Longitude: the angular distance of a place east or west of the Greenwich meridian, or west of the standard meridian of a celestial object, usually expressed in degrees and minutes

Those who avoid the subject of maths might find the above definition of longitude explanation enough when it comes to global measurement. Those who find the subject absorbing, however, might be interested to learn about Castleisland’s link to this fascinating subject.

The Longitude Field in Foilhomurrum, Kerry, site of a nineteenth century observatory, is currently in the ownership of Peter Browne of Castleisland. It was purchased by Peter’s father, the late Junior Browne, in 2003.[1]

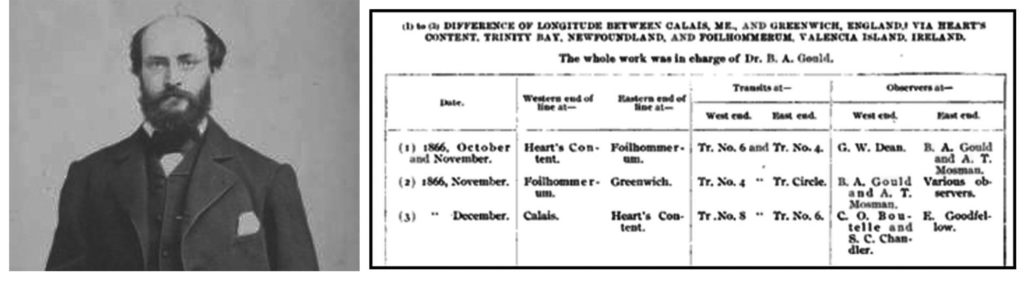

In this field, more than 150 years ago, the eminent astronomers Dr Benjamin Apthorp Gould, Alonzo Tyler Mosman and Professor Benjamin Peirce studied the stars.

Peter has continued the research begun by his father into the widening history of the field, and has amassed a number of valuable documents about the historic site, once also home to a telegraph hut, a cable house and a police hut.[2]

Telling the Time

The implications of global time differences became apparent in the wake of the successful cable link from Foilhomurrum Bay to Heart’s Content in 1866. One French paper made the point in a humorous way.

Supposing, said the writer, the Paris opera house burned down at a quarter past twelve at night on 1st September 1866. The event is immediately telegraphed from Paris to New York and is dated, Paris, a quarter-past twelve at night, 1st September. The news arrives in New York at a quarter-past nine in the evening of the 31st August so that a New York manager could appear on the stage and after three customary bows, say:

Ladies and gentlemen, I am sorry to have to inform you that the opera at Paris has been destroyed by fire three hours after the present time. Our director has just transmitted to his Paris confrere his condolence on the disaster that is going to happen to him.[3]

The same writer drew attention to the importance of longitude, stating that New York was 76 degrees of longitude west of Paris.

At the same time, astronomer Monsieur Jacques Babinet (1794-1872) was also discussing longitude. He addressed a meeting of the Academy of Science in Paris. Remarking on the recent success of the transatlantic cable, he outlined his belief that the project would be short-lived due to the corrosive action of sea water on the cables.[4] For this reason, he urged that advantage should be taken to determine the accuracy in the longitude of the American station:

We should profit, and that at once, by the electric cable, which unites the New World and Valencia, to determine the exact longitude of the American station, for there is very little chance indeed that messages can be sent for any long period. It will be recollected that in 1858 the cable transmitted the electricity for a few days only and that it took 30 hours to send 51 words.

Longitude of Foilhomurrum

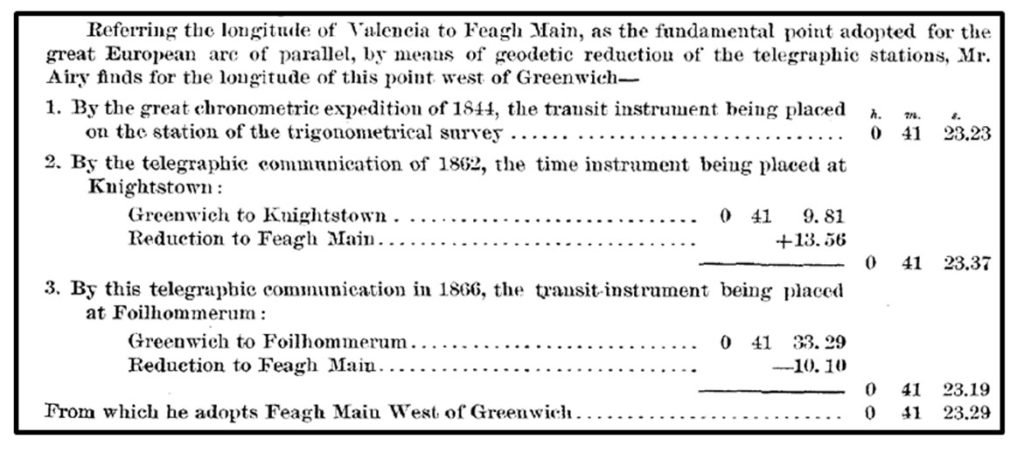

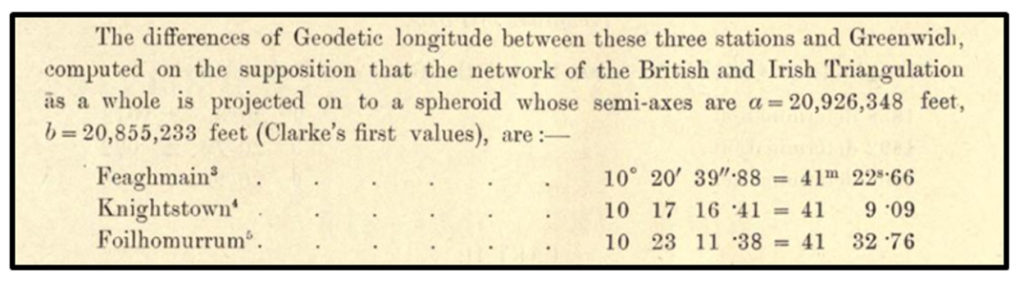

In 1866, astronomical longitude was determined at Foilhomurrum by officers of the United States Coast Guard Survey.[5] It had been determined at Feaghmaan (near Chapeltown) in 1844, and at Knightstown in 1862.

