About the year 1836, a young man named John O’Donovan was despatched by the office of the Ordnance Survey to visit in succession every county in Ireland with the object of noting and recording all existing remains of antiquity:

By the direction of the Ordnance, O’Donovan visited, we may say, every townland in Ireland, thus acquiring an amount of knowledge of Irish topography and an acquaintance with local traditions and dialects, never previously nor since attainable by any individual. In these journeys, and in settling the orthography of the names in the Ordnance maps, he was mainly occupied till the sudden and unexpected dissolution of the topographical section of the Survey in 1842.

It was a unique job. Sir Thomas Aiskew Larcom, Superintendent of the Ordnance Survey, had ‘conceived the grand idea’ of making the work of the Ordnance Survey ‘embrace every species of local information relating to the country,’ and to Larcom – in the form of letters – O’Donovan reported.[1]

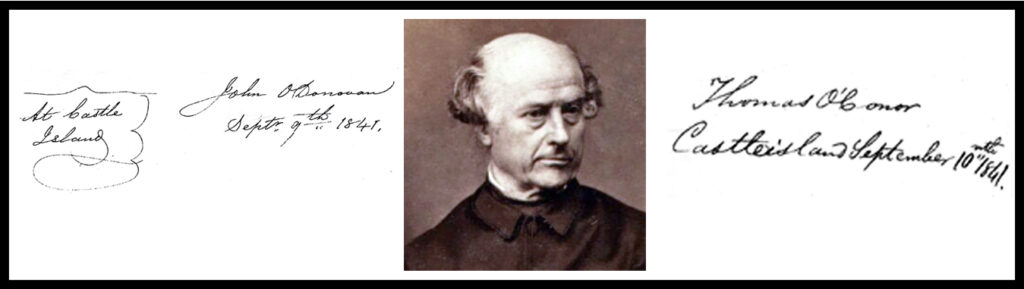

In September 1841, O’Donovan was in Castleisland with his colleague, Thomas O’Conor.[2]

On September 10th, the two men, who evidently divided the parishes in the barony of Trughanacmy between them, worked almost side by side. O’Donovan concentrated on Castleisland and O’Conor focussed on Ballincuslane.[3]

It is easy to imagine the two men taking refreshments in one of the inns in Castleisland town, deep in conversation about the antiquities they had that day measured and documented.[4] O’Donovan, however, certainly played down the task in a letter to Captain Larcom on the 22nd of the same month:

We have identified some very curious localities in Kerry but the reading of the letters will be very tiresome as they consist principally of measurements of old churches, castles, stone cells, &c &c.

The following year, the plug was pulled on the project.

The Letters

Seventy years later, a writer asked about ‘the desirability of publishing the Ordnance Survey Letters of Ireland’ as they constituted such ‘a valuable asset in the historical, topographical, and antiquarian records of the country.’[5]

The writer gave a brief outline of the progress of the letters since the project came to its sudden halt in 1842. The Royal Irish Academy had stepped in to help, and a Commission appointed in 1843. The Commission recommended the recommencement of the work, but it came to nothing. The Great Famine intervened, and the papers were deposited in Mountjoy barracks.[6]

In 1860, the Royal Irish Academy applied to the Government for custody of the documents, and in November of that year more than 100 volumes of manuscripts with eleven volumes of antiquarian drawings, fully indexed and bound, were presented to the Academy:

After a vote of thanks to Colonel James and Lieutenant-Colonel Leach, by whose hands they were deposited, the Academy testified to the importance of the services rendered to the history and antiquities of Ireland by Sir Thomas Larcom, and thus ended the story of Ordnance Memoirs of Ireland.[7]

The documents remain in the custodianship of the Royal Irish Academy.[8] Its website reveals that printed editions of the letters for selected counties have been published, almost all of them prepared by the late Michael Herity of Ballintra, Co Donegal, Professor Emeritus of Archaeology at University College, Dublin.[9]

Thanks to modern day technology, the work undertaken by O’Donovan and O’Conor covering the entire county of Kerry is now accessible online, a standard source of reference for researchers, particularly useful in comparing the condition of buildings in pre-Famine Ireland to today. Some buildings in Kerry, like Ballymacadam Castle, have since disappeared.

John O’Donovan, Antiquarian

The death of the translator of the Annals of the Four Masters cannot be considered otherwise than as a national calamity – Irish Examiner, 11 December 1861

John O’Donovan was born ‘of very humble parentage although descended from as distinguished ancestry as any in Ireland.’[10] His father, Edmond O’Donovan, was born at Kilcolumb in 1760. Edmond was a farmer, described as a large, strong and very courageous man. In 1763, Edmond moved to Atateemore, Slieverue, in the parish of Kilcolumb, and in 1789, married Eleanor Hoberlin of Rochestown, Kilkenny. John, his fourth son, was born on 26 July 1809.[11]

Edmond O’Donovan moved to a farm at Redgap, Kilcolumb in 1816 and died the following year, on 19 July 1817, leaving his young family in poor circumstances.[12]

John, a boy in his eighth year, derived an education from a number of sources, including his uncle Patrick O’Donovan, and some knowledge of Latin and Greek from a relative (a priest) supplemented by an education in an Irish hedge-school.

