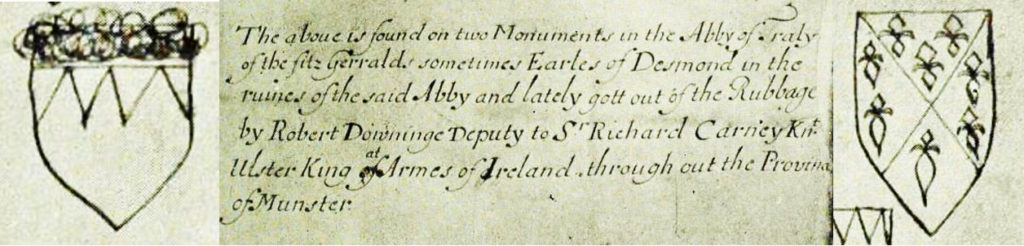

In the closing quarter of the seventeenth century, a series of sketches was taken from two stones found in rubble in Tralee Abbey. They were made between the years 1684 and about 1692 by Robert Downinge, Deputy to Sir Richard Carney.[1] The curious illustrations were captioned by Mr Downinge:[2]

The above is found on two Monuments in the Abby of Traly of the FitzGerralds sometimes Earles of Desmond in the ruines of the said Abby and lately gott out of the rubbage by Robert Downinge Deputy to Sr Richard Carney Knt Ulster King of [at] Armes of Ireland through out the Provina of Munster.[3]

In 1754, Fr Thomas De Burgo visited the site during the compilation of a history of the Irish Dominican Order and also described what appeared to be the same relic.[4]

Downinge’s manuscript found its way into the British Museum. In the nineteenth century, Archdeacon Rowan of Tralee and his daughter, Miss A M Rowan, both viewed it there (at different times) and both wrote about it.[5] Miss Rowan described it in her 1895 memoir of Tralee:

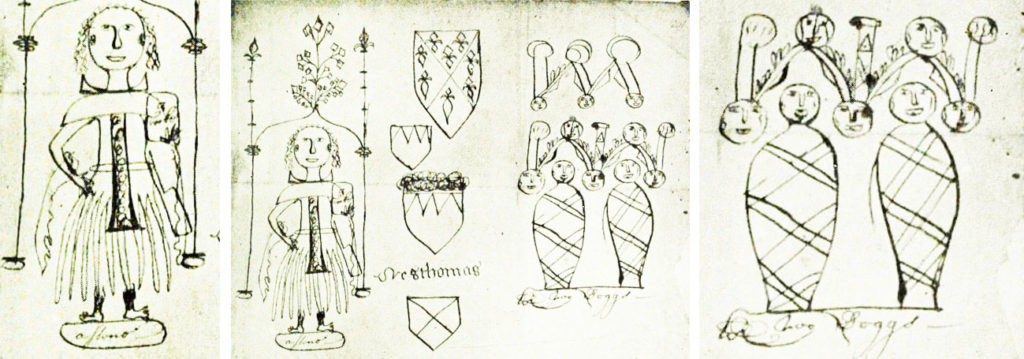

On the left hand of the sketch is the figure of a woman standing on a stone. She wears a coife, has a square yoke and high collar to her dress, on the body of which and going down the skirt with the arms across her waist, is a large cross. One arm, the right, is akimbo. In the left hand she holds a large book, which she is reading. On either side of her are delicately fluted pillars, with arch and pinnacle overhead, forming the niche in which she stands. On her left, outside the niche, is a flat space, on which are three shields, one over the other. The largest is on top. The field is quartered diagonally, three fleur de lis in the top, one in the bottom, and two in each compartment – the Desmond coat of arms.[6]

Miss Rowan, who recalled that her father often wondered what had become of the handsome stones, remarked on the ‘two little swathed figures, like infant mummies, standing upon two recumbent dogs.’[7]

In 1907, Reverend Sir Henry Lyttelton Lyster Denny published an article about Tralee Abbey.[8] He described how in Tralee in the mid eighteenth century, ‘many sepulchral stones’ from the ruined abbey could still be seen on the site or in the streets around it, and one of particular note showed ‘the effigies of two infant twins, traditionally said to be children of a Geraldyn Lord.’[9]

Rev Denny, then Minor Canon of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, identified the relic – from the few half defaced letters: ‘C res Thomas’ – with the wife and infant children of Thomas, Earl of Desmond, who died AD 1534.[10]

His conclusion mirrored that of Archdeacon Rowan.[11] If the carvings from the two relics were connected, and portrayed the Countess Desmond, wife of Thomas, Earl of Desmond who died in 1534, and two of her children, the deaths of the minors were evidently of some significance.[12]

Thomas, The Bald – Earl of Desmond, Died AD 1534

Thomas, generally known as Sir Thomas the Moyle, or Maol (Bald), was born in 1454, son of Thomas, The Great Earl and his wife, Elizabeth Ellice, daughter of William de Barry, 8th Baron Barry.

