Finally they’d have to learn that this was a form of communism – where each of us was a servant of the boat

In the summer of 1938, one year before England declared war on Germany, 27-year-old Vere Chamberlain Harvey-Brain, author of Seychelles Saga and My Seychelles Years, set out from the south east coast of England for the Seychelles in a small converted fishing boat.[1]

With the aid of a small inheritance which enabled him to buy the boat, and two inspirational books, Yachting on a Small Income and Coconuts and Creoles, he was heeding ‘the imperious call of the sea.[2]

It had been dreams of sailing to New Zealand that had long fired the young man’s imagination. Indeed, My Seychelles Years describes his ambition thus:

V C Harvey-Brain’s boating career could be said to have begun when he was a small boy. One day he tacked a couple of old oilskins around an orange crate and then launched it on a weed-infested pond.

But the Seychelles had now captured his attention to the point of obsession. He told his mother of his plans to sail there and she was horrified, but ‘the Seychelles was on; I would put New Zealand into cold storage for the time being.’

His boat Viking was renamed Brian Boru:

Brian Boru was stoutly built of good old English oak. In hull form she was what is known as ‘cod and mackerel tail.’ A converted Brightlingsea smack she had a short flat counter stern and a bowsprit of modest length. She was 34 ft overall, 11 ½ ft beam, with a draught of 5 ft … fitted with an old Morris Commercial converted car engine.[3]

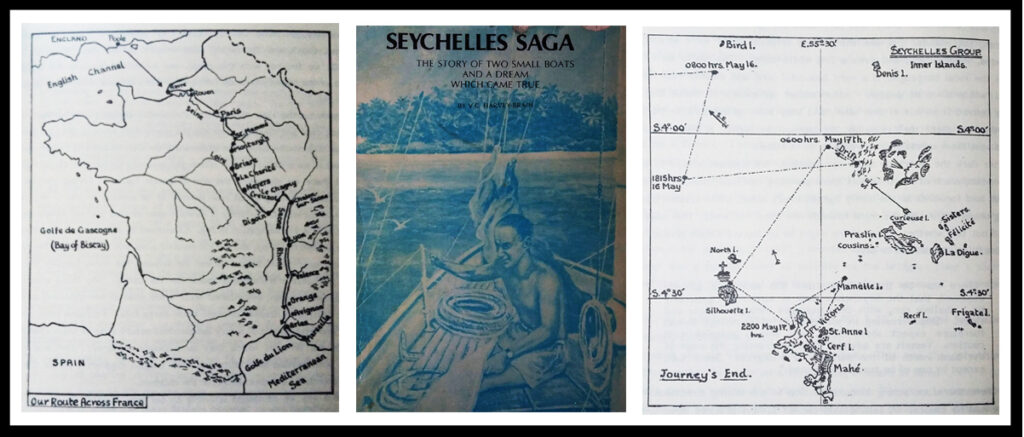

Vere set sail and by the time the winter months approached, he and crewmate Brian O’Hara had crossed the English Channel to France to navigate the inland rivers and waterways. Travelling along the Seine, they reached Paris, leaving there on 7 November 1938.

From the outset and for most of the duration of the voyage, one which would turn into almost a decade of adventure, finance would constantly be a problem. In fact they ran out of money very soon into their journey in France some fifty miles from Briare. They survived largely on the hospitality and generosity of those they met along the way, and by reaching various pre-arranged destinations to collect letters and much needed funds.

