The following extract was included in a short sketch of County Kerry written in 1898 and published in serialised form in a local newspaper.[1] The sketch was the work of Miss Anne Margaret Rowan, daughter of Archdeacon (and author) Arthur Blennerhassett Rowan of Tralee. Miss Rowan, who was born in Tralee in 1832, was also the author of Norah Moriarty; or, Revelations of Modern Irish Life (1886) and Life in the Cut (1888). Her Memories of Old Tralee, written in 1895, was reproduced, with short introduction, in 2016.[2]

Some spellings, passages and dates may be queried, and it is impossible to know if transcription errors occurred during publication in 1898. Miss Rowan complained of this problem herself to the editor of the newspaper:

You do not give me an opportunity of correcting for the press; consequently errors in words, and punctuation which alter meanings, and which it is hopeless to try to correct in a letter, occur in each article. Correspondents who are interested in these articles write to me, pointing out some evident mistakes, and asking questions as to points made obscure by typographical errors.[3]

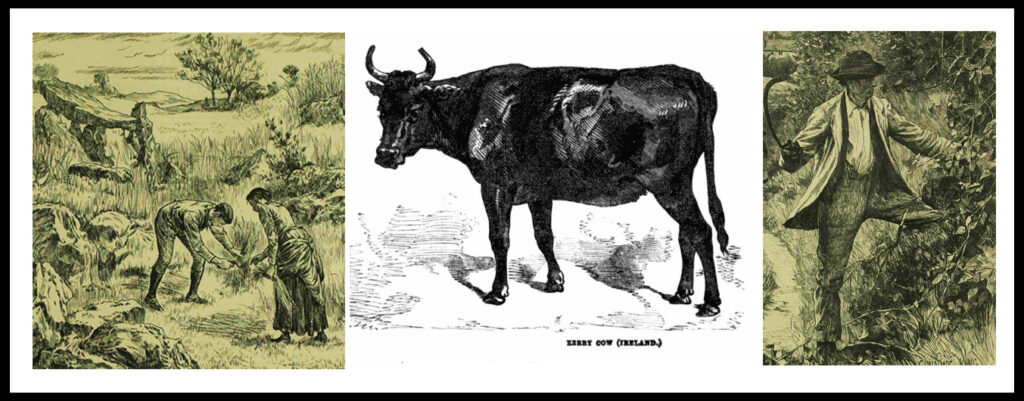

The extract relates to an 1814 report of the Farming Society of Ireland. This organisation was founded in 1800 by the Marquis of Sligo and the Rt Hon John Foster, under the patronage of the Dublin Society, its objective to improve the agriculture and livestock ‘of this kingdom’:

Gold medals and premiums of twenty, ten, and five pounds, according to the different classes, shall be given to those who produce the finest bulls, cows, and heiffers, of any kind, at a shew of black cattle and sheep to be holden at Ballinasloe on Wednesday the 8th day of October next and also at a like show on the first Thursday in November next at Smithfield market, Dublin.[4]

It evidently ceased to exist in about 1828 when its activities were taken over by the Dublin Society.[5]

Miss Rowan’s sketch in full follows the extract.

Extract from Report of the Farming Society of Ireland, 1814 Truaghnacmy – Mr Meredith of Dicksgrove works his land well and has fine crops. He uses a Hereford plough drawn by well-trained bullocks and is most anxious to encourage his neighbours to improve their methods. Mr Harnett has some fine ground, so has Mr Powell at Castleisland. This Mr Powell, who is Mr Herbert’s land steward, holds under Mr Herbert of Muckross. It is the model farm of the neighbourhood. In 1806, he took 140 acres at £200 per annum. He has inclosed it, partly with a wall five feet high, divided it into fields, built a nice house, started an orchard, well cropped and stocked his land, his South Down ram lambs fetching five guineas each. The town of Castleisland is unimproved, and there are six hundred acres close to the town in a state of nature. This is part of Lord Powis’s estate which remains undivided, therefore unworked, as one of the six proprietors is generally a minor, so that no leases can be legally made; the tenants, therefore, have no security. William John Crosbie is now the minor. Lord Powis’s head rent is £1,800 per annum. The present lettings bring in £18,000 per annum ground letting here at £5 or £6 per acre per annum as dairy land and dairys are the principle method here. Mr Hussey has a dairy here of 36 cows. This is managed by one man, one woman and two girls. The butter, which is excellent, is made in a shabby mud house, without windows, because glass is supposed to be bad for butter. This butter is packed in firkins and sent in loads of 14 to Cork which is forty miles away.

A Short Sketch of Co Kerry by Miss A M Rowan

Ardfert and Aghadoe[6]

From very early times the Sees of Ardfert and Aghadoe were united, each possessing their own cathedral.[7]

The vicissitudes of these cathedrals were various, both of them being destroyed and rebuilt several times. The Annals of Innisfallen mention that Aodh (McConnor McAuliffe Mor) O’Donoghue, King of Loch Lein, was buried AD 1231 in his ancient Abbey of Aghadoe.[8]

The supposed date of this cathedral was the sixth century; the rude form of the structure betokens this antiquity, as there is no sign in the ruins of that more educated ornamentation usually to be found in more modern edifices; also, the fact that the monks of Innisfallen, which was then an old Abbey in 1213, describe Aghadoe as ancient in the 13th century, betokens that Aghadoe was as old, if not older, than Innisfallen.

Ardfert Cathedral was destroyed many times by internecine wars. The Annals of Innisfallen describe its being ‘plundered by the McCarthys AD 1160, who brought much prey with them and killed many people even in the churchyard.’ The last and most important rebuilding of Ardfert Cathedral was undertaken by the Fitzmaurices in or about the 14th century, its final ruin being in 1641, when ‘the Irish army destroyed and wasted the cathedral and all the adjoining district.’

There was no attempt made to repair Ardfert after 1641, but until late in the last century [18th], a few monks clung to their ruined church. During the early part of this century [19th] one of the aisles of Ardfert Cathedral was roofed in and used as the parish church until the present pretty one was erected.

Those who were consecrated to this old See as Bishops of Ardfert and Aghadoe were as follows:

494 Saint Brendan – 494 to 577, born at Fenit, and a disciple of Jarleth of Tuam, is said to have created this diocese and named it (well as Clonfert) after his spiritual father Ert, Bishop of Slane. It is well to remark that there were three different Brendans, Bishops of Ardfert and Aghadoe. 1075 Dermot Mac Miol Brennan, written Mal Brendan 1152 Magrath O’Ronain, attended Synod of Kells, 1152, as Bishop of Ardfert Next appears Ziolla Mac Aiblan O Hanmada 1193 Donald O Connap, called Bishop of Munster, 1193 Next appears David (?) O Deribthitpib 1215 John, the first of whom we have the assured date is John, an English Benedictine monk, consecrated 1215. He was deprived of his See in 1221 and retired to the Abbey of St Albans, where he died 25 years after 1225 Gilbert, consecrated 1225, resigned 1237 1237 Brendan 1252 Christian 1264 John 1285 Nicholas 1288 Nicholas. He was called bishop of Kerry and died at a great age, AD 1336 1336 Man O Hathern. Pope Benedict XII, in 1341, appointed Edmund de Carmarthen to this See but as the See was thus occupied this nomination had no effect 1348 John de Valle, nominated by Pope Clement VII, 1348 1372 Cornelius O Tizernach, nominated by Gregory VII 1379 William Bule 1410 Nicholas Fitzmaurice, son of 7th Lord Kerry, 1410-1431 1462 Maurice, provided by the Pope, died 1462 1480 John Stack, provided by Pius II, neglected his duty and was superseded but again appointed by Sextus IV. He attended the Synod of Fethard 1480 and was buried at Ardfert 1488 1488 Philip, a secular priest, who had previously superseded John Stack, was again appointed to Ardfert by Innocent VII in 1488 1495 John de Geraldyn, provided by Alexander VI, 1495 1555 James Fitzmaurice, Bishop 1555-1583. There were two Fitzmaurices bishops 1588 Nicholas Kenan, died at Limerick 1599[9] 1600 John Crosby, a graduate in the schools of the English race, and yet is skilled in the Irish tongue. This bishop was of the race Mac y Crossane, who was hereditary Chief Rhymer of the O’Moores of Lex. He died 1621, and was buried at Ardfert 1622 John Steere, Bishop of Fenabore, or Kilfenora, consecrated Bishop of Ardfert 1622 1628 William Steere, brother of late bishop 1641 Thomas Fullar, alias Fulwar. Note there were two Fullers bishops 1660 Edward Synge, consecrated Bishop of Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe being held in commendam therewith. Since 1660 the Sees have been so united – Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe Next appears William Fuller DD, of Cambridge and Oxon, 1663, afterwards Archbishop of Cashel. Woods Fasti Oxon AD 1660, August 2, Doctor of Law. William Fuller, sometime of St Edmund’s Hall. He was afterwards Bishop of Limerick, and at length of Lincoln 1667 Francis Marsh, of Kilmore and Ardagh, 1672 1672 John Vesey, Archbishop Tuam 1678 1678 Simon Digby, Elphin 1691 1690 Nathaniel Wilson from Worcestershire recommended to Ireland, where he became chaplain to Duke of Ormond – a great preacher 1695 Thomas Smith, Dublin University 1725 William Burscough 1725 James Leslie, son of Dean Leslie, who obtained Seignory of Tarbert for his services to William III, and who died with the King’s letter in his pocket, with his promotion to a Bishopric 1755 John Averal 1772 William Gore, translated to Elphin 1772 1772 William Cecil Perry 1784 or 1794 Thomas Barnard, died 1806. Of him Goldsmith wrote, ‘Here lies the good Dean reduced to earth,/Who mixed reason with pleasure, and wisdom with mirth;/If he had any faults, he has left us in doubt –/At least in six weeks I could not find them out.’ 1806 Charles Mongan Warburton, translated to Cloyne 1820 1820 Thomas Elrington, Provost Trinity College Dublin, translated Ferns 1822 1822 John Jebb, died 1833 1834 Edmond Knox 1849 William Higgin, translated to Derry 1853 Henry Griffin 1866 Charles Graves[10]

