I did not think that there was a juryman ever put a coat on his back would find me guilty

A reporter of the trial of John Twiss in 1895 made the following assessment of him from his speech from the dock:

He was an ignorant man in the sense that he got no education, and to him the powers of feigning feeling and putting it in emotional language was an entire impossibility. Had he been able to speak well grammatically and eloquently his words would not convey half the force or impressiveness, for their sincerity might then be questioned, but coming from a rude unfettered peasant the sentiments that he gave utterance to, the splendid courage with which he denounced his accusers, and the frenzied bursts of impassioned eloquence in which he asserted his innocence and defended his character, attest him to be a man of remarkable force of character, manful, self-reliant, and conscientious.[i]

Today, almost 125 years on, the words of John Twiss, printed below, echo with truth. His accusations against the prevailing legal system are clear and just. He understood the concept of law – ‘it is the policeman’s duty if he can to convict’ – but it did not equate with his experience – ‘I am not asking for anything but justice.’

In essence, his speech is his own defence. He did not just claim to be innocent but sought to show it. In a broader context, his speech is a startling indictment against the justice system which then prevailed, one which not only permitted the innocent to hang but contrived for it to happen.

This system is illustrated in the presentation to the powers that be of 40,000 signatures for the reprieve of John Twiss– a staggering figure and phenomenal achievement at the time – which was dismissed. As one writer put it:

It may not be out of place to state that 40,000 Irishmen, of every creed and class, petitioned John Morley for Twiss’s reprieve. But John Morley’s answer was a present of a hempen collar, which left a bluish gray mark on Twiss’ neck after death.[ii]

It is clear that in 1895, there was no legal recourse to prevent the execution of John Twiss of Cordal. Indeed, the law was his enemy.

Speech from the Dock

John Twiss, prisoner at the bar, you heretofore stood indicted for that you on the 21st day of April in the year of our Lord, 1894, feloniously, wilfully, and with malice aforethought, did kill and murder James Donovan against the peace and statute. To that indictment you pleaded you were not guilty, and for trial place yourself on God and your country. What have you now to say why sentence of death and execution should not now be passed against you.

John Twiss:

I am satisfied to die, for I am innocent, and the man who was brought up for the murder the jury discharged him, and now goes and brings me in for murder miles upon miles from the outrage, where it was committed, sleeping in my bed. And I should think that both, my Lord, should look into it, and the jury should look into their consciences, and not bring in an unfortunate man like me out of my bed in the county Kerry, which the other jury, brother gentlemen of them, did, and not bring in an innocent man guilty. I am satisfied to die, for I am not guilty and I am not ashamed of it, for I am not guilty of the charge. And I should think my Lord should take it into consideration, and take the evidence of a child between six and seven years old, and bring him to hang a man wrongfully, and bring me before a court of magistrates, and he could not identify me at first, and he identified me nine or ten days afterwards, and I think that the evidence for the alibis should be taken into consideration when the police were travelling from the town of Newmarket to the town of Castleisland, and there could not be a four-penny bit under their foot unknown to them. For nine or ten months they could find no evidence until they found one who was in for every thieving and stealing in Killarney, and who had been in jail fifteen times for giving me a revolver, a man that I never looked on. They have evidence brought up against me. They have a woman, Mrs Lyons, brought up. How can the jurymen believe it or the judge believe it. The woman that says she knows me for thirteen years, why should I go back and ask bread from her? Why I should expose myself? How could my Lord take it into consideration that I would be guilty of doing the like, or could any man do so. I am asking your Lordship to look into the case whether you consider my countenance guilty of that murder done in the county Cork. I am brought up, the other men are brought up, to put me instead of Keneally. They arrested Keeffe and brought in Keeffe. The gorsoon swore plump on Keeffe, and the jury in court discharged the man, and then I am brought up by bribery of the authorities but I am not a bit sorry for I am not guilty. I never saw the sky or clouds over the man. I say this, the jurymen should not bring me in through the evidence of a child or the evidence of alibis through the country, bribing them with money which you, my Lord, should take into consideration, and that you will also take into consideration that the tailor and his wife could not give second evidence. I should think that the same evidence should be correspondent. I should think you should look into the evidence. It is the policeman’s duty if he can to convict me, because they owed me spite for many a long year.[iii] It is very easy to handle pen and paper. You give them a statement and you will not know what he will write down. He will tell you to sign your name to it, and you will sign your name. You won’t know what he will write. He may write a statement for you, but he may not read it at all and then he may say you said such and such a thing. I ask you to look into it. I am not asking for anything but justice. I am not guilty. I was never guilty and I hope the Almighty God will account for me for I am innocent of this crime. The tailor’s wife saw me a hundred times. Her second evidence was never explained there before you at all. It was never brought up, and then there was the tailor himself. He was not sure that I was the man that was in the house at all, ‘I could not identify that man. I thought he was like him when I saw his name in the papers.’ She never said she gave me bread through the window. ‘I told my husband I gave him bread. I told him that was Twiss when the horseman went away.’ Now, a juryman there at present asked a question and says, ‘Did you say any remark to your wife after the horseman passing by. Did she make any remark to you.’ ‘No,’ says he. ‘My Lord, I ask you to take into consideration that question, and how could a jury rely on his wife after that false alibi swearing against me. I am asking justice, and I did not think that there was a juryman ever put a coat on his back would find me guilty. But they were suspecting me for years upon years for being a moonlighter – that is the whole cause of it. I was a moonlighter and I paid for it, but I never injured a man. I suffered in jail for it. I never robbed or killed a man or injured a man, but the policemen were down on me. If I brought the policemen up every time I caught them there, how would it look on paper. I caught two policemen, one of them having a goose and the other a duck. I caught them going to the hut, one of them was drunk, one of them was going over a fence, but I would hang before I would bring a dirty charge against them. I had a brace of greyhounds watching rabbits. The goose was alive, the duck was dead. One of the policemen was going on to a friend, and the moment he put his leg on the style the goose screeched, and he cut the head of the goose, and next morning I got the head of the goose there. A woman told me she was robbed last night by two bastards. ‘Who are they?’ says I, ‘The two Sullivans,’ says she. ‘Would it not be the police who may carry them?’ says I, and she said, ‘They would not do the like.’ If I got them two policemen arrested on that charge, how would it be on paper? I was brought up for being a moonlighter. I was a moonlighter and I suffered for it on two occasions. I was drunk on one of them. I never entered a house, and then for jurymen to bring me in on a brutal murder like this, and sure as God is in heaven the authorities know the man that killed the man. I swear I know the man that killed the man, and the police know the man that killed him, and they bring me up for the second man that killed that man. The police know who killed that man, but they would rather punish me than punish the man that killed him because they owes me spite. My God Almighty how could I leave my house at ten o’clock that night, when two policemen swore I was at home, and be sixteen or seventeen miles away and be on the scene of that murder? Where did I get the horse? Where did I meet the horse? Why was I not seen on the following day, brought up the following day by a bum-bailiff of Lord Ventry’s there as police minding him all his life. He fined me several times and is all his life fining me. How could Boyle and myself be friends, and he being a gamekeeper and he watching me.