‘We walk on their ground’

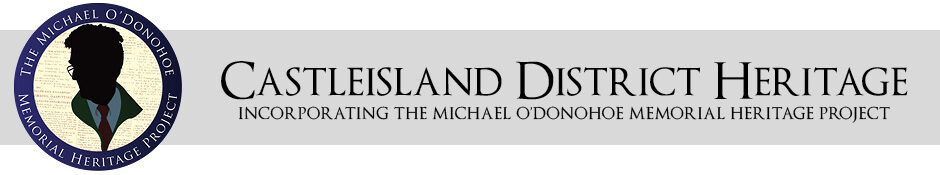

On 29 April 1892, the Casey family of Coolcurtoga, near Glenflesk, Co Kerry were evicted.[1] One hundred and thirty years on, the story of this family is told by Mary O’Donoghue of Coolcurtoga who lives and farms there with her husband Sean.

Mary, who is now a grandmother, researched the history of the townland in order to understand its local and social history. She learned that in 1852, a single tenant took over Coolcurtoga which ultimately led to her own occupancy:

The tenant came from across the Cork County boundaries … his four daughters were born and baptised locally … a daughter married and had six daughters here … in 1907, the eldest was matched to a local farmer’s son … their eldest son died a bachelor in 1978. He passed everything he owned to my husband.

Mary’s believes that because a single household has lived in or been in ownership of Coolcurtoga since 1852, a number of pre-Famine house ruins survive on the largely undisturbed land:

I have researched who lived in the little houses and found that every one of the dwellings was occupied through the Famine. I know who lived in each one from the early 1800s to the single tenant occupancy of 1852.

Mary is concerned that what remains of those tiny houses is protected for future generations as part of our heritage:

Our ancestors lived in those tiny houses. We walk on their ground. There were six of those houses here. This story is not about castles or the Lord of the Mansion of Sir Somebody. I’m speaking about the poor humble people who had no status either alive or dead who rest in the local cemetery in unmarked graves. I can say nothing, or I can tell their story.

This is Mary’s story.

Getting Started

I am a blow-in here. I was born in Tipperary. I was 46 years married on the 15th of November 2021 and have lived in Coolcurtoga since 1979. I’m not from a farming background but during the past 46 years I’ve grown to love this way of life. The Covid lockdown gave me an opportunity to finish a project that I left on the long finger since 2012. I felt I had to complete it and do my best with it.

I had already gathered data for Killaha parish and its townlands, I had the Tithe Applotment register of farm tenants here in 1833, I had the 1841-51 census which gave me the before and after Famine population numbers, I had Griffith’s Valuation.

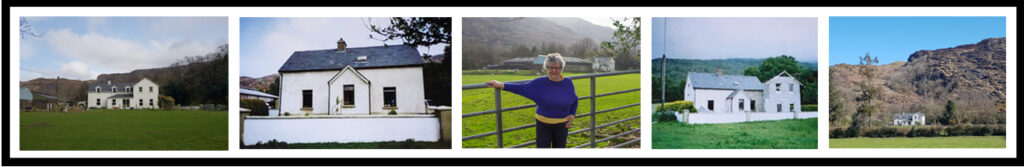

There were four tenant farmers here in 1833. At that time, it was part Coolcurtoga and part Incholouchra. In our time living here the name Incholouchra was never mentioned by anyone. It is a place that has vanished from living memory. In the Tithe records the two farmers for Coolcurtoga were John Murphy and Denis Healy. Between them they farmed 324 acres of mountain. The two farmers for Incholouchra were Daniel Healy and Roger Donoghue who had 530-2-0 acres between them. The combined acreage there was 854-2-2 acres which is larger than the acreage in Griffith’s Valuation of 761-3-34. However, 88 acres were adjusted in the Tithe records which brought the final figure to 768-2-0 acres. This is close to the figure of 761-3-34 acres in Griffith’s Valuation. It has been so ever since.

Coolcurtoga is a hill farm, not the Golden Vale. The mystery of there being two townlands in the Tithe records and just one in Griffith’s Valuation was only one of my stumbling blocks. What happened to the four tenant farmers named in the Tithe register? After some time I made some connections. I managed to locate (locally) the ancestors of the family of John Murphy of Coolcurtoga. I was not so fortunate with the Healy family. There are many by that name in the area and I found no way to positively identify if their ancestors lived in either Incholochra or Coolcurtoga. As for Roger Donoghue, I found that the maternal ancestry of a local family I know went back to him.[2]

In 1841 there were four houses occupied by twenty-two people. By 1852 there was only one house occupied, with six people living in it. What happened to the others? Did they relocate, emigrate, or die? It would be heart-breaking to think that sixteen people out of a total of twenty-two might have died of hunger.

In September 1848 (and into the early 1850s), an evaluation of the four little houses at Coolcurtoga was undertaken for the purpose of letting to new tenants, the records known as the House Books.[3] The landlord was Daniel Cronin Esq, The Park, Killarney, who later inherited Coltsman’s estates. His agent was Dan Courtayne, Killarney.