The dignitaries of the Diocese of Ardfert and Aghadoe were apportioned as follows:

To the Deanery was attached the Rectory of Ratass, the Rectorial tythes of Killanecar, with [?] acres of Glebe in Rathass, and 37 acres of glebe in Ardfert parish. The Dean at one time had also one fifth of the tythes of Ardfert parish but these afterwards fell to the Ecclesiastical Commission for Ireland. The Precentor had the vicarial tythes of Kilfeighney and Ballyconry parishes, and one-fifth of the tythe of Ardfert parish; Glebe in Kilfeighney, and 71 acres of glebe in Ardfert parish. The Chancellor had the tythes of Kilmalchedar and the Rectorial tythes of Fenit, with one-fifth of the tythes of Ardfert parish, which reverted to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The Treasurer. To this was attached the rectory of Kilconly, the vicarage of Kilclinty, with glebes in each parish, and one-fifth the tythe of Ardfert parish. The Archdeaconry. To this belonged the Rectory of Ballinvoher, one fifth of the tythe of Ardfert, and 15 acres of glebe in said parish.[11]

An old manuscript in Rolls House, London, styled ‘Steer’s Memorial’ dated 1692 is written by Major Steer, probably a near relative of the Bishop Steer, who was called ‘the grand informer of Kerry’ and who supplied government with much information as to ecclesiastical matters in the diocese. He advises that the diocese of Ardfert and Aghadoe be separated. Smith’s History of Kerry written in 1754 gives a detailed account of the then wretched condition of the diocese of Ardfert and Aghadoe where there were only sixteen churches in any kind of repair, all others being in ruins, the Cathedral Church of Aghadoe in ruins, ‘time out of mind.’

In Camden’s day, ‘Ardarte’ was a wretchedly poor diocese. It is thus described, ‘The bishops called of Ardfert a poor one, God wot hath his poore See.’[12]

Generation after generation this diocese was further reduced, lands being alienated, until 1660, when seemingly shorn of worldly goods, the bishopric was annexed to that of Limerick, to which it as present belongs. Smith says the diocese was at one time styled the Bishopric of Kerry but the only bishop we find actually consecrated Bishop of Kerry was Nicholas (the Cistercian) Abbot of O’Dorney who was elected Bishop of Kerry AD 1288. A remarkable suit was brought against this bishop and four of his clergy.[13]

They are said to have forcibly taken the corpse of one Cantil (probably present Cantillon) and beaten some of the Friars of the Franciscan Abbey at Ardfert.[14]

This See, in an old taxation book, is charged £12 13s 4d sterling for First Fruits; the Deanery and Archdeaconry £3 each; the Chantor, Chancellor, and Treasurer, £2 each, and the Archdeacon of Aghadoe, £1 10s sterling. In the registration book there is no distinction made between the parishes in Ardfert and Aghadoe, the former being described as North Kerry, the latter as Desmond district of the diocese.

Major Steer recommended that the county at large should be charged with the repairs of the cathedral churches of Ardfert and Aghadoe and that account should be rendered of the £200 already paid for that purpose. He says an able Dean is much needed for Ardfert and Aghadoe, there being a dispute between Dr Bladen and Dean Richardson, ‘who are of no use here. Dr Bladen resides in Dublin, where he is well beneficed, and Dean Richardson in London, where he has £300 per annum. The Dean of Limerick is also Archdeacon of Aghadoe, for which he has £120 per annum though he resides on his Limerick Deanery, where he has £300 per annum.’

Ecclesiastical history of this country demonstrates that from early in the 15th to close of the 18th century the churches in Ireland were in a sorry condition. In 1576, Sir Henry Sidney said there were ‘few resident parsons or vicars, in most places a very sorry curate … on the face of the earth, where Christ is professed, there is not a church in so miserable case.’

A little later Spenser, later again, Stafford, tell the same story, mentioning amongst other causes that ‘the possessions of the church being to a great proportion in lay hands’ causes much evil.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, there were but 16 churches in use in Kerry; ninety years later there were 38, of which I give a list. The late Archdeacon Rowan collected exhaustive details of the diocese in 1841 when he contemplated writing a history of Kerry; from these I extract the followings items. The population is from the census of that year.[15]

Aghadoe – Patron, the bishop, census 4,897; rent charge £279 13s 9d; glebe land valued at £49. In 1754 this parish had only a ruined church and each of the dignitaries paid 10s proxy fees. Aghavallin – Patron Staughtons; was in good repair in 1754; in 1841 joined to Listowel. Aglish – Patron Earl of Cork; census 1,939; rent charge £18 10s 2d; glebe land £29 10s. Ardfert – The bishop, patron; census 5,334; rent charge £142 8s 5d; glebe land £18 9s 2d. Ballinacourty, with Minard and Stradbally – Patron [?], census 1,412 – 1,666 – 1,202; rent charge £63 11s 3d – £57 6s 11d – £40. Ballinahaglish (part of Ardfert) – Patron Sir E Denny; census 2,147; rent charge £121 3s 1d; glebe land £55 7s 8d. This church is now closed (1898). To it was united St Anna and Clogherbrien, part of Tralee. In 1754 both these churches were in ruins. 10s each were then paid in proxies. Ballinvoher – Patron, the bishop; census 3,579; rent charge £152 6s 5d; glebe £4 12s 3d. Ballycushlane (part of Castleisland) – census 5,701; rent charge £345 9s 5d. In 1754 this church was in ruins, and the patron was the Earl of Powis, alias Lord Herbert; proxy 10s. Ballymacelligott – Patron, Crosbie of Ardfert (?), alternate with others; census 4,056; rent charge £252 13s 10d. In 1754 this parish was in gift of Sir M Crosbie, one of the alternate patrons. There were then six acres of glebe and two-thirds of the great tithes of that part of the parish of Currens north of the Mang attached to the rectory. The church was in good repair and the proxy was 10s (Nohoval and part of Currens attached). Ballyseedy (part of Ballymacelligott) – Patron, Blennerhassett; census 1,472; rent charge £45. There was no church until the present pretty one was built in 1878. Ballyduff – Patron, Earl of Cork; census 488. Ballyheigue – Patron, the bishop; census 4,725; rent charge £218 1s 6d; glebe £40. In 1754 this church was in ruins; proxy 10s. Brosna – Patron, the bishop; census 2,871; rent charge £131 5s; glebe £5 5s. In 1754 church in ruins; proxy 10s. Caherciveen – Patron, the Crown; census 6,315; rent charge £170 5s 10d; glebe £98 14s. Attached are Glanbegh and Killinane. Castleisland – Four (six?) alternate patrons; census 7.967; rent charge £479 3s 11d; glebe £52. In 1754 this church was in good repair, and the patron was Earl Powis. Clahane (part of Castlegregory) – patron, the bishop; census 2,994; rent charge £138 9s 2d. Currens – Joined to BallymacElligott and Kiltallagh – census 2,067. With Currens in 1754 was Cullen, the King was then patron, and both rectories and churches were in ruins. Dingle – Patron, Lord Ventry; census 6,206; rent charge none. Drishane (part of Knocknacappul) – Patron, the bishop; rent charge £236 5s; glebe £50; joined to it is Nohoval-daly; rent charge £107 10s. Dromod – Prior – Patron, the Crown; census 5,247 and 3,323; rent charge £169 10s – £90. Drumtariff – Killineen – Cullen – Patron, the bishop; census not given; rent charge £150; with glebe £30 – £92 10s and £112 10s. Duagh – Kilcarra – Patron, Rev Robert Hickson; census 5,065 and 1,250; rent charge £1015s and £72 10s; glebe £47 10s and £42. Dunurlin – Patron, the bishop; census 2,125; rent charge £112 10s. Garfinny (part of Dingle) – Patron, the bishop; census 914; rent charge £34 12s 4d. Kenmare – Patron, the Crown; census 5,839; rent charge £159 8s 5d. Tuosist was joined to this; census 7,485; rent charge £170 0s 2d; glebes to both value £6 and £4 4s. Kilcolman – Patron, Crosbie, Ardfert; census 3,902; rent charge £34 12s 4d, glebe £20. Kilcrohane and Templenoe – Patron, Crown; census 10,776 and 4,189; rent charge £193 18s 2d and £91 14s 7d; glebes £30 and £40; were united to Kilcoleman. Kilmoily – Patron, the Crown; census 4,459; rent charge £150. Kildrum (part of Dingle) – Patron, the bishop; census 1,217; rent charge £27 18s 10d; glebe £3. Kilfeighney and Ballyconry – Patron, the bishop; census 2,388 and 417; rent charge £83 11s 6d and £13 10s; glebe £12 10s. Kilflynn with Kiltomey, Killaghin, Kilshanin – Patron, Earl of Cork; census 1,081 – 2,043 – 1,876 – 2,271; rent charge £31 18s 3d – £45 – £31 10s – £56 3s 2d, and glebe £4 10s. Kilgarvan – Patron, the bishop; census 3,988; rent charge £83 1s 6d; glebe £34 10s; united to Killaha; census 2,660; rent charge £90. Kilgobbin (with part of Killanene) – Patron, the bishop; census 2,384 and 1,745; rent charge £316 10s; glebe £40 and rent charge £69 4s 7d. Killarney (part of Kilcummin) – Patron, the Crown (by disqualification of the Earl of Kenmare); census 10,476 and 7,360; rent charge £180 and glebe £120; rent charge £166 3s 1d and glebe £68 5s respectively. Kiclinty, and part Kilconly – Patron, the bishop; census 2,728 and 2,210; rent charge £76 3s 1d and £62 6s 2d; with glebe, £60 and £6 6s respectively. Killiney – Patron, the bishop; census 3,481; rent charge £324 (sic) 13s 10d; glebe £13 16s 11d. Killeentierna and Dysert – Patron, the bishop; census 3,106 and 1,529; rent charge £212 10s 5d and £130 4s 6d; with glebe £42 18s 4d. Killorglin – Patron, the Crown; census 8,574; rent charge £300; glebe £22. Killury – Patron, Crosbie of Ardfert; census 6,480; rent charge £294 4s 8d; glebe £15. Kilmalchedar and Fenit – Patron, the bishop; census 2,333 and 315 respectively; rent charge £52 10s with £5 glebe, and £75. Kilquane – Census 1,760; rent charge £77 12 6d, with £8 glebe. Kiltallagh, Kilgarrylander and part Currens – Patron, the Crown; census 1,303 – 2,889 for the two first, with rent charge £124 12s 4d – £162 13s 10d, and glebes £15 and £20; the population of Currens not given; rent charge £78 with £10 10s glebe. Kinnard (part of Dingle) – Patron, the bishop; census 1,286; rent charge £62 6s 2d; glebe £6 15s. Knockane – Census 5,191; rent charge £196; glebe £45 2s. Listowel, to which are united Aghavallin, Lisselton, Galey, Kilohiny, Murlin, Kilnaughtin, Dysert, Finuge, Knockenure – all in gift of Staughton of Ballyhorgan; census Listowel 5,934; respectively: 6,606, 2,221, 3,041, 3,050, 3,293, 5,102, 1,296, 1,545, 1,358. Marhyn and Dunquin – Patron, Lord Ventry; census 973 and 1,394; rent charge £28 2s 6d and £28 2s 6d. Molahiffe – Patron, Crosbie of Ardfert; census 3,635; rent charge £120; joined to this Kilcredan and Kilbonane, in same gift, with census 754 and 3,666 respectively, glebes being £27 13s 10d and £138 9s. O’Brennan – Census 992; rent charge £51 18s 5d. O’Dorney – Census 3,142; rent charge none; glebe none. Rathass – Killanear (appertains to Deanery of Ardfert) – Patron, the Crown; census 2,836 and 1,746; rent charge £252 13s 10d and £69 4s 7d. Rattoo – Census 3,654; rent charge, none; glebe none. Tralee – Patron, Sir Edward Denny; census 12,534; rent charge £304 5s 9d with £46 glebe. Valentia – Patron, the Crown; census 2,920; rent charge £112 10s with glebe £50. Ventry – Patron, Crosbie of Ardfert; census 2,426; rent charge £90 with £1 10s glebe.

