In September 1840, the Castleisland correspondent of a newspaper recorded the accidental death in Canada, by a fall from his horse, of Lieutenant Robert Adolphus Lynch:

His premature death, for he was yet unvisited with the hoar of age, will be a source of great and lasting regret to the circle of friends whom his literary attainments and social qualities collected around him in this country. His principal, and we believe, his only published work is that excellent and humorous guide to our own lakes which contains so many amusing traits of local peculiarities and abounds in so rich a collection of the wild legendary lore belonging to the district.1

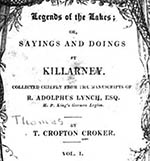

The ‘excellent guide’ alluded to was Legends of the Lakes (1829) by Thomas Crofton Croker.2 Lynch had supplied the material for the book and Croker, who had recently published Fairy Legends and Traditions, arranged the work into a narrative.3

The book had been in progress since early 1827 when Lynch, whose address was Garden Lodge, Killarney, had supplied his Kerry Legends to Croker via his friend, Mr Sainthill, and his cousin, Joseph Humphreys.4

Croker was clearly impressed with the material and Lynch gave him liberty ‘to do as you please with my manuscript’, adding, ‘as to my achieving equal fame with you I believe there is no chance of that, neither do I intend to strive for it; nevertheless, I consider the temple of fame sufficiently large to afford me an humble niche‘.

In 1827, Lynch was a married man supporting a wife and young family. He had been retired on half pay from the King’s German Legion since serving in 1814 and 1815 and was seeking an alternative career in order to educate his children.5

However, 1827 was not an entirely good year for Lynch, as revealed in his correspondence with Thomas Crofton Croker.6 He was financially constrained and therefore anxious for publication of the book. He had also sent Croker a poetic tale entitled Sir Ronayne of the Lakes, a work on which he placed great value. 7

Croker, writing from the Admiralty in London, was slow to respond to Lynch’s impatient letters.

In September, Lynch requested that reply to his correspondence be directed to him at the Claremont Institution in Dublin, the master of which was his cousin, Joseph Humphreys. Lynch had travelled to the city to tend his sick mother. He wrote again in October to enquire if Croker had received papers he had left for him in Cork on his way to Dublin. His mother, he said, had now passed away.

Lynch believed he had a talent as a writer and felt ‘bound to make as speedy and as good a use of it’. He asked Croker if he could help him find work in this field in London.

An encouraging reply was received for Lynch’s next letter was full of enthusiasm, and detailed how he would prepare another 300 pages by the first of March 1828: ‘I will visit the places to be described and render them as correct as possible, you can retouch the whole’.8

Lynch despatched more work to Croker but as time went on without reply, he began to feel less confident about seeing his work in print. He decided to go to London in March 1828 to try himself to get his writing published. He informed Croker of his intentions and asked for the return of the tales already sent. Despairing, he included an epistle in an effort to be heard:9

To my good friend T C Croker Esq Wide o’er the world wild winter sweeps, Dark o’er the hills the sad mist creeps, Loud roars the wind, deep gloomy the sky, In wrath the storm-fiend passeth by. The withered woods are swept at lest; Like skeletons amid the blest; They clank their bare army – and the rain Descends in torrents on the plain. Wild heavy the lake against the rocks, Whose surging caverned echo mocks; And nature from her mountain throne Breathes o’er the whole a lengthened groan. A kindred gloom my spirits take, And when I seek my harp to wake, Come moans for music, and a sigh For its sad master’s destiny. It is not so in summer hours, When nature wreaths her brow with flowers; Tho’ small the minstrel’s store I ween, Forgetful of his fate, the scene Delights him, and the leafy grove Attunes his heart to peace and love. Now – darkening day, and lengthening night, Has little share of pleasure bright, And oh in vain the minstrel sighs, For balmy breeze and summer skies. I wake – I turn – and sleep denies His leaden scepter to mine eyes, While thoughts like troubled waters roll, And sweep across my saddened soul. First fell despair with hollow eyes Appears, and thus terrific cries:- ‘To thee an humble son of song, To thee, I say what hopes belong? Aspiring to a poet’s name, How canst thou hope a breath of fame? When mighty names can hardly keep Possession of her slippery steep. Where is thy patron’s partial hand To help thee, struggler, to the land? Or grant that thou couldst gain the post, How small to thee the empty boast! Thy help has not a golden string, And fame is but an hungry thing. But even if thou dost think it good, Say will thy children love such food No! – thou must still contend with sighs, And hopes, and tears, but never rise; While they, – when thou, or soon, or late, Shalt die – must share an equal fate; For know I mortal! Thou, and thine, Are marked by me, and ye are mine.’ The monster ceased – for prudence came, To calm my vex’d and fevered frame; ‘Hold fast thy hope, and truth,’ she cries, ‘Nor sink thus low, arise! Arise! What if thou hast not fortune’s smile? She can but rage a little while, And lo! Where age, and death appear, To teach thee all thy duty here.’ She spoke! – And age came trembling on, Death-tracked, his voice was almost gone; Yet still he whispered in mine ear, ‘Oh mortal! Why heap treasure here; Treasure not worth a moment’s care, For know we all but travellers are, Through this sad world a little apace, and go, where riches find no place.’ Age paused – for death wide open threw His gates – an ill-wind whistled through; Then thundering spoke, these words of fate, ‘There is no passage but this gate; Prepare! Prepare thy last account, ‘Ere death has dried life’s bubbling fount.’ ‘Tis thus on every hand assailed, With drooping heart, and spirits quailed, My soul from this sad season takes Its colour and my harp awakes A moaning music, and I sigh In vain for summer’s cloudless sky. Oh come sweet summer! Swiftly come! And take me to thy leafy home, Return my help, return my voice, And bid thy minstrel’s heart rejoice. ‘Tis thus unskilled to court the great, The poet feels his helpless state, And knows, that hatred never paid A fee per curse, than wisdom speaks In vengeance, with a withering look, And wished his foe might write a book. For thee my friend! Whate’er my fate, May fortune still on thee await, To thee, oh may thy season bring Fresh joy repose its stormy wing, For thee, regardful of my sighs, For thee, may many such arise; And may’st thou never, never know, The ills these lines but feebly show.

