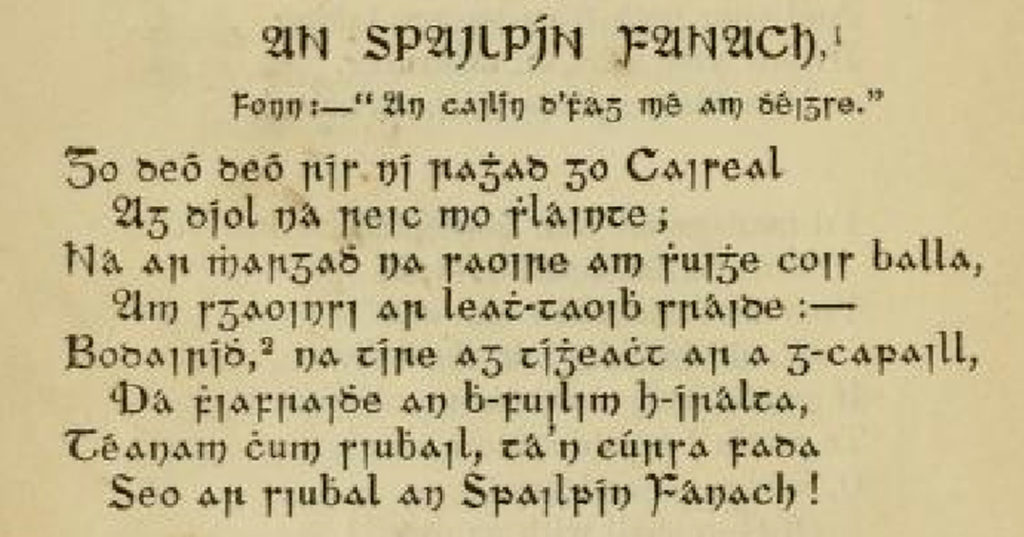

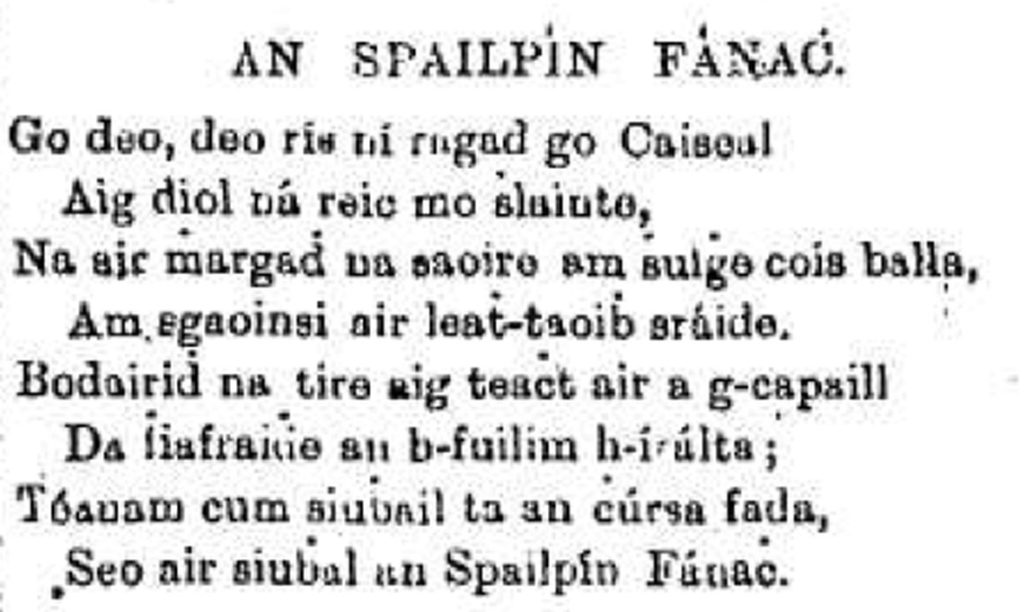

Two versions of the song, An Spailpín Fánach (The Roving Spalpeen) are held in the collection, one from Munster and the other from Connemara. The song dates to circa 1797:

The Irish Spáilpin fánach , the ‘Roving Spalpeen’, designates one of the flock of migratory labourers once so common when tillage was more used in Ireland. The bard was one of those who had been dispossessed in the Penal times; he joined the roving Bohemian band but soon put away the sickle for the sword.1

In an essay on bulls, an eighteenth century writer compared an ‘industrious English artificer’ to an Irish Spalpeen who ‘careless and content sits beneath the shade of a spreading furze bush to watch a herd of oxen’ and suggested it was an idyllic life for a philosopher.2

In 1860, Irish scholar and bookseller, John O’Daly (1800-1878) provided background to the song:

This song … is the production of an itinerant potato digger from Kerry who suffered some hardship among the farmers of Tipperary and Kilkenny, a class of men who though willing to pay the highest amount of wages to their men, yet require adequate labour in return. However, the Kerry spalpeens, as they are called, are an object of hatred to their fellows of Tipperary where shoals of them muster from the Kerry mountains to earn a few shillings during the potato-digging season, and hire themselves far below the natives, for which they are severely punished.3

Roots in Castleisland

O’Daly revealed the song had its roots in Castleisland and that the ancestors of its author hailed from the borders of the river Galey:

The Spailpín Fanach No more – no more in Cashel town I'll sell my health a-raking; Nor on days of fairs rove up and down, Nor join the merry-making. There, mounted farmers came in throng, To try and hire me over; But now I'm hired, and my journey's long, The journey of the Rover! I've found, what rovers often do, I trod my health down fairly, And that wand'ring out on morning's dew Will gather fevers early. No more shall flail swing o'er my head, Nor my hand a spade-shaft cover, But the Banner of France float o'er my bed, And the pike stand by the Rover! When to Callan, once, with hook in hand,4 I'd go to early shearing; Or to Dublin town – the news was grand That the 'Rover gay' was nearing. And soon with good gold home I'd go, And my mother's field dig over – But no more – no more this land shall know My name as the 'Merry Rover!' Five hundred farewells to Fatherland! To my loved and lovely Island!5 And to Culach's boys – they'd better stand Her guards by glenn and highland. But now that I am poor and lone, A wand'rer – not in clover – My heart it sinks with bitter moan To have ever lived a Rover. In pleasant Kerry lives a girl, A girl whom I love dearly, Her cheek's a rose, her brow's a pearl, And her blue eyes shine so clearly! Her long fair locks fall curling down O'er a breast untouched by lover; More dear than dames with a hundred pounds Is she unto the Rover! Ah, well I mind when my own men drove My cattle in no small way – With cows, with sheep, with calves they'd move, With steeds too West to Galey;6 Heaven willed I'd lose each horse and cow, And my health but half recover, But it breaks my heart for her sake now That I'm only a sorry Rover. When once the French come o'er the main, With stout camps in each valley, With Buck O'Grady back again, And poor brave Tadg O Dalaigh. The Royal Barracks in dust shall lie, The yeomen we'll chase over, And the English clann be forced to fly, 'Tis the sole hope of the Rover.7

Indeed, Castleisland was identified in the following verse:

My five hundred good wishes to the home of my father and to kindly Castle Island,

And to the boys of Cool; they used not to be slack at the time for turning up the gardens.

But now as I am a poor stricken outcast in these strange lands,

‘Twas a sorry day I ever got the title of Spailpin Fanach.8

______________________

1 Description (and translation) by Dr George Sigerson (1836-1925) in Bards of the Gael and Gall (1907), pp187-189. Mrs J Sadlier alluded to the song in her book, The Hermit of the Rock. A Tale of Cashel (1885).

2 Essay on Bulls by Taurus Mac Toro, Smithfield, 29 September 1785. He added: 'His unclothed legs drawn up towards his mouth and whilst his knees support his elbows, his fingers skillful touch a pair of jews harps that vibrate to his breath the song of Coolun'.

3 The Poets and Poetry of Munster (1860) by George Sigerson (under his pseudonym, 'Erionnach') and John O'Daly. He added: 'In the beginning of the present century many of the Kerry men had their ears, or one of them at least, cut off as a punishment for lowering the market wages. The mode of detecting a Kerry man from other Munster men was as follows. All the spalpeens, who slept huddled together in a barn or outhouse, were called up at night, and each man in his turn was obliged to pronounce the word goat in Irish; when the long, sharp tone of the Kerry man betrayed him, and immediately his ear was cut off. It is said that Eoghan Rua, the poet, had a narrow escape of losing both ears on one occasion'.

4 O'Daly identified Callan in the county of Kilkenny.

5 In his translation, O'Daly states 'Castle Island is referred to here'.

6 O'Daly identified the river Galey or Gale in Kerry, 'for a description of which see Smith's Kerry, pp 213, 338. On its borders the poet's ancestors were located'.

7 The Poets and Poetry of Munster (1860) pp 76-80. The song was also published under title, An Spailpín Fánac to the air, 'The Girl I Left Behind' in the Kerry Weekly Reporter, 13 April 1895 ('An Teanga Gaedhilge. Beid an Gaedilge Faoi Meas Fos'. Translator not stated but perhaps 'Canon Burke', who contributed elsewhere to the page). Canon Ulick Joseph Bourke (1829-1887) was author of Easy Lessons: or, Self-Instruction in Irish.

8 Freeman's Journal, 5 July 1894. Review of 'Easy lessons in Irish' in the Gaelic Journal.