For the project of 1866, a temporary observatory was erected near the telegraph station at Foilhomurrum. It was protected by rising ground on the northwest and was bolted to large stones in the ground. The piers were of stone.[6] The observers there were eminent astronomers, Dr Benjamin Apthorp Gould (1824-1896), author of The family of Zaccheus Gould of Topsfield (1895)[7] and Alonzo Tyler Mosman (1835-1913), after whom, in 1879, the Mosman Inlet in Etolin Island, Alaska, was named.[8]

Return Trip

‘Valencia – Heart’s Content – the only determinations of longitude will be by comparisons of clocks between the stations’

Alonzo Tyler Mosman returned to Valencia the following year, 1867.[9] On this occasion, he was in company with Professor Benjamin Peirce (1809-1880), Superintendent, United States Coast Survey. Professor Peirce described the event:

On the 1st October I met Mr Mosman at Killarney. According to previous arrangement he had already brought the instruments to that point by rail, and had visited Valencia to examine the ground and learn what provision would be required for the stone piers of our transit instrument and clock, and for the materials of our astronomical station. From his report it was manifest that the requisite supplies could be obtained upon the island, or in its immediate vicinity, and early on the morning of October 2 we started westward. The six large boxes of instruments were piled and carefully made fast upon a large ‘Irish car’ the only vehicle upon springs to be found in the town, and the transportation of this huge tower on wheels forty-two miles to the ferry across the Straits of Valencia, and deposit of the instruments in a place of shelter, were accomplished without accident before daylight had wholly disappeared.

The object of their expedition was to calculate the longitude difference between Greenwich Meridian and Harvard College Observatory.[10] It was anticipated that their work would be conducted at Knightstown, but for a number of reasons, this proved impractical.[11]

It was therefore decided to erect a more substantial observatory at Foilhomurrum, a place described as ‘remote from any other dwelling-house except the unattractive cabins of the peasantry’:

Here, as close to the telegraph-house as was consistent with an unobstructed meridian, the astronomical station was established, and a building constructed eleven feet wide and twenty-three feet in length. This was divided by a transverse partition into two apartments; the larger of these serving as an observatory, while the eastern end was used as a dwelling place. This building was bolted to six heavy stones buried in the earth, and was protected from the southwest gales by the telegraph-house, the corner of which was within a very few yards at the nearest point; while rising ground to the northwest guarded us against the winds from that quarter.

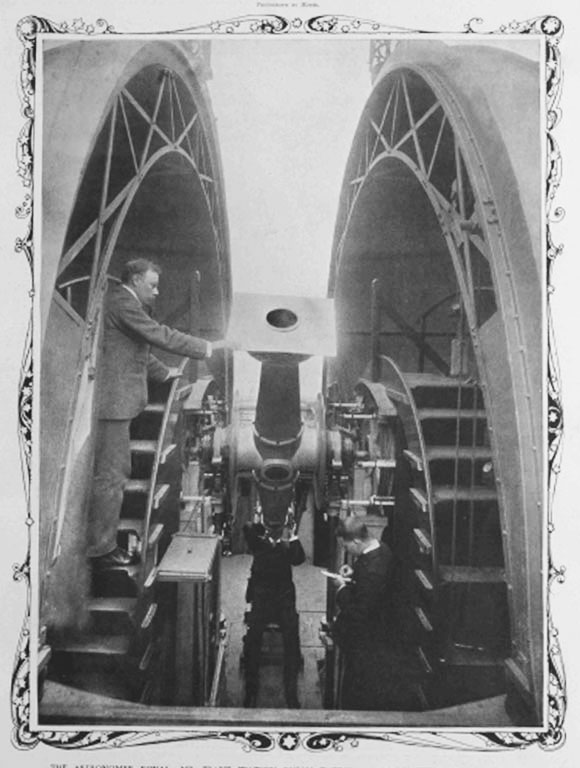

In the observing-room, the transit instrument, clock, and chronograph were mounted. It also contained a table for a relay magnet and Morse register, and a recording table.[12]

Professor Peirce remarked on the wonderful Kerry welcome they had received at Valencia:

For the kind reception which we met at Valencia, I know not how to give an adequate expression of my thanks. A more hearty welcome, a more thorough and delightful hospitality, or more friendly aid, could not have been found at no time or place. The inevitable hardships and exposure of our life, at a distance from any permanent habitation other than the over-tenanted house of the telegraph company, and under circumstances apparently incompatible with comfort, were thus mitigated and compensated to an incredible degree.

The visiting astronomers also extended thanks to the resident landlord:

To the Knight of Kerry we were indebted, not only for a hospitality worthy the traditional reputation of the land, and for which we shall always remain personally grateful, but also for the most practical and efficient aid in furtherance of our operations. All his agents received instructions to assist us by every means in their power; his buildings afforded storage for our instruments at Knightstown; his quarries and stone-cutters furnished piers; his factor enabled us to obtain lumber; and his carpenter was detailed for expediting the work upon our building.

