Murder at Dromulton, a study of the circumstances surrounding the tragic case of Thomas Browne of Dromultan, Co Kerry, shot dead in 1882 during agrarian unrest, and the subsequent executions of Sylvester Poff of Mountnicholas and James Barrett of Dromultan for the crime, is the work of the late Peter O’Sullivan of Dublin.[1]

O’Sullivan’s research placed the murder and its sequel in its context, the Land War, in both the Castleisland district and the country as a whole. The work was divided into three chapters: an investigation into the causes of the Land War, a summary of the Browne, Poff and Barrett case in this context, and reaction to the convictions by those on opposing sides.

O’Sullivan tackled the subject of high rents in the late 1870s in his opening chapter. He observed that ‘possibly the greatest cause of resentment was the custom of raising rents where the tenant had carried out improvements on his holding.’ He cited the study of Barbara Lewis Solow, ‘In the Southwest, rents were raised frequently and steeply, right through the 1870s. Kerry stands apart from the rest of Ireland in this respect and conditions prevailed in Kerry that had not been known for decades elsewhere.’

A series of adverse weather conditions affected all aspects of farming in the late 1870s which combined with a slump in butter prices. This added to the existing resentment towards landlords and helped to create ‘an agrarian crisis of major proportions.’ O’Sullivan examined the statistics:

By the end of 1879 the tenant farmers in the area were facing financial ruin. The banks and shopkeepers panicked, refused to grant credit, and called in their loans. High rent levels were now looked on with renewed hostility. The number of evictions in Kerry leaped from 15 in 1875 to 182 in 1880. The tenants were not prepared to accept their fate passively as their forefathers had done during the Great Famine. They were prepared to act to defend the improvements in living standards that they and their families had come to regard as necessities.

Reports of public order offences spiralled from three in January 1880, to 208 in December 1880. Reports of agrarian violence leaped from 14 in 1879 to 245 in 1880 and 455 in 1881. The objects of attack were landlords, agents, police, bailiffs, process-servers.

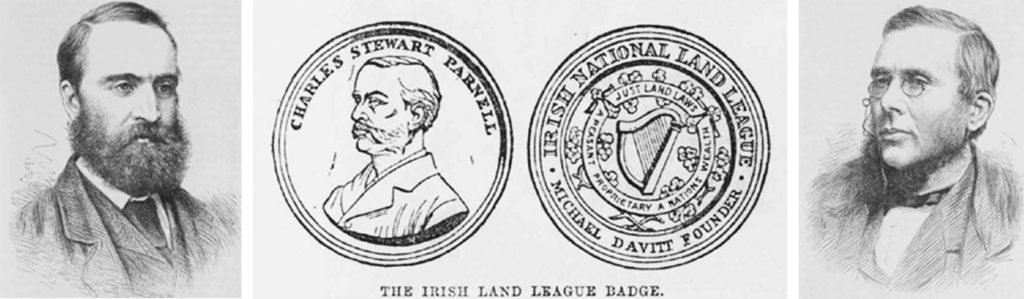

Timothy and Edward Harrington, founders of the Kerry Sentinel, emerged at this time as leaders of agrarian agitation in the county (the former becoming the founder and president of the Tralee branch of the Land League in Kerry). Their work contrasted with the conduct of land agents Arthur Edward Herbert and Samuel Murray Hussey – ‘hate figures’ – for example, the latter’s purchase of the Harenc Estate for £80,000 to the disdain of the tenants who hoped to purchase.

Hold the Harvest

In 1880, the league’s catch-cry was Hold the Harvest, urging its members to pay no rent beyond Griffith’s Valuation and to prioritise the needs of family, and debts to shop-keepers, over rent. The magnitude of the situation was shown in a meeting of the Land League in the village of Currow in September 1881 attended by 7,000 people.[2]

Statistically, there was more violent crime in Castleisland than in the rest of Kerry put together. Arrests heightened the tension in the community and Forster’s ‘village tyrants’ became local heroes. ‘Rarely before can any part of Ireland have witnessed such an outburst of rage against the established order.’[3]

Targets now were not only landlords, agents, process-servers and bailiffs, but anyone in the community who co-operated with such people in any way.[4]

O’Sullivan described how the Land War was fought at two levels: the open legitimate agitation of the Land League and the underground action of secret societies, generally known as Moonlighters in the south and south west of the country. They were regarded by the community with a mixture of pride and fear.[5] Generally, however, they had widespread sympathy amongst the people because it helped them ‘withstand the landlord.’[6]