Total rent charge of diocese £10,920 10s; glebes £1,347 4s 8d. There are four parishes where census is not given. The census of the dioceses, as given in the list, is 276,522, about 50,000 more than the census of 1891. The population of five or six small parishes is omitted to be given which, for 1841, makes it almost a wide margin – about ten more thousand persons, so that the shrinkage of population in the last fifty years has not been so great as is generally supposed.

The following list of the population of Kerry for the last two hundred years is interesting. In the year 1692 population was 10,635; in 1754, 56,628; in 1841, 293,880; in 1851, 238,241; in 1891, 225,565.[16]

The County Kerry[17]

‘The coming of the English into Ireland’ AD 1172 is commonly but somewhat inaccurately called the conquest of Ireland by the English. For one or more centuries the inhabitants of these two neighbouring islands, sparse though they were in number, constantly raided one on the other. When an English, Welsh, Scotch or Irish prince suffered loss he immediately claimed aid from some neighbouring warrior to repair his injuries, offering as a reward for such help an opportunity to this assistant prince of ‘preying’ upon other adjacent districts. Prisoners were often taken. Irish and other princesses thus carried off were oftentimes married to and settled with their conquerors.

In the year AD 913, Irish from the south raided into Wales and carried off much prey. In 925, the Saxons landed and ravaged in Ireland. Edgar, King of England, then claimed Ireland as his. Again, in 966, the Irish took revenge in Wales. The Earl of Chester being deposed sought aid in Ireland, and led the Irish successfully in a great raid which reinstated him with increased power in Chester.

During the eleventh century, raids and reprisals were periodical events, notable raids of Irish in England taking place at the following dates, when the country was devastated and laid waste from the sea-shore to Chester in the north and Hereford in the south: AD 1041, 1049, 1054, 1070, 1087 and 1148. Thus, when Dermod Mac Murrogh, being banished from his Kingdom of Leicester, sought aid in England, he was but following the habit of the age and giving his allies an opportunity of revenging their wrongs on those who had previously preyed on them.

Strongbow’s advent, AD 1172, was but another raid into Ireland. He, with ‘strong hand’ took, and with ‘strong hand’ kept, his conquest for the period of his lifetime. In 1172, Ardfert was known as Cair-rei, and Aghadoe as Desmond district. I have before me a quaint manuscript, written in 1830 by Dr Maurice O’Connor, giving his family pedigree from ancient writings. It is headed O’Connor-Kerry. The pedigree of all the branches of the old clan from Fergus Prince of Ulster, cousin to Connor-Kerry of that province (Ulster) in the first century of our Redemption.

It is stated in this manuscript that the name O, or descendant of Connor, was assigned on the first adoption of ‘sirnames’ in the reign of Brian, Monarch of Ireland. Cier, son of Fergus, by Maude, Queen of Connaught, gave his name, Cier-rei, to this district, where he ruled. There are 55 O’Connors named as Kings of Kerry, ending with Shane O’Caha – John of the Battles – whose chieftain’s power was broken, tempo Elizabeth. The family territories were not entirely sequestered until Charles II, who bestowed the O’Connor’s estate in Irraghticonnor on Trinity College Dublin.[18]

The exterminating of old dynasties is always sad reading but the wear and tear of time destroys old families as it does other mundane matters, leaving nothing but the memory of what has been as an inheritance to later ages.

The McCarthy More, who had once reigned supreme in Desmond, where from the 14th century the Earl of Desmond had completely superseded him, was at this period, as well as the Earl of Desmond, outlawed, and their estates confiscated. At ‘the coming of the English’ AD 1172, besides O’Connor-Kerry and McCarthy More, the other great Kerry families were the sept of O’Donoghue Ross and O’Donoghue of the Glen, The O’Sullivan More, who had migrated from county Tipperary, possibly driven out from that richer district to the wilds of Iveragh, and the Moriartys of the same sept who settled about Dingle.

When Strongbow restored MacMurrogh in Leinster, Henry FitzEmpress, alias Henry II, landed at Waterford to claim allegiance from his subjects (the settlers) in Ireland. The first Irish prince who came to meet him at Waterford was Dermod, the McCarthy More, King of Cork and Desmond. Dermod submitted to him, did homage to him as king over all Ireland, and yielded up the keys of Cork to Henry the II.

Five years later, Giraldus Cambrensis, chronicler of the events of that ‘coming of the English,’ writes thus of the arrangements made between McCarthy and the king, ‘Therefore Dermod of Desmond, ie the McCarthy More, being brought to terms, and other powerful men of those parts, FitzStephen and Milo divided seven Cantreds (in Kerry) between them.’

When Strongbow came to Ireland, he was accompanied by a large party of his kinsfolk. These were Henry Miles and Robert FitzHenry, his own brothers, Robert FitzStephen, and Maurice FitzGerald, his two step brothers, all sons of his mother Nesta, who was the daughter of an Irish princess. Besides these brothers there were Raymond FitzWilliam, known as Le Grosse, the son of another brother, also Miles and Richard de Cogan, sons of their sister, and a nephew of Strongbow, named Harvey de Mont Marisco, who was married to a daughter of Maurice FitzGerald’s.

The settlement of this large family party in Ireland was a strong measure, which planted ‘the English’ or, more correctly, the Norman conquerors of England, in Ireland, which step henceforward considerably altered the conditions of life in this country.

A third member of these newcomers came to Kerry on the invitation of Dermod McCarthy, to aid him in suppressing a family rebellion. Maurice, son of Raymond FitzWilliam, was with his father at Limerick when Dermod sought his assistance. He crossed Slieve Luchra, re-established Dermod’s authority, who, as reward, bestowed upon him a tract of country henceforward known as Clanmaurice.