From these records I learned that in 1851 and some years before it, all four houses were occupied. In 1848, John Murphy’s house was occupied by John Burke; the house of Denis Healy (whose wife was Ellen Hegarty) was occupied by Dunn Healy (who had already been living here before 1848); Daniel Healy’s house was occupied by Daniel Sullivan and Roger Donoghue’s house was occupied by Daniel Reardon (or Riordan).[4] Daniel Reardon and John Burke had also entered into agriculture agreements as recorded in the Tenure Books.

By 1852 however, Griffith’s Valuation showed that Daniel Reardon was the only farm tenant here.

Daniel Reardon

Daniel Reardon had been living in the area for a number of years. The church baptism records show that his four daughters, Mary (1837), Elizabeth (1839), Johanna (1842) and Catherine (1846) were all baptised in the local parish church. The address given on the baptismal records was Knockanes. Daniel Reardon’s wife was Mary Dinneen. All four daughters married, into the families of Healy, Fitzgerald, Casey and Dineen.[5]

Daniel Reardon was said to be originally from County Cork. His great-grandson, Paddy O’Donoghue, who lived here before us, told Sean on a number of occasions that ‘a man came over from the County Cork and had four daughters.’ This was Daniel Reardon. I believe he may have originated in the Millstreet/Kilcorney area.

In 1852, Daniel Reardon took a 31-year lease of house offices and land (£30) on Coolcurtoga from Daniel Cronin Esq. He was an ambitious fellow because in the same year he also took a 31-year lease on Brewsterfield House from the Rev B Herbert (house, offices, gate-lodge and land 81-1-9 acres). He paid £50 for the land and £13.10.0 shillings for buildings. Daniel Reardon surely enjoyed the comfort of a big house with his wife Mary and their four daughters.

The Caseys

Johanna Reardon, third daughter, was to have Coolcurtoga. She married Daniel Casey from Killarney parish on 24 November 1870. They had seven children of whom six were daughters: Mary Hanora (30/1/1872), Margaret (31/8/1874), Elizabeth (16/5/1876), Johanna (18/8/1878), Mary Ann (7/12/1880) and Helen (15/3/1886). Their son John did not survive (28/4/1873 – 16/6/1873).

Daniel Reardon died about ten years after he took the 31 year lease. It’s fair to say that Johanna Reardon and her husband Daniel Casey followed on the 31 year lease in Coolcurtoga when it expired in 1883.[6]

There was much disruption during the 1880s with the Land War. Johanna and Daniel Casey were struggling to keep up with paying their rents on Coolcurtoga. The landlord, Daniel Cronin-Coltsman, had come to an agreement about building a house there around 1877. The house was built. However, the landlord reneged on promises he had made in regard to paying his share of the costs. This added to the Casey family burden and they fell behind in their payments.

On 29th April 1892, after much trouble, the landlord Daniel Cronin-Coltsman had the Casey family evicted. Their eldest daughter, Mary Hanora, was twenty years old and Helen, the youngest, was aged six years. A detailed report of the eviction, an extract from which is given below, shows the sorry state of things in those times:

A struggling but respectable tenant farmer on the property of Mr D C Coltsman JP (jnr) named Daniel Casey was evicted from his holding situate at Coolcurtoga (Glenflesk) for non-payment of rent. It would appear from the tenant’s statements that in consequence of his not being able to pay what he characterises an impossible rent, the relations between him and his landlord have been for a number of years estranged. He became tenant of the farm some twenty-one years ago having succeeded his father-in-law who was in possession of the place for a long time. The farm comprises about 5 acres of arable land with a mountain tract of about 800 acres. The arable portion of the holding is almost surrounded with a natural stream of water which in the locality is called a ‘cael.’ In wet weather, in consequence of the mountain streams flowing into it, this ‘cael’ becomes so swollen that the arable portion of Casey’s farm for a considerable part of the year is submerged … The tenant was all along asking his landlord for an abatement in his rent, and when the rents of the other tenants were being arranged out of court his rent was reduced to £35, which was still too high. He paid several sums from time to time, but when, in the month of June 1891, the agency passed from Mr J D Curtayne into the hands of Messrs Hussey and Townsend all hope of clemency was at an end. His cattle were seized and sold by public auction. His letter setting forth his grievances forwarded to the agents through Father O’Flaherty was answered with a writ, and finally his interest sold out by the sheriff at Tralee, and bought in by the landlord. The tenant’s family have been on the property for ever so long, and when he went to live at Coolcurtoga he had £550. After twenty-one years of toil and worry, he was, he says, evicted from the place without a penny. The Shrieval party, which consisted of two bailiffs from Tralee, and a representative of the agent’s named Spunner, arrived at the place at midday. They were protected by a small force of police from Killarney. When the house was reached the ‘brigade’ found the door barred against them. One of the bailiffs broke in the door and possession was taken without any further resistance. Casey has six children – all of whom are girls – and a wife. The second youngest of the children was sick and confined to bed with influenza. When the furniture was removed from the house one of the bailiffs approached the sick child with the object of disturbing it after his rough manner. He said the child was only ‘shamming’ whereupon the father protested and said he would cling to his child to the last, as he valued it more than Mr Coltsman’s whole property. A hand-to-hand encounter between Casey and the bailiff was arrested by the police by putting the latter out of the house. The sick child having been tenderly removed by its mother, the eviction was completely carried out. An emergency-man and two police were left in the house, while Casey and his family had to seek shelter from their neighbours for the present which was generously afforded to them.[7]

At some point after this, Daniel Casey went to America where he worked for a number of years. In living memory, Coolcurtoga was always known as ‘The Americans.’ Certainly the money to buy this place was American for as we shall see, Daniel Casey returned to Coolcurtoga.

