’Twas sad the day I sailed away from my little Irish home To this land of mountain majesty where I wandered far alone … And when I leave this world behind I ask you Lord to, please, Put a little bit of Ireland in Your heavenly plan for me.

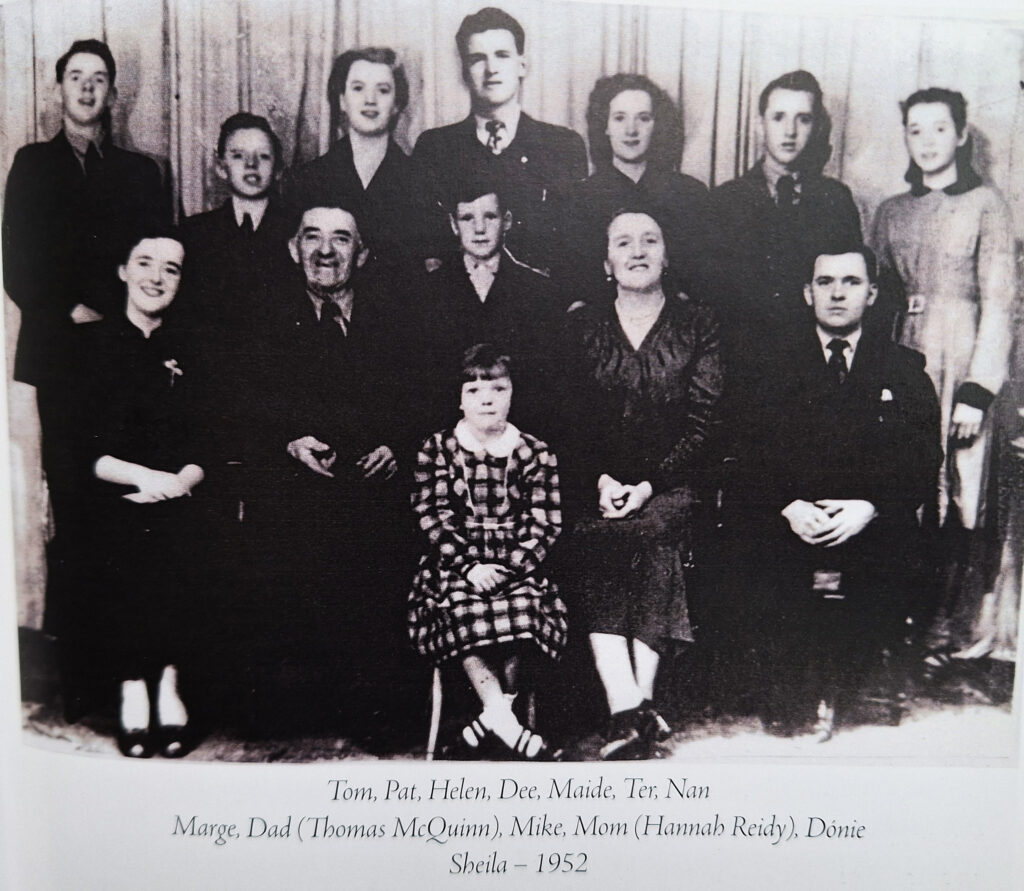

Maida McQuinn-Sugrue was born into a farming family at Fiddane, Ballymacelligott, Co Kerry in 1933, one of eleven children of Thomas McQuinn and Hannah Reidy. In 1952, at age 19, she emigrated to America and now, after 70 years in the States, recalls her life in an illustrated memoir, Gramma Tell the Story.[1]

Maida’s first job was at the age of four washing eggs to be sold by her mother (and dropping one!). She later progressed to minding siblings and milking cows, ‘all of us who were able and old enough helped in the fields and in the house.’ Her childhood memories at Fiddane – a townland situated midway between Castleisland and Tralee – include minding turkeys, days in the bog cutting turf, threshing days cooking rutabaga (American for bacon and cabbage), and the fun of being part of a large loving family.

Maida was christened Mary but named after Maida Vale of Scotland at the suggestion of the midwife. Maida often wondered about her unusual name and researched its origins, secretly hoping ‘it might be a woman of some greatness or royalty.’[2]

Maida had a great love of music and learned to play the fiddle, taking lessons from Padraig O’Keeffe. Her mother saved the butter paper, cleaned and dried it, so Padraig had material on which to write his notation.