Maurice FitzWilliam, married his cousin, Johannah FitzHenry, and with her received the estate of Rathoo, Kilury and Ballyheigh. Later on King John added to Fitzmaurice’s country 10 knights’ fees in Iveforma and Iferba, in Kerry, reaching from Beale-tra to Grahan (Beale to Scrahan?).

In time, the descendants of these settlers fell out with those who first gave them lands in Kerry. Nicholas FitzMaurice, 4th Lord Kerry, oppressed the McCarthy More. In the year 1325 Lord Kerry killed McCarthy More’s son and heir, Dermod, in the presence of the Judge of Assize, at Traly. For this murder, Lord Kerry was attained by parliament and forfeited all the estates granted to his ancestors by Richard the 1st.

The 5th Lord Kerry was ‘restored to title and part of the estate.’ In 1581, Thomas, 16th Lord Kerry, rebelled against his sovereign, and lost his estate, a portion of which was restored to his son. Other generations also rebelled, estates were confiscated, and in reduced quantities restored to the succeeding Lords of Kerry, those who quelled their rebellions being generally rewarded with a slice of the confiscated estate.

Early in the present century [19th], the last Lord Kerry, having no son, sold the estate remaining in Clanmaurice. I believe the old tomb at Lixnaw is the one piece of property in Clanmaurice remaining to the Fitzmaurice family. Some fifty-five years ago, my father, Archdeacon Rowan, called the late Lord Lansdowne’s attention to the dilapidation of this tomb, to which he replied:

You are perhaps aware that this ancient Kerry property has long passed out of my family, the late Lord Kerry having agreed to part with it to other proprietors at an early period of his life, which may account for no attention having been paid to its preservation. I shall write to Mr Trench, and request him to have it put into a decent state, though from the many demands upon me from the other property which I possess in Kerry, and which absorbs the whole of the receipts from it, I should do no more at present.

This tomb is now merely a shelter for cattle![19]

At Lord Kerry’s death, his title merged in that of a junior branch of the Fitzmaurice family. Lord Lansdowne descended from the Honourable John FitzMaurice, younger son of Lord Kerry, whose sister was married to Lord Shelburne. On Lord Shelburne’s death, he having no son, his estate – the Petty estate at Kenmare – was willed to his wife’s nephew, the Honble John Fitzmaurice. With these greater lords there came to Kerry, in the 13th century, gentlemen of the following names: Le Broun, or Brown, Ferriter, Cantillon, Moore, Rice, Trant, Walsh, Haore, Hussey.

The Fitzgeralds, Lords of Desmond, whose reign in Kerry was a striking episode, came over with Strongbow but settled at first in Offaly and Naas, Maurice Fitzgerald’s great grandson, Thomas ‘The Great’ being the first of that name to settle in Kerry. He came at the close of the 13th century. Thomas married Ellinor de Marisco and with her received ‘estates in Kiery.’

Their son, known as John of Callan, married Margery FitzAnthony, and with her had estates in Decies (Waterford) and Desmond. Another son of Thomas’s named Maurice, who was also killed at Callan, married Julianna Cogan, heiress of Lord Cogan, and with her had the territory given by Henry the II to Milo de Cogan. Thus the Fitzgeralds’ power and wealth increased rapidly in Desmond. In the original grants of the Desmond estates to the Fitzgeralds they are thus described, ‘reaching over the kingdom of Cork, towards Cape Brandon, on the sea coast (Kerry) and thither towards Limerick and other parts, as far as the water near Lismore (Waterford) which runs between Lismore and Cork and falls into the sea.’

With the Fitzgeralds the following gentlemen came to Kerry: the Stackpoles, Laundrys, Crispyns, Lodyns, Flemynges, Ambroses, Cradocs, Harveys and Rannels. In the rebellions of following centuries, many of these lost their hold on Kerry and moved elsewhere.

In the rebellion of 1588, the Desmond, who had been two hundred years a power in Kerry, forfeited all his estates which were distributed amongst those who helped to quell his rebellion.[20]

The New Settlers

After the confiscation of the Earl of Desmond, the McCarthy More and the O’Connor-Kerry properties, at close of the 16th century, a new group of settlers were planted in Kerry. Curious to know, this group of newcomers, like Strongbow’s party, were near relatives. Lords Grey and Walsingham, who were the Queen’s authorities in Ireland, were closely connected, and it was in Kerry that they helped their relatives, all of whom had aided in quelling the Desmond’s rebellion, to estates.

Those so placed were Sir Walter Raleigh, Ned Denny, two Chapmans and two Greys, all close cousins. Besides these there were Valentine Brown, also a connection from Crofts, in Lincolnshire, to whom, besides his grant of 6,560 acres, Donald MacCarthy, Earl of Glencar, alienated and sold a portion of his possessions which are remaining til today in this same family (Lord Kenmare). Last, but not least renowned, Edmund Spenser, the poet and statesman, who knew Ireland well and Irish character better than any man who has come to Ireland since.

Edmund Spenser was secretary to Lord Grey; he marched with him and his army of 800 men over Slieve Luchra into Kerry and has left an invaluable record of the Ireland of that day in his ‘Vue of Ireland.’

Within twenty years Sir Walter Raleigh’s spirit of adventure calling him elsewhere, he, Edmund Spenser, and one of the Chapmans, sold their Kerry lands to Sir Richard Boyle, Clerk of the Council of Munster, who was afterwards first, and the great, Lord Cork. Some of these Kerry estates were willed by the 1st Lord Cork to his second son, and are today in the hands of his descendant, the present Lord Cork.

Portion of these were, however, vested in the eldest son, the second Lord Cork, but this branch, being extinct in the male line, those estates, which were unentailed, passed by marriage in the female line and are now held by the Duke of Devonshire.

The Blennerhassetts, ,Conways, Herberts and John Stone, John Harding, and the Countess of Mountrath, in right of her husband, who died before he was ‘rewarded,’ all were settled on those confiscated estates. John Stone was married to the daughter of his cousin, John Chapman. She was co-heiress with her two sisters, to each of whom John Chapman promised a £5,000 fortune. The sisters all died childless but the sons-in-law, especially Stone, insisted on getting the promised fortunes so it was that, to satisfy their demands, James I, John Chapman, was compelled to sell his Kerry estate which he did, to Lord Cork, for £24,000. John Chapman died shortly afterwards at Youghal.

The second brother, William Chapman, had a son, who sold his share between Mr Bateman and John Holly, afterwards migrating to county Meath, where he became ancestor of the present baronet of that name. There were 4,422 acres in this grant, some of which is today in Mr F Bateman’s hands, part of it having been sold some forty years ago to the late Maurice Sandes, is now in possession of his nephew, Faulkner Collis-Sandes, who took the latter name on becoming his uncle’s heir. John Holly’s family have long since disappeared from Kerry.

To the list of English settlers at the beginning of the 17th century may be added Springs, Chutes, Raymonds, Morrises, Guns, and Staughtons, all of whom were planted in Kerry in the reign of Elizabeth.

Queen Elizabeth’s settlement of Munster, date 27 June 1586, was on the following lines: ‘The forfeited lands were divided into Seignories to contain 12,000, 8,000, 6,000 or 4,000 acres each, exclusive of bog and mountain, to yield to the Crown for first-class plot £66 12s 4d and so proportionately the lesser ones. This rent to be abated to half for the first six years, during which time undertakers were to be permitted to import all the commodities they needed from England duty free. No man (excepting by special license) was to have more land granted to him than 12,000 acres, nor to marry mere Irish.

The last rebellion was said to have been caused by these intermarriages, hence this restriction. This order was a mistaken policy. We should have thought such intermarriages would have had a contrary effect. The grantees were ordered to people their place (now waste) with English, keeping on first class grant 2,100 acres for demesne, and so in lesser proportion for smaller grants. All arrangements were to be on a scale to correspond proportionally. Six farmers were to have lots of 400 acres each on the larger estates, six freeholders 100 acres each, and 36 families to have lesser portions – from 50 to 10 acres severally – on the lands of those who had received 12,000 acres.

Every freeholder was bound to furnish, for the Queen’s service, a horse and horseman fully armed; every grantee of 12,000 acres three horse and six footmen fully armed, each copyholder one armed footman. These men were bound to serve out of Munster, after seven years, at the Queen’s expense.

The descendants of the original lessees under this settlement still possessing the lands then granted are not many in Kerry. The terms of this Elizabethan settlement were never entirely carried out. These settlers followed the habit of their predecessors and intermarried with the Irish; moreover, they were friendly with those Irish who still survived, planting them as tenants under themselves on territories where the Irish had previously held powerful sway.

Again and again, disputes arose between the old and the new owners, these disputes being henceforward much intensified by the religious differences which were much accentuated by the many legal disqualifications which these continued uprisings entailed.

In due course, there was the rebellion of 1641, followed by a series of outbreaks, a shuffling and re-shuffling of estates, until ultimately a new settlement of the country was made at the close of the 17th century.[21]

It is apparent from old manuscripts that, generally speaking, up to the 17th century, Irish chieftains held full sway in their own districts. Certainly in McCarthy More’s district, his power was great, the ‘paramount power’ conferred upon the Earl of Desmond by the Crown being seldom exercised over him.

It is, however, evident that the ministers of the day astutely used the antagonistic interests – envy and jealousy of these potentates – to further the interests of the Crown in Ireland. Thus we find that in 1565, when Desmond’s power was becoming dangerous to the Crown, the McCarthy More, previously in disfavour, was forgiven by Elizabeth, created Earl of Glencare, and encouraged to watch and thwart the Earl of Desmond.