Mogeely Castle, two miles from Tallow, about which a legend is told of its intentional burning, was a residence of this earl.[13] He was twice married, first into the McCarthy family:

Thomas married Sheila, daughter of Cormac Láidir McTeige McCarthy, Lord of Muskerry, with whom he had issue one son, Sir Maurice, who died in 1529.[14]

It is far from clear if the wife of Thomas, daughter of Lord Muskerry, was named Sheila. In Lodge’s genealogical records, it is found that Sheila had married three times, her third husband, Lord Dunboyne.[15] In other records, the first wife of Thomas is named Ellen, though her relationship to the Lord of Muskerry is not disputed.[16]

Sheila or Ellen, daughter of Cormac Láidir McTeige McCarthy, Lord of Muskerry, was born in Cork in 1453. Her father, Láidir ‘The Strong,’ came into the lordship in 1449, and he and his descendants are credited with the foundation of many buildings in Cork including Kilcrea Castle, Kilcrea Abbey (where Lord Muskerry was interred in 1494), Carrignamuck (or Dripsey) Castle and Blarney Castle.[17]

The year of Sheila (or Ellen’s) death is not known, though it can be calculated to have occurred almost two centuries before Robert Downinge discovered the relics in the rubble in Tralee in the late seventeenth century. History has left us with the name of one child, a son, Sir Maurice Fitzthomas Fitzgerald, who died from the plague, in adulthood, in 1529.[18]

The second marriage of Thomas The Bald does not add clarity to his marital past nor does it cast light on the twin effigies. He married Catherine, daughter of Sir John FitzGerald, Lord of the Decies. Her place in history is the subject of continued scholarly debate. Tradition tells that Countess Catherine fell out of a cherry tree at the age of about 140.[19]

Thomas, 11th, 12th or 13th Earl (depending on source consulted) died at Rathkeile (Rathkeale) in 1534, ‘being of a very great age’ and was buried in Holy Cross (Our Lady of Graces) Dominican Abbey, Youghal, Co Cork.

Thomas, The Great Earl – Earl of Desmond, Died AD 1467 or 1468

Perhaps a more credible contender for the relics found in Tralee Abbey is Thomas The Great Earl, father not only of Thomas The Bald but also of Earl James (died 1487) Earl Maurice (died 1520) and Sir John of Desmond (died 1536) whose son Earl James (died 1558) was father of Gerald, The Rebel Earl, slain in 1583.

Thomas The Great Earl was the son of Earl James, The Usurper (died 1462) and Mary Burke (Clanricarde). In 1463, he was ‘nearly forty years of age’ on his appointment as Deputy Lieutenant of Ireland to George Plantagenet (1449-1478) Duke of Clarence (who was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1462).[20]

This gives Thomas a date of birth of circa 1423. He married, as far as can be seen, just once, to Elizabeth Ellice (1431-1486) daughter of William de Barry, 8th Baron Barry and Ellen de la Roche.[21] They married in 1455 and had seven children.

The accomplishments of Thomas were recorded thus:

Thomas was described in the annals as valiant and successful in war, comely in person, versed in Latin, English and Gaelic lore, affable, eloquent, hospitable, humane to the needy, a suppressor of vice and theft, surpassingly bountiful in bestowing jewels and wealth on clerics and laymen, but especially munificent to the antiquaries, poets and men of song of the Irish race. He founded a college church at Youghal, and at his suggestion parliament passed an act to establish a university on the plan of Oxford at Drogheda, which for want of endowments never grew up. He was ostentatious and liked to be surrounded by Irish chieftains who attended his court and were attached to him for his personal qualities, hereditary gossipred, fosterage or similar ties.[22]

It has been suggested that the downfall of Thomas The Great Earl was over a woman.[23] It was told that King Edward, against the advice of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, to marry Bona of Savoy, sister of the Queen of France, married instead Elizabeth Woodville (otherwise Wydville/Widville), widow of Sir John Grey (who was slain in the second battle of St Albans).