In France, Vere met Monette, ‘a ray of sunshine shining through the sombre clouds of a rather lonely life.’ Soon after, Brian Boru was frozen in at Chalon-sur-Saône, and it was there they were first approached by local reporters, intrigued by their ambitious endeavour. They were invited to lecture in the local town hall:

Alain Gerbault’s two understudies spoke, turn by turn, one in French and the other in English, about their boisterous crossing of ‘La Manche’ (the English Channel) as well as about their sojourn in France … In their cutter yacht, fitted with a 12 HP petrol engine for the canals, they finally intend to sail to the Seychelles … ‘We had expected to cross France in about 6 weeks,’ said Mr Brain, ‘here we are still after over 13 weeks.’[4]

Vere took advantage of their unexpected detainment and on a very cold winter’s morning in January 1939, he hired a bicycle to visit Monette, a two day cycle to Briare on unknown roads. After an all-too-short stay, theirs was a fond farewell tinged with melancholy, one which reminded Vere of his boyhood in Ireland:

A lonely soul had just passed through fleeting moments of almost unbelievable bliss … now I seemed to sound the depths of despair … it used to happen far back in the old days in Southern Ireland, each time I took leave of a well-loved cousin, the companion of my childhood and adolescence.[5]

A thaw allowed Brian Boru to continue its journey and Marseille was reached in February 1939, with no small amount of hardship endured. Brian O’Hara thought better of going out to sea and packed his bags to return to England. As luck had it, however, three men, Henri Faure, Wilson and Davidson (and a black dog) found Vere and offered their services as crew.[6]

They departed Marseille on 25 March 1939, their mission to be out of the Mediterranean before September when war was predicted to break out. When war did break out on 1 September 1939, they were still along the northern coast of Crete. On one occasion during this period, Vere remarked, ‘The night was so peaceful it almost seemed to give the lie to the evil threat of war.’[7]

Naturally, they encountered many storms, including one at Eliphonisi Bay. They were ‘pygmy playthings in the grasp of giants’ wrote Vere, ‘who petrified, clung on like limpets.’[8] Running in heavy seas near Cape Sicie, a shore battery was firing at a target out at sea and the canine on board became distressed and ‘almost mad with fear’:

Upon rounding Cape Capet we began to run into a bumpy sea and a saucepan of hot soup was flung off the stove splattering part of its content on the unfortunate animal’s back. The poor dog now in great distress began to whimper pitifully … the moral is that dogs really have no place on board a small yacht.[9]

Vere earned money by writing. At Cannes, he encountered a man who seemed interested in Brian Boru and on learning about the boat’s Morris engine, introduced himself as the publicity manager of Morris Motors, Cowley. Vere was invited to write an article about his voyage for the company magazine.[10]

Indeed, Vere’s interest in literature becomes apparent in his discourse on the history and legends of the countless places he encounters, such as Chateau D’If, where Edmond Dantès was incarcerated on the eve of his wedding to Mercedes; Calvi, where Lord Nelson lost his eye and the Levezzi Islands Sémillante disaster, ‘all of which is recounted in Alphonse Daudet’s L’Agonie de la Sémillante.’[11]

Meanwhile, a suspicious attitude was developing towards them on sea and land, ‘the atmosphere was heavily charged with war clouds.’ Indeed, en route to Malta, they put in – with great reluctance – at the Sardinian port of Tortoli: Italian territory, ‘and with the anti-British fulminations of Benito Mussolini we feared that the natives were bound to be hostile.’

However, their fears proved otherwise, and they were well received:

Just before sunset, we noticed a sail far away and fine on the port bow … it swept past to leeward with every stitch of canvas set and with ‘a great bone in her teeth’ – a glorious spectacle with swelling sails all stained a glowing red by the last rays of the lowering sun. We were soon to encounter many of these beautiful sailing vessels all along the south coast of Sicily. It was as though we had suddenly been transported into a bygone age – a romantic world that had almost passed away.[12]

Their journey to Malta continued, and one evening, as ‘onwards through the moonless night we drifted, onwards towards the loom of the searchlights and the sudden searing flashes from guns.’ Vere remarked they were ‘all ominous reminders of the troubled land and of the fragile peace’:

It was a dose of reality. I could not help but ask myself – would we ever reach the Seychelles before someone fired those guns in earnest?[13]

A local newspaper published an article, ‘Through France in a Yacht’ following which, in Malta, a number of curious people called to see them. Jim Moore, a 76 year old Canadian who was riding around the world on his bicycle, also made their acquaintance. He asked to join them and after a short stay to overhaul the boat, they continued towards the southern end of the Red Sea in mid July – with Jim and his bike on board.

