretched two-and-twenty boats, from the smart cutter of the Great Eastern and the trim gig of the Coast-guard to the ordinary coast boat. Altogether there were some five and thirty boats engaged, and there were, perhaps, eight or ten men in each boat. Here and there, from the stern, floated a bit of bunting; but for bunting, real or imitation, the place to look was the top of the cliff on the right. All the pocket handkerchiefs, and a good many of the brighter shawls of the countryside, had been pressed into service for the occasion; and the northern cliff was certainly very gay, while, in all directions, rugged but rosy children, who seemed to thrive on fresh air and potatoes better than London youngsters do on the squares and the fat of the land, ran about and kept nervous people in perpetual fidget lest they should roll over the precipitous cliffs, and become food for crabs. A London child going where they went would have been smashed to pieces in five minutes; but they were guided by a surer instinct, and their mothers saw them running about where the grass feathers over the verge of the cliffs without betraying the least fear for their safety. Up the face of the cliff, in the loose earth which had fallen from above, and perhaps for a few inches into the soft slate, there was scraped a trench, and this trench was cut about two feet deep in the half-dozen yards or so that form the beach of the bay. Then, the thick end of the cable, being passed over the sternmost wheel of the Caroline’s paying-out machinery, which is that of the Great Eastern on a small scale, though with a larger groove in the wheel, was hauled ashore by a rope to which a hundred men laid what they perhaps would have called all their strength. At such a rate of pulling they would certainly not have got ashore an inch per hour if the cable had not been lightened over the interval between the ship and the shore by the men in the procession of boats. About half a mile was got on shore and coiled down on the beach; and once the enthusiastic Kerry men, who were more given to shouting and cheering than to hauling, having heard that there was a mark where the hauling ashore was to cease, came to a piece of rope-yarn that had been caught in the twist of the wire, and, Irish-like, jumping to conclusions, the half of them, without waiting for orders dropped the cable overboard. This caused some delay, and it was close to noon when a great cheer announced that the shore end was all ready. Just before this it was necessary that some one should go into the water, and immediately Mr Thomas Temple. One of Mr Canning’s engineering staff, jumped in up to his neck, and, with the help of a man who followed him, did what was required. And then the cable was laid in the trench above spoke of, and was hauled up the cliff, where enough had been laid in another trench dug from the face of the cliff to the telegraph operating house, the regiment of men being very enthusiastic, and shouting very much more than seemed necessary Here, in the presence of Sir Robert Peel, Lord John Hay, the Knight of Kerry, and a number of other more or less distinguished persons, the central wires of the thick shore end were connected with the speaking instrument, and a signal sent to and received from the Caroline. This difficult operation was, therefore, a success. Then, when this step in the communication had been secured, the Knight of Kerry, who has all along taken the greatest interest in the work, addressed to the throng a few words, expressing his satisfaction at the auspicious commencement of laying the cable. He called for three cheers for Sir Robert Peel and three more for the Atlantic cable. Sir Robert Peel then spoke of the political, social, and commercial benefits which would be secured if the cable should prove successful; and after invoking the aid of Divine Providence, called for three cheers for the Queen and three for Mr Glass, the managing director of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company. Mr Glass said that all human skill could achieve had been applied to the furtherance of the object which he hoped was now near its consummation. Sir R Peel having called for three cheers for the President of the United States, and the Doxology having been sung, Mr Glass formally announced the success of the test that had just been applied, and then the men returned to the beach and filled up the trench in which the cable lay. Soon after twelve, the Hawk arrived from Knightstown, and towed the Caroline out of the bay to lay the cable which was done at about two and a half miles per hour. Up to the present time, with one or two slight hitches, all appears to go on well, and daily we have the electric current informing us of the number of miles of cable already paid out of the Great Eastern.’ NOTE: John Thomas Dicks (1818-1881) was proprietor of The Illustrated Weekly News which commenced 12 October 1861 (not to be confused with Sir William James Ingram’s The Penny Illustrated Paper which also commenced on 12 October 1861 (edited by John Latey (1842-1902); ran until 22 March 1913; continued as London Life, run in conjunction with Illustrated London News). It was first printed by James Meldrum and published by Walter Lawry Molyneux. The last issue, no 423, appeared on 30 October 1869, then printed by Judd and Glass and published by E Griffiths. From 20 June 1863 its title changed to Penny Illustrated Weekly News until and including 12 January 1867 when it reverted to The illustrated Weekly News. Its first business address was 13 Catherine Street, Strand, the same offices as the short-lived Illustrated News of the World (edited by J M Moir, John Tallis and James Ewing Ritchie until it folded c1863, and of which John Tallis, Mount Pleasant House, Hornsey, London was proprietor from inception until 1861). 29 Cork Examiner, 25 July 1865 and Penny Illustrated Weekly News, 5 August 1865. 30 Great efforts were made to retrieve the cable. See Dodd, pp291-294. 31 Mason Jackson was appointed in 1860 on the death of Herbert Ingram. 32 William Henn, eldest son of Thomas Rice Henn, recorder of Galway, of Paradise Hill, Kildysart, Co Clare. He was married to Susan Matilda Cunninghame Graham Bartholomew (1853-1911), daughter of Robert Bartholomew of Ascog, Bute, but had no children. William Henn died from bronchitis at his father’s residence on 1 September 1894 aged 47. His brother, Francis Blackburne Henn (1848-1915), Resident Magistrate, Sligo, inherited his father’s estate. Further reference to the life of Henn, see ‘Hunting with the Amazons’ by Jeanne Willoz-Egnor at https://www.marinersmuseum.org/blog/2019/07/hunting-with-the-amazons/. 33 The Atlantic Telegraph Company was replaced by a new company, Anglo-American Telegraph Company, working with the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company and the Great Eastern Ship Company; see Dodd, pp294-5. 34 Liverpool Daily Post, 20 July 1866. ‘In this rambling whitewashed structure, which almost precisely resembles the Club-house at Aldershott on a small scale, there is a sanctum sanctorum called the instrument-room, a very small and carefully darkened apartment into which none enter but Mr Varley, or the one or two whom Mr Glass, on rare occasions, allows to see the scientific mysteries. There is very little to be seen, however, beyond a thin ray of light, fluctuating now slowly now rapidly and sometimes standing steadily still as it makes its dots and dashes along the graduated scale in front of it, and the most utter silence has to be preserved, that nothing may distract the attention of the operator in reading the thin, small gleams, for there are messages from the ship, which at any minute may prove to be of the last importance.’ ‘Mr Varley’ was Cromwell Fleetwood Varley (1828-1883), engineer and parapsychologist. 35 Tralee Chronicle 17 July 1866. 36 Ibid. 37 ‘The Great Eastern will coal comfortably from the 3rd or 4th of July till the 7th or 8th in Bantry Bay. From Berehaven the Great Eastern will go to Valentia, not later than the 10th of July and by that time the new shore end will be laid from the William Cory, and be ready at a buoy not far from the spot where the splice was made last year. When the ends of the new cable are joined, the Great Eastern, with her consorts, will take her departure for Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, on a course distant about thirty miles from that which she took last year, so that there may be no chance of laying the new cable over the old one’ (The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle for 1866, p384). 38 ‘In the evening the light of Fastnet was seen and the engines were slowed as we were compelled to lie off until daylight before entering the bay, there being no reason to run any risk by running in, in the dark. In the evening some of the passengers gave a theatrical performance in the saloon in the shape of a capital burlesque, entitled A Field Glass; or a Cableistic Extravaganza which had been composed on board and which dealt with the principal characters engaged in the expedition’ (Morning Post, 9 July 1866). 