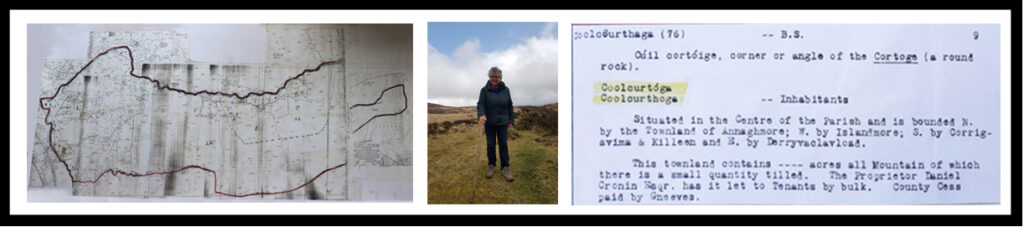

The Caretakers

During the period 1892-1899, John and Kate Rutherford lived at Coolcurtoga as caretakers. In 1892, during the land troubles, there had been a Police Protection Post here to protect those who inhabited evicted property.[8] The Rutherfords had at least three children, John (23/9/1893), Mary (born c1896) and Leslie (28/2/1897).[9]

John Rutherford senior died here on 12 February 1899 from a lung disease aged only 46. The address on his death certificate is Coolcurtoga, Headford, and his occupation was railway labourer. He left a widow Kate (née Phair) and three young children, John, Mary and Leslie aged seven and under.[10]

In the 1901 census, an O’Donoghue couple were living here as caretakers.[11]

Return of Daniel Casey

In the year 1906, after the passing of the Wyndham Land Act of 1903, Daniel Casey returned to Ireland. He quickly went about procedures to buy Coolcurtoga with his American money. It would seem that his daughter Hanora had gone with him to America for there is a very old travel trunk in our shed in remarkably good condition. It was Hanora’s trunk, brought back with her from the States. I believe some of her sisters may have stayed in America.

In June 1907, Hanora Casey married a local bachelor, Cornelius O’Donoghue of Coomacullen, son of a farming family. They were both in their mid to late 30s. Cornelius brought a dowry of £180 with him to the marriage. Shortly after the wedding, Hanora’s parents, now well into their 60s, transferred the farm which they had paid for into the name of Hanora’s husband Cornelius:

Transfer of Ownership: Cornelius Donoghue of Coolcurtoga, Glenflesk, County Kerry, farmer, is hereby registered as owner in fee simple of the lands above described and subject to the following additional burdens in favour of the said Daniel Casey and Hannah Casey, his wife viz: (a) Their right during their joint lives and that of the survivor during his or her life to be paid an annuity of eight pounds on the 1st of July, the first payment thereof was to have been made on the 1st of July 1908 (b) Their right to have the use of the room downstairs in the dwelling house on the said lands known as the parlour to be supplied with one quart of new milk and one quart of sour milk daily – six pecks of potatoes each.

Daniel and Johanna Casey were not in a position to restock the farm – this was the duty of their successors. The transfer naturally protected both Johanna and Daniel Casey until their deaths. Daniel died at Coolcurtoga on the 23 November 1917 aged 77. Johanna died on 27 April 1925 aged 83. They were buried at Muckross Abbey, their grave marked by a Celtic Cross.

My admiration, appreciation and respect for both of them is never ending. They were born pre-Famine. They could have walked away and cried. But they did not.

The Casey O’Donoghues

Hanora and Cornelius O’Donoghue had four children, Abbie (1908), Hanora Rita (1910-1962), Patrick (1912-1978) and Daniel (1913-1996). I was not able to trace Abbie so although I know she was born in 1908 I don’t know when she died. Hanora Rita was single when she died. She was always known as Rita, so maybe Abbie had another name too. She may have died very young. Patrick and his brother Daniel didn’t marry and there were no children.