Unfortunate Timing

O’Sullivan observed, in his second chapter, how Thomas Browne became a landlord to his neighbours, the Fitzgerald family, at a time ‘when the entire community was practically in a state of war against landlords.’[7]

In the lead up to Browne’s murder, a stone was thrown at him by Patrick Fitzgerald, John Dunleavy and Jeffrey Fleming. In the wake of his murder, a neighbour, Bridget Brosnahan (or Brosnan), became main witness for the prosecution. O’Sullivan, in discussing the idea that the intended crime was known in the community, stated, ‘Bridget Brosnahan, the chief witness, must have known. The sight of two men crossing over a ditch into Browne’s field was enough to send her running in panic to warn Mrs Browne.’[8]

O’Sullivan addressed the question of why nobody in the community informed the police about the threat against Browne, and reasoned, ‘To notify the police would be tantamount to treason in a community in a virtual state of war with the tenants on one side, and the landlords, supported by the forces of law and order, on the other.’

Thomas Browne, though he had farmed the land for 16 years, was regarded as a ‘blow in.’ He had come in on land that had been occupied for generations by the Fitzgeralds. Worse than that, he had lately become their landlord:

The Fitzgeralds did what was necessary to defend their land, and according to unwritten law in Kerry, when men had to defend their land, any action was justifiable. [9]

O’Sullivan retraced the movements of Poff and Barrett on the day of the murder, their walk to the post office to collect a letter, their card playing and drinking, their onward journey to check Poff’s cattle and to hunt rabbits, and described the picture formed as ‘a day in the life of an evicted farmer.’[10]

O’Sullivan summarised the two trials of Poff and Barrett in his third and concluding chapter (sub-titled ‘The Aftermath’), and the final judgment, with particular reference to John Dunleavy who ‘could clear the prisoners by telling the police what he knew but they (the Moonlighters) would shoot him if he did.’[11]

In noting Judge Barry’s summing up, O’Sullivan formed the opinion that ‘in a sense, a whole community was on trial for the murder of Browne’:

Poff seems, at this point, to realise that he was being condemned for the crimes of a community to which he didn’t belong. He interrupted the judge to say that he had told the police all he knew on two separate occasions. The judge responded by reading the statements of both prisoners, and again commented on the fact that they had failed to warn the Browne family.[12]

It mattered not that nobody had warned the Browne family, that nobody had informed the authorities – not even star witness, Bridget Brosnan. It was of no consequence that Poff, from a different parish, knew nothing about the Dunleavy, Browne or Fitzgerald families. There was no place for truth and justice at this particular moment in Irish history.

O’Sullivan sought the judgment of the community in its oral tradition:

The evidence of folklore is that, from the very beginning, the people in and around Dromulton never doubted the innocence of Poff and Barrett. Of all the older people on the area, who remember what their parents and grandparents had to say, I haven’t met with, or heard of one, who believes they were guilty.[13]

Conclusion

The verdict of guilty added another source of division to an already deeply divided society. Predictably, the tenants and supporters of the Land League were on the side of the condemned men. For many, the verdict of a Cork jury was another proof of what was regarded as a corrupt judicial system in Ireland. On the other side, supporters of the establishment hailed the verdict as a triumph for law and order in the battle against agrarian crime in Kerry.[14]

In his final assessment, O’Sullivan assigned the tragedy to land:

Hunger for land brought Thomas Browne to his death. It drove him to ‘buy in’ not just his own farm but the farms of his neighbours, the Fitzgeralds. By doing so he raised the threat of eviction, real or imagined, over the heads of the two families. As long as he lived, that threat would hang over them. The only lasting solution to their problem was that Browne should die, and the Moonlighters were asked to do the deed. The news that Browne was to be shot got abroad, and naturally, spread quickly through the community. But not a word reached the ears of the authorities. The neighbours understood the Fitzgeralds’ predicament. They themselves probably knew that fear of eviction. They turned their heads away while Browne was being murdered. The two murderers were confident that no one in the community would inform on them. They went into Browne’s field and shot him in broad daylight without making the slightest attempt at disguise.[15]

Indeed, O’Sullivan likened the case to that of Moore and Foley of Reamore whose differences over land John B Keane addressed in his play, The Field.