Gratitude was further extended to ‘the gentlemen of the telegraphic staff’– their neighbours in the telegraph field, who had welcomed them into their accommodation and shared their comforts:

Of the sixteen electricians and operators in the service of four different companies, there is no one to whom we are not indebted for essential aid in our work, as well as under personal obligations for many acts of kindness. To James Graves Esq, superintendent of the station, and Edgar George Esq, second in charge, we owe especial acknowledgments.

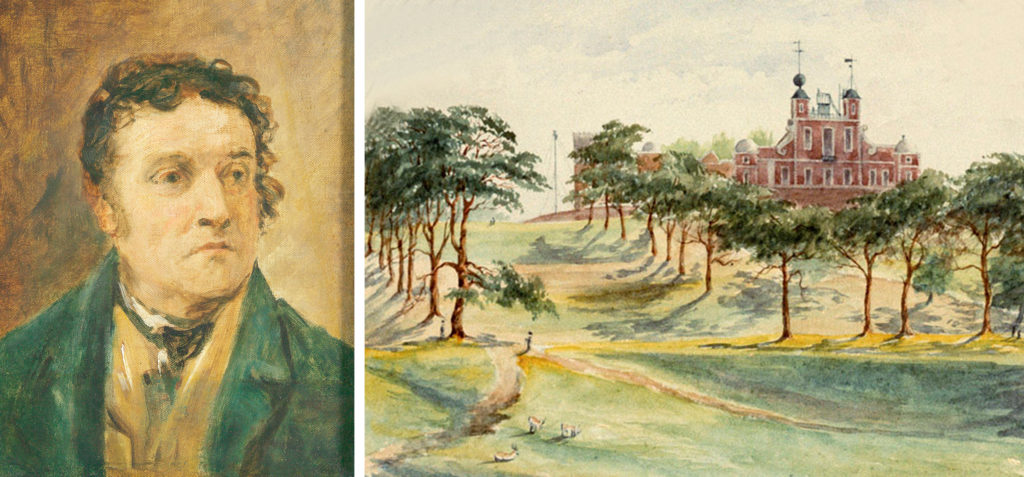

Sir George Biddell Airy

The Astronomer Royal, Sir George Biddell Airy (1801-1892), also played a vital behind-the-scenes role in events of 1867. He fully supported the undertaking and, when it transpired that the station had to be located at Foilhomurrum, he agreed to carry out a third determination of longitude between Greenwich and Foilhomurrum.[13]

Sir George Biddell Airy was no stranger to Valencia. He had commanded the expedition to the island in 1844.[14]

Expedition of 1844

In 1844, longitude had been determined by chronometers on the hill of Geokaun in the townland of Feaghmaan West, more or less in the centre of the island:

Mr Airy agreed to complete the great arc of parallel, extending from the Oural river in Eastern Europe, by an accurate determination of the difference of longitude between Greenwich and Valencia. This operation was performed by the transmission of thirty pocket chronometers backwards and forwards, eight times each way between Greenwich and a temporary observatory at Kingstown, and ten times each way between Kingstown and a temporary observatory on the hill Geokaun near the centre of the island of Valencia.[15]

An account of this expedition reads today like an adventure story. The first task had been to decide on mode of transport from England to Ireland.[16] ‘Consideration had to be given to land and rail travel and frequency and regularity of steam boats.’[17]

Although the Bristol to Cork, to Killarney, and Valencia, route appeared most suitable, the Liverpool to Kingstown, to Dublin, Limerick, Tralee and Valencia, was ultimately adopted. Sir Airy wrote:

I had proposed to carry the chronometers through the whole length of the line from Greenwich to Valentia but… it was decided to divide the arc into two parts … the general plan of conveyance was the construction of a great number of strong boxes … Arrangements had been made with Mr Bianconi for the supply of a car with four relays of horses for the conveyance of the cases in a box, wedged firmly by straw mats in the car-box, between Tralee and the Cahirsaveen ferry. They were accompanied by a private soldier.

The party arrived at Caherciveen during the night and special arrangements had to be made for a boat to cross to Valencia Island:

On my application to Captain Hornby RN Inspector of the Coast Guard, and Sir James Dombrain, Inspector of the Coast Guard for Ireland, instructions were given to Mr Quadling, the officer in charge of the force on the Cahirsaveen and Valentia station, to place a boat and the necessary party of men at my command.

Barnabus Edward Quadling of the Coast Guards duly carried out his instructions.[18] On arrival at Valencia, it was a three mile journey to the station of Feagh Maan, and ‘the large box was carried by two men by means of two poles fixed in staples in the manner of a sedan-chair.’ Despite not the best of roads, ‘the chronometers were carried perfectly well.’

The transit-station at Valencia and pier had been built by Lieutenant Hornby in 1843 at the request of Sir Airy, ‘It was necessary to adopt a position somewhat south of the survey-station in order to command the low ground of the Island, on which it was proposed to plant the meridian mark.’ The observatory was a panelled hut covered with canvas:

The transit-piers were formed of blocks of slate from Valentia quarries … the meridian mark was a plate of metal fixed upon a large block of stone, guarded by a private of the Royal Sappers and Miners.[19]

Expedition of 1862

Sir George Biddell Airy also directed the expedition to Valencia of 1862. The expedition was suggested by M Struve and Sir Airy wished to cooperate with him ‘in establishing an Arc of Parallel from Valencia in the West to Orsk, on the river Oural, in the East.’[20] Sir Airy wrote, ‘The repetition of the measure of astronomical longitude between Greenwich and Valencia can be no longer delayed.’[21]

On this occasion, he did not travel to Valencia but sent two assistants of the Royal Observatory to undertake the work, Edwin Dunkin (1821-1898), chief observer, and George Strickland Criswick (1836-1916).[22]