After years and generations of good neighbours and friendships, eldest son Paddy O’Donoghue chose to will what he owned to Sean’s father, Jeremiah O’Donoghue (no relation). Jeremiah wasn’t able to accept it because of his late years. Paddy had already offered it to his younger brother Daniel who also did not want it at his time of life. So it was transferred to Jeremiah’s son Sean, my husband, then a young man. Paddy O’Donoghue died in 1978 aged 65.[12]

Sean O’Donoghue (booley)

When Sean was aged twelve, Paddy gave him a pet lamb. This was the beginning of Sean’s interest in sheep. He has farmed here for forty-three years. In 1975, we married. I will never forget how it felt to walk into this house for the first time in 1978/1979. One light-bulb in the kitchen end was my mod cons. No water. Flagged floor. Black beams crossing the kitchen. Black drips lined the floor underneath. A huge carpenter-made dresser with assorted colourful bowls and plates. A room called the parlour. A front porch opening towards the south west. Horse machinery parked here and there. A little pathway going through an old orchard of about a dozen trees. Clumps of wild daffodils grew here and there. A few clumps of lilies. The boundary was a line of mature native trees that shaded the house from the only sunlight it could have. To the right of the front view was a lean-to where Paddy stabled his horses. His horses and dogs were his companions. The stairs led from the big farm kitchen up the back wall of the house.

The house was called a ‘one and a half’ because the upper room ceilings were sloping at the edges, higher at the centre. The largest bedroom was north facing and a gable sash window was its only light and ventilation. The middle room was a small box-room. It had no natural light or ventilation apart from leaving its door open. But a panel window between it and the next room allowed some light in. The next room had a gable sash window. It was bigger than the middle room and smaller than the north room. It got daytime sunlight and was cosier. It was over the kitchen as well. The walls had a lime plaster coloured sort of burnt orange.

The backyard was a few steps under the back door. The roof of the out-house was sagging and dangerous for our little children. We needed to take the roof off it. We have a sloped zinc roof there now and we use it for general storage. When we set about basic renovations within our small budget, the builder suggested we give it the bulldozer and start off fresh. We didn’t take that advice. We reared our family here. We modernised and enlarged it over the years since 1979 when they were teenagers.

Our house is the last house built in Coolcurtoga in 1877. Had we used the bulldozer as advised, this project would not have come about because we would not have kept the personal link between the house, its past families, and ourselves. We would have disconnected ourselves and life would have taken a different course. Now I am so aware of the other older houses here. Naturally I care about the people who lived in them and farmed this farm before us.

No boundary has changed here in our time, generations have come and gone but little really has altered. As a young farmer, Sean brought the farm from horse power to modern farming norms. It’s a rugged landscape and not a heavy-farm-machinery sort of place.

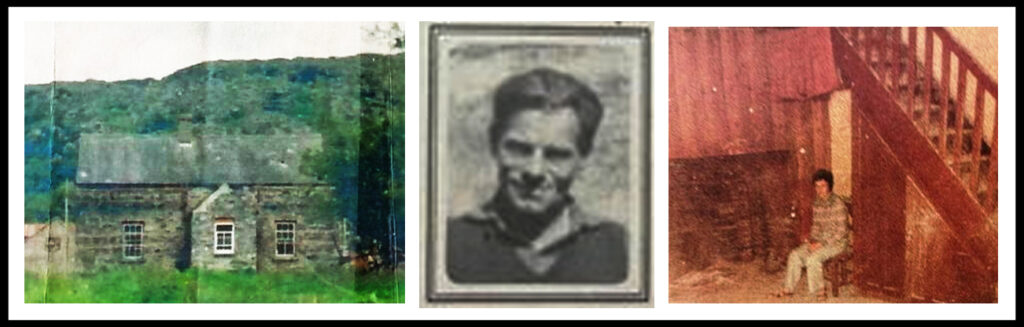

Sean shearing sheep in the 1980s and road making from the meadows to the top of Coolcurtoga

I regard Coolcurtoga as a microcosm of nineteenth century Ireland, its history could hold with all or any one of the townlands that constitute this country. My hope is that I have paid tribute in some small way to the people of Coolcurtoga who died or left our shores in the Famine or in times of hardship, and the many thousands if not millions who went that way with them. But most of all that the homes they left behind will be cherished and preserved in the future, as part of our national heritage.

Our four daughters grew up in the era of education and opportunity. On the last Saturday of June 2010, Anne, our third born, married. Sean asked the parish priest, Fr Radley, when the last bride left Coolcurtoga house to marry in the parish of Glenflesk. Fr Radley informed Sean it was exactly 103 years to the day that such ceremony took place, and the bride was Hanora, Paddy the American’s mother, eldest of the six children whose parents were evicted in 1892. This made a great wedding speech for Sean.

We are now the older generation here; we’re at a crossroads in our lives. I’m writing this sitting at Johanna Reardon’s fireside, the daughter of Daniel Reardon of Brewsterfield and Coolcurtoga. Isn’t that amazing.

The Houses

In the photograph above (left), which I took with my phone, you can see two small stone ruins amid the green fern growth situated down a rugged steep hollow. You will see to the top left a small green patch of a field way above the level of the two little houses, untouched for many generations. That patch is all garden ridges. In the image (centre), with the gable wall still standing, lived John Murphy, as recorded in the Tithe Register of 1833.[13] I think there are ridges behind John Murphy’s house and I recall ridges along the passage way up to the hill. Sean tells me there’s an old footpath. It’s overgrown now with ferns but when they die down the footpath can be seen. The gable end of another of the houses can be seen (right) with what looks like garden ridges, potato ridges. Only because the sun is low can the ridges be made out in that little green patch of ground. It’s a winter photo, the place is bare.