They left Crete on 1 September 1939 for Egypt. In Alexandria, with war now certain, they were plagued by officials. It was expected there however that the war would not last six months. In Alexandria Vere lost Wilson, who was offered a job on a ship bound for Europe.

A New Challenge

Now Vere faced his own dilemma. His mother was in England, and war had been declared. Could he proceed with his journey under these circumstances. He approached the navy, and at Port Tewfik, a naval officer offered to put him ‘in cold storage’ as Examination Officer. After considerable thought, he returned to Navy House and accepted the job on board the Examination Vessel. Jim Moore packed his rucksack, unloaded his bike, headed to Port Said and from there to Crete, ‘his new-found love,’ where at Suda Bay, he was interned for the duration of the war.

In November 1939, Vere joined the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Stag in Suez Bay. Duties were light, conditions and pay good, and in comparison, made life on board Brian Boru seem like hard labour:

Each morning, if any ships were in sight to the south, it was our business to heave-up and to proceed towards them with the International Code Flag ‘K’ flying. This flag required a vessel to heave-to immediately.[14]

During watch periods, Vere read Seven Pillars of Wisdom – most apt with the Sinai desert just across the way. During free periods, he still ministered to the interests of Brian Boru, even spending the occasional night or two on board. During one of these visits to the yacht basin, he met a French girl sketching his boat, and it was the start of an enduring friendship, and a little good fortune.

The war, as Hitler overran Norway, Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands, was now in earnest. The French girl’s father, a canal pilot with the Suez Canal Company, volunteered with the Free French under the Cross of Lorraine. He also had a commission in the British Navy of Commander RNR and an appointment of captain of a 14,000 ton Free French armed transport. This led to a job for Vere as Liaison and Signal Officer. Indeed, Vere’s experiences during the war, including letters home to his mother, are given in two chapters of his book, Seychelles Saga.[15]

During the final years of the war, with great sadness and some regret, Vere sold Brian Boru in favour of Golden Bells, a boat he found in Cyprus designed by Norman Hart of Poole, Dorset.

The war over, Vere resumed his voyage to the Seychelles on 23 October 1946 with one companion, Major Dick Flatt from the Sappers. In a storm at Port Sudan, they came as close to death as it is possible to imagine.[16]

Major Flatt subsequently disembarked for Kenya, and four infantry men, after reading an article about the voyage in The Sudan Star of February 1947, offered their services as crew. At Aden, they lost one crew member due to incessant sea sickness but the remaining three, Ben, Fifie and Chai, held out. They left Aden in April 1947 and finally, or more to the point, incredibly, reached the Seychelles unscathed.

The port officer met them, and asked Vere, ‘How long do you intend to Stay?’ ‘With your permission,’ he replied, ‘For ever, and a day.’

Island Paradise

Ideals are like stars, you will not succeed in touching them – Carl Schurz

Many years later, Vere wrote:

Sooner or later, it is our lot to discover the hard fact that no Paradise exists on this Earth. But the struggle, the anticipation, the dreams, the effort to reach the impossible ‘Nirvana’ makes it all so worthwhile.

Vere’s career in the Seychelles was sketched by Athol Thomas in Seychelles Saga who explained that Vere’s arrival at Victoria, on Mahé Island, was to have been a port of call. However, Vere succumbed to its beauty:

He decided to stay – without any idea of how long. He went to Bombay and bought a war disposals ex-Admiralty Motor Fishing Vessel. He called it Marsouin (Porpoise) and set out to catch and salt fish and market shark-liver oil. The enterprise was not successful.