At the same time, the Earl of Glencare was kept in check by a new Crown settlement of his estates when evidently, under regal or legal persuasion, and probably pressed for money, he in 1588 alienated and sold some of his estate to a family recently come from England, namely, the Brownes, of Crofts, Leicestershire. This sale undoubtedly weakened the political power of the McCarthy More, and therefore reduced his importance as a friend to the Crown.

In the Carew MS, Lambeth Palace, there is a paper headed McCarthy More’s Right and Dues as Follows. This paper is said to be an inventory taken on the death of the Earl of Glencare. It shows how this property then stood. Here is a summary of its contents:

His Demean – Part he died possessed of; part in Florence McCarthy’s possession (Florence was married to his daughter and heiress); part mortgaged to Sir Valentine Browne, Kt; part disposed of to his (base) son, Donnel McCartie; part mortgaged to Mr Denny and Mr Hombuston; part disposed of to his base brother, Donogh McCartie. His Fisheries – fisheries belonging to Pallice, in Logh Lein, the Laune, in Loch Cara; those belonging to the Countess of Glencare; fishings belonging to the Castle of the Lough; fishings of the Castle of Carberry, via, in Valentia, possessed by Mr Denny and Humbustons; in Beginnis, in Nicholas Browne’s possession; in the Golen and Fartagh; the fishery in the Currane and the Ware, possessed by one James Meanye (Meagh, alias Meade) of Cork, merchant, by virtue of mortgage from the Earl of Glancare. Lands paying tribute to McCartie More (these were the freeholders, descended from the house of McCartie. All their lands lie in the Barony of Magunihy. They were bound to draw with garrons (ponies) the Earl of Clancarty’s wine from the Abbey of Killaha to the Garnduff in Palice. They were also bound to thatch the Earl’s house in the Garnduff but nowhere else), McFinneen’s lands, Clandonnell funs lands, Sloght More Cuddries lands, in Iveragh; Sloght Donnel alias Mac Teigue in Tough’s lands, being Glanleam, in Valencia; Slought Cormac, of Dounguilla lands, Iveragh; Clandermod’s lands, in Bantry; Clan Donnel Roe’s lands, Bantry; Sloght Owen More’s lands, Coshmange; O’Donoghue More’s lands, in Magunehy; O’Donoghue, Glanfleske lands (note, there are excellent ashen trees for pikes in this land); O’Sullivan More’s lands (note, these are the sept of the O’Sullivans, and were commonlie at warre with the Earl, and sought his weakening); McGillicuddie’s lands; McCrehon’s lands; O’Sullivan Beare’s lands; McFinneen Duff’s lands; Clan Laura’s lands (the Clan Laura sept were bound to guard the Earl of Clancartie’s carriages when he went upon anie excursion, and for that the eldest of the sept had of the best dish of meat that was set before the Earl when he was at meat during the journey). The Friary of Ballinskellig paid a sorren, or five marks of half faced money, at the Prior’s choice, value £4 8s 8d; the Priory of Innisvallen paid a cuddehy, or the like sum; the Archdeacon of Aghadoe paid a cuddehy, or the like sum; the Abbey of Killaha the same; the Abbey of Abemore the same. The sorrens of Dowhallo were paid by the MacDonagh, O’Kallahan, MacAulifee and O’Keeffe (note, AMR Dowhallow is in Cork, therefore these may be taken as Corkmen). Summa totals omnium Redittan execution es repra dida emmet Lcclsvij v x.

This summary shows how the Earl of Glencare had disposed of his property during his lifetime. It would be interesting to trace all the present possessors of these lands, but space only permits of a brief statement as to some portions thereof.

As has been stated, in 1588, the Earl of Glencare sold a portion of his estate to Sir Valentine Browne. At the earl’s death more of his estate was mortgaged to Sir Valentine and Colonel Nicholas Browne (his son). These were the Brownes from Crofts, Leicestershire, who came to Ireland in the middle of the 16th century. They should not be confused with the Brownes who came in the 13th century, who already possessed estates in Kerry, and with whom the newly-arrived Brownes very soon became matrimonially allied.

Sir Valentine Browne of Crofts was a much trusted ‘civil servant’ of Ed VI, also of Phillip and Mary. He ‘served his Sovereign in all parts of the Empire’ and in 1555, the last-named sovereigns sent him to Ireland as ‘Auditor-General.’ Sir Valentine died at his post AD 1567. He was succeeded by his son, also Sir Valentine, who was made ‘Commissioner for escheated lands in Ireland.’

This second Sir Valentine Browne was ‘occupied’ principally in Munster. His employment there gave him an opportunity of studying the capabilities of the country, and he wrote a masterly treatise, making useful suggestions to the Crown for the development of the county Kerry. Some of these suggestions are only now being carried out by the Congested Districts Board.

Sir Valentine Browne was a member of the Privy Council, AD 1585, but it does not appear that he ever resided on his Kerry estates as it recorded that, by permission of Sir Valentine Browne, Sir Edward Denny exercised all his privileges over his Kerry estate. When, however, Sir Valentine secured Lord Glencare’s estate in 1688, Queen Elizabeth ‘ordered’ Sir Valentine Browne to reclaim his privilege from Sir Edward Denny and henceforward to maintain his own armed force.

Sir Valentine’s eldest son, Thomas, married Mary Apsley, co-heiress with Joan (who married as first wife the first Earl of Cork), daughter of Annabel Browne and William Apsley. This Annabel Browne was daughter of John Browne, commonly called ‘the Master of Awney’ to whom belonged the Hospital Estates. This John Browne was one of the older 13th century settlers, his ‘Hospital Estate’ dating from 1226, when Geoffrey de Marisco founded the Hospital of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem – Knights Templars – at Awney in Limerick.

The lands belonging to this Hospital estate are noted – Patent Rolls, 2 James 1st, LXII-22, as ‘grants from the King to Thomas Brown Esq in Limerick’ and contain, with the ‘Entire Manor and Lordship, and preceptor or Hospital of Awney, amongst other properties, lands and castles in several counties, some in Kerry, namely ‘Ardarterie, otherwise Rattoo, Dingle, Bullin, Carrantabber and Knockgraffan, Minarde, etc,’ all these being ‘parcel of the estate of the late Hospital of St John of Jerusalem.’

Sir Nicholas, second son of Sir Valentine and Tomasina Bacon, brother of this Thomas Brown, had ‘his portion in Kerry’ of the lands purchased from the Earl of Glencare by his father. He married an Irish wife, Julia, daughter of O’Sullivan Beare. Sir Nicholas died in 1606, and left a large family. The eldest son, Valentine, being a minor, and (Patent Roll, 4 James I, 54) a grant was made to ‘Sir Geoffrey Fenton, Kt, of the wardship of this Valentine Browne, son and heir of Sir Nicholas Browne, late of Molahiffe, in Kerry Co, Kt, for a fine of £13 6s 8d ster, and an annual rent of £10 ster, retaining £3 6s 8d thereof for his maintenance and education in the English religion and habits, and in Trinity College, Dublin, from the 12th to the 18th year of his age: 30 Oct, 4th Regio,’

In 1611, this Sir Valentine applied for a remission of excessive Crown Rent (£113 6s 8d) reserved out of his estate. He obtained a reduction to £53 18s 6 3/4 d, and a confirmation of his grant on 28th May 1618 ‘for good and acceptable services performed to the Crown by the father and grandfather of the said Sir Valentine.’

Again, in 1637, his son, the second baronet, had a further patent for the better settling of his estate. But, notwithstanding all these settlements during the convulsion which ensued in 1641 and onward, these Browne estates had some curious transformations. We should remember that Sir Valentine, the 1st Baronet, had married first a daughter of the last Earl of Desmond, a portion of whose confiscated estate he had received from the Crown; secondly, a daughter of McCarthy, Lord of Muskerry, thus connecting himself with the two previous then deposed Kerry potentates. He appears to have ‘enjoyed his estate’ until his death in 1635.

His son had a more uneasy time and died in 1640. This son had married a sister of his father’s second wife, a daughter of McCarthy, Lord of Muskerry. Dying in 1640, just previous to the outbreak of 1641, his son, being an infant, took no part in public life so the estate was not forfeited. Thirty years later, 1670, this infant come to man’s estate, claimed and received from the Crown a remission of quit rent – unpayable during the disturbances.

This Sir Valentine was in high favour with James II who, in the last days of his power, 1689, created him Baron Castlerosse and Earl of Kenmare. The title then conferred remained for some time in abeyance as on the deposition of James II, Sir Valentine and his son, Colonel Nicholas Browne, were attainted for their allegiance to the king. The father, Sir Valentine’s estate, was confiscated, but Colonel Nicholas Browne, not being esteemed so guilty, a grant of £400 per annum was made from his estate for his wife and family. The title, however, conferred by King James, was not officially recognised in England until George III ‘recognised’ rather than created Valentine, reinstated as 5th Viscount and Earl of Kenmare. This nobleman is described as ‘having distinguished himself under trying circumstances.’