The event was reported in the local press:

A party of the Royal Engineers under the command of Captain Clarke arrived in Valencia last week in the schooner Pilgrim for the purpose of correcting an error in the longitude of Valencia. They have fixed their station on the hill above Knightstown and have erected huts to live in during their stay which will be about seven or eight months.[23]

A description of the work to be done, in layman’s terms, was also given:

The error, which is supposed to be about 400 feet between the longitude as determined by observation and that obtained by actual measurement, is attributable either to a difference in time between the chronometers used in the survey – this might have easily occurred for though a constant stream of chronometers was passing between Greenwich and Valentia during the survey, a slight difference between their times was quite possible; or the err is due to local attraction. If the error was owing to the first cause, the present arrangements will soon correct it – a wire extends from the telegraph office in Knightstown to the observatory on the hill, which will put the observers in immediate and direct communication with Greenwich. The moment the ball falls in Greenwich it will be indicated at Valentia. If the error is found not to result from a difference in time it must be owing to local attraction.

The importance of correcting the error was explained:

The importance of ascertaining the existence of and correcting this apparently trifling error will be obvious when it is considered that Valentia is the terminal station of that grand triangulation which, beginning from the Ural mountains, is closed at Valentia. This line is the longest land area of a great circle in the globe. The survey has been carried on for many years by the governments of Russia, Prussia, France and England and this experiment at Valentia will close this great effort of science and of long years of patient watching and observation. Three clear days will be necessary for making the observations, but as they will have to be tested in various ways, principally by observations of certain stars, the period of the stay of the Royal Engineers will, it is supposed, extend to seven or eight months.

Royal Engineers Sir Henry James (1803-1877) and Alexander Ross Clarke (1828-1914) loaned an observing hut and the Knight of Kerry and Robert John Lecky (1809-1897) contributed to all local aid required.[24] A 12-inch Altazimuth by Simms, on loan from T Coventry Esq, was used for the work.[25]

Dunkin wrote of their excursion:

Our daily rambles about the island gave us much enjoyment. Some of the charming views over Valencia harbour forcibly reminded me of the scenery in the Upper part of Christiania Fiord near the city [Oslo, Norway]. One favourite landscape was seen from the back of Glanleam, the island residence of the Knight of Kerry … a picture no artist could depict with one half of the beauty that it deserves.[26]

The work of Mr Criswick and Mr Dunkin, who remained at Valencia from 11 June to 23 July 1862, culminated in the laying of an Altazimuth Stone at the site.[27]

Later in the year, Sir Airy published a report of events at Valencia.[28] An abstract of his findings was also published.[29] It concluded that ‘implicit confidence may be placed in the old determinations for Liverpool and Knightstown’[30]

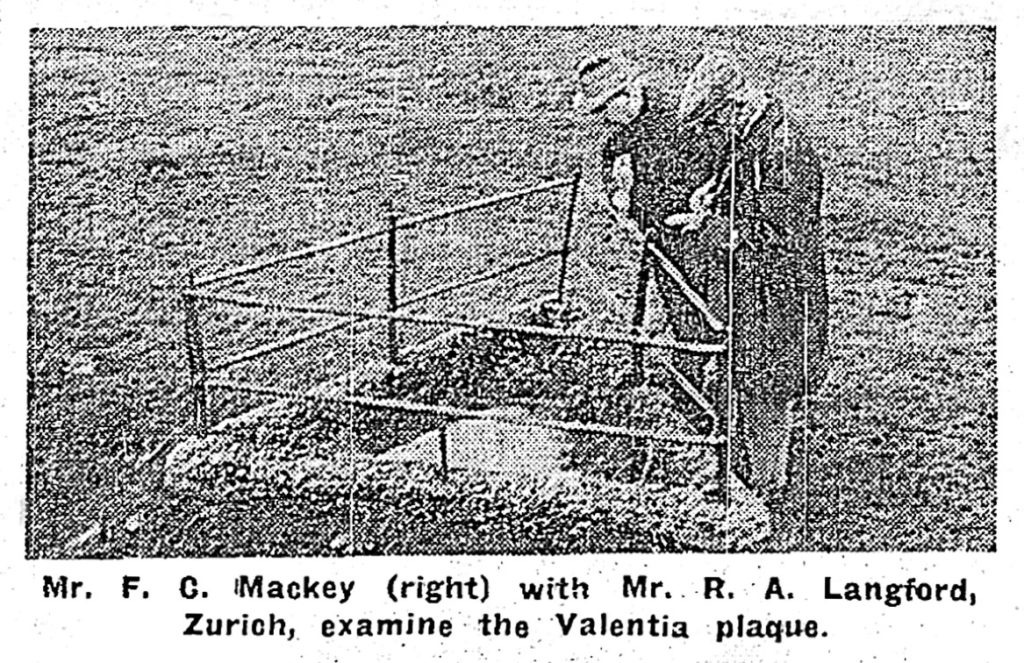

Commemorating the Past

In the year 2000, Valentia Tidy Towns unveiled a replica of the by then damaged Altazimuth stone, sculpted by Alan Ryan Hall.[31] It is inscribed, ‘Great European Arc of Longitude, site of the position of the Altazimuth used in the determination of the longitude of Valentia in 1862.’[32]

An information board at the site records the following:

The quest for a solution to the longitude problem occupied scientists and their patrons for the better part of two centuries. In 1714 the UK Parliament offered a King’s ransom (£20,000) to anyone whose method of device proved successful. Astronomy, navigation and clockmaking were all used in the process and this is where the Knightstown, Altazamuth Stones comes good. An Altazamuth is a Theodolite-type instrument used to determine the lines of Longitude. In all the scientific and other methods used to determine Longitude, two Altazamuth readings were taken – One in the village of Knightstown, Valentia Island, and the other in the Ural Mountains in Russia. On completion of the readings, an Altazamuth Stone was placed at the appropriate spot. The ‘replica’ stone here before you marks the area of the site of the Altazamuth. Its significance in safe navigation and the saving of lives at sea in unquantifiable. It is indeed of national and international importance. We thank all concerned who helped in any way with this Altazamuth project, which was instigated and supervised by Knightstown Tidy Towns. All those people, will, I’m sure, forgive us for mentioning one person who helped and would be proud of this project, namely P J O’Sullivan, RIP, former Parish Priest of Valentia Island. Knightstown Tidy Towns 2000.[33]

_____________________

[1] Junior Browne, otherwise Cornelius Joseph Browne, of the long established manufacturers in the town, passed away in August 2019. See ‘Foilhomurrum: Its Position in History’ (IE MOD/71) on the O’Donohoe website for further reference to the Foilhomurrum area. [2] See ‘Glory to God: Castleisland’s Link to the Atlantic Telegraph’ (IE MOD/71) on the O’Donohoe website for further reference. Peter Browne has donated a number of documents relating to the field to the O’Donohoe Collection, reference number IE MOD/C72. [3] Leeds Times, 11 August 1866. ‘It will no longer suffice to indicate a date, and say, ‘Such a day, such an hour;’ it will be necessary to add, ‘time at such a place.’ Thus the clerks of the new telegraph office take care to add to the communication exchanged between the two continents the express mention: time at Paris, or Greenwich, or New York, or Washington.’ [4] Waterford News, 31 August 1866. To make his point, Msr Babinet exhibited a thick cable which had been five years under the channel: ‘The external metallic coating peeled off in shreds. The salts of the water corroded the metal and got to the central wires. The water eats away a millimetre of metal per year and what wire could withstand such waste? Yet the Channel cable was thick andn the Atlantic one is thin. I have good reason for believing that the success of the cable this time is only ephemeral. The communications will not be of long duration. We should, therefore, turn it to good account, and as in the first attempt £720,000 were uselessly spent, and £760,000 have been laid out on the new cable, we should at least ascertain the exact longitude of the American station. General Morin: A longitude which would cost £760,000 is dear. The shareholders of the company will certainly be of my opinion (laughter). M Babinet: It will be a small dividend indeed but it is better than nothing (renewed laughter)’ (Waterford News, 31 August 1866. [5] Telegraphic Determinations of Longitude made in the years 1888 to 1902 (1906) Sir William H M Christie, Astronomer Royal, Part II, vi & vii. ‘It was thought desirable that as a supplement to the determinations of the longitudes of Valentia and Waterville the longitude of a third station in the neighbourhood of the Western end of the Great European arc of longitude should be determined as a check on possible local attraction at those places. The principal station of the Ordnance Survey at the Western end of the European arc is at Feaghmain in the north-west of the island of Valentia. The astronomical longitude of this place was found in 1844 by transmission of chronometers to be 41 m 23 8 '23 6 west of Greenwich (Bradley's Meridian). The longitude of Knightstown in the north-east of Valentia island was determined by telegraphic communication in 1862 …. The astronomical longitude of a third station, Foilhomurrum, in the south of the island, was found in the course of the work of the trans-Atlantic longitude determination made in I866 by officers of the U.S. Coast Survey.’ [6] U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (1925), p278. [7] Benjamin Apthorp Gould’s family details are given on pp200-201. His son, Benjamin Apthorp Gould (1870-1937) would appear to be the author of War Thoughts of an Optimist (1915) and The Greater Tragedy and Other Things (1916). [8] Islands of County Kerry: Valentia Island, Blasket Islands, Skellig Islands, Innisfallen Island, Magharee Islands, Puffin Island, Kerry (2010) Books LLC: ‘Prior to the transatlantic telegraph, American longitude measurements had a 2,800-foot (850 m) uncertainty with respect to European longitudes. Because of the importance of accurate longitudes to safe navigation, the U.S. Coast Survey mounted a longitude expedition in 1866 to link longitudes in the United States accurately to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Benjamin Gould and his partner A. T. Mosman reached Valentia on 2 October 1866. They built a temporary longitude observatory beside the Foilhommerum Cable Station to support synchronized longitude observations with Heart's Content, Newfoundland. After many rainy and cloudy days, the first transatlantic longitude signals were exchanged between Foilhommerum and Heart's Content on October 24, 1866.’ [9] ‘Messrs Davidson and Dean left Boston for Halifax, in the steamer of September 5, to make an examination of the condition of the telegraph line and a week later Messrs Goodfellow, Mosman, and myself sailed in the Cunard steamship Asia bound for Liverpool via Halifax and Queenstown, taking the instruments for Newfoundland and Ireland. But a short time before our departure, the welcome tidings had arrived of the recovery in mid-ocean of the lost cable of 1865, and of the successful continuation of this second line to Newfoundland … On the morning of Saturday September 22 the Asia arrived off Queenstown, where Mr Mosman landed with the instruments, while I kept on the voyage to Liverpool and thence to London to confer with the officers of the company. The management and control of the cables being with the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, which had conducted the expedition of 1866, and not with the Atlantic Telegraph Company, on whose friendly promises of assistance we had depended, it became necessary to apply anew for permission to use the lines, and for the needful facilities at Valencia. To the cordial friendliness of George Saward Esq, secretary of the Atlantic Company, we had already been indebted for many acts of courtesy, and he aided me without delay in the most effective manner. The use of the cables was at once granted by John C Deane Esq, secretary of the Anglo-American Company … and I was furnished by him with letter to the telegraphic staff at Valencia. From the eminent electrician to the company, Latimer Clark Esq, I received much valuable information and important practical suggestions, as well as full authority for the trial of electro-magnets in connection with the cables, beside the needle-galvanometers in use by the company’ (Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey 1867 (1869) by Professor Benjamin Peirce, Superintendent, Unites States Coast Survey, pp1-335 with preface ppI-XII. Conducted ‘during the surveying year, from November 1, 1866, to November 1, 1867.’ III. History of the Expedition, pp60-67). [10] As recorded on a plaque at Foilhomurrum: In 1867, the US Coast Guard Survey established Foilhommerum Longitude Observatory beside the Cable Station. Using a telescope and astronomical clock connected via the telegraph cable, star passage times were observed for the purpose of calculating the longitude difference between Greenwich Meridian and Harvard College Observatory. [11] Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey 1867 (1869) by Professor Benjamin Peirce, Superintendent, Unites States Coast Survey, pp1-335 with preface ppI-XII. III. History of the Expedition, pp60-67). ‘The longitude station occupied by Mr Airy in the great chronometer expedition of 1844 was at Feagh Main, an elevated position previously used as a station by the British Trigonometrical Survey; his transit instrument being placed upon the station-point. For the telegraphic determination of 1862, the instrument used for determining time was mounted in the village of Knightstown, at the eastern extremity of the island. The employment of the same station-point, the position of which was well marked, was of course highly desirable. Moreover, it was situated at that point of the island which afforded by far the greatest conveniences, and it was close to the hotel. But the electricians of the company have always been extremely averse to any connection, however brief, between the cable and any land lines, on account of the possibility of injury to the cable by lightning. This fact, to say nothing of others connected with prompt exchange of messages with Newfoundland, and a readiness to avail ourselves of any sudden change of weather at either place, rendered it imperative that our station should be established very near the building of the telegraph company at Foilhommerum Bay, five and one-half miles west of Knightstown, and remote from any other dwelling-house except the unattractive cabins of the peasantry.’ [12] Nothing remains of the observatory, nor can any information be found about its subsequent history. [13] ‘His own plans had been formed, authority obtained, and some of the preparations already commenced for making a telegraphic longitude determination between Valencia and Newfoundland in June next; but with extreme kindness he placed me in possession of all his special information pertaining to the subject, and aided our operations with word and deed…. Subsequently, when, to my own great regret as well as to his, it proved necessary to establish our station at the cable terminus, near the western end of the Island of Valencia, rather than at either of the two points for which he had already determined the longitude from Greenwich, he carried out a third determination of longitude for Valencia, by a telegraphic interchange of signals between Greenwich and our station at Foilhommerum Bay’ (Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey 1867 (1869) by Professor Benjamin Peirce, Superintendent, Unites States Coast Survey, pp1-335 with preface ppI-XII. Conducted ‘during the surveying year, from November 1, 1866, to November 1, 1867.’ III. History of the Expedition, pp60-67). ‘It has already been stated that the astronomer royal cordially acceded to my request that he would take measures for the determination of the longitude between Greenwich and our station at Foilhommerum. This request was made with diffidence, since Mr Airy had already determined the longitude of two other points in Valencia with all possible care, Feagh Main, the highest point on the island having been measured chronometrically in 1844, and Knightstown telegraphically in 1862, so that the establishment of our station at Foilhommerum implied the determination of an additional arc in order to connect it with Greenwich, whereas we had hoped to adopt the old station of the astronomer royal at Knightstown, six miles to the eastward … Exchanges were attempted on ten nights between the 3rd and 15th November but were successful only on the 5th, 13th, and 14th,’ ibid, p114. [14] In 1844, operations occupied nearly the whole time from the end of June to end of September. [15] ‘The numerous observations and chronometer comparisons were exhaustively discussed by Mr Airy and the resulting difference of longitude between the Royal Observatory and Valencia was obtained with great exactness. This accuracy was afterwards confirmed by two independent determinations, made in 1862 and 1866, by the transmission of galvanic signals from one station to the other, as may be seen by the three separate resulting differences of longitude for the station of the Atlantic telegraph cable at Foilhommerum Bay, Valencia, determined from the observations made in 1844, 1862, and 1866’ (Obituary to Sir George Biddell Airy KCB in The Observatory (1892), Vol 15, pp74-94). [16] The routes discussed were Bristol to Cork and then to Killarney and Valencia; Pembroke to Waterford and then to Killarney and Valencia; Holyhead to Kingstown and then to Dublin, Limerick, Tralee and Valencia; Liverpool to Kingstown and then Dublin, Limerick, Tralee and Valencia. [17] Greenwich Astronomical Observations (1845) ‘Determination of the Longitude of Valentia by transmission of Chronometers’. This essay, which formed an appendix, was published a few years later under title, Determination of the Longitude of Valentia in Ireland by Transmission of Chronometers (1847) by Sir George Biddell Airy (1801-1892). [18] Barnabus Edward Quadling Esq, RN, Inspecting Officer of Coast Guards, Achill, died on 27 September 1856 aged 65. ‘He served 54 years, having entered the navy in 1803 at the age of 11. He was present at the battle of Trafalgar in the Hydra, Captain (now Admiral) Munday, and took part in many of the brilliant engagements under Lord Cochrane during the war for which he received the war medal’ (Armagh Guardian, 10 October 1856). [19] Greenwich Astronomical Observations (1845) ‘Determination of the Longitude of Valentia by transmission of Chronometers’. ‘In mounting the transit and erecting the observatory and neighbouring huts, in fixing the meridian mark, and, indeed, in every operation connected with the island of Valentia, the greatest assistance was given with the utmost kindness by the Knight of Kerry and by Bewicke Blackburn Esq, the principal residents on the island.’ [20] ‘At the recent visitation of the Royal Observatory, Mr Airy availed himself of the opportunity to inform the Board of Visitors, that he has ascertained that M Struve is desirous that the following suggestions should be carried into effect, as regards the proceedings in the British Survey, for exhibiting the comparison of measure with theory in one of more extensive arcs of parallel: 1. That the junction between the British and the French or Belgian triangles should if necessary be repeated. 2. That a new determination of the longitude of Valentia by the galvanic telegraph might be recommended, especially as on the former occasion personal equations were determined only at the end of the operations, and observers were not interchanged’ (Freemasons Magazine and Masonic Mirror, 16 June 1860, p472). ‘[It was] decided on repeating the determination by galvanic signals. The principal motive for this was, the desire of co-operating with M Struve in establishing an Arc of Parallel from Valencia in the West to Orsk, on the river Oural, in the East.’ See note 29 for reference. The name Struve relates to astronomers (father and son) Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve (1793-1864) and Otto Wilhelm von Struve (1819-1905). In this instance, the reference appears to be to the former: ‘The great arc of parallel, extending from the Ural mountains in Eastern Russia to the westernmost point in Ireland was in 1862 nearly completed. So far as the differences of longitude of the intermediate stations were concerned, this great undertaking had been carried on under the guidance of Professor F G W Struve of Pulkowa, by whom all the arrangements of the continental observations had been planned. In 1844, the difference of longitude between Greenwich and Altona was determined, in connection with Professor Struve’s operations, by the transmission to and fro of a number of chronometers’ (Autobiography of Edwin Dunkin, Michael O’Donohoe Collection Reference IE MOD/71). [21] Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy (1896) Edited by Wilfrid Airy. ‘I have alluded, in the two last Reports, to the steps necessary, on the English side, for completing the great Arc of Parallel from Valencia to the Volga. The Russian portion of the work is far advanced, and will be finished (it is understood) in the coming summer. It appeared to me therefore that the repetition of the measure of astronomical longitude between Greenwich and Valencia could be no longer delayed. Two Assistants of the Royal Observatory (Mr Dunkin and Mr Criswick) will at once proceed to Valencia, for the determination of local time and the management of galvanic signals.' [22] George Strickland (or Stickland) Criswick: Mr Criswick served as assistant at the Royal Observatory Greenwich for 41 years, retiring in 1896. He was a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1868 and a Member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. He married Elise Tudor Hassall (1846–1919). He died on 26 January 1916. Further reference, see biography, http://www.royalobservatorygreenwich.org/articles.php?article=1107 Edwin Dunkin: Served at the Royal Observatory Greenwich for 46 years; one of the founders of the British Astronomical Association for which he served as secretary, president and vice-president. Dunkin wrote of the 1862 expedition: ‘The excellent resulting value deduced from this expedition [1844] would probably have been accepted as final if the new galvanic method of recording transits had not been brought into daily use at the observatory’. He also notes, ‘A popular account of this visit to Valencia in 1862 was written by me on my return. It is published in the Leisure Hour for 1863, under the title of ‘West of Killarney.’ A number of his contributions to the Leisure Hour were subsequently published under title The Midnight Sky: Familiar Notes on the Stars and Planets (1869), which caused Carlyle to exclaim, ‘O why did not somebody teach me the stars!’ Dunkin married and had children. He died on 26 November 1898 and was buried in Charlton cemetery. Further reference, see biography, http://www.royalobservatorygreenwich.org/articles.php?article=1117. Note: The unpublished autobiography of Edwin Dunkin, 1894, from which the above quotations are taken, was discovered in a garage in Southend in 1970 and purchased by the Royal Astronomical Society. The original manuscript is held at the Public Record Office. It is held on microfilm at the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives, ref: RGO 35/183. Pages 236-244 are relevant to his expedition to Valencia. See also A Far off Vision. A Cornishman at Greenwich Observatory. Edwin Dunkin FRS FRAS 1821-1898 (1999) edited by P D Hingley and T C Daniel. [23] Kerry Star, 20 June 1862. [24] ‘One of the observing huts of the Ordnance Survey was placed at our disposal’ (from Autobiography of Edwin Dunkin, Michael O’Donohoe Collection Reference IE MOD/71). ‘Mr Criswick and I left Greenwich on the morning of June 9, 1862, and arrived at Dublin in the evening. Killarney was reached, by railway, on the following evening, in time for us to make a hasty visit to the renowned Lakes. The next morning we secured our places on the mail-car for Cahirciveen. This town is about three miles from Knightstown, on the island of Valencia. The journey between Killarney and Cahirciveen was a very enjoyable one, as the beautiful scenery of land and water was most enchanting especially the romantic beauty of Dingle Bay as seen from the main road on the Drung Hill. Here the road entwines itself around the sides of this precipitous hill, covered with heather form the base to the summit. Before us lay the beautiful bay of Dingle, of a most exquisite blue colour, and without a ripple, extending seven miles in a direct line from shore to shore, having as a background the noble range of mountains on the Dingle peninsula. Landing at Knightstown by the ordinary ferry-boat, we proceeded to our apartments at the Valencia Hotel, where we were duly expected in time for dinner. These