By August 1828, Legends of the Lakes was ‘in the press’ and Lynch had received payment from Croker. By the end of the year, Legends of the Lakes (in two volumes) was being reviewed and was on the bookshelves in January 1829.10 Lynch’s name, with Croker’s, appeared on the title page.

In June 1831, Lynch was miffed to discover that Croker had reissued the book without notifying him. He would not have then been aware that his name had also been removed from the reprint.11 He wrote to Croker from New Street, Killarney:

‘I find by the Cork Constitution that the Legends have gone into a second edition, to me this has been a surprise as I thought you might so far have regarded me as to consult me about a work with which to say the least I was so intimately connected.’12

The Croker correspondence reveals nothing about Lynch in the ensuing years until 1835, when he wrote to Croker that he was in London trying to arrange matters to emigrate. He was still struggling financially and sought a loan from Croker, who declined.

He looked to Croker for help in finding work in Ireland convenient for him and his family. Lynch suggested posts as Port Surveyor, ‘a situation formerly held by my grandfather’, or barrack master, or first class chief of police. He had heard that Lord Canterbury was going out to Canada and stated he would be happy if an official situation could be procured for him there. He would, he said, take anything that would enable him to educate his children.13

He was offered the port-mastership of Skibbereen, Co Cork but quickly resigned explaining that to do the job effectively, which involved a working day from 7am to 11pm, would cost him financially and was ‘incompatible with my interests’.14

During 1836, Lynch continued to apply to Croker for help in finding work and in September, he received a letter from the War Office about enlistment which if declined, meant loss of his commission. In desperation, he appealed to Croker, laying low his circumstances, which included a pregnant wife and severe financial difficulties. It was, in essence, a begging letter, from one gentleman to another. He asked Croker to destroy the letter when he had read it.

In October 1836, Lynch was in London on army affairs and seeking help in publishing an unfinished novel. He asked Croker if he was interested in legends from Glanerought in Co Kerry and if any number could be disposed of in magazines.15

By May 1837, Lynch had been gazetted out as ensign in the 63rd Regiment and with emigration still in mind, once again appealed to Croker for recommendations to persons in authority in Canada.16

One year on, Lynch had managed, by whatever means, to go to Canada. He informed Croker, ‘I have been in Canada where I have land.’ He had returned to Killarney because of the death by accidental burning of his second son, ’If you can be of any help to my family during my absence I believe you will.’

He asked for correspondence to be directed to him in Toronto. During this homecoming to Killarney, Lynch converted to the Roman Catholic faith.

This is the last we hear of Lynch until the notice of his death in 1840.