John Asgill

During the attainder of Colonel Nicholas Browne aforesaid, these estates had a curious transfer. Jane Browne, daughter of Col Nicholas (2nd Viscount) married a stranger from London. This stranger was a clever lawyer, who came to Ireland to ‘push his fortune.’ He was named John Asgill, was officially employed in the Court of Claims (where he could take a general view of all confiscated estates), and immediately married Miss Browne. He was elected MP, and as ‘trustee’ purchased many of the confiscated estates, amongst others the Kenmare estate, ostensibly in trust for his young brother-in-law, Valentine Browne.

John Asgill is thus described (in 15 Report, Records of Ireland, page 332):

18 April 1703, John Asgill of Dublin Esq, of the Manor of Rosse, with many other lands etc, in the County Kerry etc, the estate of Valentine Browne and Nicholas Browne, Viscount Kenmare attainted, to hold as in the deed limitted.

John Asgill appears to have ignored the ‘limittations’ and at once to have assumed the rights of complete ownership, as we find on October 30 1703 that ‘Anthony Hammond, as guardian of Valentine Browne, petitioned the House (Irish parliament) setting forth that John Asgill, as Counsel, and Murtagh Griffin, as Agent, had purchased these estates from the trustees for said Valentine Browne, and, in breach of the trust reposed in them, do now refuse to convey the same.’

Evidently, John Asgill fought hard to keep possession, as, on November 10 1703, the parliament refused this petition, thus leaving him in possession of the estates which he would probably have hereafter ‘enjoyed’ but for the following curious incident. Previous to coming to Ireland John Asgill had written a book in which he published some very legally argued but absurd religious views. It is said that the book created a great sensation and that to escape the penalty then in force of trial for blasphemy, John Asgill came to Ireland where his undoubted ability procured employment. Be that as it may, it being now important to humble John Asgill, a copy of the book was obtained and transmitted to Ireland. In the Irish parliament, John Asgill, as author of this dangerous book, was tried and convicted of blasphemy, principally on the following extract:

Having pursued that command, seek first the Kingdom of God, I yet expect the performance of that promise, to receive in this life an hundred -fold, and in the world to come life everlasting. I have a great deal of business yet in this world, without doing of which Heaven itself would be uneasy to me … but when that is done, I know no business I have with the dead! and therefore do as much depend that I shall not go hence by returning to the dust, which is the sentence of that law from which I claim a discharge but that I shall make my exit by way of translation which I claim as a dignity belonging to that degree in the science of Eternal Life, of which I profess myself a graduate … if after this I die like other men, I declare myself to die of no Religion![22]

Being found guilty of blasphemy, John Asgill was expelled from the house and outlawed. Thereupon the 3rd Viscount Kenmare, having been an infant when his father and grandfather were attainted, his friends claimed, and he was allowed to plead himself ‘innocent’ whereupon the estates now confiscated from Asgill were ‘settled’ upon him by the Trustees of Forfeited Estates. Since then those estates, some of them dating so far back as the 13th century, are held by the Earls of Kenmare.[23]

Herbert of Castleisland

Charles Herbert, a gentleman from Wales, received 3,768 acres at a Crown rent of £62 15s 4d per annum in the neighbourhood of Castleisland. This Charles was succeeded by his son, Giles Herbert, who had a re-grant of these lands on similar terms (10 James I) as was in the original grant of Elizabeth to his father, Charles.

Giles Herbert sold his lands to Blennerhassett of Ballyseedy, and died childless. Sir William Herbert of St Gillian’s in Monmouth (a different branch of the family to which Charles Herbert belonged) had 13,276 acres in Kerry at a Crown rent of £221 5s 4d per annum. Sir William does not appear ever to have attempted to settle in Kerry. He, too, died without male issue. This Sir William Herbert was the second son of William, Earl of Pembroke. He had a daughter who married the famous Lord Herbert of Cherbury who was her cousin. This branch of the family were afterwards represented by the Earl of Powis.

Sir William Herbert, of St Gillian, had a brother, Sir Richard Herbert of Colebroke, from whom descended Lord Herbert of Castleisland. In AD 1656 came Thomas Herbert of Kilcow, who was the first of his name settled in Kerry. He, too, descended from Sir Richard Herbert of Colebroke and was sent over and largely enfeoffed with portions of the lands originally granted by Elizabeth to Sir William Herbert by his brother or cousin, Lord Herbert of Castleisland, who had inherited from the original grantee. Part of the lands appertaining to the original grant to Sir William Herbert passed to his daughter, Lady Herbert of Cherbury. This portion was later on demised by fee farm grant by Lord Powis to six lessees, known as ‘the six gentlemen.’

The representatives of these ‘six gentlemen’ or their assigns, hold those territories today unless such portion as have been sold under recent Land Purchase Acts to the occupying tenant.

The ‘six gentlemen’ originally were granted this fee farm in common; but in the early part of this century these lands were divided by Act of Parliament in shares between the representatives of those ‘six gentlemen’ to whom Lord Powis had originally demised those lands. The divisions made by Act of Parliament were to the following gentlemen: Herbert of Muckross, the collateral descendant of original lessee had first portion, Blennerhassett of Ballyseedy had second portion, which portion was willed by Mr Blennerhassett to his daughter, Lady Headley. This portion therefore appertains to the Wynne estate. The third portion was given to Crosbie of Ardfert who assigned his share to Mullins (Lord Ventry) retaining to himself the right of advowson. The fourth portion went to Crosbie of Tubrid, whose daughters, co-heiresses, were married, one to Colonel Berkley Drummond, and the other to Major Charles Fairfield. Both of these ladies died childless. Mrs Drummond, the surviving sister, willed this property to her husband’s nephew, Mr Drummond, whose son is the present owner of Mounteagle. The fifth portion went to Fitzgerald, Knight of Kerry, who assigned his share to Chute of Tulligarron (Chute Hall) willing the advowson to Mr Townsend, of Castletownsend in the county Cork. The sixth portion rests with Mr Meredyth of Dicksgrove, who descends from the original lessee – a lessee brought forward to the five above-named potentates, when the Earl of Powis, having agreed with them, desired to vest the remaining portion in ‘a good and true man.’

A share of the Powis estate in Castleisland was sold to pay the expense of this Bill of partition. John Markham Marshall purchased this share, intending thereupon to carry out certain useful public works. Mr Marshall died in the prime of life before he had time to carry out his good intentions. He endeavoured to secure a resident owner, as by his will the possessor of this estate is bound to reside in Kerry for three months each year on pain of forfeiture. Mr Marshall bequeathed his purchase to his aunt, the wife of Sir John Franks, Kt, for her life, with remainder to his brother-in-law, the Honble Mr Leeson, whose grandson, John Markham Leeson Marshall, now holds this portion of the lands originally granted by Queen Elizabeth to Sir William Herbert of St Gillians.

Sir Edward Denny

Another of the Elizabethan settlers was ‘Ned Denny.’ He obtained his grant as a reward; in other words, as payment for arduous military service in Ireland. As Fuller, the historian, puts it, by ‘God’s grace, the Queen’s favour, and his own merit, Edward Denny achieved a fair estate in Ireland’ namely, ‘the seignory of Denny vale with the Castle of Tralee, stated as being the principal seat of the Earl of Desmond in those parts.’

The grant of Elizabeth to ‘Ned Denny’ was 6,000 acres which included the shire town of the county together with the advowsons of the parishes belonging to the suppressed abbey of Tralee. By inquisitions afterwards taken the possessions of the Dennys were shown to be largely increased by grants of Lord Kerry’s land, forfeited in or about 1600. The Sir Edward Denny who was granted these estates by Elizabeth did not settle in Kerry. Times were disturbed. He was one of the Council of Munster, a trusted soldier and adviser to the Lord President. When the fear of invasion obliged Sir Thomas Howard to strengthen his fleet on the south coast of Ireland, the ships sent to help him sailed ‘under the instructions of Sir Edward Denny.’ Sir Edward died and was buried in England. He lies beneath a stately monument erected in Waltham Abbey, Essex, by his widow, Margaret Edgecombe. Waltham had been purchased from King Edward the VI for £3,000 by Sir Edward Denny’s mother, Joan, daughter of Sir Philip Champernowne of Modbury in Devonshire. Inscribed on the tomb is the following:

The Right Worthy Sir Edward Denny, Kt,

Son of the Right Honble. Sir Anthony Denny,

Counsullor of State and Executor to King Henry the Eight,

and of Joan Champernowne, his wife, who, being of

Queen Elizabeth’s Privy Chamber and one of the Council of Munster in Ireland,

was Governor of Kerry and Desmond, and Colonel of certain Irish forces.

He departed this life, about the 52 year of his age, on the 21 of Feb 1599.

Learn, Curious reader, ere you pass,

What once Sir Edward Denny was,

A courtier of the chamber,

A soldier of the field;

Whose tongue could never flatter,

Whose heart could never yield.

There is also a long history of Sir Edward’s work and virtues inscribed on this tomb, which is in fair preservation. In this same church was buried the body of King Harold, who was the founder of Waltham Abbey.

Dame Margaret Denny lived a widow for 48 years, dying 28th April 1648 aged 88. She was buried at Bishop Stortford Church, Herts. Sir Edward was succeeded by his son Arthur, who lived at Cahernafeely (near Chute Hall). Sir Arthur lived in troubled times. He had great difficulties in ‘settling’ his country from which he got no returns so that he could not pay his Crown rent. In the Rolls Office, there is a King’s letter remitting all arrears of Crown rent due by Arthur Denny or his father leviable off his Kerry lands. There is also an order that Arthur Denny surrender all lands not seignory lands and have a new grant of the same. This is dated 30th December to James I.

