‘You want the delicate touch of an artist for successful butter making’

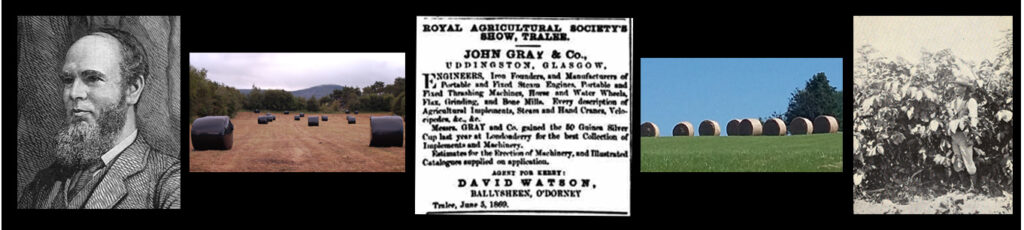

Watson’s Creamery, Castleisland, once occupied a site in Old Chapel Lane. The company was established in Tralee in 1885 though initially with some difficulty:[1]

There is a factory worked at Middleton [Midleton], County Cork, and one at Hospital, County Limerick, where only the new churned butter is bought. An attempt was made to start a factory in Tralee this spring, but purchasers for shares did not come forward.[2]

Some years later, a visitor to the creamery described the butter produced as ‘splendid’:

I indulged my curiosity on Monday by visiting Mr Watson’s Creamery. It was a real pleasure to look at Mr Watson’s dairy-girl going through her work. Mr Watson and his son being busy, she gave me some butter to taste, took me along showing and explaining everything, and still doing her business, so that when Mr Watson did come there was very little left for him to say. I could not help expressing my admiration to Mr Watson who explained that she was trained in the Munster Dairy School. Training is what is wanted for the making of good butter. We can no longer shut our eyes to this fact. If the butter is to be made at home, where it ought to be made, our girls must be trained. The day of the knowledgeable woman is gone.[3]

David Watson had much to say about agricultural affairs. In a memorandum to the Select Committee on Industries (Ireland) on the production of Kerry butter, he remarked on its preparation at home and abroad, as well as climate, competition, carriage, and price.[4]

He was also vocal on ensilage for cattle feed, a process ‘superior to haymaking because it is independent of the weather.’[5] In a letter to the editor of the Kerry Reporter he wrote:

There has now been several years’ trial of silos, and I have never heard of a failure in preserving the grass when sufficient pressure has been put on it; 150lbs to the square foot appears to be necessary to prevent fermentation. What a silo will cost depends much on the facilities the party erecting it may have on the spot. Where an existing out-office can be utilised, that is the right thing to do. Where there is no convertible building some people for economy use timber … Lord Tollemache has built silos for his tenantry in Cheshire … Farmers in Ireland might borrow for the purpose from the Board of Works as I fear without borrowing in some way few could afford to build for themselves after the past five years of bad crops and low prices.[6]

A little is learned about the enterprising David Watson from his great grandson, Kerry’s Eye journalist, Gordon Revington:

David Watson, a Scot, came to Ireland in the late 1850s and leased a farm in Abbeydorney from the Crosbies. He also had a farm outside Dingle. He ran a herd of short-horns but the land he had in O’Dorney was of rather lesser quality than some of the territory in that area. He along with his brother Gerald, was the founder of what became Lee Strand.[7]

On 29 January 1856, David Watson, son of William Watson, farmer, was resident at Ballyeigh, Ballybunion when he was married in the parish church of Killury, to Catherine Clara, daughter of Garrett Pierce, gentleman. Their son, John Watson, recalled his childhood in a letter to the Kerry Reporter in 1927:

I was born on Dec 1st 1856 at a white-washed homestead on the sandbanks of Ballybunion. My father, David Watson, was land agent for Lord Listowel and lived there, afterwards removing to Ballysheen, under Mr Crosbie [William Talbot], farming about 500 acres of very mixed land. My first experience was being sent to Meenogohane to my uncle, Mr Tom Pierce, and attending a school where we paid 1d per week and brought in our own sod of turf for the fire in the winter.[9]

Watson’s role as land agent may have precipitated an attack on his property in 1862:

On 20 February, the out-offices at Ballysheen were maliciously set on fire and burned to the ground, destroying not just the buildings but 15 prime dairy cows, 1 bull, 8 pigs, 1 turnip machine, stall fittings for 24 cows, 1 set of donkey harness, 2 calf troughs, 2 sashes and frames, and 1 grinding stone, in a case of ‘agrarian outrage.’[10]

Catherine Clara Watson died at Ballysheen on 2nd September 1863 after giving birth to her son, David George Watson. She was aged thirty-two.[11] David Watson married again on 28 December 1865 to Jane, eldest daughter of Mr William Petrie, Hotel, Dingle.[12] Sons and at least six daughters were born to them.[13]

David Watson, ‘late of Ballysheen, Abbeydorney and Ballymoreigh, Dingle,’ died at his residence, 5 Clonmore Terrace, Tralee on 9 January 1901 aged 74 years. He was buried in Abbeydorney cemetery.[14]

The business appears to have continued under Gerald Watson until the Tralee creamery was sold to The Tralee Farmers’ Co-operative Society in 1920, thereafter trading as Lee Strand Co-Operative Creamery Ltd, Tralee.[15]

Gerald Watson died at Edinburgh on 24 June 1926 where he was on a visit to his daughter.[16] He was laid to rest in Ballyseedy.[17] The remaining Watson creameries were purchased by the Dairy Disposal Board in 1928.[18]

Kerry Creamery Company, Castleisland

Another early establishment in Castleisland was the Kerry Creamery Company which was founded in about 1891 by J K O’Connor and August Wilhelm Lofmark of Sweden.[19] It was described as ‘perhaps one of the most successful in the South of Ireland, receiving several thousand gallons of milk daily and the butter manufactured there is considered the finest obtainable and commands the highest price in the English and Scotch markets.’[20] A subsidiary was opened in Firies in 1893.

Kerry Creamery Company ran into difficulties during the fever epidemic of 1894 when the proprietors were accused of accepting milk from contaminated homes.[21] However, five years on, their produce was being described as incomparable:

The London papers have made special reference to the splendid butter supplied to the Members of Parliament visiting the South of Ireland. During their stay at the Parknasilla Hotel they were so pleased with the beautiful flavour of the butter that several made enquiries as to where it was manufactured; and the manageress, Miss Quinn, informed them that is was got from the Kerry Creamery Company, Castleisland, of which Mr J K O’Connor is proprietor, who had been supplying the hotel for a considerable time past. The English visitors spoke loudly of the beautiful quality and said that no foreign butter could compare with it.[22]

Creameries in Modern Times

Further reading on this subject, Recollections of the Co-Op Years A Personal Account (2007) by Maurice Colbert[23]; The Government’s Creameries: A history of the Dairy Disposal Company, 1927-1978 (2010) by Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh[24]; Listowel to the Liffey The Kerry Farmers Who Marched in 1966 (2017) by John Roche; Born for Hardship (2019) by John Roche.