The family of Robert Adolphus Lynch

A sketch of Lynch’s family can yet be drawn, and no doubt he would have been proud to know that his children seem to have prospered in the world. Of his own paternity, however, little is known, though it is suggested he was a descendant of Thomas Lynch jnr (1749-1779), one of the signatories to the United States Declaration of Independence.17

Robert Adolphus Lynch married Johanna Almon, probably in Killarney,18 and the couple had at least six children, three sons and three daughters. All three daughters married.19 His sons were Robert Adolphus, born in Killarney in 1828, and Edmund, born in 1837 (the name of the son who died in 1838 is not known). Robert and Edmund laid roots in America. Robert married Anna, daughter of John and Anne Cahill and died in Haverhill, Massachusetts on 13 June 1902.20 Edmund married Maria Hatton (1853-1927) in Brooklyn in 1881 and died on 1 December 1899 in Mokena, Illinois.21

From these, a flourishing family tree is revealed.22

It may be that Sir Ronayne of the Lakes survives in the family papers of Lynch’s descendants. Notwithstanding, the role of Robert Adolphus Lynch in recording the wonderful legends of Killarney cannot be underestimated.

The literary gems belonged to him. This, Croker acknowledged in the first printing of the book. Now, almost 180 years since a Castleisland correspondent recorded the death of Mr Lynch, the O’Donohoe archive, Castleisland, underscores the valuable contribution of Robert Adolphus Lynch to the literature of Kerry.23