Moore and Foley of Reamore[16]

Beyond the brown hill of Reamore there’s pleasure calling me, When summer skies are dreaming o’er and winds are blowing free, Away across the turfy ridge is many a verdant lawn, Around by dear old Ivy Bridge and Mochacnucawn![17]

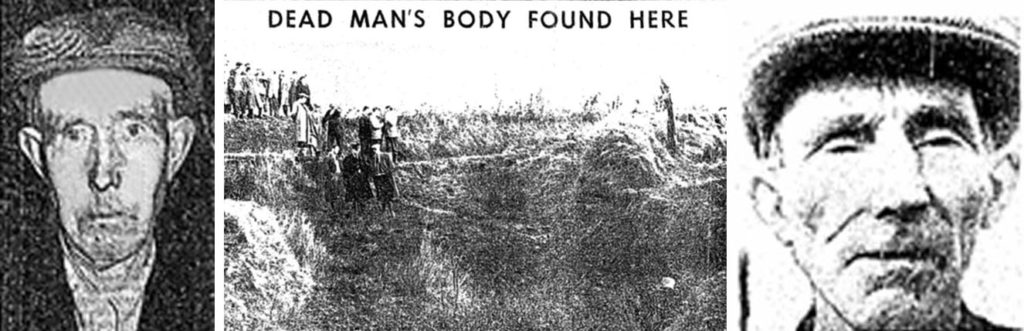

The body of 50-year-old unmarried farmer, Maurice (Moss) Moore was discovered by Gardaí on 15 November 1958, more than a week after he had been reported missing. His body was found concealed in a gulley at Reamore, Kilduff, about five miles from Tralee. He had been assaulted and strangled to death.

Moss Moore, a slightly built man of about 10-11 stone, 5’ 8½ in height, lived alone with two dogs for company, Smallie, a black and white collie, and Spring, a fawn greyhound. He kept about 12 acres, and a few cows and pigs.

Moss Moore had last been seen alive on the evening of Thursday 6 November 1958 when he parted company with his friend, Timothy Sugrue of Tylagh, Kilduff, at Reamore Cross at about 10.20pm. He had been playing a card game of 110 –– as was his social habit – with Timothy and others at the home of a neighbour, Mrs Julia Collins.[18] He was dressed in a dark jacket and trousers, brown overcoat, old brown cap and hobnailed boots, and carrying a black lamp and a stick.

In the weeks before his death, Moss Moore had expressed concerns to friends that he believed he was being shadowed.[19] For this reason he carried the lamp and stick for his three-quarter mile journey home to his three-roomed cottage. This was the last time Moss Moore was seen alive by friends.

On Saturday, he was missed (for the second day) at Kilduff Creamery and friends called to his home. They knew immediately he had not been there because the cows were un-milked and the animals unfed. The dogs, which he always kept locked inside when he went out, were running loose. Indeed, droppings on the floor inside the cottage suggested the dogs had been alone in the house for some time before being released by person or persons unknown.

Moss Moore’s disappearance was reported to the Gardai and a search of the district followed. The search went on, often in poor weather conditions, over a period of more than one week.

The subsequent discovery of Moss Moore’s cap, stick, and then his body, concealed by rushes in the narrow neck of the gulley near his home – an area which had been traversed many times by volunteers who joined in the search – was made by Sergeant Michael Costello, Tralee, and Chief Superintendent Pat Cronin.

The black lamp was found later using a mine detector operated by a soldier from Collins Barracks in Cork. It had been hidden in a cabbage and mangold plot 100 yards from where the body was found.

State pathologist Dr Maurice Hickey soon arrived with Murder Squad detectives from Dublin.[20] Three Gardaí lifted the body on to a stretcher and, to gasps of horror from the crowd present, it was taken away for post mortem and inquest.

Maurice Moore was buried on Tuesday 18 November 1958 at O’Brennan (O Braonain) Cemetery. It was reported to be the biggest funeral ever seen in the district.[21]

Three days before his murder, Moss Moore had telephoned Garda Paddy Kavanagh and informed him he was being tormented by his neighbour, Daniel Foley. He asked the officer to call to him about the matter but this was not followed up before his disappearance.[22]

Daniel (Dan) Foley, a farmer, lived in close proximity to Moss Moore. He was about 15 years older than him, an old IRA man, broad and strong in appearance but reserved and private in manner. He was married to Nora McMahon; they had no children. Foley’s invalid brother, Michael, lived with the couple.