He later found work as a clerk and steward ‘to a gentleman residing in the Queen’s County’ and there the directors of the Ordnance Survey chanced to find him:

They were astonished at the amount of topographical and historical information which he was enabled to afford them. He was taken into the service of the Ordnance Commission and henceforth became recognised as a remarkable man.[13]

O’Donovan thereafter remained in Dublin. His considerable output included a translation of the Annals of Ireland, ‘the grandest and most learned historical publication ever edited in these countries by an individual scholar,’ and The Book of Rights.[14]

O’Donovan’s labours were duly recognised and honours conferred on him including Doctor of Laws by TCD. However, the accolades and adulation did not reflect in his financial standing:

O’Donovan received no sterling support or recognition from the high and opulent in his own country and while large sums were weekly lavished in Dublin on trifles of the hour, the great scholar, whose profound works had in every part of the world obtained a respectful recognition for Irish learning, was permitted to remain at home obscure and unnoticed except by the few who knew how to value his labours and to appreciate his character.[15]

O’Donovan considered emigrating to obtain better prospects for his large growing family but ‘fortunately for learning and for Ireland’ he remained in the country. He obtained an appointment with Eugene O’Curry, transcribing and translating the Brehon Laws to which he applied himself ‘with his characteristic assiduity and self-denial, never sparing an hour for relaxation.’[16]

‘P.23 Ends.’[17] – The last words written by Dr O’Donovan

The straightforward simplicity of his character made for him a friend of every one with whom he had even casual acquaintance – Obituary, Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine

John O’Donovan could be seen taking his daily exercise in Dublin in all weathers, ‘often struggling against storm and hail, yet intently pursuing his course’:

He never could be induced to avail himself of a vehicle, erroneously imagining that walking exercise, even in the most tempestuous weather, was necessary as a counterpoise to the sedentary pursuits which consumed so large a portion of his time. In unwisely indulging in one of these excursions, he caught his mortal illness.[18]

O’Donovan suffered an attack of rheumatic fever and died at about twenty past midnight on the night of Monday 9 December 1861 from ‘inflammation of the bronchial tubes.’[19]

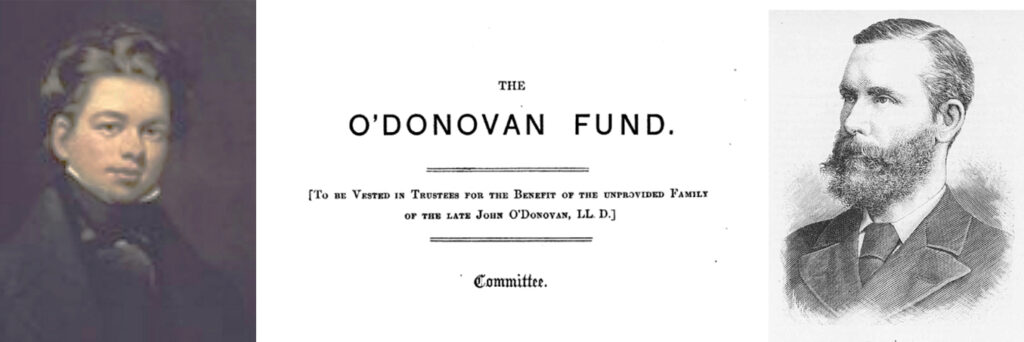

On Thursday 12 December 1861, Dr John O’Donovan was laid to rest in Glasnevin in a plot assigned by the Cemetery Committee alongside the sculptor, John Hogan.[20] A few days later, a special meeting was held by the Council of the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society to open a public fund for O’Donovan’s widow and six sons.[21]

With the death of Dr John O’Donovan, certain branches of Irish learning were said to have perished. Many tributes followed. One described how his ‘career of usefulness’ began on the Irish Ordnance Survey ‘when a mere boy.’ When Eugene O’Curry later joined that service, it ‘laid the foundation for the productions of both gentlemen that have arrested the attention of the learned of all nations for the last quarter of a century or more.’

They have laboured together as on the Survey, the Brehon Laws, and for the Archaeological Society; and separately, as on the Annals of the Four Masters, and the MS Materials of Irish History.[22]

Another gave a measure of O’Donovan’s ability:

He had to contend with the obscure and obsolete idioms of a peculiar language and to seek his authorities and illustrations among our unclassified and un-indexed Celtic monuments – half-effaced by the accidents of time, and which would still remain unintelligible and inaccessible to the literary investigator but for the labours of himself and his erudite associate, Eugene Curry.[23]

Of O’Donovan’s translation of the Annals of Ireland, the writer added:

It must be admitted that these Annals, as edited by Dr John O’Donovan, form one of the most remarkable works yet produced in the history of any portion of the British Isles. The mass of information which they embody constitutes a collection of national records, the value of which can never be surpassed.[24]

The O’Donovan Curse

John O’Donovan had the greatest interest in his ancestry. Writing to Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Skibbereen, Co Cork, from his home at 36 Upper Buckingham Street, Dublin on 24 December 1854, he described how he feared the Donovans were ‘doomed to extinction – many curses hang over us!’:

The holy Columb MacKerrigan, bishop of Cork, cursed our progenitor, Donovan, from whom we all descend (and our names, Donovanides), in the year 976, in the most solemn manner that any human being ever was cursed or denounced, and so late as 1652, a good and pious Protestant woman’s family (the children of Dorothy Ford) cursed Daniel O’Donovan of Castle Donovan and caused a Braca Sinshir (Aillse) to trickle from a stone arch in Castle Donovan which will never cease to flow till the last of the race of the said Daniel O’Donovan is extinct. It appears from the depositions in Trinity College Dublin that the said Daniel O’Donovan and Seige A Duna MacCarthy hanged the said Dorothy at Castle Donovan to deprive her and her family of debts lawfully due unto them. You and I escape the last curse but we reel under that pronounced by the holy Columb.[25]

In another letter to the same correspondent in 1860, O’Donovan remarked again on family history:

Our ancestor, Donabhan, son of Cathal, was certainly a singularly wicked and treacherous man, and it is to be hoped that his characteristics have not been transmitted, and, therefore, that the curse of the good Coarb of St Barry has spent its rage long since. But I believe that the curse still hangs over us.[26]

The Family of Dr John O’Donovan

O’Donovan’s concerns about the curse were certainly borne out in the lives of his own children. He married, on 18 January 1840, Mary Anne (or Marianna) Broughton, daughter of John Broughton of Killaderry, Broadford, Kilseily, Co Clare. Nine sons were born to them, six survived to adulthood.[27]

The youngest was only five years old when his father died in 1861. About five years later, Mrs O’Donovan, then in receipt of a government pension, left Dublin with her family and returned to Co Clare. A property, Crean Mount (otherwise ‘Glenview’) was purchased near Broadford and became the family home.[28]

The deaths of Mrs O’Donovan’s three eldest sons occurred in her lifetime.