There are four other houses of only slightly larger size. I could tell by the measurements in the House Books which houses people lived in for 1848, 1850, 1852 and 1853. I was familiar enough with four of the houses but Sean took me way up the hill in the jeep and walked me along a high ledge to see the two tiniest little houses down in a rugged hollow.

My heart went out to its dwellers. A table wouldn’t leave room there for a chair. I had to visualise the scene at the time. The hills would have been dotted with the same. I had to think about the rugged landscape. The people would have had to be extremely agile. I thought about people living in igloos. Small. Bitter outside. Little children and older people. The strong would survive and the weak would die. I thought about the landlords eating their food at dining room tables. Servants. Hunting, fishing, gambling. Everything entered my head. I thought about the pluses too, small dwellings, only five minutes housekeeping, neighbours in similar little houses. I thought about trying to take a newborn baby down four miles in all weathers to baptise it, and trying to get a corpse to the old cemetery five miles away. I had so much pity for those people. Yet in 1848, they would have felt lucky not to have died in a ditch somewhere or be in the poor house.

We walk on the ground of our forebears. They owned nothing, and could not aspire to anything in an era of impoverishment and hardship. The only proof that they ever existed at all is through ledgers kept by landlords or church-tithe payments. They can be found on local church baptism or marriage registers where they are identified with their townland. Some are legible, others are not. But their little house ruins remain, memorials to the forgotten. I hope that something can be done to protect them as local heritage.

I haven’t a burial place for the inhabitants of the cottages in Coolcurtoga and Incholouchra but those ruins are testament to their lives. They are monuments to their deaths. This story mirrors so many others in this community parish in Kerry and indeed countrywide during this era.

I’m writing this now to preserve their memory. They were our forebears. It’s their story and I feel privileged to have researched it, to have put Covid-lockdown to good use for those who will follow us because we walk on their ground.

Let us never forget that.