____________________

[1] ‘Although David died in 1901, the firm continued to be named David and Gerald Watson. In total they opened 13 creameries throughout mid-Kerry. The firm was purchased by the Dairy Disposal Board in 1928’ (ref The Kerry Creamery Experience, Listry). [2] Kerry Evening Post, 19 August 1885. ‘An engine, separator, and butter worker for 60 cows, would cost £150. For a public factory, from £500 upwards, according to the quantity of milk to be separated. Farmers as a rule are shy of joint stock companies, yet I am satisfied if a few factories were established, either through government assistance or by private parties, so that the farmers could see for themselves the advantages of them, they would soon be induced to start themselves, just as they did in the case of steam portable threshing machines, of which there are no less than 16 in this neighbourhood, most of them owned by poor men. A great difficulty with manufacturers of any kind in Ireland is the cost of fuel. Coal has nearly all to be brought from England, and if of a good description, it costs £1 a ton. Turf is also expensive from the amount of labour required to cut and save it. In some districts the bogs have become exhausted, and nothing but refuse remains, but this might be converted into useful fuel by being run through a pug mill, and forced through a mould, like drain tiles or bricks. I know of no industry that ought to succeed in this country so well as a woollen factory if driven by water power. Home-grown wool could be converted into tweed, blankets, flannel, or frieze, instead of being carried to Yorkshire and brought back in webs, paying carriage both ways; there are a few factories of this sort, one lately started in Tralee, and succeeding fairly well I believe.’ [3] Kerry Sentinel, 3 April 1895. ‘As far as I can see, you want the delicate touch of an artist for successful butter making. Why won’t the farmer, who can send his daughter to the Dairy School, send her there? … Though I am not enthusiastic about creameries, I must be just and say that the butter turned out at Mr Watson’s was splendid.’ [4] Memorandum on the Production of Butter in County Kerry, supplied to Sydney Buxton Esq MP, Select Committee on Industries (Ireland) by David Watson of Ballysheen, Tralee and Ballymoreagh, Dingle, Co Kerry. Published in the Kerry Evening Post, 19 August 1885: ‘The production of butter has for many years been a speciality with farmers in the south and west of Ireland, the mild temperature and moist climate being more suitable for that purpose than for corn growing. In the county of Kerry the greater portion of the land is too poor, and the grasses too inferior to fatten cattle, so that the farmers have of necessity had to confine themselves to dairying and rearing stock. During the famine years, 1846 and 1848, the best butter was sold at 70s to 80s per cwt. From that time prices rose steadily until 1876, when 155s per cwt was paid in country markets – double the price now current in 1885. The extremely high prices obtained for a few years gave both farmers and landowners an exaggerated idea of the value of land, an idea of which some of the latter are very unwilling to be disabused. How little even educated men anticipated the great change which a few years has brought round, is shown by the letter of an extensive land agent in reply to one in which I suggested the approach of foreign competition in October 1876. He writes, ‘Canadian butter at 1s 1d per lb must be either of very inferior quality, or arrive in very small quantities indeed; or we would not have had the quotation of 153s per cwt in Tralee the other day. During the last 35 years the average price has risen at the rate of 12s for each 10 years, and it is the opinion of competent judges that there is nothing to check that rate of progress indefinitely. You, no doubt, observe that the steamer with all the cattle from America, went to the bottom, and, without wishing them that fate, I may conclude the possibility of it will deter others from attempting a similar speculation.’ The importation of foreign butter into London is said to have increased by 400,000 packages during the last nine years, whereas Irish butter has become almost unsaleable there, not that Irish butter has become worse, but that foreign butter has become better, and the freight from the continent to London is less than from Ireland to London. The Irish and English railway companies carry fresh butter to London at ½d per lb, the weight of the box or basket not being charged for. The Great Southern and Western Company of Ireland carry 60lbs for 2s 6d but charge the same sum for any lesser quantity. Butter sent by parcels post gets heated and injured through repeated moving. Butterine has become a serious opponent to dairy farmers, the supply is unlimited, it can be manufactured from tallow, lard, inferior butter and oil, and to any shade of colour, and it will keep for a long time with little or no salt. It is made