Vere subsequently shipped cloves from Pemba to Zanzibar, picked up coconuts from the abandoned Chagos Islands, took officials of the WHO to outlying islands, chartered Marsouin to scientists visiting the Amirantes during the International Geophysical Year, hunted for the elusive green snail shell with author William Travis, transported seabirds’ eggs, and guided film crews about the Indian Ocean. He also became a planter on Mahé, growing coconuts, patchouli and cinnamon. He was a pioneer tea planter.[17]

Indeed, the multi-talented Vere was also an amateur radio operator and was in demand in Victoria as an electronics expert and a diesel mechanic:

He became the British colony’s Jack Tar-of-all-trades. He did his best to help the backward colony prosper, and was a trenchant critic of politics that seemed to be taking it in the wrong direction. He had come a long way from a job with a jeweller in Holborn.

After twenty-eight years in Mahé, Vere resumed his travels to New Zealand. All did not go quite to plan however, and his journey was completed by air. ‘His final landfall … was Perth.’[18]

The following reveals that at some stage he was joined by his mother:

Mrs Harvey-Brain, a former resident of the Seychelles Islands, lived in Hobart for some time. Her son’s plantation, because of the increased price of copra, has been doing a flourishing trade.[19]

Vere did marry, but not to one of the women he met during his travels:

I did not marry either of the charming young French girls I’d met along the way. I suppose I was far too much in love with small ships and the sea to have much time to spare for the arms of women. One ambition I did attain in full measure. I became the sun-bronzed sailor of my youthful dreams and I enjoyed the freedom of the sun-drenched tropical seas for over 28 years.[20]

For those who wish to pick up on the story from here in more detail, My Seychelles Years, published in 1987, is the next chapter in his life. On its publication, Vere’s address was Surfdale, Waiheke Island, New Zealand.

He died on 30 September 1997 aged 86 and was buried at Waiheke Lawn Cemetery, Auckland, where his headstone is inscribed:

A gentleman, author, master mariner & friend.

He stood for what was right.

Rough seas are past, the captain is at rest.[21]

Kerry Roots

Vere Chamberlain Harvey-Brain seems to have regarded himself as an Irishman. During a conversation with a navigation officer during the Second World War, it was remarked that ‘You English are for us quite incomprehensible.’ Vere replied, ‘Irish you mean … there is a difference you know.’[22]

Indeed, his maternal roots were wholly Irish.

He was, however, born in Huntingdonshire on 8 July 1911, son of journalist Joseph Harvey Brain of Buckhurst Hill, Essex and Manor House, St Ives, Huntingdonshire and Evelyn May Leslie McCarthy.[23]

Joseph and Evelyn married in St Peter’s Church, Aungier Street, Dublin in March 1910. The ceremony was performed by Rev John Herbert Leslie, uncle of the bride. Evelyn’s father, Richard Hillgrove McCarthy (1841-1908), JP of Glebe House, Woodford, Listowel, Co Kerry, had died a few years before, and she was given away by her brother, Dr William Hillgrove McCarthy.

Through her mother, Jane Leslie, Evelyn was a niece of the Church of Ireland historian, Canon James Blennerhassett Leslie of Clouncannon, Faha, Co Kerry.[24]

Vere paid a lasting tribute to his mother, and by extension, his Kerry roots, in Seychelles Saga:

In memory of my mother

Who encouraged me

And made all these things possible.