________

1 IE MOD/C31. The reporter added that Lynch was ‘distinguished for poetical abilities of no common order’ and that the specimens of his work in the book did not give an adequate idea of his higher attainments. The obituary, copied from the Kerry Examiner, concluded: ‘We have been told a production of such a character and equal to the expectation his acquaintances formed of him remains among his papers as well as a prose composition embracing or founded on the history of one of those strange and solitary men who took their romantic dwelling among the ruins and islands of Lough Lane. We would wish to see the remains of his intellectual labours to the public for among the many natives or residents of this country, who have earned so deserved reputation in the republic of letters, he was entitled to no humble rank. Another has however obtained a portion of the celebrity which was his due alone and the name of Crofton Croker is more generally heard in connection with the volumes to which he has no other right than that given by the prestige belonging to his editorial reputation. Lieut Lynch entered the army at an early age and retiring after the peace on half pay, settled in Killarney where a young and interesting family remain to lament his irreparable loss.’ 2 Lynch also supplied material to Croker for The Christmas Box (1829). 3 Fairy Legends was issued in 1825. Croker lost his manuscript for this book and his friends, who included Lynch’s cousin, Joseph Humphreys (1788-1859) of Hermitage, Kilmacow, near Waterford, first headmaster of the Claremont Institution (National Deaf and Dumb Institution), Glasnevin and contributor to the Amulet; Thomas Keightley (1789-1872); William Maginn (1793-1842); Samuel Carter Hall (1800-1889); Charles Robert Phipps Dodd (1793-1855) and Chief Baron David Richard Pigot (1797-1873), contributed to its production. A note in The Collected Works of W B Yeats (1989) vol VI, edited by William H O’Donnell adds Robert Adolphus Lynch to this list. In his article, ‘The First Group of British Folklorists’, The Journal of American Folklore, vol 68, No 267 (1955), author Richard M Dorson suggested that Croker’s treatment of Lynch’s literature was wanting: ‘The artificial gaiety of the narrative and the secondhand nature of its contents impair its value’. 4 Sometimes Garden Cottage, Killarney. It is not known where Garden Lodge/Cottage was situate but in one of his letters to Croker, in which he writes about a letter he is to deliver to the blind piper, Gandsey, Lynch states that ‘Lord Headley was near him’. Lord Headley’s mansion was Aghadoe House. See note above regarding Joseph Humphreys. At the end of June 1859, Henry T Humphreys Esq auctioned farm stock and a quantity of household furniture at Hermitage, Kilmacow. Mr Sainthill may have been Richard Sainthill (1787-1869), FSA. 5 In one of his letters to Croker at this time, he writes of plans to go to London to study law. 6 A number of exchanges between Lynch and Croker are referenced in Thomas Crofton Croker Correspondence in Public Library Cork An Index and Calendar compiled by Sheila M Kennedy held in Cork City Archives. They appear in volumes II, III and IV, all available online. The relationship between Lynch and Croker is unclear. It has been stated they were schoolfellows but their correspondence does not lend to such familiar acquaintance. 7 Lynch remained hopeful of publishing Sir Ronayne of the Lakes and composed a letter to Sir Walter Scott – to whom he hoped to dedicate the story – asking for his help in publishing it. Croker did not forward the manuscript to Sir Walter Scott for the cover letter remains in his papers. It may be that Croker had returned the manuscript to Lynch in the meantime, as suggested in the obituary to Lynch in note 1: ‘Among his papers … a prose composition embracing or founded on the history of one of those strange and solitary men who took their romantic dwelling among the ruins and islands of Lough Lane.’ See note on Philip Ronayne in The Legend of Lord Brandon (2014), p22. 8 Lynch suggested Croker add the preface and notes and also suggested the volume be entitled Feudal and Local Legends from the Kingdom of Kerry, ‘or any other title you please … we can divide the profits’. 9 In this he was inspired by Dunbar’s Wynter Meditation, ‘the sentiments were as congenial to my own frame of mind that I enlarged on it’. 10 Evidently Croker was thinking of a third volume though Lynch advised it would require material from outside Killarney which would detract from the whole. 11 The book was reproduced in one volume, Killarney Legends; Arranged as a Guide to the Lakes (1831). 12 He added, ‘It appears to me that many things might be altered with advantage and in consequence of improvements here, a few things might be added. If the work should go into another edition and I should be consulted, I would recommend those alterations and additions and also that it should be in one volume with an appendix which would render it a convenient handbook to the lakes’. He also mentioned that the change of publisher had cost him dearly as he had been promised £50 for a reprint and also alluded to the copyright of one of his poems (which had been broken up for the legends) explaining that the poem was of no use to him without it. In this he may have been referring to his Sir Ronayne of the Lakes. 13 He planned to leave his family at home to draw his half pay during his absence. 14 Quoting from Juvenal and Aesop, a play translated by Sir John Vanbrugh, he wrote to Croker, ‘The ministry have resigned and so have I: there’s nothing like following a good example; and I’m sure you would not have me be so base, as to retain office, when my party went out:- the truth is, that I have given up the Portmastership of Skibbereen. I confess that I was a little too hasty in my acceptance, before being acquainted with all the circumstances connected with the office; for tho’ prepared for a trifling salary, I did not expect that the situation would turn out the very reverse of the one desired by the above-mentioned honest Roger [Aesop]; that is, besides ‘bringing in very little’ that it would ‘cost a great deal’. 15 He also asked for the loan of £5. 16 He drafted the letter of recommendation himself and asked Croker to state he had known him since the time he served in the 2nd King’s German Legion. 17 See note 20. Robert Adolphus Lynch settled in Killarney in the early nineteenth century. It is not known where he was born. His father also wrote poetry, for some of the material sent to Croker was drawn from his father’s papers, and may have been published before. He mentions in one of his letters that Sir Richard Philips was his father’s bookseller. 18 Johanna had three elder brothers, John, Edmond and Batt and a sister, Ellen. The spelling of the name of descendant, Richard Allman Lynch, suggests alternatives to that given. 19 The daughters were Phoebe, born in Killarney in 1823, married, in Killarney in 1839, Robert Mathews; Mary, born in Killarney in 1826 married, in Killarney in 1846, John Daniel O’Connell; Ellen, born c1831, married James Hanifen c1851 (he died 1866). Ellen Hanifen had four children (Annie married Whalen; Edmond married Allen; Jeremiah and Phoebe). 20 Robert and Anna had issue Richard (1857-1901); Mary born 1862; Annie born 1863, and Phoebe Catherine, born in 1868. Phoebe Catherine Lynch married shoe manufacturer and businessman, Frank Elwin Brickett (1865-1915), a descendant of Hannah Dustin, in Haverhill in 1887 and had issue Iva Mae, born in 1888, who married Walter S Bailey. Walter and Iva had issue Dudley John Bailey, Thelma Elizabeth Germain, Valeska Brickett Bailey and one other, all born in Haverhill. The American Biography A New Cyclopedia (1919) vol VI, states that ‘Mrs Brickett is a descendant of Thomas Lynch, Jr, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence’. 21 Edmund had issue Robert Adolphus Lynch (1883-1943) who married in 1910 Marcia Ada Mitchell (Robert had two daughters, Mary Jane, born in 1911 and Roberta Mae born in 1913. Both were teachers in Moline. Mary married Daniel David Ziegler in 1945 and had a son, David Robert Ziegler, born in 1950); Henry Hatton Lynch of Blue Island (married with one son); Richard Allman Lynch (1886-1953) of Ottawa (married Ellison Graham Rennie in 1911 and had issue Edmund David Lynch (1914-2008), Richard Allman Ferris Lynch (1918-2005) and one other son); Phoebe Lynch (1889-1982) who married George Barnes of Joliet, Illinois in 1914 (and had one son). 22 Special thanks to Marie Huxtable Wilson, Tralee, for genealogical research of the Lynch family. 23 Croker wrote that Lynch had full power to claim as his and his alone, all the unacknowledged rhymes which appear in the volumes, regardless of whose name was appended to the book. See Legends of the Lakes, vol II, p233.