Good neighbourly relations had existed between Moore and Foley but deteriorated in mid-1957 when a dispute arose between them about the placement of a boundary ditch they had agreed to rebuild. Neighbourly talk ceased and the matter was put in the hands of their solicitors.[23] Such was the state of affairs when Moss Moore was found murdered.

Dan Foley, because of the breakdown in relations with Moore, was regarded as prime suspect. He had motive and opportunity. Indeed, in the wake of the body being found, notices had been displayed on the gable of Kilduff creamery and at Reamore Cross, ‘Boycott Dan Foley the Murderer.’

His unproven guilt was further endorsed by a split lip which was noticed on him on Friday, the day before Moss Moore was reported missing.[24] Foley claimed the injury was ‘a puck from a cow.’ There was also the widely held belief that whoever hid the body of Moss Moore would have had great knowledge of the area.

Dan Foley was questioned on a number of occasions but Gardai had no evidence against him beyond circumstantial. There were no witnesses, there was then no DNA – indeed, there was no crime scene; a wake had been held in Moore’s cottage before detectives had cordoned it off. The Attorney General, Aindrias O Caoimh, concluded there was ‘insufficient evidence to prosecute’ and the crime remained unsolved.[25]

In the years that followed, the quality of Dan Foley’s life was severely compromised. He was ostracised by boycott, and, shortly before the first anniversary of Moore’s death, about 15 shots were fired into his kitchen narrowly missing the occupants.[26] This followed a deliberate explosion at his farm months earlier.[27]

Dan Foley collapsed and died in a field near his home on the evening of 17 May 1963 and he was buried in the new cemetery, Rath, Tralee. This raised eyebrows at the time because his ancestral burial place was O’Brennan Cemetery, where Moore had been laid to rest.

Nora Foley lived on in the house for fifteen years until her death on 19 February 1981. Both properties then stood unoccupied. Foley’s 25-acres of land with cottage was put up for sale soon after. Nothing now remains of the Foley residence and in 2010, only the gables of Moss Moore’s cottage survived.

Hunger for Land

O’Sullivan was astute in drawing parallels between the two cases: the murders of Browne and Moore occurred in rural districts in Kerry, both were believed to have been committed over land, both remain unsolved. However, here the parallels diverge a little and the differences that emerge illustrate the changes that had taken place in the 75 years or so that separated the two cases.

Moss Moore did not present Dan Foley with the threat of eviction; both had the security of their own land. Moss Moore was not murdered in broad daylight in front of his neighbours; he was set upon under cover of darkness when the killer or killers were assured there would be no witness. Moss Moore was not killed and left where he fell, but his body was taken and concealed in a ravine.

The last people to see Moss Moore alive were not compelled to flee the country for their own safety, in fear they would be treated with suspicion. No person came forward on the strength of a reward prepared to commit perjury.

No innocent person was rounded up, tried and convicted for the crime on pre-conceived ‘evidence.’ No petitions were signed and presented to the highest echelon of government to prevent further tragedy.

Moore and Foley’s dispute focussed on a boundary; it was a disagreement between two people who lived side by side. In this respect, it might be construed as more about the human condition than it was about land.

However, in order to determine if murder, or even conspiracy to murder, could have been committed over a boundary – for neighbours dispute about many things – the significance of the boundary must be understood, as well as the nature and depth of animosity that existed between the two men.[28]

Reamore, like so many districts in Kerry, had its share of land disturbances in the later part of the nineteenth century. In 1861, the area had been opened up by a new road from Tralee to Abbeyfeale that ran between Ballybeggan gate and Reamore Bog. Reamore, a large district, would now supply ‘inexhaustible turbary to the town of Tralee.’

The bog would bring its share of issues during the land agitation. There were incidents of malicious fire of turf there in the 1880s and in 1888, a horse belonging to a bog ranger for Lord Ventry, residing at Raemore, was found mutilated after the ranger let turbary to ‘an unpopular farmer.’