___________________

[1] Seychelles Saga: the story of two small boats and a dream which came true was published in 1982; My Seychelles Years was published in 1987. ‘With the whine of a high-velocity shell, a 2cwt piece of metal shot 500 yards over Portsmouth Harbour last night, when a turbo-alternator exploded at £350,000 premises of the Portsmouth Electricity Committee opened a month ago. It landed on the beach, narrowly missing several houses and yachts – passing within two feet of a sailing cutter, the Viking, belonging to Mr Harvey-Brain of London and Mr L O’Hare, who leave on a world trip today’ (Daily Mirror, 26 August 1938). ‘On the night of August 25 the yacht, which was then known as the Viking, was in the Camber Dock, Portsmouth, and narrowly escaped destruction when part of a flywheel at the Portsmouth Power Station nearby became detached in an explosion … Next day the owner of the yacht, Mr Vere Chamberlain Harvey-Brain, of Uxbridge Road, Kingston-on-Thames, told the Hampshire Telegraph and Post that the yacht’s name was Brian Boru. It was stated that Mr Harvey-Brain, with a Mr B O’Hare, contemplated a voyage to Seychelles in the Indian Ocean.’ Mrs Harvey-Brain told reporters that her son and several others were going to sail the yacht to an island in the Pacific where ‘they hope to settle down. Later I am going to join them’ (‘Mystery Yacht Missing,’ Gosport Journal, Hampshire Telegraph and Post and Naval Chronicle, 9 September 1938). See also ‘Plans to Buy 6s a Week Paradise’ (The Daily Mirror, 8 September 1938). [2] Vere spotted Yachting on a Small Income (1925) by Maurice Walter Griffiths (1902-1997) in a shop window in London. Until then, Vere had regarded yachting as an exclusive pastime. Coconuts and Creoles, which Vere’s mother came across in Kingston-upon-Thames public library, was written by a former Archdeacon of the Seychelles. The cleric was located and invited to London to meet the Harvey-Brains and discuss his experiences of the islands. Coconuts and Creoles (1936) was the work of J A F Ozanne. James Alured Faunce Ozanne (1881-1957) was a former Roman Catholic priest of St Patrick, Nottingham who was received into the Church of England. In 1920, Rev Ozanne was rector of St Peter’s (St Pierre du Bois), Guernsey when presented with three war medals by Major-General Sir John Capper, Lieut Governor of Guernsey, for his service as captain in the Royal Garrison Artillery, winning the 1914-15 Star, the General Service Medal, and the Victory Medal. In 1931, Rev Ozanne rose to eminence as Archdeacon of Seychelles. In 1936, he was Vicar of Bassingbourn, Royston, Herts. In 1954, his residence was East Hanningfield, Essex. The following is of interest: ‘Mrs James Ozanne, a lady of 82, is one of the passengers on board the Carnarvon Castle, which is sailing for South Africa tomorrow. The octogenarian is going to Seychelles with her son, the Rev J A F Ozanne, who has been recently appointed Archdeacon of Seychelles. Mrs Ozanne, who is the widow of James William Ozanne, one time chief correspondent in Paris of the Daily Telegraph, is looking forward to the sea voyage. It is not her first experience of the tropics, for she spent part of her childhood in St Helena, where her father, Colonel Faunce, was officer commanding the troops’ (Nottingham Evening Post, 22 October 1931). The ‘octogenarian’ was Constance Emily Faunce (1849-1946). James Alured Faunce Ozanne married Jemima Patricia Ryan (1877-1947) of Clonloghan, Ennis, Co Clare, daughter of Michael William Ryan and Margaret O’Halloran, in Paddington, London on 27 January 1915. Rev Ozanne was a nephew of Robert John Thorpe Ozanne (1862-1946), master of Bedford School, Guernsey for thirty-eight years. R J T Ozanne was also editor of The Ousel, and father of Robert de la Condamine Ozanne (1899-1986), Deputy Inspector General of the Indian Police, and Squadron-Leader John Gabriel Ozanne (1907-1992), RAF, Licence ès Lettres (BA) University of Strasburg. It is probably also worth noting that Rev Ernest Albert Newton, Archdeacon of Seychelles 1912-1917 appears to be the author of In Double Harness Dialogues on Religion (1897). [3] Seychelles Saga The Story of Two Small Boats and a Dream which came True (1982) by V C Harvey-Brain, pp4-5 and 29. ‘Brian Boru: The Irish warrior king of Munster who spent his youth fighting the Danes who were invading his country (926-1014).’ His fellow navigators were Brian O’Hara and Fluff the cat, a stray they took on board. [4] The article was published in Le Progrès, 28 December 1938 and in Seychelles Saga (p32). [5] Seychelles Saga, pp 36-37. [6] Davidson and the dog would disappear soon after to be replaced by Basset Digby, who departed at Bonifacio, as did Henri Faure, after a close encounter with a storm at the Cliffs there. ‘I screamed to Willis as I dashed down below. There, by great fortune, the faithful engine started at the first swing. Had it not done so this story would never have been told.’ [7] Seychelles Saga, p86. [8] Seychelles Saga, p79. [9] Seychelles Saga, p54. [10] Seychelles Saga, p55. [11] Seychelles Saga, p62. [12] Seychelles Saga, p66. [13] Seychelles Saga, p67. [14] Seychelles Saga, p96. [15] Pages 101-121. See also My Seychelles Years (1987). [16] ‘Shipwreck,’ pp127-133. [17] A series of 1960s articles, ‘My Desert Island Journal,’ by Macdonald Hastings, who was sailing to the Amirantes, revealed that Harvey-Brain was guide: ‘I’m sailing in a storm-battered schooner called the Marsouin (The Porpoise) with an English skipper, Captain Harvey Brain, a crew of Creoles and a Chinese photographer to take pictures of me landing on the island. I’m lucky to be sailing with Brain. He is an ex-naval officer – sun-locked, grey-eyed and balding – who has been bashing round the treacherous reefs of these coral islands ever since the war’ (The People, 7 August 1960). [18] Seychelles Saga, pVII. The book was published by V C Harvey-Brain, Riverton, W.A. 6155, printed by Rank Xerox Copicenter, 5 Barrack Street, Perth, W.A. Vere self-published the book after having difficulties finding a publisher. He took a course in printing and publishing in Mt Lawley College of Advanced Education. Reference, ‘Patience also the hallmark of this writer-yachtsman,’ review of Seychelles Saga, held in Castleisland District Heritage, reference IE CDH 25. The review is by journalist and author, Athol Thomas, who also wrote the introduction to Seychelles Saga. He met Harvey-Brain when he went to the Seychelles in 1965 to write a book – evidently Forgotten Eden: a View of the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean (1969). A tribute to Athol Thomas (1924-2012) can be read at this link: http://watvhistory.com/2012/11/tribute-to-athol-thomas-1924-2012/. [19] The Mercury (Hobart), 16 June 1953. Tasmanian Government Immigration papers give the address of Mrs Evelyn Harvey-Brain in 1941 as ‘Les Palmes,’ Mount Fleure, Port Victoria, Mahé, Seychelles Islands, Indian Ocean. [20] His wife was Seychelles native, Hermence Augusta Calais, daughter of Cerf Henry Calais and Neemie Clemence Elisa Dyer. [21] Reference: find a grave, Block 8, Lot No 14, Memorial ID 165157382. Sincere thanks extended to Marie H Wilson for genealogical research. The following was posted on hamgallery.com, a radio operators site: VQ9HB/D 1966 Desroches Island/Operator: Vere Chamberlain Harvey-Brain./Silent Key: Sept 30 1997./Headstone inscription:/A gentleman, author, master mariner & friend./He stood for what was right./Rough seas are past, the captain is at rest./QSL courtesy of G4UZN/Info courtesy of W5KNE. [22] Seychelles Saga, p103. [23] In 1912, Joseph Harvey Brain of St Ives, Huntingdonshire, was adopted as prospective Unionist candidate for Norwich. Joseph Harvey Brain died at 12 Springfield Road, , Berkshire on 25 October 1923, and was buried at Buckhurst Hill on 30 October1923. The date of demise of Mrs Evelyn Harvey-Brain, who joined her son overseas, has not yet been ascertained. [24] Further reference to the McCarthy family of Listowel and the Leslie family of Clouncannon on Castleisland District Heritage website; see ‘James Blennerhassett Leslie, Ecclesiastic and Historian.’