____________________________

[1] Coolcurtoga (Cuil Cortioge or Tortog, a round rock). Spelling variations include Coolcartoga, Coolcurtogher. See logainm.ie for records of Incholohara, otherwise Inse an Ghleanna (Bend of the River Flesk). [2] Ellen O’Donoghue, daughter of Roger ‘booley’ Donoghue and his wife Catherine ‘Currig’ O’Donoghue lived with her sister Mary in one of the houses. Mary married Humphrey Moynihan; their daughter Johanna married constable Farrell Regan, his granddaughter is still living in the locality. Constable Farrell Regan was living here; his marriage certificate in June 1897 to Johanna Moynihan had his address Coolcurtoga. His marriage was witnessed by another constable. Farrell Regan and Johanna’s granddaughter is one of our neighbours. Johanna Moynihan’s mother was Mary O’Donoghue, daughter of Roger O’Donoghue named in the Tithe Applotment 1833. Mary was born in 1839 in what was then Incholohara, Roger O’Donoghue and his wife Catherine were her parents. Her sister Ellen was born 28/3/1830 and Jeremiah 29/4/1832 and Michael 22/6/1836. Mary was born 19/10/1839. Mary married Humphrey Moynihan on 12 February 1858. They had Mary (1861), Andrew (1863), Humphrey (1866), Catherine (1868). They had other children in Islandmore, the neighbouring townland across the boundary stream. Johnanna was one of them. So Johanna went to USA to earn her money to marry. When she returned she met Constable Farrell Regan living in Coolcurtoga. He had a steady job and she had a nest egg. They got married and lived across the stream in Islandmore. Johanna’s mother Mary was the daughter of Roger ‘booley’ O’Donoghue and his wife Catherine ‘Currig’ O’Donoghue. [3] The evaluation criteria was categorised A, B and C: A+ = built or ornamented with cut stone and of superior solidity and finish A = very substantial building and finish without stone or ornament A- = ordinary building and finish or either of the above when built 20-25 years ago Houses of medium age 25 years + B+ = medium but not new, but in sound order and good repair B = medium, slightly decayed by age but in good repair C = Old houses C+ = old but in good repair C = old and out of repair C- = old and dilapidated, scarcely habitable [4] John Burke had a house category 2C and his rent was 15 shillings and 9 pence Dunn Healy’s house was category 3C- and his rent was 2 shillings and 1 penny Daniel O’Sullivan’s house was 3C- and his rent was 2 shillings and 2 pennies Daniel Reardon’s house was 2B- for which his rent was £1-8-10 pennies The House Book names changed in 1850. The occupation period was from 19-12-1851 to the 13-4-1852. [5] Mary Reardon/Riordan married Jeremiah Healy. Elizabeth Reardon/Riordan married Gerald (Garrett) Fitzgerald on 25 January 1866. The marriage was witnessed by Daniel Fitzgerald and Michael Riordan. Elizabeth was to have Brewsterfield with her husband and three children. They continued in Brewsterfield until 1883. Garrett died in 1903 aged 60, Elizabeth died in 1923 aged 83. See Brewster of Brewsterfield: The Rise and Fall of Brewsterfield House, Glenflesk, Co Kerry c1675-1985 (2020) by Janet Murphy. Johanna Reardon/Riordan married Daniel Casey and Catherine Reardon/Riordan married Michael Dineen. [6] I have not been able to discover where Daniel and his wife Mary were buried. [7] Kerry Sentinel, 4 May 1892. Daniel Casey subsequently applied to the Killarney Union for outdoor relief; see Irish Examiner, 5 May 1892. The eviction report in full: A struggling but respectable tenant farmer on the property of Mr D C Coltsman JP (jnr) named Daniel Casey was evicted from his holding situate at Coolcurtoga (Glenflesk) for non-payment of rent. It would appear from the tenant’s statements that in consequence of his not being able to pay what he characterises an impossible rent, the relations between him and his landlord have been for a number of years estranged. He became tenant of the farm some twenty-one years ago having succeeded his father-in-law who was in possession of the place for a long time. The farm comprises about 5 acres of arable land with a mountain tract of about 800 acres. The arable portion of the holding is almost surrounded with a natural stream of water which in the locality is called a ‘cael.’ In wet weather, in consequence of the mountain streams flowing into it, this ‘cael’ becomes so swollen that the arable portion of Casey’s farm for a considerable part of the year is submerged. The public road is some 400 yards from the nearer bank of the ‘cael’ and the passage leading into it is very bad. It is only during the summer months that a foot passenger could get to Casey’s house with a dry boot. The original rent of the farms was £44 5s, the valuation being £30, which was advanced to £31 10s, in respect of additional buildings. Before the tenant went into possession he understood from the late Father Shanahan that the landlord would build a decent dwelling-house and out-offices on the farm, and on the strength of this understanding the rent was raised to £50, at which figure the farm had been held up to the year 1877. The tenant, by arrangement, was to procure all the materials for the buildings, the plans of which were drawn by Mr Nunan of Killarney. This landlord also promised to make a passage from the public road which he never did, but the tenant erected a quay which cost him £40. In March 1877, the tenant was behind time with his rent. The gale days were March and September, and he asked the landlord for time until July to enable him to sell some mountain stock to pay the rent. The request was refused. In September a full year’s rent would be due and in the following October an ejectment process for the amount was served on the tenant who settled out of court by paying £4 law costs having had to sell his cows to make up the amount. In the following year all the tenants on the property were allowed an abatement of thirty per cent. This concession Casey did not get the benefit of, but was put against arrears of rent for which an ejectment decree was obtained, no defence having been made. In some time after the landlord, through Father O’Flaherty, entered into negotiations for a settlement with the tenant who consented to pay £10, a clear receipt was given up to the previous gale day, and the future rent to be settled by arbitration. The landlord agreed to this, and accordingly the tenant appointed a respectable farmer in the locality named Jerry Kelliher his arbitrator, but when the matter came to a focus the landlord withdrew. The tenant was all along asking his landlord for an abatement in his rent, and when the rents of the other tenants