39 It was described as follows: ‘Neptune (Colonel de Bathe) is called upon in his home beneath the ocean by Mr Glass, to whom he expresses his entire disgust at all cables, and his determination not to permit the laying of the present one. Mermaids (capitally represented by Messrs Vaughan and Poore) sing to Mr Glass and beg him to stay with them. Mr Clifford, engineer (Lord Hastings) appears with a paying-out machine; and finally Mr Field (Captain Frank Bolton) appears on the stage, who at length, by various bribes of shares, satisfies Neptune, who goes off with him, and presently returns jolly drunk, having sold his shares at a good premium, and the cable is successfully laid, the performance closing with the mermaids picking up and reading the messages. The bill of the performance, which was capitally illustrated by Mr R C Dudley, was as follows: Steam-ship Great Eastern, July 1866. A Field Glass; being a Cableistic and Eastern Extravaganza by N A Woods and J C Parkinson, showing the inexplicable and vitrified adventurers of a Gurnet, a Milton Oyster, a Barbel, and Other Queer Fish, being an Un Varleys’d Tale of a Tank, after the manner of Thomson’s Seas-onable aid to Daniel’s profits on Elliot and Barclay’s Entire. By permission of Amphitrite And’er son James!’ (Morning Post, 9 July 1866). See same for cast. Synopsis also in London Evening Standard, 9 July 1866 and Illustrated London News, 28 July 1866, p94. 40 It was published in the Illustrated London News, 28 July 1866, under title ‘Amateur Dramatic Entertainment on Board the Great Eastern Steam-ship at Sea,’ the same issue that contained Jackson’s illustration of the fleet at Berehaven. Mason Jackson reproduced an edited section of the illustration in his book, The Pictorial Press: its Origin and Progress (1885) under title ‘A Cable-istic Extravaganza, performed by Newspaper Correspondents on Board the Great Eastern, at Sea, July 1866.’ 41 Tralee Chronicle 17 July 1866. A list of those present was given. 42 Sun (London), 27 July 1866. 43 The two men, along with Curtis Miranda Lampson (1806-1885), Samuel Canning (1823-1908), William Thomson (1824-1907) and Captain James Anderson (1824-1893), were knighted later that year; see Illustrated London News, 8 December 1866. 44 As there was not at that time good telegraphic connection between Heart’s Content and the mainland of America, the ‘Niger’ was despatched with the Queen’s message to a point whence it could be sent by wire to Washington. These various proceedings occupied the 29th and 30th July and on the 31st the operators at Heart’s Content received President Johnson’s reply to the Queen’s message, sent from the Executive Mansion, Washington to be forwarded to Osborne (Companion to the Almanac, Or Yearbook of General Information for 1867, p87. 45 Cork Constitution; or, Cork Advertiser, 30 July 1866. 46 Peter Wildbur (1927-2019), graphic designer, of BDMW Associates, Bloomsbury (founded in 1959 by Derek Birdsall, George Daulby, George Mayhew and Peter Wildbur), appointed graphic design consultants in the 1950s for Dublin company, Signa Design Consultants, established by Louis le Brocquy (1916-2012) and Michael Scott (1905-1989). Wildbur won the Glenabbey Award for the design of Tullamore Dew bottle, a project he shared with Louis le Brocquy. He began designing for Irish stamps in 1963, and a survey of his contributions is a sweep across Irish and world history. In 1963, his design commemorated the centenary of founding of Red Cross. His work in 1964 included centenary of birth of Wolfe Tone and the design of Facts About Ireland, published by Dept of External Affairs (reissued 1968/1969). In 1965 he designed the stamp to mark the centenary of founding of the International Telecommunications Union. His work in 1970 included 250th anniversary of yachting and foundation of Royal Cork Yacht Club (featured painting of sailing boats by Peter Monamy; he collaborated with Patrick Scott, B Arch MSIA); in the contemporary Irish art series, his design featured Madonna of Eire by Mainie Jellett; a stamp was also issued to mark the 50th anniversaries of deaths of patriots, Tomas MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney, Lords Mayor of Cork and the 50th anniversary of death of nationalist, Kevin Barry (1902-1920). In 1971 he adapted design of Europa stamp by Icelandic