[iv] They took down his evidence, and believed his evidence. He was after shooting a respectable man and was in jail, and it was by the greatest work that Lord Ventry, a high gentleman of influence, brought him from being transported for shooting an innocent man. He was brought up four or five times for putting dirty mean charges on police. He shot one policeman. They stripped him of his arms and fined him £3. They never left him a policeman since. How is it the jurymen of Cork did not look into all these things? I am sure they saw the statements that were taken, and were then down before, and at the end of four months they are convicting an innocent man of brutal murder, committed on a bailiff in the county Cork, and I sixteen or seventeen miles away, and likely more. I should think it is a shame that a woman should come up in this fashion. What did she go and tell the priest for about the bread? Why did she not go and state to the gentlemen magistrates of the county Cork? Sure, she was not asked by the priest; what did the priest know about her seeing me? She was put up by the authority. Why did she come round? It was the authority that brought her round to identify me stronger, and bring me to the window that there would be no mistake in the way. I am not a bit changed in my countenance. I don’t give that much for it (snapping his fingers) because I am innocent and you will never see a man as innocent as I am of the charge and I will prove I am innocent of the charge, but by a wrong mistake of the jury they had no right to bring me in guilty of murder in the county of Cork on false evidence, alibi evidence through the country. The police have scoured the country from Newmarket to Castleisland, and all the time they have kept me in, but they could not find any evidence against me except Boyle, and they knew he was an enemy of mine. There were over two hundred houses from that place back to my house, and why did not a man, woman or child see me? I am not asking you anything. I am not asking you to free me from the gallows, but I am pleading innocent, and I am telling your Lordship and the gentlemen of Cork the conduct of the authorities coming in here to Cork half of them should be transported if the farmers from the country brought them up for their conduct. I caught two policemen in a most brutally conducted way. We were coursing in the parish of Brosna and I caught two policemen – one of them a sergeant – brutally drunk, and the other the same way, and they having a most charactered woman from the city of Tralee with them. They had her in a place called Raymond’s Groves, alongside the public road. If I brought them up how would that look. If certain parties turned on them as they turned on me – wrongfully, and bribed these alibis and corner boys through the country. I say, my Lord, myself and Keeffe were traced like greyhounds, up and down through the city of Cork and Newmarket for three or four weeks. They don’t have a lane in Cork that they don’t take me through, showing me to these characters and corner boys. They point me out to them, and then bring them before me, and say, ‘Did you ever see him before?’ and they would say, ‘I saw him before. I saw him in such and such a place.’ Well, now, my Lord, they brought a man to me in Cork, chief of the police. He came into Kanturk at the time I got the dose of poison at Newmarket. The sub inspector of police came into the hospital. I was sitting on a stool at the hospital door. He came up to me. ‘Well,’ he says, ‘that was a nice drive of poison Keeffe’s mother gave you.’ ‘The woman never did it to me,’ says I, ‘because I never saw her in my life.’ He said, ‘I am well aware now that it was she poisoned you before you would swear on her son.’ I said I could not swear on her son, because I never saw him in all his life. Here is the man; there he is (pointing to a district-inspector). He showed me likenesses and said, ‘Did you ever see them likenesses before.’ ‘I never did,’ said I. He pulled out seven likenesses, and says he, ‘If you take my advice you’ll never get an hour’s imprisonment.’ ‘What’s that,’ says I, ‘I don’t expect imprisonment, I’m not guilty.’ ‘There is so much evidence against you as will make you guilty, and there will be a packed jury in Cork as will never leave you out. I will,’ says he, ‘give you £50 if you bring in those six men. There are the Keneallys and there is Keeffe.’ When I told him, my Lord, that I never saw the men before, ‘If you don’t do that,’ says he, ‘I’ll have you managed by the woman.’ That is all I heard of the woman until I heard her swear here, and then says he, ‘The judge will believe the gorsoon, and will give inspiration to the jury as they will have to believe him that the gorsoon is swearing right on you that you are the man, and now he said by me and you will get yourself out, and you will not get twenty-four hours.’ I said, ‘I would never take any of your bribery money, there was never a man of mine took bribery money. I belong to the blood of gentlemen.’[v] He came in addition in Cork to me, and said, ‘Well, are you going to give me a statement.’ I said, ‘I had no statement to give him.’ ‘Well,’ says he, ‘If you give me a statement I will take it down.’ ‘I will give you no statement,’ says I, ‘because I was sleeping in my bed, and I know nothing about it.’ ‘Well, if you don’t,’ says he, ‘the rope – there is many inches around your neck, and if you don’t make a statement, I’ll manage you.’ There is the governor present, there is the gentleman who was present at that expression to me, a man, an unfortunate creature, to put him up for to hang innocent people through the country. It was the worst conducted thing for a policeman of his position to come into a prisoner while waiting for trial, and intimidate a man within an inch of his life that he would be hung. He didn’t care if I was damaging my soul so long as I did what he wanted me. I am asking you, my Lord, was it not a most frightful thing to come up and impose bribery money on me, and make an alibi and corner-boy of me. He had one picked up in Killarney and two in Castleisland, and I asked them why they did not bring up the man they brought into prison to me, and took me out of my sick bed. By God Almighty, such a case never came into court. There were two innocent men hanged here before – Poff and Barrett were hanged wrongfully by a jury in Cork. They were hanged wrongfully, and now they are hanging me, wrongfully, the third man up from Kerry. If I went to Wicklow or Tipperary, there is not a county in Ireland that a jury would convict me on the evidence that the present jury have convicted me on. I know you have known it in your heart that there is not a juror that ever wore a coat on his back that would convict me. I heard you address the jury fairable and honestable in my behalf and on the Crown behalf. I am thankful to you, my Lord. You never came against me in evidence because you knew the worth of the person who was swearing, whether they were right or wrong. The jurymen should know the same and be of the same opinion. I say this, there may be respectable men amongst the jury. I say it is a shame. Some of them may not want to convict me, but they may go with the brethren. The whole of the congregation here knows what I am saying is right. I am not asking any relief. I am ready to go to the gallows this minute because I am not guilty of the great murder but the conduct of the police and conduct of the jury –