Her first four or five years of schooling were not joyful and Maida describes how she ran for home one day only to be caught and returned, ‘In the 1930s, teachers had the right to more severe forms of punishments.’ Fortunately, Maida was enrolled in a school closer to home where her new teacher ‘shouted more than she slapped.’

When Maida was fourteen years old, some recruiting nuns from a German Order in London came to her school. Maida decided to join, and a long road journey and unpleasant sea voyage followed. In London, she felt like ‘a lost bird flown into the house.’ After one year, she went home on holiday and never returned.

Maida completed her education in the secondary school in Castleisland and ‘was glad to be done with that part of my life.’ She believes she developed a bad taste for learning after her unhappy early years in school.

A job in a grocery shop in Dublin enabled funds for a voice teacher but it was short-lived as the shop went broke. Back at home in Fiddane, Maida returned to farm work but over in Chicago, a man named Dan Russell, who had emigrated from Fiddane thirty years earlier, was running a weekly Irish dance. Word came that he was prepared to sponsor any in the family who wanted to go there. Maida jumped at the chance and a huge party was thrown by friend and neighbour, Charlie Lenihan amid ‘much weeping as they all in turn said their goodbyes to me.’

RMS Franconia (‘the bathroom ship’), a liner being used to bring soldiers home from Europe after the Second World War, was mode of transport, sailing from Cobh to New York. The first five days of the voyage Maida spent in her cabin with sea-sickness, but ‘it was an amazing sight to see the Statue of Liberty with open arms to welcome us.’

In New York Maida was shown Brooklyn Bridge which her grandfather, Dan McQuinn, had helped to build.

On arrival at the station in Chicago, Maida found herself ahead of time as she had boarded a fast train, but in a strange new world, did not know how to make a phone call in the Travellers’ Aid booth to let the Russell family know! After settling in with her host family, homesickness set in, ‘I spent hours putting pen to paper, and, between tears, writing the first letter home.’

Maida went to work for Sears Roebuck, sorting internal mail, but not too long after, she was hospitalised with appendicitis and landed with a hefty bill. The Irish community took up a collection at the weekly dance which helped to pay off most of the debt.

’Tisn’t Bad

Maida’s love of music brought her into contact with like minds and soon she was performing on a weekly Irish show – the Jack Hagerty Program.[3] As she became known, she was asked to sing elsewhere, appearing at one stage with Englebert Humperdinck who was then making his way in the music business. She also played for a youthful Michael Flatley and his brother Patrick as well as with native players like Cuz (Terence) Teahan.

In 1953, Maida met Caherciveen native, Denny Sugrue, and they married in 1955. One afternoon Maida wrote a song, An Irish Country Girl, and sang it to her husband who said, ‘Tisn’t bad.’ The Bonnie Bride followed. News of strife back home in Ireland inspired Peace Depends on You. A Shannon River Breeze was her next composition, and over the course of the following year, she recorded her songs on a record at her own expense.

Newlyweds Maida and Denny, settled in a new rented apartment, were enjoying married life. Denny had worked at Larkin’s Bakery, Milltown before he emigrated and one day the couple hunted down ingredients and baked a large batch of barmbrack. Denny continued to make batches for the next forty years. Parenthood would occupy the coming years as four children, one girl and three boys, followed in quick succession. Indeed, the family photographs in Gramma Tell the Story do so very well.

When Maida’s parents retired from farming at Fiddane, they each made a ‘trip of a lifetime’ to Chicago. Of Maida’s many visits home to Ireland, she writes, ‘Even after all the years coming and going, I always find it heart-wrenching as the plane lifts off – as if taken by force from my country I have loved and always call Home.’

Gramma Tell the Story is available at https://www.amazon.com/Gramma-Tell-Story-Maida-McQuinn-Sugrue/dp/1956823182.

____________________

[1] Gramma Tell the Story (2022) Joshua Tree Publishing, 154 pages plus front matter. Copy held in Castleisland District Heritage, Reference IE CDH 193. [2] It might interest Maida to know that the great Sir Walter Scott wrote an epitaph for Maida, his favourite pet, who he named after the Battle of Maida of 1806: Maidae Marmoria dormis sub imagine, Maida,/Ante fores domini, sit tibi terra levis. [3] https://www.irishhour.com/history