apartments had been previously engaged for our use, in company with Captain (now Colonel) A R Clarke, RE, who was stationed at Valencia with a party of Sappers in business connected with the Ordnance Survey’ (ibid). ‘Our residence of six weeks in the island was made very agreeable by the hospitality of Mrs Fitzgerald, wife of the Knight of Kerry, who was at that time absent in England, and of Mr R J Lecky, the engineer and manager of the Valencia slate-works. I owe much to the kind advice and assistance of Mr Lecky, relating to the fixing of the foundation stone on which the altazimuth was mounted. This new foundation-block was substituted for that previously in use, on account of a suspicion of instability. Mr Lecky also made arrangements for insulating the instrument to prevent the effects of the ground tremors’ (ibid). [25] ‘The instrument used was an altazimuth of small dimensions. The circles were 12 inches in diameter, the length of the telescope 163/4 inches, and its clear aperture 1.8 inches’ (from Autobiography of Edwin Dunkin, Michael O’Donohoe Collection Reference IE MOD/71). ‘The route traversed by the signals, or galvanic current, was very indirect, passing through Cambridge, Doncaster, Sheffield, Liverpool, Carlisle, across the Irish Channel near Portpatrick, Belfast, Dublin, Mallow and Killarney. The length of the wire was 800 miles’ (ibid). [26] Ibid. [27] On their return journey, Mr Dunkin and Mr Criswick ‘remained one complete day at Killarney where we spent a few delightful hours in rambling over Ross Island and the shores of the Lower Lake’ (ibid). [28] ‘Determination of the Longitude of Valentia in Ireland by Galvanic Signals in the Summer of 1862’ by G B Airy Esq published as appendix III in Greenwich Astronomical Observations (1862). [29] Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 23, Issue 5, March 1863, pp164-166. [30] The article in full: ‘The Astronomer Royal adverts to the operation effected in 1844 for the determination of the longitude of the Feagh Main Station, in Valencia, by the transmission, ten times in both directions, of thirty pocket-chronometers, between Greenwich and Feagh Main; a transit instrument having been erected at Feagh Main, and the chronometers being compared with the transit-clocks at Greenwich and Feagh Main. Advantage was taken of the passage through Liverpool and Kingston to determine the longitudes of the Liverpool Observatory and of a station near Kingston Harbour. The longitudes then found were Liverpool Observatory, West of Greenwich 12 0’05/Kingstown Station, West of Greenwich 24 31’20/Feagh Main Station, West of Greenwich 41 23’23. For details, he refers to Mem. Roy. Ast. Soc., vol. xvi., or Greenwich Observations, 1845. After the completion of galvanic communication between London and Valencia (consequent on the laying down of the Atlantic Telegraph), and the connexion, through the agency of the London District Telegraph and the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph, between Greenwich and the London offices of the B and I M Telegraph Company, the Astronomer Royal, with the assured assistance of Sir Charles T Bright and E B Bright Esq (Engineer and Managing Officer of that Company), and of T B Moseley Esq, (their London Resident Officer), decided on repeating the determination by galvanic signals. The principal motive for this was, the desire of co-operating with M Struve in establishing an Arc of Parallel from Valencia in the West to Orsk, on the river Oural, in the East. The station now adopted was not that of Feagh Main, but a place in Knightstown, in the vicinity of the Telegraph Office. Sir Henry James and Captain Clarke, R.E., gave great assistance in the loan of observing hut, the conveyance of instruments, and other ways; and the Knight of Kerry and R J Leckie Esq contributed all the local aid that was required. It was determined that local time at Valencia should be found entirely by observation of zenith distances and a 12-inch Altazimuth (by Simms) was lent for this purpose by T Coventry Esq. The signals were simply movements of a galvanometer-needle at each station, the current being given at every 15 s nearly by an auxiliary clock. The observers, Mr Dunkin and Mr Criswick, remained at Valencia from June 11 to July 23. During this time there were few opportunities of star-observation in consequence of the continued bad weather, and few opportunities of observing galvanic signals in consequence of interruptions at the Telegraph Office of Mallow. On the whole, only six nights of effective signals with good determinations of local time were obtained. The Valencia observer throughout was Mr Dunkin, and the Greenwich observer of signals Mr Ellis. On reducing the altazimuth observations, great anomalies presented themselves in the determination both of latitude and of time. After carefully discussing the observations, and making some experiments at Greenwich, it became clear that the zenith-distances were always given too great by about 4”. The cause of this anomaly is not known. On applying the corresponding correction, the results were made harmonious. It is remarked, however, that very little depended on this correction, the observations having been well balanced on the East and West sides of the meridian. The signal-observations were then discussed nearly in the same way as in the determination of the longitude of Brussels (Mem. Roy. Ast. Soc., vol. xxiv.), and the results were the following: Time occupied in the passage of the current 0 0’129/Longitude of the Knightstown Station 41 9’81. By the kindness of Captain Clarke a geodetic connexion was made between the Feagh Main Station and the Knightstown Station, and their geodetic difference of longitude was found to be 13s 56. Applying this to the former determination for Feagh Main, it is found that the old operations would have given for Knightstown 41m 9s 67. The agreement of this with that found from the galvanic operation is very remarkable, and it proves that implicit confidence may be placed in the old determinations for Liverpool and Knightstown.’ [31] In conversation with Alan Ryan Hall, Valencia, 12 December 2019. The original stone, on private land, is located behind a wall a few yards from the newly positioned one. [32] ‘It is still there and is now on private property. It is weather beaten and the word ‘position’ has been hacked off. But under the guidance of Mr Egan and the Valentia Tidy Towns Committee at Knightsbridge a perfect replica has been made’ (‘Valentia recalls its longitude role’, Irish Times, 12 December 2000). [33] The spelling of Altazamuth is as given on the plaque; it is located in Altazamuth Walk, Knightstown.