up to imitate French, Dutch or Irish butter and sold from 6d a lb upwards. It is not easy to deal with such competition, especially for the small farmer, with a dairy which was a barn or bedroom from previous winter, with a rent fixed by the Land Commissioners a year ago, and which they now admit to be too high, and with an average taxation of 8s in the £. It would take years before these farmers could provide themselves with suitable dairies, and if they had them, I do not think it would meet the difficulty. Every housewife would have her own opinion about the colour the butter should be, and the quantity of salt to be used, hence arises the want of uniformity, so much complained of by English buyers. I believe with Canon Baggott that the true way to serve the small farmer, and to make really good butter, is to establish butter factories in every parish if possible; if not, then in every barony. There the cream could be separated from the milk, before it had an opportunity of becoming tainted, and then the cream, when matured, could be churned and sent to market in the best and most attractive manner. The farmer would be able to sell his new milk, and the messenger could take back as much skim or butter milk for calf or pig feeding as the farmer might require.’ Full article includes a copy of the proposed County Kerry Butter Factory & Creamery, Tralee, 11 March 1885, in which a public meeting was announced and information given about shares. It was signed by R McCowen jnr, Honorary Secretary. [5] ‘Silage as a food,’ Ballymena Advertiser, 16 April 1892. A letter from J A Gordon, manager of a farm for Nathaniel Buckley Esq, and written from the Estate Office, Galtee Castle, Mitchelstown, Co Cork, on 16 February 1888 gave instructions on how to make ‘sweet silage’ (Kerry Evening Post, 14 March 1888). The process of silage making is said to date back to 1500 BC: ‘The Greeks and Egyptians were familiar with ensiling as a technique for storing fodder as far back as 1000 to 1500 BC. In parts of Northern Europe grass was being ensiled in the early 18th century but it was not until the latter part of the 19th century that it became more widespread’ (uk.ecosyl.com). [6] News article (undated) courtesy Gordon Revington by email. It would appear from internal evidence to date to 1884/1885. The letter in full: ‘Dear Sir – I have read Mr J White Leahy’s letter on winter dairying in your issue of last Saturday. There can be little doubt Mr Leahy is right in recommending ensilage as the best and cheapest winter food for a milking cow. When turnips are used no process that I am aware of, and I have tried a good many, will effectually rid the milk and butter of the disagreeable turnipy flavour. There are no doubt many other descriptions of food that will not affect the taste but to have full milk, and also keep the cow in condition, oil cake, Indian meal, crushed oats, or such like, should be used, and the extra expense runs away with the profit except in the neighbourhood of a town where the milk can be sold. There has now been several years trial of silos, and I have never heard of a failure in preserving the grass when sufficient pressure has been put on it; 150lbs to the square foot appears to be necessary to prevent fermentation. What a silo will cost depends much on the facilities the party erecting it may have on the spot. Where an existing out-office can be utilised, that is the right thing to do. Where there is no convertible building some people for economy use timber. A Mr Blunt of Leicestershire recommends in the North British Agriculturist large casks eight foot in diameter made of redpine partly sunk in the ground, and weighted with levers. For my part, I would prefer a more permanent erection. Lord Tollemache has built silos for his tenantry in Cheshire and if, after a trial, they find them advantageous, he is to charge five per cent on the outlay. Farmers in Ireland might borrow for the purpose from the Board of Works as I fear without borrowing in some way few could afford to build for themselves after the past five years of bad crops and low prices. As far as North Kerry farmers are concerned, I do not agree with Mr Leahy that they are slow to adopt new systems of management, and I refer him to the Seedsmen and implement makers of Tralee whether an extraordinary business was not done in the best implements and machinery, including dairy appliances, during the good years previous to 1879. There are a dozen portable steam threshing machines in the Barony of Clanmaurice alone which surely speaks well for the enterprise of the farmers, especially as it is some of the highest rented land in Great Britain, taking into account its backward situation, wet climate, and poor soil. Small farmers as a rule have bad dairies; the barn or a spare bedroom is cleared out to be used for the summer. It is either musty or smoky. The cream adopts the smell at once, and the question of quality is settled, to the surprise and disappointment of