John O’Donovan (1842-1873) John O’Donovan left Ireland after being imprisoned on charges of Fenianism. He was professor of English literature and natural science in the Christian Brothers’ College, St Louis, Missouri. He drowned on 23 June 1873 while swimming with friends in Creve Coeur Lake and was buried in Calvary Cemetery. In later life, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa wrote that he feared his own early acquaintanceship with John O’Donovan’s sons ‘had something to do with disturbing the serenity of their lives in after years.’[29] Edmond O’Donovan (1848-1883) ‘O’Donovan of Merv’ ‘Howie Wylie, when at Portpatrick the day after the sinking of the SS Orion, found a small Irish boy on holiday from Dublin sketching the funnel and mast of the sunken steamer protruding out of the water. Mr Wylie begged the sketch from the boy, sent it to London, and it appeared in the Illustrated London News, then a struggling journal, as ‘by our artist on the spot.’ A cheque in payment came by return of post and was handed to the boy’s mother by Mr Wylie. The boy, Edmond O’Donovan, son of Dr John O’Donovan, the well-known Celtic scholar of Dublin, was thus introduced to journalism, becoming the famous war correspondent who was lost in the annihilation of Hicks Pasha’s ill-starred expedition in the Soudan.’[30] Edmond O’Donovan was author of The Merv Oasis Travels and Adventures East of the Caspian during the Years 1879-80-81 (1883, 2 vols) in which he wrote, ‘These pages contain a simple record of my wanderings around and beyond the Caspian including a five months’ residence at Merv during the three years 1879-1881.’ Shortly before he was reported to have perished in the Soudan, Edmond wrote to a friend, ‘To die out here with a lance-head as big as a shovel through me will meet my views better than the gradual slow sinking into the grave which is the lot of many.’[31] It was held by some that O’Donovan was not killed in 1883 as his body was never recovered. Others, including his mother, maintained that he was the White Pasha.[32] An article, ‘Edmond O’Donovan, Fenian and War Correspondent, and his Circle’ by Eva O Cathaoir includes photographs of Edmond O’Donovan.[33] William O’Donovan (1846-1886) On news of the presumed death of his younger brother Edmond in 1883, William O’Donovan addressed the editor of the Boston Republic newspaper correcting a few errors that had appeared in a tribute. Writing from New York on 1 December 1883, he stated, ‘Edmond was not born in Kilrush, county Clare, but in the North-strand, Dublin City, and the date of his birth was September 13th, 1848. He was never Paris correspondent of the Irishman as I occupied that position from the time it was given up by John Augustus O’Shea until the close of the Prussian siege of Paris ... Your contributor confuses him during the Carlist war with a younger brother, Henry, who was in the medical service of Don Carlos, and was imprisoned by the Royalists for an indiscreet profession of Republican principles. There can be no mistake about this as it was I who applied to Cardinal Cullen and the present Bishop of Ardagh, then Rector of the Dublin Catholic University, to intercede on behalf of Henry ... I may add Edmond was never married either to a Khan’s daughter or anyone else.’[34] William O’Donovan joined the Fenian movement while a student of Trinity College Dublin. He was elected by that movement to receive funds brought over by John Mitchel and was dubbed, ‘The Chancellor of the Exchequer.’ William O’Donovan worked as a journalist in Paris and New York, and died from Bright’s disease in New York on 25 April 1886 at the age of 41.

Three sons, Richard, Henry and Daniel, survived their mother.