The Great Earl, in confidential chat with the king, was asked what the people thought of this union, and he replied that it was frowned upon but that it was not too late to reconsider his position and make a more favourable match:

If it shall please your Grace to pardon me and not to be offended with that I shall say, I assure you I find no fault in any manner of thing, saving only that your Grace hath too much abased your princely estate in marrying a lady of so mean a house and parentile; which though it be perchance agreeable to your lusts, yet not so much to the security of your realm and subjects.[24]

King Edward, during a subsequent quarrel with the queen, expressed regret he had not ‘taken the advice of Desmond.’

So sealed the fate of The Great Earl. The queen, enraged that the earl did so rebelliously talk of the queen, contrived to have him replaced as Deputy Lieutenant of Ireland by Sir John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester – ‘the butcher of England’ – who quickly brought Thomas and others to parliament on charges of treason.[25]

Thomas responded in person to the accusations and was arrested. Very soon after, he was beheaded.

Grey Areas

The place of execution, year of execution, and site of burial of The Great Earl differ in the historical record. According to the Book of Howth, the Earl of Desmond was executed in Dublin and immediately after, the Earl of Worcester went to Drogheda and executed the earl’s two sons.[27]

Immediate after the Earl of Willsyre (Worcester) went to Drogheda, where as was two of the Earl of Desmond his sons at learning. The eldest, scarce at the age of 13 years, there was beheaded. The youngest brother, being like case to be executed, having a bill of fellone (felony) upon his neck, said to the persecutor (executioner) these words, ‘Mine own good gentle and beloved fellow, whatsoever else ye do with me, hurt not nor grieve not this sore that is upon my neck, for it troubleth me and grieveth me very much; therefore take keep thereof.’ And with that, the innocent’s head was stricken off, for which cause those that stood by, did much lament. At which time there was such a shower of rain and wind as Heaven and Earth had contended together, that the like was not seen of a long time before, which was thought by those that there was that God was offended with shedding those innocents’ blood.[28]

In other accounts, Drogheda is named as the place of execution of the earl.[29]

The Carew Manuscripts, and many other sources, record the year of death as 1467 ‘anno 7 Edw IV’.[30] The date 15 February 1468 is also commonly given.

The Great Earl’s place of burial is also unclear. The historian, Amory, described how the remains were carried across the country to Tralee for interment, his death greatly mourned by the people.[31]

Elsewhere, the place of burial is given as St Peter’s Church, Drogheda, and subsequently Christ’s Church Cathedral (Church of the Holy Trinity) Dublin:

Among the monumental tombs in the cathedral that reputed to belong to Earl Strongbow is deserving of notice. It represents that powerful warrior in a recumbent position clothed in mail, with Eva, his wife, by his side. The female figure, however, is defaced. Some doubts are entertained of the authenticity of the figure of Strongbow, it being affirmed that it represents the Earl of Desmond, Lord Chief Justice, who was conspired against by those who looked with jealousy on his kindness to the Irish people, and beheaded at Drogheda in 1467. It is stated that Sir Henry Sidney had it removed to its present position in 1569.[32]

All Things Considered

The troubling execution of the earl and the slaughter of his two sons caused great ‘sorrow and affliction’ which ‘shocked the whole of Ireland … not only Ireland but the whole of Europe as far as Rome.’[33]

This might better explain how a carved impression of the countess, widowed in such circumstances, and the similar sized sarcophagi of her two children, came to find place in Tralee Abbey.[34] The horrific events demanded a lasting impression. The carvings may have done just that.

In 1895, Miss Rowan left one small gem in her description of the manuscript:

I give this lengthy description of this old monument because quite recently my attention was drawn by Miss Huggard to a curious old stone built in the north wall of the south-west aisle of St John’s Chapel. Upon comparison with these sketches, it proves to be the remains of this handsome monument, the portion built into the wall being the swathed figures of the two children with their feet upon the recumbent dogs and a portion of the niches over their heads.[35]

In 1960, St John’s Chapel, Tralee, otherwise St John the Baptist Church, was renovated, the internal walls stripped of plaster, and the stonework pointed. However, the sculpture survived and is today found above the inside entrance to the baptistry.[36]

The fate of the second stone depicting the countess is not known.