architect, Helgi Haflidason, for use on Irish stamps and in 1972, in the contemporary Irish art series, his design was on Black Lake by Gerard Dillon (1916-1971). In the 1974 Europa series, he designed Edmund Burke, from the statue by John Henry Foley, the bi-centenary of death of Oliver Goldsmith, also based on the statue by John Henry Foley and a Christmas stamp, Madonna and Child by Giovanni Bellini. Another Madonna and Child by Fra Filippo Lippi adorned his 1975 design. In 1976, the stamp recording the centenary of birth of James Larkin featured a drawing of Larkin, ‘Big Jim,’ by Sean O’Sullivan and also in this year was celebrated the American Bicentennial Year on the designs of Louis le Brocquy, graphics by Peter Wildbur. The 1978 US journal, Linns Stamp News featured stamps designed by Wildbur to be released in June of that year, based on drawings by Wendy Walsh. Two stamps issued in October 1978, the first celebrated the gas field discovered in 1971 off the Old Head of Kinsale, ‘the first of its sort ever’ and the second, a set of stamps to mark the 50th anniversary of the first issue of the first Irish currency since foundation of the Irish State in 1922 (four of eight coins depicted from drawings by Ron Mercer). More designs on the drawings of Wendy Walsh appeared in 1979, as well as the Europa series (depicting of the first transatlantic cable, Valentia,1866 and Bianconi) and European Communities. This was followed in 1980 by the centenary of the arrival in Ireland of the De La Salle Order, based on a portrait of John Baptist De La Salle. The Irish Fauna and Flora series of drawings by Wendy Walsh also appeared, as well as a new series, ‘Ireland,’ based on paintings by John Dixon. Later in 1980 a centenary of the birth of Sean O’Casey stamp, 12th in the contemporary Irish art series, featured Wildbur’s design from a photograph by Gjon Mili in Life Magazine of 1964. Wildbur’s work on the 1981 Science and technology series included designs of Harry Ferguson, Robert Boyle, Charles Parson and John Holland. The contemporary Irish Art series depicted William John Leech’s painting, ‘Railway Embankment’ and also in this year, work based on paintings of horses (Arkle, Boomerang, King of Diamonds, Ballymoss, Coosheen Finn) by Wendy Walsh; Nativity by Federico Barocci and an abstract design of marking the 250th anniversary of RDS. In 1982, the 50th anniversary of Killarney National Park (based on photographs taken by the OPW) was commemorated; The Stigmatization of St Francis by Sassetta; and the Europa series commemorated the Great Famine and the coming of Christianity of Ireland, St Patrick preparing the Paschal fire. Other works in 1982 included honouring Irish literary and musical figures: birth centenaries of Padraic O Conaire, James Joyce, bicentenary of birth of John Field and centenary of death of Charles Joseph Kickham. The Flora and Fauna series featured fish, on drawings by Wendy Walsh. Also in 1982, the bicentenary of Grattan’s Parliament and centenary of birth of Eamon de Valera (Wildbur designed the 22p stamp, from an oil painting by Francis Wheatley, ‘The Irish House of Commons’). In 1983, the bicentenary of Dublin Chamber of Commerce, featured the Ouzel Galley Goblet and the Europa series, Great Works of Human Genius, included Newgrange, work of Louis le Brocquy, and key formulae in multiplication of quaternions by Wildbur. The Christmas stamp was La Natividad by Roger van der Weyden. In 1984 three stamps issued to mark Ireland’s Olympic gold medal achievements from brush drawings by Louis de Brocquy, celebrated achievements of Pat O’Callaghan, Derryballon, Co Cork, in winning two gold medals; Bob Tisdall of Nenagh, Co Tipperary, and Ronnie Delaney, Arklow, Co Wicklow. Also in 1984, two stamps to mark the 500th anniversary of the establishment of Galway as Mayoral City and 1500th anniversary of birth of Saint Brendan the Navigator. The Christmas stamp was based on a painting of Virgin and Child by Sassoferrato. 47 Cork Constitution; or, Cork Advertiser, 30 July 1866. 48 Pitcher’s depiction of the Great Eastern lowering the grapnel for the lost cable was published in Herbert Strang's Annual of 1923 alongside an article, ‘Laying and Repairing the Submarine Cable’. Both were his work. 49 Illustrated London News, 13 October 1866. Further reference to the telegraph field, see ‘Fifty-two Degrees North: Calculating Castleisland’s Place in Longitude History’ and ‘Foilhomurrum: Its Position in History’ on the O’Donohoe website.