On the 20th September 1604, Sir Arthur Denny had a remittance of all Crown rent from the date of Michaelmas 1598. A like remittance was given in 1609. Another trying incident in this Sir Arthur’s career, the documentary evidence of which remains, was the claims of Mr Randall (widow) against Cahernafeely made after Sir Arthur had expended £500 in ‘making there a house.’ Sir Arthur was then too ill to defend his interests so he petitioned the Council to give him time to defend his right, and his petition was backed by the following influential names: G Cant (Archbishop of Canterbury), E Worcester, James Hay, Edmonds T Suffolke, G Carew, W Wallingford and Ralph Winwood. There is an inquisition, 13th April 1613, which finds Sir Arthur Denny seized in fee of six ploughlands of Tawlaght, the Abbey of Tralee, held under letters patent to his father, Sir E Denny, by Elizabeth. It is found that the friary of Ardfert (Ardart) and certain lands in county Kerry were then in possession of Edward Grey Esq (cousin of Denny’s) and his assignees who held the same under the title of the said Arthur Denny Esq and Sir Edward Denny Kt, his father, being parcel of the seignory of Denny Vale. Sir Thomas Harris (who afterwards married Arthur Denny’s widow) held Ballyvoylan and the Rectory of Ballinhagillsie (Ballinhaglish) as tenant under a grant to Edward Denny (27th September, 29 Elizabeth).

In the Chief Remembrancers Office there are some curious facts recorded of those early times. Amongst them we find that at Easter term 1628 the Crown had a case against Sir Edward Denny for holding a ‘manor court and fair at Tralee.’ In defence Sir Edward pleaded his patent (25th June, 6 Charles I). In Hilary term, 1638, the Crown again had informations against Sir Edward Denny and also against the Borough Corporation of Tralee for receipt of the four and twentieth part of a gallon full out of every Bristol band barrel of grain sold in Tralee market. Again, Sir Edward pleaded the above-mentioned patent, which is still preserved in the Rolls Office. In the year 1632, James Ware and Gerald White conveyed the lands and fishing of Ballyvoylan to Sir E Denny (these lands and fishing must have been underlet by Sir T Harrison to these two, probably when he married and went to reside at Cahernafeely with Sir Edward’s mother).

In the war of 1641, this Sir Edward Denny, grandson of Elizabeth’s grantee, took active part under the President of Munster, the first Lord Cork, and was a heavy loser. His new castle at Tralee, defended by his stepfather, Sir Thomas Harris, was besieged, taken and wrecked by the Irish.

Sir Edward’s wife and family fled for refuge to England where they were reduced to great distress. In those days many ‘distressed Irish ladies’ existed. Amongst others are given the names of Lady Ranelagh, Lady Kildare, Lady Blaney, and Lady Denny, all of whom were ‘ordered’ relief by parliament. Apparently, this relief was not always paid as parliamentary records show that on the 14th January 1650, it was ordered by parliament ‘that the Commissioners are to pay Lady Denny the arrears of weekly allowance granted by former order of the House on 25th December 1646.’ Again, in 1662, we find ‘Dame Ruth Denny, wife (widow?) of Sir Edward Denny, Kt, who hath lost her husband and whole estate in Ireland, and who hath a charge of many children ready to perish, to have £100 for her present support and relief.’

In this same year, 1662, the following Kerry names appear amongst the surviving ’49 officers’ who received help, Sir Arthur Dennie (Denny, son of the above Dame Ruth), Major Wm Crosbie, William Crosbie and Arthur Blennerhassett. At the ‘settlement’ of 1688 the Denny family was amongst those found ‘attainted’ by James the Second’s parliament; they were reinstated.

In the Commons Journal (Ireland) 27th October 1698, we find the following entry – ‘Motion of behalf of Edward Denny, a member of this House, praying that he may be relieved against Sir James Cotter, who had done him several injuries in the late troubles, whereby he (Edward Denny) had suffered to the value of £6,000.’

Order was made, ‘That a committee do examine and report on the same.’ On 28th November 1698, ‘Report of Committee – Agreed that Sir Edward Denny’s mansion at Tralee was maliciously burned by Sir James Cotter on the 24th August 1691; that Sir James Cotter being adjudged within the articles of Limerick, there is no other way to relieve the said Edward Denny but by Bill.’

Ordered, ‘That a Bill be prepared by the said Committee accordingly.’ On the 2nd December 1698, Sir John Broderick, on part of said committee, reported the heads of a Bill for the relief of Edward Denny.’

In the middle of the 18th century, the Denny family divided into two important branches, one in this county, the other at Castle Lyons, Co Cork – two brothers marrying the Ladies Ellen and Catherine Barry, daughters of the 1st Earl of Barrymore.

After about three generations, the two branches were again united when Sir Barry Denny, 1st Baronet, created 1782, married his cousin Jane, daughter of Sir Thomas Denny, KT, who died without male issue. Sir Barry’s next brother, Edward Denny, married Miss Rynd of Co Fermanagh, an heiress, and went to reside in that county where the family remained and multiplied for generations.

The following letters written by Mrs Blennerhassett from Bath to Jane, Lady Denny, are amusing, and throw a light upon the fashion of the day which is interesting:

November 17, 1770

My Dear Denny

Tickets kept up so high ever since that Atty (her husband) would not buy until today, which, being the last day before the drawing, made it necessary to obey your orders, and accordingly he purchased two (tickets) at £14 10s each. The numbers are 14328 and 2247 – oh, that once in our lives we may be lucky to you! Next Monday, the 19th, they begin drawing, and should fortune smile you shall soon hear from me … The tickets being bought I would not omit writing, but time will only allow me to add our love, and that I am, dear sister, affectionately yours,

J Blennerhassett

November 24, 1770

My Dear Denny

I have wrote to you twice so lately you will, I fear, grow tired of receiving my letters. However, perhaps you’ll pass this one trouble by, and indulge your old Misis who dearly loves corresponding with you, and particularly when she can pick up anything amusing or interesting to impart. Nobody alive should have wrote to you today but myself – no, not even my beloved Rat (her husband). No, sir, I won’t let you take the pen from me. I wish my friends as well as you can, and if there is a lucky event in the family why should I not tell it them. Now you think Jenny (her daughter) is going to be married; not a bit of it; but to be sure you’ll think it a good thing. In short, you have got twenty thousand pounds. Yes, my dear sister, it came up yesterday – 14328, and I will be the happy channel to convey this pleasing news. I only wrote the foregoing page to prepare you to hear this glorious event, which has really near turned my head for joy. I got up and danced about the room, very near broke all the breakfast china, frightened Rat, who harmlessly read in the papers that such a ticket was drawn yesterday. Words are far too short to express what I feel on this occasion. We will not mention a word until we hear from you, as it would cause us infinite trouble – drums, boys coming for money, clerks from the office, etc. We beg by return of post a letter signed by all who may be concerned in this dear ticket, with orders what to do, as there are necessary expenses always upon these occasions. A friend of ours, Member of Parliament, had such a prize last year. From him we might know the customary forms, as I daresay the sisterhood will wish to do what is right – and I hope to God it comes to you or them, tell me your share in the ticket. The ticket is not registered, so no one can know where it is, and the secret lies between us and our children, who are running wild for joy; that you may live to enjoy it in health and happiness for many years is our sincere wish; and that it should be a means of bringing you once more to England would be the greatest satisfaction to my dear Denny – Your most affectionate,

J Blennerhassett

Our love and congratulations to the sisters – duty to our good father. We have examined at the State Office before we send you this good account. We think it would be very prudent to keep the contents of this letter a secret, as many inconveniences must arise from divulging it.

This letter is addressed ‘to Lady Denny, at Listrim, near Tralee, County of Kerry, Ireland.’ It will be evident from this brief outline that the Dennys ‘settled’ in Kerry by Queen Elizabeth, had a chequered career. Nevertheless, despite losses, attainders, the fortunes of war, and many ups and downs, their property in Kerry remained in the possession of that family for three hundred years.

The late baronet, Sir Edward Denny, never married; he lived for many years in London where he recently died, aged 90. He was succeeded by his nephew, the present baronet, on whose succession the Denny vale estate was sold under Land Purchase Act to the tenants. During the time the Dennys were in possession of the estate, the shire town, Tralee, grew from a group of mud cabins to the handsome town we see today and the county generally evolved out of vast empty waste, described as ‘devoid of man or beast,’ to a fairly well populated district.[24]

Elizabeth I

In Elizabeth’s reign a change came which henceforward made a decided cleavage in religious matters. It was then ordered by law that in future the service of the Reformed Church of England should be the religion of the State, and the State endeavoured to stamp out the Church of Rome by legal enactment, all men being ordered under penalties to conform to the State Church. When parliament and English law was established in Ireland, those laws were only ordered for ‘the English in Ireland,’ the English then mainly living within ‘the Pale’ which was principally in Leinster, all outside ‘the Pale’ remained under Irish custom. As the English spread through the country they brought their laws with them, using English law or Irish custom in their dealings with the Irish, as best suited their individual purpose.

This diversity of system created immense confusion in the country and much suspicion and jealousy in the minds of the people. The outcome of this complex and contradictory proceeding was much injustice. Elizabeth added to the difficulties by the introduction of this religious grievance, which henceforward accentuated and embittered every difference.