Richard O’Donovan (1849-1939) Richard O’Donovan of Norfolk Avenue, Prestatyn, Flint, was the only son to marry. In 1875, Richard went to Liverpool en route for the United States where he intended to join the Christian Brothers. However, he was persuaded to remain in the city by William Horan, a member of the Fenian organisation in Liverpool, and secured work as translator in the Royal Insurance Co, Liverpool, where he remained for over 43 years until his retirement.[35] He married, in 1881, Anna Maria Cahill (1854-1930), daughter of William Cahill of Ennis. They had one daughter, Maria (or Mya) in 1882, who married on 28 April 1903 Dr William Pritchard-Airey (1866-1950) of Menai Bridge at St Peter and St Paul’s Church, New Brighton. Richard O’Donovan was then resident at Woodbine Cottage, New Brighton, Wirral. In 1919, Richard settled in Prestatyn to be near his daughter. His wife, Anna Maria O’Donovan, of 7 Norfolk Avenue, Prestatyn, died on 1 January 1930 at 38 Bentley Road, Princes Park, Liverpool and was buried at Wallasey. Richard O’Donovan of Norfolk Avenue, Prestatyn, North Wales died at Painton, Prestatyn, Flintshire on 10 June 1939 in his 91st year. His funeral service was held in SS Peter and Francis’s Church, interment at Coed Bell Cemetery, Prestatyn. His headstone there is inscribed (in Latin): Hic Oucoue Jacet/Ricardus O’Donovan/Filius Joannis O’Donovan LL.D M.R.I.A./Die X Mensis Jun 11 Anno Salutis MCMXXXIX/Annos Natus XCI/RIP/Maria Pritchard Airey Filia Dilectissima Moerens/Patri Suo Hoc Monumentum. Richard O’Donovan left property on trust for his brother, Daniel Cornelius O’Donovan for life. Mrs Pritchard-Airey died in December 1969 in St Asaph, Flintshire, Wales with no surviving issue, and thus the line of Dr John O’Donovan would seem to have come to an end. Henry O’Donovan (1853-1905) Henry O’Donovan endured ‘months under the death sentence in a dungeon at Estella on a trumped-up charge of having plotted the poisoning of Don Carlos.’ This event occurred in 1874: Henry O’Donovan, a philanthropic Irish gentleman, whose exuberant benevolence induced him to go on a Samaritan mission among the Carlists. He has returned to St Jean de Luz after a series of adventures which have made him a wiser man. That he did not die in a Carlist dungeon or meet with the same sad fate as Captain Schmidt is owing to the kind offices of Mr Furley who managed to obtain his liberation and bundle him off to France when no letters from Cardinal Cullen and other influential persons had any effect on the hard hearts of the Santo Officio.[36] Henry described his experiences in a letter to his brother in Spain, written from St Jean de Luz, where he was lying ill. He explained how he had been accused of being an emissary of the Ronda Secreta of Madrid because a preparation of laudanum he carried to help him sleep was observed in his room by a padre cara. Henry was reported and informed that he was, ‘without doubt,’ an assassin of Carlos VII and he was packed off to the Carcel of Estella. Henry’s description of his prison ordeal reveals he was most fortunate to survive.[37] The progress of Henry O’Donovan’s life from this point is open to research. He is stated to have worked in England as assistant physician in the north of the country. Indeed, the UK Census of 1881 records 28-year-old Henry O’Donovan, medical assistant, in Manchester. In this respect, it is worth noting that a writer in 1883 described one of Dr John O’Donovan’s sons as a surgeon in Lancashire who ‘acted as Premier to Oko Jumbo, an African king on the shores of the Bonny River for a short period.’[38] Henry O’Donovan was present at his mother’s death in Co Clare in 1893. After this, he seems to have returned to England where he evidently fell on hard times.[39] He died in North Riding Lunatic Asylum, York on 23 September 1905. He was buried in York Cemetery.’[40] Daniel Cornelius O’Donovan (1856-1932) The life of Daniel (Donal) Cornelius O’Donovan is open to research. The UK Census of 1911 shows that he was living with his niece, Mya Pritchard-Airey and her husband in Wallasey, Merseyside. He was single, aged 54 and his occupation was given as chemist and druggist. He was remembered in the will of his brother, Richard. His date of demise is given as 23 October 1932. He was buried in Coed Bell cemetery, Prestatyn.

Mrs O’Donovan died at the family residence, Glenview, ‘to the general regret of the whole countryside amongst whom she was a familiar and kindly and beloved presence’ in June 1893.

With her passing, ‘the renaissance of native Irish literature’ was recorded:

If any lady of the Irish land could be Irish of the Irish she was. A Celtic student of no mean attainments herself, she was her husband’s and Eugene O’Curry’s fellow worker in the great movement of the renaissance of native Irish literature and the critical, as well as the popular, study of the Irish language. Her husband was a student who, beyond his connection with the Young Ireland movement, took little interest in politics. He felt his mission to be to aid in convincing the world that his race had a civilised history to boast of. Mrs O’Donovan impressed upon her sons with the enthusiasm and the culture of an educated Irish mother that they were the children of an ancient nation which had a future. Mrs O’Donovan was affectionately attached to her children but never when they were required at any point of danger in their country’s cause did she ask them to remain with her. She was proud of their courage and their achievements.[41]