_______________________

[1] The date of composition has been calculated by the year in which Sir Richard Carney was knighted, 1684 (at which time the sketch artist was his deputy) and the year in which he died, 1692 (or early 1693). The following is from A Dictionary of Irish Artists (1913): Sir Richard Carney was made Principal Herald of Arms of the whole Dominion of Ireland in 1655, an office he held until 1660. After the Restoration, he was appointed, in 1661, Athlone Herald and made Ulster King of Arms in 1683. He was knighted in 1684. He was married to Lettice, daughter of Thomas Tallis, Muster-Master-General of Ireland (perhaps the same Thomas Tallis described in 1636 as ‘late cleark of the municons under his Lordship’ in the Lismore Papers, viz, Autobiograhical Notes, Remembrances and Diaries of Sir Richard Boyle, First and ‘Great’ Earl of Cork, Vol IV 1886), and was father of Richard Carney. He died in 1692. In that year, his son was Ulster King of Arms. [2] Members of the Downinge family are mentioned in Miss Rowan’s 1895 memoir (Memories of Old Tralee, reproduced in 2016) including Sir George Downinge, East Hatley, Cambridge (1663), ‘Leeftennnt Downinge’ placed in charge of Doneraile Castle in 1627 by the Lord President of Munster and who died in 1629 (his wife was Catherine, daughter of Sir Valentine Browne, Molahiffe, Co Kerry); Tom Downinge whose family was massacred; Robinge (Robert) Downinge coronet to Lord Broghill in 1641. And ‘the last of the line’ Elizabeth Downinge who married William Godfrey Esq, Kilcoleman Abbey, Milltown. A Robert Downinge is mentioned in the year 1633/1634 in the Lismore Papers, viz, Autobiograhical Notes, Remembrances and Diaries of Sir Richard Boyle, First and ‘Great’ Earl of Cork, Vol IV 1886, p19. [3] From a manuscript held in the British Museum, reproduced in ‘Tralee Abbey’ by Rev H L L Denny (Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead, Ireland (1907), pp360-379). In Rev Denny’s article, the illustration was captioned ‘Old Sketches of the Fragments of a Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond, Tomb, Formerly in Tralee Abbey [The photograph of the manuscript in the British Museum has been obtained for the Journal by Mr Peirce G Mahony, Cork Herald of Arms.]’ [4] Hibernia Dominicana Sive Historia Provinciae Hiberniae Ordinis Praedicatorum (1762). The text, in Latin, ‘Ur autem Traleiam regrediamur, quamquàm Solo prorsàs aequata sint Templum, & Caenobium, Traleiensibus in Sitûs eorum Parte, ceù in Platea, hinc inde discurrentibus, plures nihi-iominùs etiamnùm visuntur Lapides Sepulchrales, unus nominatim Effigies duorum Infantium Gemellorum, quos Traditio adjudicat Domui Geraldinae, clarè distincteque exhibens. Etsi porrò incertum sit, quo Tempore dirutae fuerint Aedes sacrae, crediderim tamen, eas, regnante Jacobe II, aliquatenùs extitisse, eò quippè Loci vidi nuper (Anno 1754) Tumulum adhuc erectum cum sequenti Inscriptione, Anglicanis Verbis conceptà …’ (p240). [5] Archdeacon Rowan’s article, abridged from the Kerry Magazine 1854, appeared in the Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 2 no 11 (Oct 1913) pp141-150, ‘Tralee Castle and Abbey.’ [6] Memories of Old Tralee, reproduced in 2016, p84. Miss A M Rowan noted that her father had sketched this item in the British Museum (ADD MSS 4820 BM) in 1848, as she had herself in 1884. [7] On closer inspection, Downinge’s wording appears to be ‘hog Boggs’ perhaps a seventeenth century term for the animals on which the effigies stood. They do not appear to be dogs but look more like elephants. Perhaps an expert in the field of medieval funeral architecture could add more. [8] ‘Tralee Abbey’ (Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead, Ireland (1907) by Rev H L L Denny, pp360-379). [9] ‘Tralee Abbey’ by Rev H L L Denny (Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead, Ireland (1907) pp361-362. ‘In 1756, little remained of Tralee Abbey but for ‘a few vaults still standing’.’ [10] He added, ‘In Lodge’s Peerage, Thomas, 12th Earl, is said to have been buried at Youghal; and if this be correct, the monument would probably belong to his infant sons and his Countess. All his children predeceased him, and he was succeeded by his grandson James as 13th Earl.’ Rev Denny’s article (p361) included a list compiled by Archdeacon Rowan which showed a number of Earls of Desmond buried in Tralee Abbey during the thirteenth, fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. The earls were John of Callan AD 1261; Maurice FitzGerald AD 1261; Thomas An Appah FitzGerald AD 1355; Maurice (1st Earl of Desmond) AD 1355; Maurice (2nd Earl) AD 1358; Maurice 10th Earl AD 1520; James 11th Earl AD 1529; James 13th Earl AD 1535; John 14th Earl AD 1536; John 15th Earl AD 1558. Notes on the Earls of Desmond buried in Tralee Abbey also contained in Tralee Abbey and Holy Cross Dominican Church A Brief History by Rev John C Ryan (1897, 2018), ‘The Geraldines’ pp11-18. Regarding the sometimes confusing count of the earls, see http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-earls-of-desmond-a-headcount/ [11] As remarked by Miss Rowan in her memoir, ‘He [my father] fancied it might be a monument erected by the 12th Earl to his wife, Elinor Butler, and twin children, he himself being buried at Youghal in 1524.’ [12] Sir Henry Lyttelton Lyster Denny, 7th Baronet, was Rector of St Bartholomew’s, Burwash, East Sussex in 1936. He was the author of A Handbook of Co Kerry Family History (1923). He died suddenly after an operation in 1953 at the age of 74. ‘Sir Henry succeeded to the Baronetcy on the death in Edmonton, Alberta, of his uncle in 1929. He was a descendant of the Sir Anthony Denny who was executor of Henry VIII, and who figures in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. Sir Henry leaves four sons. Heir to the Baronetcy is Anthony Coningham De Waltham Denny’ (obituary, Evening Echo, 4 May 1953). ‘Sir Henry was a hereditary Freeman of Cork City and was founder, Vice-President and Hon Secretary of the Kerry Society. He was educated at Arlington School, Portarlington and at TCD. He was ordained in 1902 and was appointed a minor canon of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin in 1907’ (Irish Independent, 5 May 1953). [13] The Percy Anecdotes: Original and Select (1826 ) by Sholto Percy and Reuben Percy ‘Earl of Desmond’ pp113-114. The legend relates how the earl’s steward, unknown to the earl, invited a great number of chiefs of Munster to spend a month at the castle. They arrived, to the great surprise of the earl, who soon ran short of provisions for their stay. His pride would not allow him to let his guests know of the situation and so he invited them to hunt and instructed his servants to set fire to the castle in their absence. [14] Biographical Dictionary of Lower Connello (2012) by John M Feheney. ‘Thomas became earl on the death of James in 1529.’ Sir Maurice Fitzthomas Fitzgerald died in 1529 from the plague: ‘Only son Maurice, who dying of the plague at Rathkeale, in the county of Limerick, within six months after the Earldom fell to his father, was buried at Youghall. Maurice left by Joan, daughter of John (the White Knight) Fitz-Gerald, James, successor to his grandfather in 1534’ (Pedigree of the Earls of Desmond in The Peerage of Ireland: or, A Genealogical History of the Present Nobility of that Kingdom (1789) by John Lodge, Deputy Keeper of the Records in Birmingham Tower revised and continued by Mervyn Archdall, Rector of Slane, Vol I, ‘The Family of Desmond,’ pp63-77). James, The Court Page, 12th Earl of Desmond, died in 1540. [15] The genealogical records of John Lodge conflict in the record of the first wife of Thomas, Earl of Desmond. In his record of the Earls of Desmond, he wrote, ‘Thomas is said to have married Shelah (or Julia) daughter of Cormac MacCarthy, Lord of Muskerry, but more probably her daughter Elinor, by her third husband Edmond, Lord Dunboyne’ (Pedigree of the Earls of Desmond in The Peerage of Ireland: or, A Genealogical History of the Present Nobility of that Kingdom (1789) by John Lodge, Deputy Keeper of the Records in Birmingham Tower revised and continued by Mervyn Archdall, Rector of Slane, Vol I, ‘The Family of Desmond’ pp63-77). In his record of Lord Dunboyne, he wrote: ‘Sir Edmund Butler, first Lord Dunboyne married Gyles, Julia, or Cicely, daughter of Cormac Oge Mac-Carthy of Muskerry, widow