The great lords thought more of securing their own position than of improving the country. Improvements to men of the middle classes, meaning an increase to their individual wealth, power or importance, without any consideration of how their proceedings affected the rights or feelings of others. Selfish human nature eagerly accepted and fomented the religious difference as a means whereby they could secure some individual or party benefit.

Ill-will between contending parties presently culminated in the rebellion of 1641, when the older settlers, grown more Irish than the Irish themselves, played upon the passions of the people, and rose to repudiate the newcomers with their customs, laws and religion. The idea of these men appear to have been to secure undisturbed possession or the country for their individual aggrandisement.

Together they fought, Settler and Celt, to oust the Elizabethans, and thus secure to themselves the lands and possessions which the newcomers had obtained. Then came Cromwell. Cromwell was on the side of those whom Elizabeth had planted. There was another conquest and redistribution of estates amongst the conquerors. When this rebellion of 1641 broke out an Act of Parliament was passed (17) Charles I, declaring ‘the lands of all those engaged in rebellion should be forfeited to the King without the formality of an inquisition.’ It is computed that two million and a half of acres were so seized and assigned by Charles’s parliament to those who advanced money or adventured themselves in the ‘Reduction of Ireland.’

The following list thus made of lands seized and valued, is instructive:

Land in Ulster, portioned to yield £200, at 1d quit rent per acre

Land in Connaught, portioned to yield £300, at 1 and a half d quit rent per acres

Land in Munster, portioned to yield £450, at 2 and a half d quit rent per acres

Land in Leinster, portioned to yield £600, at 3d quit rent per acre.

When Cromwell’s army was disbanded in 1653, this Act of Charles I, as well as the following one of Cromwell’s, was utilised to pay the army, all of whom had been without pay since 1641. Commissioners sat at Athlone and Loughrea to administer the laws of settlement, Cromwell’s addenda to Charles’s Act being to the following effect:

First – All persons guilty of overt act of rebellion and who had not ‘submitted’ within 28 days, with all priests and Jesuites, to be excepted from pardon in life or estate.

Second – Those who had commanded in the rebellion were to relinquish two-third of their estate, their wives or children to be given an equivalent grant of one third in whatsoever place parliament appoints.

Third – All Romanists who had not shown ‘good affection’ to parliament were to forfeit one-third of their estate, and to receive two thirds wheresoever parliament shall appoint.

Fourth – All persons who had not, as occasion offered, manifested ‘good affection’ to the parliament were to forfeit one-fifth of their estate. These terms may fairly be called penalised regrants. Most of the disaffected were portioned in Connaught where they were cut off from the outer world by what was termed ‘the mile line.’ That is to say, no grant was to be within a mile of the sea or the Shannon because intercourse with others was easy by water. Hence the origin of the old saying, ‘Cromwell’s choice – to Hell or Connaught.’

Staughton and Raymond

Amongst the Elizabethan settlers in Kerry were Anthony and John Staughton, ‘Keepers of the Castle or Star Chamber’ (tempo 4, James I). Anthony married a daughter of the Earl of Thomod, sat as MP for Askeaton 1613, and received lands in Kerry in the following somewhat roundabout fashion.

Upon the first suppression of the Abbey of Rattoo the lands were leased to John Chapman, with reversion to the Crown (31 Elizabeth). Long before this lease expired, namely, 39 Elizabeth, 24th January 1597, we find these lands given by the Crown to George Isham, of Bryanstown, Co Waterford. Yet, again, six months after, namely, 28 June 1597, the Crown bestowed these same lands on the ‘Provost and Fellows of Trinity College, Dublin.’

Five years later, these same lands were granted by the Crown, in 1604, to Sir James Fullerton who passed them to Anthony Staughton in whose possession they were when he died in 1626. They are still in the hands of the representative of the Staughton family.

In connection with the Staughtons came the Raymonds. Samuel Raymond was a clerk of the Star Chamber. By patent (15 James I) 1617, he was made Comptroller of Customs in Limerick, Youghal, Dungarvan, Kinsale and Dingle-y-coussa. In Dingle was his first possession. They he leased Ballyloughran, which was afterwards purchased in fee by his descendant. Among the estimates for Civil Service in Ireland, AD 1636, in the MS Report, Birmingham Tower, Dublin Castle, there is an entry, ‘Samuel Raymond, Comptroller of the Port of Dingle – his fee to Michaelmas, £17 15s 6 (.75) d.’

This Samuel Raymond, in 1613, was complained to the House of Commons (Ireland) by Robert Blennerhassett MP for serving him with a ‘process of the Star Chamber’ at the suit of ‘one Gray.’ Raymond was punished, apparently for infringing on the principle of parliamentary inviobility by a nominal fine.

Samuel Raymond’s son, Anthony, was a close friend of Lord Kingston, who left his guardian to his sons. It is said by some of Lord Kingston’s descendants that Anthony Raymond made use of his position to unfairly secure some of the ‘minor’s’ Kingston estates. Be that as it may, several portions in Kerry patented to Lord Kingston under the Act of Settlement did pass to Anthony Raymond from whom descended the Raymonds of Dromin, Ballyloughran, and Riversdale, all of which estates are now much reduced, being leased in perpetuity at low rents to other families. The Morris family were closely connected with the Raymonds. They held together leaseholds of the possessions of ‘brave Maurice Stack’ who was basely murdered by order of Lady Kerry.

Walter Talbot, Maurice Stack’s brother-in-law, took charge of the infant, Joan Stack, and her estate. He, on behalf of his niece, rented part of Stack’s estate to the Raymonds and Morrises. Later on Joan Stack married Brian, brother of Bishop Crosbie, and her descendant, Walter Crosbie, sold the fee simple of the estate to the occupying tenants – Raymond and Morris.

In 1688, Mr Morris and his family were obliged to fly to England, whereby he had heavy losses. General Ginkle mentions the loss of real estate to Mr Morris at £500 a year. When times quieted Mr Morris wrote to his relative, Sir Robert Southwell, asking to be made Sheriff of Kerry. He says, ‘I am informed no one has it yet, as I suppose you do not question but I shall serve the King faithfully, so I hope you will be of so considerable an advantage to me as to make me some amends for the great damage I have sustained in the Revoliution.’

Mr Morris was married to a sister of Lord Southwell’s, who was head of the Irish branch of the family. Between 1598 and 1641 – also between 1641 and 1660 – there was an influx of new people to Kerry. Some were called ‘adventurers’ – those who advanced money, or aided in the war, and were paid by some of the confiscated land ‘the forty-nine officers’ being those Protestant officers who had served the king before 1649 but who were not serving with Cromwell or rewarded by him. The claims for pay and losses of these forty-nine officers was a very serious item, amounting to £1,800,000.

Amongst those who took arms for the king in 1641 and forfeited are six MacCarthys – Daniel of Carrigprehane, Florence, alias Sugane (Sugane being a title to designate the prince succeeding the last Sugane Earl of Desmond), MacCarthy of Ardtully, Killowen, Tiernagoose (Dicksgrove), and Drumavally. There was also O’Sullivan More with his uncles, Colonel Dermod and Philip O’Sullivan. The O’Sullivan More, secure in the fastness of Glenbeigh and Ballybog, continued to hold out after others had ‘come in’ and settled. Another distinguished Kerryman who took an active part in this war, whose estates have vanished, was Colonel McElligott, who held Cork against the parliament army. Besides these there was Pierce Ferriter, of Castle Sybil; Walter Hussey of Castlegregory; Garrett Fitzgerald of Ballymacdaniel; The O’Donoghue More of Glenflesk; and the McGillycuddy of the Reeks. All these forfeited their estates for ‘having taken arms for the King’s prerogative against the King’s Government.’

This strange indictment shows what a curious state of affairs conduced to that rebellion. Many of these men were reinstated to a portion of their estates. Another remarkable feature of the rebellion of 1641 is the fact that families were divided – one for ‘the king’ the other for ‘the government.’ Lord Kerry was Governor of the County which he held for the government.’

Some of his brothers, nephews, and cousins were for ‘the king.’ This brought Lord Kerry into some difficulties. The arms provided by ‘the government’ and entrusted to him for the defence of the county were abstracted from his charge and used for ‘the king’s’ service. It is evident the conduct of his relatives irritated his lordship, who writes thus of his half brother, Edmund Fitzmaurice, of Tubrid: ‘I do not expect any good end of that broode – they have showed themselves the most con-natural that have ever been heard of, and they will have such a reward as I do not wish them. They have I believe enriched themselves on mine and others spoyles and will all flee the country with Taaffe’ (the commander of the king’s troops).

On the 30th November 1660, Charles II’s Act of Settlement was passed. It was then described as ‘Magna Charta Hibernie’ and may now be termed the ‘Title Deed of Ireland’ inasmuch as it passes as the ultimo ratio of all enquiry into title.

When Cromwell made his settlement, commissioners sat at Athlone and Loughrea for the purpose of carrying out his arrangements. The Roman Catholics were naturally slow in obeying his order to ‘come in’ and relinquish their estates and take their allotments in Connaught. Thus it came that when Charles II was restored and enacted his settlement, many Roman Catholics had not responded to Cromwell’s edict.

A misfortune fell upon them which was not anticipated by those who prepared the Act of Settlement. Their estates were confiscated by Charles the First’s Act of 1642; they had not got fresh status under Cromwell’s settlement and were therefore deprived of all estate, their old ones being vested in the Crown.