On 22 November 1888, the body of 45-year-old Denis Daly of Ballinknock, Carrignafeela, was found by a boy named Michael Moore on the road at Muingnaminnane. Daly had been shot in the head returning from Reamore Bog.[29]

The house of farmer Thomas Creany of Reamore was raided by police for arms in 1890 and a few years later, 70-year-old Patrick Geaney of Reamore was savagely beaten by Moonlighters on suspicion of being a ‘grabber.’[30]

The land issues at Raemore, a place often described as ‘near Castleisland’ rather than near Tralee, spilled into the twentieth century. John and Maurice Reidy of Reamore voiced grievances about their eviction in a letter to the press in 1908, and in 1930, the Moore and Geaney families took legal proceedings against each other over a right-of-way through Reamore Bog.[31]

An Emerging Republic

This backward glance at the district contrasts with the romantic ‘brown hill of Reamore’ and the quiet, safe, and social place described in the Moore murder reports of 1958. The crime against Moore occurred in an Ireland that had moved on considerably from the system endured by Poff and Barrett. But it occurred in a district, one of countless, that was still only slowly recovering from the persecution of the past.

In many respects, the system that failed to prosecute Dan Foley – in deep contrast to that which hanged Poff and Barrett – might be applauded if, as was stated, there was no hard evidence to convict him. At the very least, the mechanics of law appeared to work on the principle of innocent until proven guilty.

In the 1960s, John B Keane set to work on a new play. He went out to Reamore to meet Dan Foley but a meeting was declined.[32] Nonetheless, the gifted tragedian decided to tackle a subject that might well have followed him home on a dark night. In 1965, when The Field was staged at the Olympia, John B Keane was described as fearless, and The Field hailed as a play that ‘cried out to be written.’[33]

It cried out to be written in 1883, when Poff and Barrett were hanged for the murder of Thomas Browne, a man who almost certainly did not meet his death at their hands. Theirs was a tragedy of all proportions.

Society was ripe for John B Keane’s subtle treatment of people and land in The Field. Its impact catapulted him and his work to their worthy place in Irish literature. Into Keane’s field most certainly went Moore and Foley, but in the same place we also find Browne, Poff and Barrett – and a thousand others.