were being arranged out of court his rent was reduced to £35, which was still too high. He paid several sums from time to time, but when, in the month of June 1891, the agency passed from Mr J D Curtayne into the hands of Messrs Hussey and Townsend all hope of clemency was at end. His cattle were seized and sold by public auction. His letter setting forth his grievances forwarded to the agents through Father O’Flaherty was answered with a writ, and finally his interest sold out by the sheriff at Tralee, and bought in by the landlord. The tenant’s family have been on the property for ever so long, and when he went to live at Coolcurtoga he had £550. After twenty-one years of toil and worry, he was, he says, evicted from the place without a penny. The Shrieval party, which consisted of two bailiffs from Tralee, and a representative of the agent’s named Spunner, arrived at the place at midday. They were protected by a small force of police from Killarney. When the house was reached the ‘brigade’ found the door barred against them. One of the bailiffs broke in the door and possession was taken without any further resistance. Casey has six children – all of whom are girls – and a wife. The second youngest of the children was sick and confined to bed with influenza. When the furniture was removed from the house one of the bailiffs approached the sick child with the object of disturbing it after his rough manner. He said the child was only ‘shamming’ whereupon the father protested and said he would cling to his child to the last, as he valued it more than Mr Coltsman’s whole property. A hand-to-hand encounter between Casey and the bailiff was arrested by the police by putting the latter out of the house. The sick child having been tenderly removed by its mother, the eviction was completely carried out. An emergencyman and two police were left in the house, while Casey and his family had to seek shelter from their neighbours for the present which was generously afforded to them. A dispute about Daniel Casey’s pension application, which was heard in 1911, alluded to the dark days when he was evicted: ‘Having been an evicted tenant for some time he had no means to carry on the farm, and he got his daughter Hannah married to Cornelius O’Donoghue, and the latter took up the farm. He applied for an old age pension, and there was some delay about the registration of the deed of conveyance. In the meantime a sum of money came from a brother in Australia in two amounts, and it was clear that before any Pension Act came into force he intended that this money should lie in trust for his children. It was not a case in which the Bench should publicly brand this old man, with the shadow of death hanging over him, as a criminal. The case was dismissed. See Kerry Weekly Reporter, 23 December 1911. It is worth noting that the ‘Mr Nunan of Killarney’ referred to above was architect and building contractor Francis Nunan (or Noonan) (1830-1904), brother of Denis Noonan, National Teacher at Rathcormac, Co Cork, who died at Killarney on 25 August 1893, and Joseph Denis Nunan (1842-1885), Fenian, transported to Fremantle, Australia in 1867 (where he remained and married, establishing a reputation as a builder). Francis Nunan took up residence in Killarney in about 1854 where he befriended ‘the peer to the peasant’ (obituary, Kerry Evening Post, 19 March 1904). His building projects included, in 1868, the erection of St Mary’s Church of Ireland Killarney; erection of the Presbyterian Church in New Street, Killarney (same year, 1868); erection in 1875 of the Presentation Convent Killarney, designed by J J McCarthy RHA; Munster and Leinster Bank Killarney ‘on the site of the old Hibernian Hotel opposite the Protestant church in Lower Main Street’ (opened in January 1877 ‘on the ground where the Kenmare Arms Hotel formerly stood’); alterations at Killarney House in 1884, the restoration of St Mary’s Church of Ireland Killarney after a fire in 1888, erection of Glenbeigh Church of Ireland 1890, alterations and improvements to Aghadoe Church of Ireland in 1892, at the request of John McGillycuddy Esq; monument to the wife of Dr Griffin at Park View Cemetery [New Cemetery Killarney] in 1894. Bessie, wife of Francis Nunan, died at her residence, Main Street, Killarney on 5 December 1900, funeral from Killarney Cathedral for Aghadoe after Requiem High Mass ‘American and Australian papers please copy’ (funeral report Kerry Sentinel, 12 December 1900). Francis Nunan died at Church Place, Killarney, on 12 March 1904. Funeral held at Killarney Cathedral; his remains were interred in the family vault at Aghadoe. Among the chief mourners his cousin, Thomas O’Mahony, builder, Fermoy. [8] Mention was made of Coolcartoga Protection Post in a case taken by Sergeant Alexander Smyth against Constable Timothy McCarthy (and vice versa) in 1892 about standards in policing. The court of inquiry was held in the Headford police hut near the railway station. The case received publicity, and the proceedings gave the names of a number of policemen working at that time, including Constables Charles Carney (Canny), Crumby (or Crumley) and McCullogh, as well as information about working conditions of the time. See Kerry Weekly Reporter, 31 December 1892 or Irish Examiner, 27 December 1892. It is worth noting there was a barracks situated at nearby Killaha. It was styled ‘Police Barrack’ on the early OS map. The later map shows a restructured building. In the 1930s, an entry in The Schools’ Collection gave the following: Killaha barracks: This old ruin is situated in Killaha near Fr Godley's entrance gate. It was originally built for Orpen's workmen as a lodge. Later it was occupied by the RIC Sergeant Roe, Constables O'Callaghan, Murphy, Ryan, Regan. They left it and went to Loo Bridge. In January 1891, RIC Sergeant Peter Thomas Roe charged Constable Conneffe of being drunk at Killaha Hut on 12 December 1890. An investigation was conducted in Killarney, court composed of District Inspector Graves, Kenmare, District Inspector Rice, Castleisland, prosecuted by District Inspector Hill, Killarney. It transpired that Constable Conneffe was stationed in Killaha Hut with ‘Constables Kenny, Murphy and Dignan.’ Conneffe was fined £1. Roe seems to have been later stationed in Dingle (1892-1894). In June 1891, three men from Headford, Michael Healy, Jeremiah Healy and Patrick Rahilly were arrested for assaulting a man named Henry Williams of Brewsterfield on 27 May. It was stated in the report of this event that 'latterly a police hut has been erected at Killaha in the vicinity of Brewsterfield’ which suggests the building was renovated during the Land War. In December 1891, two police constables from the Killaha Hut, James McVeigh from Tyrone and Patrick Rooney from Sligo were drowned near Derrynacullig, Loo Bridge (an elaborate memorial cross was later erected at Park View Cemetery (known today as Killarney New Cemetery) inscribed (in capitals): In Memory of/Patrick Rooney/and/James McVeigh/R I Constabulary/ Drowned in the Flesk whilst on Duty/26th December 1891/Erected by their Comrades in the/Killarney District/RIP – an image of the memorial can be viewed on www.kerryburials.com). ‘Fr Godley’s entrance gate’ was the former entrance to Killaha House, the residence later utilised as a presbytery. Nothing remains of the old barracks. The following account of the parish of Killaha, published in the Kerry Evening Post, 14 January 1891, is of interest. ‘Glenflesk, County Kerry. The river Flesk, which rises in the mountain range which flanks Rathmore, and falls into Loch Lean, gives its name to Glenflesk, a wide valley narrowing above Killaha, and winding among the mountains which part the counties of Cork and Kerry. A hundred and sixty years ago these mountains swarmed with the most dangerous rebels, who swept over the country periodically as a scourge. Glanflesk was the hereditary estate of the Sept of the O’Donoghues of the Glens. They were dispossessed under the Commonwealth but the new owners never ventured to take possession. Killaha Castle, the old O’Donoghue stronghold, was occupied by the family till about 1750. After the battle of the Boyne, a number of the Milesian cousinship, driven from the plains, found a welcome in Glenflesk where, in mud cabins round the castle walls, they lived at their ease. Here, at Foiladown, Owen’s bed is still shown – the wild refuge of an outlaw who lost his life after a brave defence. His head was set up on a spike in the market place of Macroom, and his body left to the eagles and wolves still lingering in the mountains of Ballyvourney. Rev F Bland and Mr Brewster, his brother-in-law, had set up iron works in Glenflesk, which was then clothed with forests, and close to Brewsterfield remains of crystalline ‘slag’ still glisten on the roads. The rapparees of the valley would not allow the iron to be carried to Cork and thus one more Irish industry was crushed. The Glenflesk people carried long knives, or skeans, and they used them freely when attacking the house of the peacefully disposed. Beside the ruins of the Castle of Killaha, which crowns an eminence at the head of Glenflesk, the lowly walls of the ivy-covered church of Killaha still stand in their enclosed graveyard. The church, which is correctly orientated, measures 62 x 30 feet. The door as is customary in all these old churches, is an arched one, near the west end of the south wall. An old skull, twined with ivy roots, is built in a hole in this arch, near the well-moulded Holy Water Stoup. On the inner sill of the east window, and on a piece of fallen stone mulion, which lies near, are scratched or cut nine rude crosses, which, by the persevering efforts of devotees who for many centuries have ‘given rounds’ there, are some of them hollowed to the depth of three-quarters of an inch. Every pilgrim traces each cross with a bit of stone, or slate, or a pin. Empty whiskey bottles lie on many graves. ‘Departed his life’ is the wording on several tombs. And on one slab is an inscription in Irish, followed by the translation: Pray don’t intrude, or move a lonely tribe/That’s here entombed, secluded from your strife./If you presume to scoop this vault, not thine;/May god beshrew thy rude supplanting guile. The church of Killaha is visited by crowds on February 5th, and rounds are then given. Feb 5th being St Agatha’s Day, it occurred to us that Killaha may mean Church of Agatha, and on consulting Bishop Reeves, he says that on Feb 5 the ancient Felire of Aengus the Culdee has this quatrain: Crucified was the body of Agatha,/The champion with purity,/By Jesu, with whiteness,/She hath much good upon her. ‘I am inclined,’ says the Bishop, ‘to withdraw any hesitation which I at first felt about your suggested derivation, and accept Agatha under the Irish veil of Echtagh, which with Kill will readily form Killagha.’ About two miles up the valley is Cahircourcarrig, or ‘the city,’ a rath where rounds are given on May Day Eve, and sick cattle brought from very great distances to be healed – some, we learned, as much as 60 miles. ‘A bull once stolen by a thief from this rath was traced by the marks of its hoofs and of a knobby stick borne by the culprit, and the marks are still to be seen turned to stone.’ And so much for Glenflesk!’ [9] The address on the birth certificates was Coolcurtoga, John Rutherford, a caretaker. [10] The Census of 1901 records Scottish born 34-year-old Kate Rutherford in occupation as an asylum nurse at the then Killarney District Lunatic Asylum at Ballydribbeen. Her three children were boarders at Gortagullane with widow Anne Simms and her 18-year-old daughter Ellie. [11] Census of Ireland 1901 (Coolcurtoga): Daniel O’Donoghue ‘Caretaker’ age 45 and his wife Hanora O’Donoghue age 47. Elizabeth Reardon and her husband Garrett Fitzgerald were in the Brewsterfield census data they were living with their daughter. Living in the house that census night was her sister Johanna Casey and niece Helen Casey. I could not find Daniel Casey or the elder daughters because Daniel had gone to the USA to work as hard as he could to earn enough money to return to Coolcurtoga and buy it. I’m not certain in which year he emigrated though probably soon after the eviction. By the time of the Census of Ireland 1911, Daniel Casey aged 70 retired farmer and his wife Hanna Casey aged 69 were living at Coolcurtoga with Cornelius Donoghue age 40 and his wife Hanora Donoghue age 38 and their children Abby aged 2 and Hanna aged 1. [12] ‘Died on May 5 1978, at St Anne’s Hospital, Killarney, Patrick O’Donoghue, Coolcurtoga. Deeply regretted by his loving brother, relatives and friends RIP. Remains will be removed this (Saturday) evening at 5pm to Glenflesk church. Requiem Mass on tomorrow (Sunday) at 11am. Funeral immediately afterwards to Killaha Cemetery’ (Irish Examiner, 6 May 1978). [13] Tithe Applotment Books 1833, parish of Killaha, townland of Coolcartoga (sic), occupants John Murphy, Denis Healy. Townland Incholohara, occupants Daniel Healy, Roger Donoghue. It is worth noting here that in 1894, an eviction notice was served on Denis Healy of Killaha, landlord D C Coltsman JP Killarney, Agents Messrs Hussey and Townsend (Freeman’s Journal, 21 September 1894).