Chief Baron Palles – I cannot allow you make any more reflections upon the conduct of the jury.

Well, it is a fright. Some of the jury would injure me, but more of them went by their brethren. It is a frightful case to hang me up for the murder of a Corkman’s doing and I would not be in this dock today. Then there is another man, Mr Rice, that could not prove honester than what he proved. He only proved to the shirt, and he saw no blood on it, but it is an old system of Murray’s when he makes for a man to put blood on his shirt. After the murder, and the hanging of Poff and Barrett, it should be an eye-opener to all the juries of Ireland to take a murder case into longer consideration than five minutes. It is a frightful thing to put the rope around a man’s neck. It would be a frightful thing if I took this bribery money and hanged innocent people. Death before dishonour. Hang me before you’ll hang a man. I am sure to die after a time. If I took that money, it won’t hold me long. I am just now sentenced by these gentlemen for death – by these gentlemen of the jury – and as God is my judge, I never saw the sky over his house. I never saw the gorsoon in my life. Is it not a frightful thing that all the evidence was not taken down before you? Because why? The Crown wanted to convict me. My blood is gone from them now, and I need not trouble them any more. They can take their ease now. I never struck one of them. I never saw one of them, and why in the world are they down on me to convict me of such a murder as this? Keeffe was brought in for that murder, and the child swore plump, ‘That is the man that murdered my father. The small man did nothing at all, but told him to come away.’ The two men who murdered the man – I am sure there are many men who know who murdered the man, and there are people in the court who know who they are, and that they are not in court here, but that they are around the country making their escape, and like Poff and Barrett, when I am dead and gone – I am no loss at all only to the young lady – then it will come out who killed the man. I won’t be six months, or maybe two months, buried when it will come out. ‘That man was hung wrongfully, that man was found guilty wrongfully. They are the two men who done it.’ These men might be walking around into the country chiefly when I am dead and buried for the murder of that man. This is the same turn up that was in Poff and Barrett. This is the same turn up as God is my judge. The two men that killed Poff and Barrett are over in the free land of America and whatever way they are over they cannot expect to be good or lucky for they were not gone three months when the name was mentioned. Poff and Barrett were found guilty of murder and hanged in Tralee. I am found guilty of the Newmarket murder and will be hanged in Cork but it don’t give me that much trouble (snapping his fingers) for I am not guilty of it. It is likely enough that misfortunate Keeffe was brought up the same way wrongfully by the authorities and the jury, of course, took it into consideration that the man was wrong but they never took me into consideration because I am a Kerryman. The police tried to break down the melt in me, they came in front of me dancing to break down the melt in me, but they could not break down the melt in me, because I am innocent, and said, ‘If there is only the evidence of a child of five years old against you,’ says one policeman, ‘a Cork jury won’t have a Kerryman do the like again – .’