of Gerald the fifteenth Lord of Kerry, and of Cormac-Na-Hony Mac-Carthy Reagh, and by her (who 27 July 1551 had a licence to go into England) he had issue three sons and two daughters, viz, James, his successor; John (who married Ellen, daughter of Thomas Purcell of Loghinoe, Co Tipperary); Pierce (who married Ellenor, daughter of Oliver Grace); Ellenora, married to Gerald, Earl of Desmond and Catherine, married to Terence Magrath’ (The Peerage of Ireland: or, A Genealogical History of the Present Nobility of that Kingdom (1789) by John Lodge, Deputy Keeper of the Records in Birmingham Tower revised and continued by Mervyn Archdall, Rector of Slane, Vol VI, ‘Butler, Lord Cahier’pp215-235). Elsewhere, it is seen that Catherine Barry married Cormac Oge (1447-1537) Lord of Muscry, son of Cormac Laidir, with issue Teige and Julia, who was married three times, first to Gerald Fitzmaurice, Lord of Kerry; secondly to Cormac MacCarthy Reagh of Kilbrittain Castle and thirdly to Edmond Butler, Lord Dunboyne (Irish Pedigrees; or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation (1892) by John O’Hart, Vol I, ‘Lords of Muskry’). [16] ‘Thomas, the thirteenth Earl of Desmond, brother to Maurice, the eleventh earl, died this year, 1534 … He married first Ellen, daughter of M’Carty of Muskerry by whom he had a son, Maurice’ (Memoirs of Eminent Englishwomen (1844) by Louisa Stuart Costello, Vol 3, p26). [17] ‘A celebrated Franciscan monastery was founded at Kilcrea by Cormac Mac Teige Carthy under the invocation of St Bridget in 1464 (the Ulster Annals assign 1478 as the date), who dying in 1494 was buried in the middle of the choir. His tomb bore the following inscription: Hic jacet Cormacus fil. Thadei fil. Dermitii Magni Mac Carthy, Dom. De Musgraigh Flayn, ac istius conventus primus fundator, an. Dom. 1494.’ ‘Archdall (referring to Ware) says that he was murdered by his brother Owen, and Smith that he was wounded at Carrignamuck. Several of his family were also interred here, viz, Cormac Mac Teige Carthy, called Laider, or the Strong, who founded it, as above; Cormac Oge Laider, his son, buried here in 1536. He fought the celebrated battle of Mourne Abbey where he vanquished the Earl of Desmond; Teige, his son, Lord Muskerry, buried here 1565. He was father to Sir Cormac Mac Teige; Dermot, his son, buried here an. 1570, ancestor of the Mac Carthys of Inshirahill. Cormac, his son, buried 1616, who had been some time a Protestant, and was the last lord of this family here interred … Blarney Castle was built by Cormac Mac Carthy, surnamed Laider (who came into the lordship in 1449, according to Smith, History, Vol I, p166). He also built the castles of Kilcrea and Carrignamuck, the Abbey of Kilcrea, the Nunnery of Ballyvacadane, and five churches. He was wounded at Carrignamuck by Owen, the son of Teige Mac Carthy, his cousin-german, and died at Cork, being buried in Kilcrea, as we have seen above’ (‘On a Manuscript Description of the City and County of Cork, cir. 1685, Written by Sir Richard Cox’ by Swift Paine Johnston and Colonel T. A. Lunham, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No. 4, [Fifth Series, Vol. 12] (Dec. 31, 1902), pp. 353-376). [18] See note 14 above. [19] The story is often given by the guides during tours of Muckross House, Killarney, where a portrait of Catherine hangs in the drawing room. Catherine’s ancestry is given thus: Sir John, son of Gerald by Margaret, daughter of Mac Richard Butler, had by Ellen Fitzgibbon, Catherine, widow of Thomas Maol, 12th Earl of Desmond. An account of The Old Countess is given in History Ireland, Vol 21, Issue 3, May/June 2013, ‘The Old Countess, the Geraldine Knight and the lady antiquarian: a conspiracy theory revisited.’ [20] Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207. Thomas, Earl of Desmond, in 1463 deputy to the Duke of Clarence, succeeded Sir Rowland Eustace (Lord of Port Lister, and Viscount Baltinglass, Lord Deputy to George Duke of Clarence, who was made Lord Lieutenant for life) and preceded by Thomas Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, Lord Deputy. Reference, The New Peerage; or Present State of the Nobility of Ireland … To Which is Added A List of Extinct Peers and An Account of the Chief Governors of Ireland (1769), Vol III, ‘A Chronological Table of the Chief Governors of Ireland, from the conquest thereof by the English in 1172, to the Year of our Lord 1768,’ pp254-270. [21] ‘His wife was Elizabeth Barry, daughter of the viscount Buttevant, and her sister [Catherine] had married Cormac Laidir McCarthy’ (Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207). Cormac Oge Muscry MacCarthy Reagh (1447-1536) married Lady Katherine Oge MacCarthy (nee Barry, born 1456). The pedigree of the Earl of Clancarty to Oilioll Olum in given in The General History of Ireland (1723) by Geoffrey Keating, ‘The Genealogy of the Posterity of Heber Fionn.’ [22] Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207. [23] The woman in question was Elizabeth, wife of King Edward. In her book, The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family (2013) author Susan Higginbotham dissected the charge against Queen Elizabeth and concluded that ‘The story that Elizabeth procured Desmond’s death, in short, rests on mighty shaky ground.’ [24] Ibid. See also Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts (1868) by J S Brewer, Introduction, Appendix cv-cviii. ‘The Earl of Desmond should have been apprehended and taken, and his head struck off in example of other which rebelliously would talk of the Queen as he did’ (Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, Preserved in the Archiepiscopal Library at Lambeth (1871) Edited by J S Brewer MA and William Bullen Esq, ‘The Book of Howth’). [25] John Tiptoft (or Tibetot) (1427-1470) 1st Earl of Worcester, Lord Treasurer and Lord Constable, did not long survive the Earl of Desmond. He was arrested in Weybridge Forest, Hunts, where he had been hiding in a tree, and taken to the Tower on a charge of cruelty. He was beheaded on 18 October 1470. [26] Depiction of Edward IV after an original painting in the Royal Collection published in The Goldsmith’s Wife by William Harrison Ainsworth; Elizabeth Widville, traced from a window in Thaxted Church Essex, from Original Letters written during the Reigns of Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III and Henry VII (1823); reverse of Great Seal from The Student’s Hume A History of England (1884) by J S Brewer, Part I, ‘From the Earliest Period to the Death of Richard III’; Bermondsey Abbey from John Cassell’s Illustrated History of England (1858) by William Howitt, Vol II, ‘From the Reign of Edward IV to the Death of Queen Elizabeth’; King Edward and Jane Shore from History of Jane Shore Concubine to King Edward IV (1825). [27] Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, Preserved in the Archiepiscopal Library at Lambeth (1871) Edited by J S Brewer MA and William Bullen Esq, ‘The Book of Howth’ p187. [28] Ibid. According to Richard III, the earl had been ‘extorciously slain and murdered by colour of the law … against all manhood, reason and good conscience’ (The Making of Ireland From ancient times to the present (1998) by James Lydon, Ch 6, ‘The Geraldine supremacy’). [29] He was confined in the Dominican Friary in Drogheda from where he was taken on the 15th of February 1468 and decapitated ‘the queen attaching, surreptitiously it is said, the royal seal to the warrant’ (Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207. [30] Carew Manuscripts, p439. [31] Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207. [32] Black’s Guide Books for Tourists Dublin and Wicklow Mountains (1875) p21. [33] Transfer of Erin or The Acquisition of Ireland by England (1877) by Thomas C Amory Ch XXIV Reign of Edward IV (1461-1483) pp190-207. [34] After the tragic death of her husband, the Countess Desmond married again to Maurice Mor Fitzgibbon, 6th White Knight. She died at Dromana House, County Waterford, in 1486. [35] Memories of Old Tralee, reproduced in 2016, p85. [36] From booklet, Church of St John the Baptist, Tralee, Co Kerry, Ireland A Visitor’s Guide, revised and published a few years ago. The foundation stone of this church was laid in 1854. With kind thanks to Fr Tadhg Fitzgerald of St John’s Church for allowing access to the baptistry for photographs during the current Covid19 lockdown.