__________________

[1] Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p108. ‘When Lieutenant Thomas Larcom was sent to Ireland to direct the Ordnance Survey and found that his life would be chiefly spent in this country, it occurred to him as a natural and necessary thing to learn the Irish language. Strolling down O’Connell Street shortly after his arrival, he read over the door of a large house the inscription, ‘The Irish Society’ and he walked inside. Nobody was in the hall and he ascended the stairs, pushed open a door that he saw before him, and found himself in a room where a number of gentlemen were seated round a table. He apologised for his intrusion but added that he desired to learn Irish. The astonished committee of the Irish Society explained that their purpose was not the instruction of the English-speaking in Irish but one of them said he could recommend the lieutenant a qualified teacher who was however only imperfectly acquainted with English – a young man named John O’Donovan’ (Dublin Evening Telegraph, 1 May 1920). [2] For all Thomas O’Conor (Tomás Ó Conchúir) left to Irish history, biographical detail is limited. John O’Donovan first met O’Conor at Carrickmacross in 1835 and recommended him for employment. He was evidently native of that place (barony of Farney, Co Monaghan), and then aged 23, single, working as a hedge schoolmaster – one of the best Latin, Greek and Irish scholars O’Donovan had met for a long time. In June 1838, George Petrie, in a letter to John O’Donovan, praised the work of O’Conor: ‘O’Conor has written an excellent letter on the old Church of Kill-cummin. It is a genuine specimen of the ould stock’ (The Life and Labours in the Art and Archaeology of George Petrie (1868) by William Stokes MD, p191). In July 1840, Eugene O’Curry wrote to O’Donovan, ‘O’Conor was all last month anxious to be sent to the country, but now he complains of want of money & I fear he is not going on well – that he drinks and acts the fool with his money and his time. However if you want him out you ought to write to Mr Larcom on the subject, but without hinting to him, or to any body else, what I say’ (Ordnance Survey Letters Limerick (2014) Edited by Michael Herity, pxi). O’Conor was described as ‘ravaged by tuberculosis' (ibid, xiii). Evidently O’Donovan did not want him out for the two men were working together in Kerry in 1841. O’Conor’s career after this date however is open to research, but it seems he ‘died early, and without having given more than a promise of taking a high place amongst those who have made Irish history and antiquities their peculiar study’ (‘The Ordnance Survey letters of King’s County/County Offaly: their place in the historical literature of the county’ by Michael Byrne, Offaly Heritage 7 (2013) pp78-118). Other unsung heroes of the Ordnance Survey at this period include ‘a corporal of the Royal Sappers and Miners’ who died in the Fever Hospital, Killarney, regretted by, among others, ‘the civilians employed on the Ordnance Survey’ (Kerry Examiner, 7 December 1841) and ‘an extraordinary’ eight-year-old boy from Derry named Alexander Owin (or Gwin) who, working under the superintendence of Capt Stotherd, Royal Engineers, had by rote ‘the fractional logarithms from 1 to 1000. His rapidity and correctness in the various calculations of Trigonometrical distances, triangles, &c, are amazing beyond any thing we have ever witnessed. He can, in less than one minute, make a return in acres, roods, perches &c of any quantity of land’ (Tuam Herald, 30 October 1841). [3] Or Ballincushlane. O’Conor covered Dysert on 7th September, while O’Donovan researched Brosna, Currans, Killeentierna and Nohoval on 9th September. O’Donovan had reported on O’Brennan and Ballymacelligott, the other two parishes of Trughanacmy, on 29th July and 30th July 1841 respectively. A description of Trughanacmy is given here http://www.odonohoearchive.com/baronies-and-civil-parishes/ and this link http://www.odonohoearchive.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IE-MOD-4.4.pdf. provides detail of land divisions. [4] ‘O’Donovan and others of the staff, during the summer months, proceeded to these localities, inspected the existing remains of monuments, learned from the old Irish speaking people the vernacular name of each town-land, and carefully noted down all the local traditions and legends ... since obliterated by famine, eviction and emigration ... The energy, scholarship, and acumen, exhibited by O’Donovan throughout these labours made a remarkable impression on all those with whom he came into contact’ (On the Life and Labours of John O’Donovan (1862).pp8-9). [5] Newry Reporter, 16 December 1911 reproduced from the Down Recorder. The question was raised following an account of the letters which appeared in the Irish Builder and Engineer of that year (issues 19 and 24). [6] ‘After the appearance of the Memoir of Londonderry, the first county to be surveyed, the Treasury began to raise difficulties, and finally the work was stopped. Then, the Royal Irish Academy approached the Lord Lieutenant, and mainly through the efforts of Lord Adare, afterwards Lord Dunraven, a Commission was appointed and sat in 1843. After hearing evidence at great length, Petrie, Dr Todd, the Rev Dr Robinson, and Sir Thomas Larcom being amongst the chief witnesses, the Commission recommended the resumption of the work under Petrie, and made a number of valuable suggestions which unhappily bore no fruit. Next year in the estimates no notice whatever was taken of the recommendations of the Commission. All its labours went for naught. The vast stores of the unpublished information so laboriously collected from almost every county, carefully classified, corrected and indexed, were deposited in Mountjoy barracks’ (Newry Reporter, 16 December 1911). [7] Newry Reporter, 16 December 1911. ‘In acknowledging the gift, the Academy described it as ‘the most valuable accession ever made to their library,’ and expressed the hope and expectation that ‘scholars engaged in historical and topographical studies will largely avail themselves of the materials thus liberally placed within their reach.’ This expectation has been imperfectly realised. Means may yet be found for making better known to Irishmen of culture this treasure house of information.’ [8] https://www.ria.ie/. [9] Professor Michael Herity (1929-2016) had ambitions to write a definitive biography of O’Donovan. His editions of the Ordnance Survey letters covered an astonishing twenty-five counties: Ordnance Survey Letters Donegal (2000) Ordnance Survey Letters Meath (2001) Ordnance Survey Letters Down (2001) Ordnance Survey Letters Dublin (2001) Ordnance Survey Letters Kildare (2002) Ordnance Survey Letters Kilkenny (2003) Ordnance Survey Letters Laois (2008) Ordnance Survey Letters Offaly (2008) Ordnance Survey Letters Mayo (2009) Ordnance Survey Letters Galway (2009) Ordnance Survey Letters Sligo (2010) Ordnance Survey Letters Roscommon (2010) Ordnance Survey Letters Longford and Westmeath (2011) Ordnance Survey Letters Londonderry, Fermanagh, Armagh, Monaghan, Louth, Cavan, Leitrim (2012) Ordnance Survey Letters Wicklow and Carlow (2013) Ordnance Survey Letters Wexford (2014) Ordnance Survey Letters Limerick (2014). Other editions include Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Clare (1928) by Michael O’Flanagan and The Ordnance Survey Letters Wicklow (2000) by Christiaan Corlett and John Medlycott. [10] Waterford News, 20 December 1861 reproduced from the Kilkenny Moderator. See note 26 regarding O’Donovan’s ancestry. [11] This year of birth was given by Dr John O’Donovan. It is now generally believed that the year of birth was 1806. However, it is worth noting that it was not uncommon practice to name a child again the same as a lost infant, as was the case in Donovan’s own children. See note 27 regarding O’Donovan’s deceased children: he went on to name another two of his sons Edmond and Henry. [12] ‘John O'Donovan's Last Illness’ by Michael Herity, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol 137 (2007), pp131-145. [13] Waterford News, 20 December 1861. Reproduced from the Kilkenny Moderator. ‘O’Donovan’s connection with the Survey originated, we believe, under the following circumstances. Lieutenant Larcom, having determined to acquire sufficient knowledge of the Irish language to enable him to have the apparently strange local names correctly engraved on the maps, applied to Mr George Smith, the well known Ordnance publisher, to find him a competent instructor. Smith consulted James Hardiman, who brought forward John O’Donovan, and the latter was at once engaged to teach Irish to Lieutenant Larcom, by whom his great scholarly capacities were soon recognised ’ (Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p108). Larcom’s version of the means of their introduction is given in note 1. [14] ‘In 1830, Petrie was fortunate enough to acquire an autograph copy of the Annals of Ireland by the Four Masters extending from the year 1172 to 1616 which manuscript he generously transferred to the Library of the Royal Irish Academy. The chronology and topography embodied in this work having been found invaluable by the historical department of the Survey, O’Donovan in 1832 commenced to translate it into English and completed the task in the ensuing year’ (Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, pp108-110). [15] Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p111. [16] Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p111. [17] ‘John O'Donovan's Last Illness’ by Michael Herity, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol 137 (2007), pp131-145. [18] Freeman’s Journal, 19 December 1861. [19] For a detailed account of John O’Donovan’s final days, see ‘John O'Donovan's Last Illness’ by Michael Herity, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol 137 (2007), pp131-145. [20] Dr Charles Graves had applied to the Cemetery Committee of Glasnevin requesting a free grant of ground for O’Donovan’s interment due to the deceased’s financial circumstances; it was readily agreed to (Freeman’s Journal, 18 December 1861). [21] Subscriptions received by Edward Clibborn Esq, Royal Academy House, Dawson Street Dublin. A list of subscribers is given in On the Life and Labours of John O’Donovan (1862). [22] Irish Examiner, 14 December 1861. A detailed biography of Dr John O’Donovan (Seán Ó Donnabháin) by Diarmaid Ó Cáthain is contained in the Dictionary of Irish Biography. [23] Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p113-4. [24] Tribute in Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine (1862) Vol I, pp106-114. It was published earlier in the Evening Freeman, 28 December 1861. See also remarks on O’Donovan’s writings in Literary Notice of ‘The Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History’ in Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine (1861) Vol III, pp290-294. [25] ‘Recollections of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa,’ The Irishman, 21 June 1879. In the same letter, O’Donovan accepted Rossa’s invitation to Skibbereen, and confirmed that he was not a Protestant – ‘I had not the honour of having one Protestant ancestor from 1817 to 493 when St Patrick cursed an ancestor Lonan in the plain of Hy-Figente.’ O’Donovan soon after visited Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa at Skibbereen and went to see the braon-sinshir at Castle Donovan, Drimoleague. He also called on Morgan O’Donovan of Montpelier, Douglas, Cork (Evening Echo, 29 September 1961). [26] O’Donovan listed the reasons for his concern: ‘1. Castle Donovan was forfeited in 1641 and given away forever; 2. My ancestor Edmond killed the son of O’Sullivan Beare and was killed himself in 1643 leaving his descendants landless; 3. The race of Colonel Daniel O’Donovan became extinct in 1829 in the person of General Richard O’Donovan who left the small remains of his patrimonial inheritance to Powell, a Welshman; 4. The present O’Donovan is childless. His brother Henry has one daughter who if she be the only heir will leave the name landless. These four reasons adding to them your imprisonment in 1859 convinces me that the curse of the good Coarb still hangs over us all’ (The Irishman, 21 June 1879). A writer in Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine (January 1862) described O’Donovan’s distinguished ancestry as a branch of the Munster clan styled by old native writers Ui Figeinte or Sons of the Woodman who claimed descent from Owen, ‘The Splendid,’ king of the southern half of Ireland in the second century: ‘The tribe name Ui Figeinte is said to have originated in the fourth century from a soubriquet given to their chief Fiacha, seventh in descent from King Owen. The head of the clan, towards the close of the ninth century, rendered himself conspicuous by his determined opposition to Brian Boru; and from him, who was styled Donndubhan or Donovan, signifying literally the black-haired or black-complexioned chieftain, the tribe took the name of Ui Donnabhain, or descendants of Donovan.’ One Edmond, the son of O’Donnell O’Donovan, chief of his name, of Bawnlahan, near Glanmore Harbour, in the county of Cork, quarrelled with the O’Sullivans about the boundary between the territories of Clancahil and Bantry: ‘About the year 1616, Edmond, son of Donnell O’Donovan of Banlahan, county Cork, slew the eldest son of O’Sullivan, chief of Beare, in a dispute which occurred relative to the boundaries of their respective lands. To escape the vengeance of the O’Sullivans, Edmond O’Donovan fled to Leinster, where he found an asylum in Kilkenny with William FitzWalter Burke of Gall, of Gaulstown, descended from the Red Earl of Ulster, whose grandfather, Walter Gaul Burke, had been one of the two knights representing the county of Kilkenny in Parliament in the year 1560. His daughter, Catherine Gall Burke, subsequently became Edmond’s wife’ (Duffy’s Hibernian Magazine, January 1862, p107 and Waterford News, 20 December 1861 reproduced from the Kilkenny Moderator). Edmond’s father, ‘accompanied by fourteen of the gentlemen of Carberry,’ went to Gaulstown to bring his son home but found the marriage had taken place, ‘and this being the period of the first outbreak of the troubles of 1641, Edmond told his father that he would not go home, but would remain with his father-in-law till he would see what the issue of the wars would be; and his father and friends, who promised him that a perfect reconciliation had been brought about between the O’Donovan and the O’Sullivan Beare, were obliged to return home to Carberry without him.’ He settled with his wife and children in Ballinlaw Castle on the estate of his father-in-law where he lived till 1643, when both he and Gaul Burke, having joined the army of the Confederate Catholics under General Preston, were both slain in Ormonde’s victory over the Confederate forces at Ballinvegga, about four miles northward of New Ross. The downfall of the family was thus sealed: Doctor O’Donovan was the sixth in descent from the Edmond who fled to Kilkenny from Cork and was killed at Ballinvegga, and the property of Gaul Burke having been confiscated by Cromwell, and granted away to George Bishop, who was secured in the estates by the Acts of Settlement [1662] and Explanation [1665], both the Burkes and O’Donovans descended into mere tillers of the soil which their forefathers had held in fee. Genealogy https://gw.geneanet.org/gbgen4?lang=en&v=O%27DONOVAN&m=N [27] The names of O’Donovan’s sons who died in infancy were Edmond O’Donovan (1840-1842), Henry O’Donovan (1850-1851) and Morgan Arthur O’Connor O’Donovan (1858-1860). My thanks to Marie Huxtable Wilson of Tralee for assistance with genealogy. It is observed in the latter record of 1858 that the name of the child's father was taken down as Francis. [28] Crean townland is in the parish of Killokennedy. My thanks to Peter Beirne, Clare County Library, for assistance in identifying ‘Glenview.’ The property is recorded in Houses of Clare (1999) by Hugh W L Weir. In 1999, the eighteenth century one-storey five-bay residence was standing but uninhabited. Its condition today is ruined, the building having suffered a fire. [29] Decies, Journal of the Waterford Archaeological & Historical Society, No 64 (2008) p177. [30] Kilmarnock Herald, 4 March 1910. Four illustrations of the Orion by various contributors appeared in the Illustrated London News, 29 June 1850. As Edmond O’Donovan was only two years old at this time, this story almost certainly applies to his brother John. The steamship Orion, a packet ship carrying the mails between Portpatrick and Donaghadee, was built in 1847. It sank about 150 yards off Portpatrick Lighthouse on 18 June 1850 with the loss of 41 lives. The incident was described in The Wreck of the Orion, a Tribute of Gratitude (1851) by Rev Joseph Clarke, a survivor. William Howie Wyle (1833-1891) was a Scottish journalist and Baptist minister who in 1850 was sub-editor of the Ayr Advertiser. [31] New Ross Standard, 8 February 1935. Further reference to the campaign in With Hicks Pasha In The Soudan: Being An Account Of The Senaar Campaign In 1883 (1884) by John Colborne. [32] Framlingham Weekly News, 4 August 1888. [33] Published in Decies, Journal of the Waterford Archaeological & Historical Society, No 64 (2008) pp175-204. See also Soldiers of Destiny: A Study of Fenianism 1858-1908 (2018) by the same author, and Clare, History and Society (2008) Edited by Matthew Lynch and Patrick Nugent for further reference to Broughtons and O’Donovans. Information courtesy Peter Beirne, Clare County Library. [34] Flag of Ireland, 5 January 1884. [35] ‘Notes and Queries John O’Donovan’s Family,’ The Irish Book Lover, April 1943, p17. Reference courtesy Peter Beirne, Clare County Library, who observes that volume XXVII (Jan 1940-Feb 1941) of the same publication also carries contributions on the O’Donovan family (pp161, 179 and 207). [36] The Star, 28 July 1874. [37] Bradford Observer, 25 July 1874 (originally published in the London Times). ‘Mr O’Donovan owes his release to the kind offices of Mr Furley, a member of the Red Cross Society of Great Britain, who has earned much esteem and gratitude from the Carlists by the way in which he has devoted himself and his money to the relief and assistance of the wounded.’ Henry’s letter in full: ‘Your letter, dated Saturday, came to hand this morning. I presume it was written last Saturday week, and has been lying at the Post Restante, Saint Jean de Lux, until forwarded to me by a person to whom I enclosed a stamped envelope for the purpose. By the way, I have fixed my quarters here since Sunday last, having secured a nice chambre garnie. Here I must remain for a while as I feel too ill to move. You are lucky in not having gone searching for me at Estella, as it is more than probable that you would only have succeeded in getting into the lock-up too and let me tell you that, however extensive your prison experience might be, you could scarcely have come across anything like the Carcel of Estella. Six whole months have I been immured in that Bastille, which is as bad as anything I have heard of the Black Hole of Calcutta, and nothing but a constitution endowed with an incredible power of resistance could have brought me out alive. Imagine yourself sleeping for two months on freezing tiles in the depth of winter without even an overcoat to cover you, and rising in the morning – c’est a dire if you were able – with every joint made stiff by cold and rheumatics. At the end of that time a little straw was distributed among the prisoners – so little, indeed, that all I could do out of my lot was to improvise a pillow. The food, too, was as bad as it could be, and so limited in quantity that it barely sufficed to support life. Twice a day was the wretched pittance served out, consisting of half an ounce of garbanzos (common chick peas), with a few spoonfuls of hot salty water and a piece of black bread about the size of your fist, which to the bite felt like a lump of baked clay. Such, for months, was the sustenance accorded to us unfortunates. At length, towards the end of February, my health completely gave way. Though I lay for four days, gradually becoming unconscious, being at last unable to lift my arm or turn from one side