Michelle Kranjc, a descendant of John Heffernan and Mary Mullins of Caheragh, Castleisland, contacted Castleisland District Heritage recently about her ancestors who left Castleisland with Edward Hogan and his family of Caheragh after the Famine. They were resident in Hamilton, Ontario by 1857.[1] Michelle is hoping to find out exactly when they departed and if descendants of the family remained (or remain) in the area.

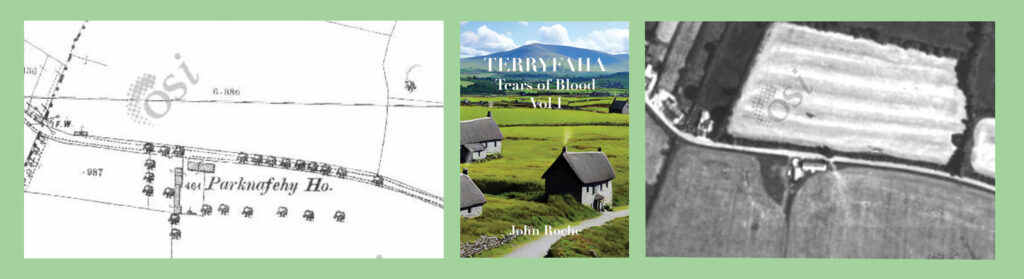

Parknafehy House at Caheragh was the ancestral home of John Roche, Chairman of Castleisland District Heritage. His great grandmother moved to Parknafehy in 1848 after her husband died from fever. The house (demolished some years ago) stood on a road known locally as Powell’s Road after a family by that name once in residence there. John has described in vivid detail the exodus of people from the district in his book, Terryfaha, which is based on true stories inherited around the fireside in his youth.[2]

Michelle is one of five individuals working to find a location in Hamilton for a pair of bronze Famine Shoes sent to Canada from the Strokestown Estate in Roscommon, part of the National Famine Way project. She writes, ‘Sending six pairs of Bronze Shoes to Canada extends the National Famine Way into to a Global Irish Famine Way. The RV Celtic Explorer left Galway and arrived in St John’s, Newfoundland in early May with this precious cargo. This initiative is supported by Eamonn McKee, Irish Ambassador to Canada.’[3]

The Hamilton Committee was formally presented with their Bronze Shoes recently at the Canadian, Ireland and Transatlantic Colonialism (CITC) Conference at St Michael’s College, University of Toronto. Michelle informed us that Ireland was well represented with scholars from University College, Dublin, Trinity College and University of Galway:

One theme that was mentioned, more than a few times, was the importance of oral history. I’m so grateful that you mentioned John Roche’s book, Terryfaha, to me. I have located a copy.

The Bronze Shoes were presented to the representatives of the Hamilton Committee by Eamonn McKee, the Ambassador of Ireland to Canada. Michelle writes:

We will be sad to see him leave Canada in a few months as his tenure is over. He has worked tirelessly in promoting the Global Famine Way and walked the National Famine Way the week before the conference with Jason King of the Irish Heritage Trust.[4]

A booklet, The Irish Famine (1999) by Gail Seekamp and Pierce Feiritear was recently added to the archive of Castleisland District Heritage.[5] It describes the Great Famine in an informative manner, quite unlike the graphic scenes given by John Roche in Terryfaha. It includes an extract from a letter written by emigrant ‘Margaret’ in America. It is addressed to ‘My dear father and mother, brothers and sisters’ in Kingwilliamstown, and dated 22 September 1850:

I can assure you there are dangers and dangers attending comeing here; but, my friends, nothing venture, nothing have. Fortune will favour the brave. Have courage and prepare yourself for the next time that worthy man, Mr Boyen is sending out the next lot, and come you all together courageously and bid adieu to that lovely place, the land of our birth, but alas, I am told, it’s the gulf of misery.[6]

‘The gulf of misery’ was an accurate description. In the extract below, John Roche draws on oral lore to depict the Famine in ‘Terryfaha’ after fever strikes a small settlement, wiping out almost all of the occupants:

It was a misty Friday morning in June, and having finished the regular chores, Nora saw an opportunity to pay a visit to the Faha, as she had done hundreds of times since coming to Terryfaha. When she neared the end of the passage, she saw an object in the mud at the entrance to the rough rocky commonage. She had a premonition of impending doom as she figured it was the body of a child, and getting nearer still, she recognised the clothes. She ran stumbling, panicked, and caught a glimpse of a brown coloured animal scurrying towards the high bog – a fox. If she didn’t recognise the clothes that she had brought to her favourite boy, Brendan, it would be impossible to recognise him. He was black, bloated and putrefying, and though her first instinct was to drop down and put her hands on him, she found her breakfast in her mouth and had to heave it all out.

Nora bravely approaches one of the little houses but ‘any hope that remained in her breast was quickly erased when she got the smell’:

She stood transfixed, looking at what had been a family only a couple of days ago. She backed out the door and stood for a while, shocked and stupefied, not knowing where to turn. The next two houses were vacant, the families thankfully gone across the water, and then there was Brennan’s. The older members were also in America but there should be six or seven of them, parents and children, left in the thatched hut.

Nora, finding the door closed, fearfully, ‘her knees buckling under her with weakness,’ pushes the door in:

Nora recoiled from the blast of unholy stench that enveloped her senses and caused her to swivel and put her back to the jamb of the door as she puked for about the tenth time. She stood there, weak and exhausted, wanting to flee the scene, but she couldn’t without checking that they were all dead inside … getting cloth over her mouth and nose, she crouched and entered the dark mud-floored hovel and she could hear herself crying out loud as she stepped slowly towards where the fire should be, seeing the grotesque forms as her eyes became accustomed to the lack of light. The rats were actually squealing back at her, seeming to be annoyed at being disturbed, and she found herself screaming hysterically back at them before she realised that she must get out of there.

Michelle Kranjc would very much like to add her own Famine story to the Global Irish Famine Way project. If anyone can assist Michelle with her Heffernan family history in Castleisland, please get in touch with us.

_____________________

[1] Michelle Kranjc has a baptismal record for Michael Heffernan, son of John Heffernan and Mary Mullins on 12 July 1857. John Hogan was a sponsor. [2] In relation to a question about an Irish Dog Tax, it was said of Henry Arthur Herbert (1840-1901) MP and Grand Juror, ‘As a landlord, the only portion of his estate that ever fell into his immediate possession was Breahig, Kilcow, Knockaneafincha, Caheragh and Parknafeaha, near Castleisland, the life of which died some 18 months since. His instruction to his good and kind agent was to root everyone to the soil, large and small, whom he found there before him. This was no easy task as some of those townlands, especially Breahig, was overcrowded with small crooked buildings, let some hundreds of years since … at last road sessions he put a hand into his pocket and paid down £400 to make a road for them which will also be a most useful county road and an immense boon to the parish’ (Kerry Sentinel, 25 July 1879). An article about moonlighting in Caheragh was published in the Kerry Sentinel, 26 November 1886. [3] By email 23 May 2024. [4] By email 2 June 2024. [5] IE CDH 196. The booklet includes an illustration of a capstan mill in operation at Hive Iron Works, Cork. It is worth noting that a capstan mill is illustrated on a nineteenth century map of Tralee Prison close to where the gallows was erected to execute Poff and Barrett in 1883. [6] ‘Margaret’ alludes to Michael Boyen, agent for Crown lands at Kingwilliamstown. Michael Boyen of Greenfield, Kanturk married Anne McCarthy of Drominargle, Newmarket, Co Cork, first cousin of Daniel O’Connell. His daughter Katherine Gertrude Boyen married into the Moloney family.