‘A death-blow to the stage-Irish Tradition’

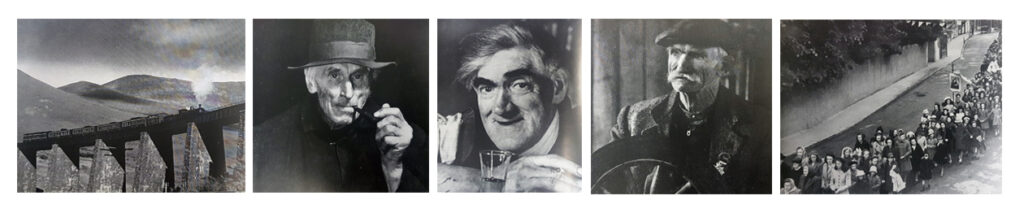

Adolf Morath, whose publications include Portrait of Ireland (1951) dedicated ‘to Irish Men and Women all over the world,’ was an acclaimed international photographer.[1] He visited Ireland in 1946 and 1947, and was in Killarney in 1948 professionally to photograph Kerry life, ‘leaving out the usual pig and caubeen.’

He was interviewed in that year about his ‘superb pictures’ and said there was ‘no limit’ to all the photographs that could be taken in Ireland for he had never seen ‘such variety of scenic beauty, such evidence of cultural and artistic activity, such a wealth of personalities packed into one small little country’ as he had in Ireland.[2]

He informed the interviewer that he was born in Cheshire (in another interview he said he hailed from Holywell, Wales) but his parents, who were jewellers and watchmakers, came from the Black Forest. He was intended to follow in this field but found the work irksome. He was twelve when he got his first box camera, and started in a coal-shed his father converted into a dark room in a Wallasey back garden. By sixteen he was a member of an amateur photographic association.

The interviewer described him as ‘a man of medium height, with a massive head, and a formidable chin’ who spoke with ‘a slight German accent and a boyish enthusiasm’:

When I came over here, I knew nobody, but one friend led to another friend, and then my friends grew like a snowball rolling along.[3]

Morath made friends easily and was particularly impressed with the hospitality extended to him. The county of Kerry appealed to him in particular, as he roved around with his three cameras and two lamps. The interviewer described his apparatus:

His equipment is of the simplest. He does not even use an exposure meter. From the highest in the land to the lowest, known spots and spots unknown – he wandered far off the beaten tourist track – his camera made a record of the Irish scene, and when his pictures are placed in book form, they should form one of the best pieces of propaganda for the country that has yet been contrived.

He described Adolf as ‘an artist who uses the camera for his brush’ who only photographed people and places that appealed to him. As Morath explained:

A person comes to have their portrait taken. They may not have the qualities you want. You might as well go to a poet and pay him to write a sonnet about you. It is the same thing.

Morath’s portraits were described as ‘distinctive in their lighting and texture’ giving ‘the impression of oil-paintings’:

His photographs, whether they are taken in a room of state or a country public house possess this common distinctive quality.

Morath explained that he got his lighting effects from the Old Masters, bringing the lessons of the older art to the new.[4]

Morath hoped to procure material in Ireland for a book, but quickly found he had enough for two books. He intended them for the American market because he held that people had ‘altogether the wrong view of Ireland.’ He hoped his images would ‘sell Ireland to the world. This type of book has not been done before about Ireland.’[5]

Morath, realising that Ireland had ‘something different to other countries,’ and impressed by the great number of ‘photogenic and unusual types,’ sought to get within the covers of a book ‘the whole life of Ireland from the first citizen, to the humble fisherfolk in the Blasket Islands.’[6] Portrait of Ireland was the result, published in 1951, in which he ‘captured the elusive spirit of Ireland.’[7]

Morath presented a signed copy to Eamon de Valera:

Adolph Morath, a tall, bulky figure, wearing a wide-brimmed black hat, walked into Government Buildings today with a book under his arm. He moved with the air of an artist and all the easy grace of a king of ‘freelance’ photographers for that is what he is. Once inside the building he was immediately escorted to the Taoiseach’s apartments where he presented Mr de Valera with his book which contains 173 photographic illustrations, a pictorial representation of life in Ireland from the President, down to the humblest toiler. On the cover is a representation of the Cross of Cong, inside the cover Mr Morath has written: To An Taoiseach, Mr de Valera, with all good wishes to you and the Irish Republic. If this book, even in a small measure, contributes to a better and more universal understanding of the cultural life of Ireland, I shall feel that, as an admirer of this country, I have performed a worthwhile task.[8]

Morath is credited with being the first photographer to capture the Dail in session since the foundation of the State, part of a project to photograph parliaments of the world in session for a publishing firm.[9]

He was commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Irish Government to photograph important literary people one of whom was the camera-shy George Bernard Shaw, who wrote:

Give Morath my address and send me his. We must get into direct communication. I will give him a sitting. He is first rate. I have never seen better photographs.[10]

Morath’s range is shown in Portrait of Ireland, wherein he writes:

As soon as I set foot on Irish soil the whole atmosphere gripped me; I felt I had arrived in an entirely different world … In this book I introduce a number of personalities, some of them famous, some unknown but all of them typical of the men and women of Ireland.[11]

Among the 171 black and white images appear buildings, portraits, men and women at work, children and scenic shots. Kerry images include Carhan, Daniel O’Connell’s birthplace; Ross Castle and Muckross Abbey, a Dingle fisherman, a Kerry farmer, a Killarney laneway, Mickey Moriarty of the Kenmare branch railway line, Aghadoe Castle, a Blasket Islander bringing home fuel. Portraits include the MacGillycuddy family who hailed from Tiernaboul and ‘Kruger’ Kavanagh of Dunquin. A wonderful portrait of Wicklow man, Captain Robert Monteith, who spent a period in hiding in Kerry in 1916, also features.

A considerable section devoted to Dublin includes buildings such as Charlemont House and city scenes showing the statue of Nelson’s Pillar, and people, for example, Robert Maire Smyllie, editor of the Irish Times, and the Earl of Iveagh, chairman of Guinness. Portraits of poets Seumas O’Sullivan, Daniel Kelleher, Austin Clarke and Patrick Kavanagh number among other artists including novelist Kate O’Brien, and composer Dr John Francis Larchet.

The unnamed include a porter in the Gresham Hotel, a newspaper salesman, a Dublin landlady, an announcer of Radio Eireann. The stage is represented by Ria Mooney, producer at the Abbey, actress Siobhan McKenna, playwright Lennox Robinson and the Earl of Longford, founder of the Gate Theatre. Artists include Evie Hone, stained-glass designer; Hilary Heron, worker in wood and stone, Sean O’Sullivan, RHA, portrait painter; Jack Butler Yeats, RHA, ‘one of the greatest of living painters’ and Sean Keating, RHA, Professor of Painting at the National College of Art.

The hierarchy finds place with Prime Minister Éamon de Valera, Senator Margaret Pearse (sister of William and Padraic); Maude Gonne MacBride and Sean MacBride; Chief Justice Conor Maguire, Deputy Prime Minister Sean Lemass and President Sean T O’Kelly.

Elsewhere the country is portrayed with assorted photographs: machine-won turf near Portarlington, Hugh McGoldrick, a Cavan farmer; a Cork alleyway and fruit market, a thatched cottage in Mayo, the harvest in Sligo, the Spanish Arch Galway, a peasant woman of Connemara, an Aran Island home, haymaking in Cavan, a Tipperary farmer’s boy, a Wicklow factory, a Donegal weaver, the penstock pipes of the Shannon hydro-electric scheme.

Morath’s photographs were widely distributed and published in many newspapers and periodicals including the Capuchin Annual and Vexilla Regis Maynooth Laymen’s Annual.

Industrial Photography

Morath, who was a fellow of the Royal Photographic Society (he exhibited colour transparencies there at the age of eighteen) and also a newspaper cameraman, developed his interest in industrial photography and was commissioned to photograph the British steel industry in the 1950s. Frederick Marquis, the 1st Earl of Woolton, regarded him at this period as ‘the most dramatic camera artist in the country.’

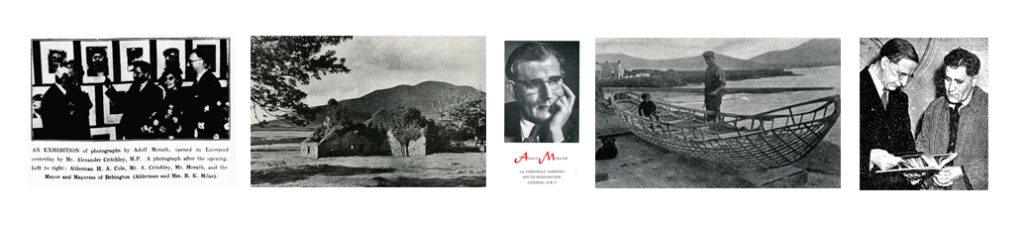

Morath travelled to Kuwait in 1956 commissioned by the Kuwait Oil Company. In 1957, he included some of those photographs in an exhibition about industry sponsored by the Manchester Guardian, whose editor, Alastair Hetherington – whose photograph, and that of London editor Gerard Fay Esq, as well as scenes from the print room, were included in the exhibition – paid tribute to his work:

Adolf Morath is an artist in colour. His photographs of people and industry – whether by the Persian Gulf or the Pentland Firth – are superbly composed. He has an exceptional eye for combining delicate gradations of tone and the subtler interplay of shades. Only, I think, in the best of American industrial photography – and it is rare – can his standards be equalled. Certainly I have seen nothing on this side of the Atlantic to rival his work.[12]

More than twelve of the titles exhibited were from his Kuwait commission, including an image of C A P Southwell Esq CBE, MC, Managing Director of Kuwait Oil Co Ltd; night scenes from Mina al Ahmadi, and a class in progress at Kuwait State School.