The Chief Baron Palles – I won’t allow you to make any observations upon the jury. That is not permitted in the position in which you are at present.

I beg your pardon, my Lord.

Chief Baron Palles – Have you anything to say why I should not act upon the verdict?

I am not unfair with the jury, but what the police said –

Chief Baron Palles – Have you anything else to say?

A New Dawn

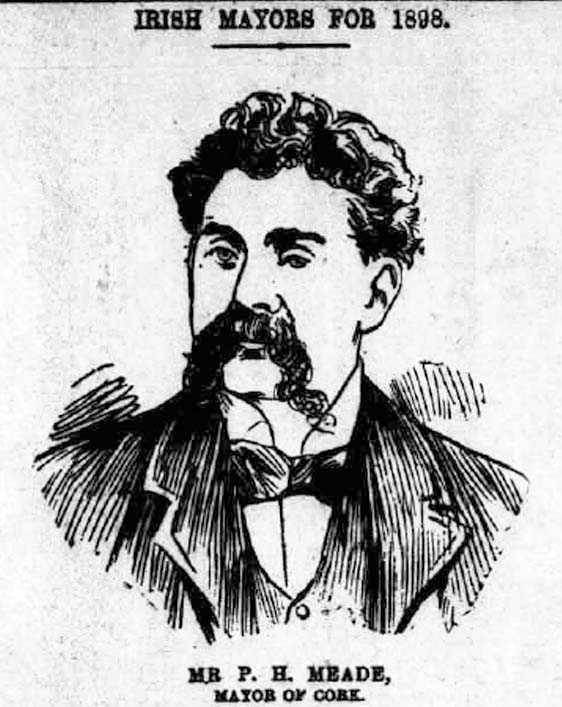

Twiss had little in the way of worldly goods to leave behind him. His faithful dog he left to the Mayor of Cork:

The men of Cork are having a collar made for that dog, with the following inscription on it: This greyhound was the faithful companion of John Twiss, who was murdered at Cork county jail on the 9th of February, 1895. Left by him as a souvenir to the mayor of Cork, P. H. Meade.[vi]

John Twiss’s true legacy is his speech from the dock, today a powerful instrument in the campaign to clear his name of murder. The Michael O’Donohoe Memorial Heritage Project has made application to the Irish government, on behalf of Twiss descendants, for the Presidential Pardon of John Twiss.

The project is also preparing application for the Presidential Pardons of Sylvester Poff and James Barrett.

____________________

[i] Flag of Ireland, 16 February 1895. [ii] The Boston Globe, 15 March 1895. The same writer remarked on Twiss’s gift of his greyhound to the Mayor of Cork, ‘Now, as one who is personally acquainted with the mayor of Cork, I make bold to state that he will feel more pride with John Twiss's greyhound walking by his side through the streets of his native city of Cork than he would in any honour that it is in the power of John Morley to bestow on him.’ [iii] It was stated in court in 1881 that ‘the constable of police in his district had no liking for John Twiss.’ [iv] It was said of John Twiss that he put many a rabbit on a poor widow’s table. Tipperary born Edward Boyle was gamekeeper and dog trainer at Cordal, on part of Lord Ventry’s estate, from at least 1869. He was known to be very strict in prosecuting his role and, over a period of more than 20 years, his name appeared regularly in court actions brought against poachers. He was consequently unpopular, was boycotted, and his life threatened several times. He was under police protection. [v] In this Twiss was perfectly correct. Burke’s genealogical records show that John Twiss traced his lineage to Richard Twiss of Killintierna, JP, agent to Herbert, Earl of Powis, who lived in the castle of Castleisland, the first of the family settled in Ireland at the close of the reign of Charles I. [vi] The Boston Globe, 15 March 1895.