______________________

[1] Peter O’Sullivan, formerly of Farranfore, studied for an MA in Local History at the National University of Ireland. A copy of his study, Murder at Dromulton An Incident in the Land War in Kerry dated 1996, is held in the O’Donohoe Collection, reference: IE MOD/C73. [2] In 1881, 72 people from Kerry were arrested under the Peace and Protection Act, 15 of whom were from Castleisland. [3] p19. [4] Agrarian outrage in the county grew from 297 cases in 1880 to 401 in 1881. Violent attacks increased from 16 and 73 in 1880 to 35 and 96 in 1881. [5] The underground societies met on the first Sunday of every month, at different venues, notice of place not being given until a day or two before it took place. At these meetings the ‘captain’ gave orders about houses to be visited and punishment to be meted out. [6] p23. [7] p25. [8] p31. ‘A schoolboy who ran to tell Ellen Fitzgerald found her reaction to be that of ‘one who knew’.’ [9] p32. [10] ‘The letter so frequently mentioned in the course of the trial, for which Poff went to Scartaglen on the fatal day, was from his sisters, and had reference to his approaching intended emigration’ (Kerry Independent, 1 January 1883). [11] p45. [12] p45. [13] p48. [14] In pp62-64, O’Sullivan looked at the role of the defence in a section sub-titled, ‘A Flawed Defence’ and discussed the lack of character witnesses at the trial, notably by the clergy, who afterwards signed the declarations. It could be argued that Fr Scollard’s deep involvement in the case from the beginning may have dissuaded the clergy from going up against each other in public. See http://www.odonohoearchive.com/poff-and-barrett-the-role-of-father-scollard-in-their-conviction/ ‘Poff and Barrett: The role of Father Scollard in their conviction.’ [15] p71. [16] Reamore, sometimes Raemore, Reighmore, otherwise Rathmore (OSI map), lies in the parish of O’Brennan, which borders the parish of Ballymacelligott. [17] ‘Beyond the Hill’ by D M Brosnan, The Liberator Tralee, 3 April 1926. Beyond the brown hill of Reamore One lovely summer’s day I went to wander and explore In places far away; By Carrickcannon’s fields of green By Renagown and then Adown the boglands of Toorean To Glounanculha Glen! Beyond the brown hill of Reamore The heart of Ciarraedh’s hills – The magic of a wondrous love The passing ages fills; Wild Beauty weaves her mystic clue And pleasure’s calling me Where fields are green and skies are blue And winds are blowing free! [18] Jeremiah Collins and Mr and Mrs Timothy Curran were in the group. [19] ‘It is understood that the name of a person whom Moore said was shadowing him has been given to police’ (Kerryman, 6 December 1958). A friend of Moore’s informed a reporter that Moore knew he was being watched, and would not light his torch on his way home or switch on the electric light in the house, but would get around the house by means of lighting matches. About three boxes of spent matches were found in the house (Evening Echo, 17 November 1958). [20] In January 1959, it was reported that the Technical Bureau had shot an entire 35mm film of the locale, retracing the victim’s probable route home from Reamore Cross, for showing in Dublin. [21] ‘The coffin was borne into the cemetery by four nephews – John, Edward and Liam Moore and Michael Brosnan – followed by Laurence Moore, Knockeen, Castleisland; Michael Moore, Droum (brothers); Mrs Margaret Hanafin, Leith, Abbeydorney (sister) and nephews and nieces … The burial took place in the family plot in which are interred his father, mother, and their other five children’ (Irish Independent, 19 November 1958). [22] Death in Kerry: The Story behind The Field (2010) RTE Radio 1 documentary by Ciaran Cassidy and Peter Woods. [23] ‘On the application of Mr Donal E Browne, LLB, State Solicitor, for the plaintiff, Justice R D F Johnson, at Tralee District Court, adjourned for three months a civil bill brought by Maurice Moore, farmer (deceased), of Reamore, Kilduff, Tralee, against Daniel Foley, farmer, same address. The claim is for £50 damages for alleged trespass on lands, bogway and road situate at Reamore on diverse dates from the 29th July 1957 whereby as a result of the alleged wrongful trespass the land, bogway and roadway have been damaged to plaintiff’s loss in the sum claimed. Mr Gerald Baily, Solicitor, represented Foley’ (Irish Examiner, 7 March 1959). [24] Death in Kerry: The Story behind The Field (2010) RTE Radio 1 documentary by Ciaran Cassidy and Peter Woods. [25] ‘Many locally believed and still believe that Dan Foley was protected because of his IRA service … Foley’s former IRA colleague, Thomas McEllistrim (Snr) was local Fianna Fail TD and head of Kerry’s premier political dynasty. Fianna Fail had regained power in 1957. It remains a rumour unsubstantiated yet believed’ (Sunday Tribune, 23 September 1990). [26] The shots were fired on Wednesday evening 4 November 1959. A memorial was published in the Kerryman, 7 November 1959, by a friend of Moore: Your life was love and labour,/Your love for your neighbours true;/The sudden way you had to die I will always remember and wonder why,/Will those who think of him today,/A little prayer to Jesus say. [27] On 9 April, a charge of gelignite was detonated on Foley’s farm. The explosion, heard at 11.30pm, blew a hole in a fence and bank yards from an outhouse. Nobody was injured. [28] It is well to remember that in 1958, the perpetrator, Dan Foley or otherwise, did face the death penalty. [29] Laurence Hickey and Denis Connell, relatives of the dead man’s wife, were tried for the murder. Laurence Hickey was found guilty and hanged in Tralee prison on 7 August 1889. He left a written confession of his guilt, warning others of what he had suffered and not to commit crime. The jury could not agree on Denis Connell and he was subsequently tried on four occasions. The last we hear is in June 1890, that Denis Teahan of Muingnaminnane and his family had been ‘secretly removed’ to the train station under escort for Kingscourt, Dublin where other Crown witnesses from Kerry were residing. [30] Landlord John Conway Hurley of Waterbeach, Cambs took up residence at Glenduff House, his property in Kilduff, in the process of which he had evicted a man named Thomas O’Connor. A notice placed on Hurley’s entrance gate threatened death to anyone who bought hay from him. Geaney had defied the notice and this was supposed to have been the reason for the attack. [31] It appeared the Geaney family had tried to prevent William Moore from executing his right to use an old right of way, but a decision was made in Moore’s favour by Judge McElligott. There had subsequently been a run in between the families while using the road, and the Moores took the matter to court, the Geaneys entering cross cases. During evidence, it was shown that a dispute had existed between the families since 1914. D J Browne, solicitor, appeared for the Moores and J M Murphy for the Geaneys (‘Reamore Case’ reported in Kerry News, 14 November 1930). [32] Death in Kerry: The Story behind The Field, RTE Radio 1 documentary by Ciaran Cassidy and Peter Woods. [33] Evening Herald, 2 November 1965.