to the other, then, and not till then, the chief gaoler, finding that I could not be roused from the comatose state I was in, sent for a military surgeon, who got me carried to the hospital in a litter. But a peculiarly disagreeable circumstance had occurred during my lethargy. The prison being literally invaded by myriads of lice, fleas, bugs, and ants, it was absolutely necessary in order to secure any sleep at night, to subject my garments during an hour at least every day to a rigid inspection and detergent process. The ears, too, had to be plugged with chewed paper to prevent the indefatigable tormentors from entering by that portal, wherein they often sufficiently annoyed me. During the long period, however, that I remained insensible legions upon legions of parasites had concentrated their attacks upon my devoted carcase; they actually burrowed into the flesh and increased so that they spread purulent ulcers, in which they buried themselves, and from which they could only be dislodged by the plentiful application of soft soap in a warm bath followed by sponging the surface with a solution of carbolic acid. I think, however, I have said enough of these matters to give you a faint idea of what I have gone through – indeed, even this recital may by no means be enlivening to you. The immediate cause of my arrest was that, having left a small vial of laudanum which I was in the habit of using to procure sleep upon my dressing table, the padre cara in whose house I was billeted asked me what it was. I told him that it was a preparation of opium, and also the use to which I applied it, whereupon the old rascal, without pretending anything, secretly intimated to the authorities that I was carrying poison, doubtless with some illegitimate intent. Whereupon your old comrade, Dufour, captain in the Carlist troops, also came and attacked me. They immediately conducted me to Elizondo, where the Junta of Navarre solemnly accused me of being an emissary of the Ronda Secreta of Madrid. What the Ronda Secreta may be I do not exactly know, but believe it is a society of the Intransigentes, whose object is the disposing of aspirants to the Spanish Monarchy. You may be able to form some idea of my astonishment when I was coolly told that there was no doubt that I was an assassin charged with the intended poisoning of Carlos VII. One witty gentleman asked me ironically how my friend Contreras was, and when I had last seen Pablo Anglo; whoever the latter person may be I am sure I cannot say, nor can I recollect ever having had the pleasure of meeting any person of that name. My utter ignorance of the existence of any such conspiracy being attributed to a determination not to divulge the names of my accomplices, I was sent to Estella to be disposed of by the military authorities, and there I remained until a fortnight ago.’ This episode was described in detail in Among the Carlists (1876) by John Furley. [38] Oko Jumbo (1798-1891) chief in the Kingdom of Bonny, Nigeria; son of a slave who had amassed great wealth and power as a result of astute trading. A number of Oko Jumbo’s sons were educated in England including his eldest son, Prince John, educated at Liverpool College (principal Canon Butler) where he was known as ‘the African Prince.’ John Jumbo received a sword of honour from the Secretary of State for the Colonies, inscribed, ‘Presented to Mr John Jumbo for his gallant and faithful services in the war against the Ashantees 1883.’ John Jumbo died at sea on 25 February 1886 from apoplexy on board the steamer Benin bound for Liverpool from the West Coast of Africa. He was returning to England to stay with his wife (Elizabeth Gwynne Williams, who he married in 1879) and daughter at Mersey Road, Rock Ferry. Oko Jumbo’s third son was Herbert Fubarawari Oko Jumbo. He was a Freemason, admitted to the Order (Royal Victoria Lodge No 1013 Liverpool) in 1885. Herbert Jumbo died in his palace on Monday 28th July 1933, mourned by the ibani kingdom, and was buried at Burukiri, Bonny. Other sons were named as James, William and Cecil. In early January 1892, one of Oko Jumbo’s sons was on board the Matadi captained by John T Walsh RNR from Liverpool bound for Africa. On board was J W Carter, proprietor of the Royalty Theatre, Chester, who, in an account of the journey, made the following remark: ‘During the afternoon in the smoking room, I made the acquaintance of a young African who was returning home after spending six years at one of our principal London colleges. His father is a well-known chief, Oko Jumbo, on the West Coast of Africa, a large dealer in palm oil, nuts, and other native produce. His son’s reason for being educated in England was to enable him to understand the English side of bargaining, as their deals consist simply of exchanging goods, very little, if any, money ever changing hands. His constant study on board was the English dictionary’ (Cheshire Observer, 30 January 1892). A little later in the same month, Cecil Jumbo arrived on the African Company’s steamer Dahomey to begin his education in England. He was 19 years old. In 1885, 87-year-old Oko Jumbo first visited England. He was described as the protégé of the African merchants, Messrs Thomas Harrison and Company of Liverpool. News of the death of Oko Jumbo was received in England in August 1891. He was interred at the Missionary burial-ground at Bonny. In 1892, Dan Jumbo was ruling in Bonny. [39] John O’Donovan (1806-1861): A Biography (1987) by Patricia Boyne. Sincere thanks to John Kirwan, Kilkenny Archives, for bringing this work to my attention. [40] The UK Census of 1901 records one Henry O’Donovan, pauper, in the Salford Union Infirmary. He was aged 47, Dublin born, and his occupation was given as journalist author. Henry Donovan (sic) was admitted to the North Riding Lunatic Asylum, Clifton, York, from St John of God Hospital, Scorton (founded in Scorton, North Yorkshire in 1880 by the Brothers of the French Province of the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of God for ‘unwanted people, ‘cripples and incurables’). Henry died in North Riding Lunatic Asylum a few months later on 23 September 1905. His next of kin was his brother, Richard, then of Woodbine Cottage, New Brighton, Cheshire (reference courtesy Lydia Dean, Archives Assistant, Borthwick Institute for Archives, York). Henry O’Donovan’s burial recorded at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126612375/henry-o'donovan/photo. Genealogical and other related research for this note courtesy Marie Huxtable Wilson, Tralee and Amanda Todd (AradiaB), Yorkshire. [41] Irish Independent, 13 June 1893. The death of Mrs O’Donovan, at Broadford, was reported in August 1871 but was subsequently retracted, for ‘Mrs O’Donovan continued to enjoy excellent health.’