the farmer and his better-half, who are so accustomed to close rooms and turf smoke they do not know that their very clothes smell of it. A cream separator would render the setting of the milk in pans, and its exposure to taint from smoke unnecessary, but separators are expensive articles, much more so than they ought to be, for there is neither material nor workmanship for the £10 or £50 they cost. Then they require steam or water power to drive them, consequently they are beyond the reach of most farmers. They could only benefit by this system through having a butter factory within reach where they could send their new milk, and after the cream had been separated, take home the skim milk to feed the calves and pigs. Very truly yours, David Watson.’ ‘A little salt-petre dissolved in warm water and mixed with the cream taken from milk with a turnipy flavour entirely eradicates it in the course of churning’ (North British Agriculturist, 6 October 1852). [7] Gordon Revington by email 24 June 2022. David Watson’s address in 1860 was Lismaurice, O’Dorney. [8] In 1892, Matsudaira was said to be a student of Oxford for five years during which period his father had died. However, a notice in the Western Gazette of 21 August 1891 stated that Marquis Y Matsudaira was a student at the Agricultural College, Cirencester. Matsudaira Yasutaka entered the Royal Agricultural College in May 1889. After he returned to Japan he founded the private Matsudaira Agricultural Experimental Station, Old Castle, Fukui Prefecture in May 1893. He wrote a paper, The Culture of Kaki [Yorikatzu Matsudaira] which he exhibited at the British-Japan Exposition in London in 1910 (ref: Archival Research on Agricultural Chemistry at the end of 19th century England and Japan Based on Findings at the Royal Agricultural College, Dr Eriko Kumazawa (2010).) See ‘Echizen Matsudaira Yasutaka’s Agricultural Study in England and the Foundation of Matsudaira Experimental Station,’ Bulletin of the Society for Japanese Local History of Education (2013) by Eriko Kumazawa. The photograph of Matsudaira Experiment Station was published in Three New Plant Introductions from Japan (1903) by David G Fairchild. [9] ‘Old Times in Kerry’ by John Watson, Kimberley, South Africa, Kerry Reporter, 1 October 1927. The letter continued: ‘My grandmother, Mrs Pierce of Meenogohane was Dr Church of Listowel’s sister. They both lived to a great age and are buried in the family vault in Listowel graveyard. My mother lies there and my father is buried at Abbeydorney … At Ardfert, where I was married to Laura Petrie of Dingle by the Rev Mr Robert Crosbie Wade, many changes have taken place.’ John Watson of Workington, Cumberland married Laura Petrie, daughter of William Petrie, in Ardfert on 28 February 1884. John Watson also included a strange tale about rising from the dead in his letter, ‘Old Times in Kerry’ (above referenced). It is related here: ‘Many years ago in Dingle there was a case which excited everyone. It was a case of suspended animation which occurred to the supposed dead wife of the Rev Mr Goodman. She had two very valuable rings on her fingers which could not be pulled off before being put in the coffin. So she was buried with them on, in a vault at Raheenyhooig, Burnham. During the night two men entered the vault, prized the lid off the coffin and finding they could not get the rings off either, began to cut off her fingers which caused a circulation of blood and brought her to life again. They got such a fright they cleared off, while she walked home in her grave clothes to her husband – living many years after and bearing him several children. Many such cases have occurred, and to make doubly sure doctors now lance a vein in the arm.’ There were two rectors by the name of Goodman serving the parish of Dingle in the nineteenth century. John Goodman (1756-1839), son of Thomas Goodman, married Jane, daughter of George Chute and Flora Herbert. They had issue a son, Thomas Chute Goodman, c1795. Thomas Chute Goodman served Dingle until his death in 1864. He married in 1824 to Mary, daughter of James Gorham Esq of Ardee, Co Kerry by his wife, Arabella, daughter of Eusebius Chute Esq of O’Brennan, Co Kerry (Arabella Gorham died at Tralee in January 1810 aged 28 years). Note: Eusebius Chute Esq of O’Brennan married Agnes, youngest daughter of George Herbert Esq (eldest son of Arthur Herbert and Mary Bastable) and Jane, daughter of Maurice Fitzgerald, 14th Knight of Kerry. [10] Kerry Evening Post, 22 February and 16 July 1862. David Watson was awarded £185 compensation. [11] Gordon Revington, by email dated 24 July 2022, advises that ‘David George was the third son, John being the eldest.’ [12] The ceremony was performed in Dingle by Rev John L Chute, rector, assisted by Worshipful Chancellor Swindall. [13] Their known daughters were Helen Watson, born 3 November 1866; Lucy Watson, who married in Chicago on 27 September 1883 to Robert Saunders, accountant, 47 Thurtleff Avenue, Chicago; Kate Watson, who graduated from the Illinois Training School for Nurses in 1893; Mary Ann Watson, who also graduated from the Illinois Training School for Nurses in 1893 and who married Joseph R Revington of Tralee on 1 June 1899 – from their son Joseph Revington (1903-1954) descends journalist and writer Gordon Revington; Jessie Marion Watson, born 13 November 1870, married James Nesbitt of Grasmill on 22 Nov 1900; Christina Jane Watson, who married James Legate of Southsea on 14 February 1902 in Tralee. Gordon Revington, by email dated 24 July 2022, advises that ‘David George was the third son, John being the eldest, and Gerald Pierce Watson, Thomas Watson, and Sydney Buxton Watson were others. Then there were Lucy, Margaret, Jessie Marian, Kate and Mary.’ Sydney Buxton Watson was born at Ballysheen on 26 August 1881. He was a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Reserve and described as youngest son of the late David and Mrs Watson of Tralee, Ireland, when he was married by special license to Beatrice Ethel, daughter of late George Henry Layton, Southsea, on 22nd Mary 1917. The ceremony took place at St Peter’s Church, Hants. Beatrice Ethel Watson, wife of Sydney Buxton Watson, Commander RNR, died at St Helens, Down End Road, Drayton, Portsmouth, Hants on 25th March 1956. Sydney Buxton Watson’s service record is held in the National Archives https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D8294042 In 1907, Gerald Pierce Watson of Fortlands, Tralee was sworn in as a Justice of the Peace for County Kerry. He seems to have resigned in 1920. [14] Kerry Sentinel, 12 January 1901. ‘The deceased gentleman farmed extensively and most successfully at Ballysheen, near O’Dorney, and at Ballymoreigh, near Dingle, but some years ago gave up farming altogether. He nevertheless took a keen interest in all matters appertaining to agriculture and was one of the most active members of the Kerry Agricultural Society’ (Obituary, Kerry Weekly Reporter, 12 January 1901). In the Census of Ireland 1901, his widow, Jane, was aged 55. [15] ‘The Tralee Farmers’ Co-operative Society has purchased Messrs Watsons’ Creamery for a sum not very far short of £5,000’ (The Liberator Tralee, 22 April 1920). ‘Not a lot is known of Lee Strand in its pre co-operative days. We know that it functioned as a creamery under the name of Watsons before being bought by a local farmers’ co-op in 1920. In 1933, Patrick O’Sullivan took over as manager of the creamery and it was he who laid much of the foundation for the future success of Lee Strand … it was in the 1950s that the real expansion of Lee Strand took place (‘How Lee Strand has survived’ (Kerryman, 25 November 1983). The following suggests that Watson’s Creamery, Tralee was located near the Protestant Church: ‘Charles Hanlon (butcher) has been using a house in Church-lane, the entrance to the Protestant Church and Watson’s Creamery Company’ (Kerry Sentinel, 30 July 1898). Gordon Revington, by email dated 24 July 2022, advises: ‘The creamery was on the site of a former mill in Church Street but I have been unable to remember the exact location. What I imagine was the office of D & G Watson Creamery Ltd was 8 Nelson (Ashe) Street. David Watson served on the Tralee Board of Guardians and on the Board of the Dingle Railway. Another curiosity is that the home that Jane occupied at Ballymullen, Tralee (near the Munster Bar) after her husband died had a swimming pool. In 1912, Gerald Watson (David’s brother) said that the Watsons owned six creameries and four auxiliaries. There were nine creameries in the group when they were taken over in the Kerry Co-operative Dairy Societies deal in 1928 but what became Lee Strand had already been sold before that.’ Gordon Revington adds the following by email dated 5 August 2022: ‘The Church Street creamery was, I think, in the building that extended from Church Street into Church Lane (which runs directly behind it). Lee Strand had a shop and office on the western side of Church Lane up to the time that the whole operation moved up to Ballymullen. It may even be that Watson's occupied a property that had actually been Revington's, because there is a note in an article in The Kerryman written by Con Casey at the Centenary of Revington's in 1957 that the initial woollen factory was operating at Church Lane in 1881 … it has also been stated that the first instance of a Revington engagement in the commercial life in Tralee was at Church Lane. The roof of the drying room at Revington's factory was blown off in a storm in November 1881. An advertisement in the Kerry Sentinel in that year indicates that it was in Church Lane. That being said, the person who had probably provided this information was a grandson of the first of the family to come to Tralee (my father) and he was no longer a viable provider of evidence …Marmion’s History of Maritime Ports of Ireland (1871) lists Flaherty and Watson as a butter merchant in Church Street, so the thread is a bit complicated. This was far earlier than I understood David Watson to become involved in buttermaking. The Kerry Weekly Reporter in January 1895 states that he had acquired a mill from Mr. Leahy in Church for the purpose of establishing an open creamery there … If I remember correctly, the horse and carts used to line up northwards along Ashe Street (or Nelson Street, as it was up to the mid-1950s, in official terms) and the intake point was in Church Lane, but I may be mistaken.’ Gordon Revington, by email dated 24 July 2022, adds the following to Kerry creamery history: ‘There is another tenuous connection between my family and the creamery business, the case of McEllistrim vs Ballymacelligott Agricultural and Dairy Co-operative Society Ltd which went to the House of Lords and caused a lot of aggravation in Ballymac at the time. The issue was covered under restraint of trade, with the farmer claiming that he had the right to deliver his milk to any creamery he wished rather than exclusively to the co-operative. The Slattery family, big merchants in Tralee and later to build the bacon factory that later became Dennys, bought a creamery at Kilquane, just a few kilometres from Ballydwyer. The ill-feeling that erupted about milk supplies really got serious in September 1919 when the Slattery premises was seriously damaged by four explosive charges and the company entered a claim against the County Council for malicious damage. The parish priest, Fr. Trant got involved and made a number of observations which further inflamed the situation. A horse was shot and there was an incident of a house being fired upon. The barrister Serjeant Alexander Sullivan (who had been on Sir Roger Casement's defence team) was engaged by Slatterys to pursue the claim for damages. He was staying with one of the Slattery family, Edmond, the solicitor, at Derrybeg House in Oakpark. On January 9, 1920, seven or possibly eight men entered the house, confronted the lawyers and EB Slattery's wife and one of them aimed a revolver at the barrister. I imagine that there was no intention to use the firearm but simply having guns around does seem to mean that they get to be used. Sullivan made a grab for the revolver and it discharged. The bullet grazed his left eye and singed his eyebrow. It went that close to being a matter of very serious import. The man who had had the gun lost his mask in the struggle. Five men were charged with being involved in the incident but the judge threw the cases out because of the failure to identify the culprits in Cork in March 1920. However, to go back to the men entering the house, and maybe an indication of the rather haphazard and poorly organised approach to the whole escapade, they firstly went to the house next door, which happened to be where my grandfather and grandmother (Mary Ann Watson, daughter of David) were living at the time. A servant informed the men that they were in the wrong house so they took off to go to the correct one.’ [16] ‘Died in Edinburgh during a visit to his daughter, Mrs Pringle. A letter was received by his son Philip Watson yesterday that his father had a sharp attack of influenze … it is believed the remains will be brought to Tralee for interment at Ballyseedy’ (Kerryman, 26 June 1926). [17] ‘Mrs Eleanor Frances Latchford, who died in the Bon Secours Hospital, Tralee on Sunday January 11, was wife of the late Mr Frank Latchford, former Managing director of Latchford’s Ltd, Tralee … Mrs Latchford (née Watson) was born in Ventry but later moved to Abbeydorney. Her father, Mr Gerald Watson, started the first creameries in Kerry’ (Kerryman, 16 January 1981). [18] ‘In this county two groups of proprietary creameries (those of Messrs Watson, Tralee and Dennehy, Currow) have recently been purchased, the total number of creameries concerned being twelve, of which nine belonged to Mr Watson and three to Mr Dennehy.’ [19] The following announcement appeared in 1898: ‘A marriage has been arranged and will shortly take place between Mr August Wilhelm Lofmark of Gothenburg, Sweden, and Miss Pauline Thompson, second daughter of the late Mr Thomas Thompson of Arnold Villa, Monkstown, County Dublin’ (Kerry Evening Post, 19 November 1898). The Census of Ireland 1901 records Wilhelm and Pauline Lofmark resident at Nangor, Clondalkin, Dublin. [20] Kerry Weekly Reporter, 24 June 1893. It is worth noting that in March 1896, tenders were invited to build a Co-Operative Agricultural Creamery in Castleisland. [21] In 1894, John Kerins O’Connor and Wilhelm Loffmark, proprietors, were prosecuted under the Contagious Diseases Animals’ Acts of 1878 and 1886 for taking milk from houses where infectious disease, typhoid fever, existed. The company was fined £5 (Kerry Sentinel, 31 March 1894). [22] Kerry Sentinel, 3 June 1899. [23] Copy held in Castleisland District Heritage IE CDH 31. [24] Thesis held at Trinity College (Dublin, Ireland), Department of History, 2010. Includes photograph of Castleisland Cattle Breeding Station.