Other exhibits illustrate his client base: Sir Leonard Sinclair, Chairman and Managing Director, Esso Petroleum Co Ltd; Sir George (Horatio) Nelson, Bt, FCGI, MIMECHE MIEE, Chairman, English Electric Co Ltd; Supersonic Wind Tunnel at Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Ltd, Whitley, Coventry; Ford Consul on the Riviera courtesy Ford Motor Company Ltd; images courtesy Mufulira Copper Mines Ltd; images courtesy Roan Antelope Copper Mines Ltd; Her Excellency Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, High Commissioner for India, London; General Sir William Morgan, GCB DSO MC Hon LLD, The Chairman, Siemens Edison Swan Ltd; images courtesy British Iron & Steel Federation; Quentin Lumsden Esq, Public Relations Officer, British Iron & Steel Federation; tractor school courtesy of Massey-Harris-Ferguson, Coventry; factory at Bournville.

He travelled to Kuwait again in 1958 and 1960.[13] In 1961, he was sponsored by the Rhodesian Selection Trust Group of Companies to travel to Rhodesia.

Morath had a studio in London. Fieldings Travel Guide to Europe advised travellers looking for a photographer to go there and ‘try Adolf Morath, a genius with the lens’:

American business moguls, financiers, and public figures who go to England are making a beeline to him these days. He doesn’t like to make studies of women. He charges $147 a sitting and even so is a very busy man, so you’ll save time by making advance arrangements through his studios at 14 Cornwall Gardens, South Kensington, London SW7.[14]

Adolf Morath

Adolf Morath was born in Liscard, Wallasey, Cheshire on 3 June 1905, one of three children of Leopold Lawrence Morath and Adelheid (Adelaide) Sophia.[15] His father was of the firm of Morath Bros, clock and watch manufacturers, 71 Dale Street, Liverpool, established in the early nineteenth century.[16]

Leo Lawrence Morath of 14 Ennerdale Road, Wallasey, died on 15 February 1937.[17] On the day of his funeral, the premises of Morath Bros remained closed for the day as a sign of respect. In his will he left £11,898 to his widow.[18]

In the year following his father’s death, Adolf Morath gave an exhibition of photographic portraits at Bluecoat Chambers, Liverpool, which was opened by Alexander Critchley, MP:

Mr Morath shows over 160 vivid likenesses of personalities and types classified in ten sections beginning with Merseyside’s civic leaders and administrators, prominent public personages, consuls of a score of countries, members of the Playhouse Company, to well-known women of Liverpool and named and unnamed figures familiar in the streets and dockland.

Mr Critchley remarked that Morath had made ‘a distinct contribution to the art of the city.’[19]

Adolf’s siblings were Walter Herbert Morath, who died on 28 February 1977[20] and Marie Margaret Morath, who died on 27 March 1986. [21]

The place and date of death of Adolf Morath have not been discerned, though it may have occurred in 1977. The fate of his photographic collection is not known. We should be glad to hear from anyone who may be able to offer more detail.

Note

Andrew Sawdon, on social media, compliments the above article on the Morath family who originated from the Black Forest where clock-making developed from a home industry (a seasonal occupation in the farmhouses when there was less farm work and they were snowed indoors). He writes: ‘They were a clan, more or less related to one another, expanded into jewellery and came to Ireland where Adolf would have known close relatives, Morath and Beha (his mother’s family); businesses they founded are still around including Hilsers in Tralee.’

An account of Hilsers Jewellers was published in the Kerryman, 6 March 2003, ‘A New-look for a Tralee landmark as Hilsers Jewellers re-opens this week.’

____________________

[1] Copy held in IE CDH 95. Other publications include Faces before my Camera (1947) which has a strong focus on Liverpool and Wales, Children before my Camera (1948), Pets before my Camera (1949), which includes a photograph of the author on the dust jacket; Portrait of Shrewsbury School (1953) introduced by J M Peterson, Headmaster, whose portrait appears in the book; Animals in Camera (1963) (collaboration). The books contain technical information and instruction on his methodology. [2] Irish Independent, 27 September 1948. [3] Irish Independent, 27 September 1948. [4] Irish Independent, 27 September 1948. The interview continued: ‘Originally he intended to procure material for one book. Then he found himself with material for two. One volume will be devoted to people, the other to places. In the meanwhile he hopes to give an exhibition of his work in Dublin in the spring.’ [5] Irish Independent, 27 September 1948. ‘He said it in all modesty, and, having seen his work, I agree with him. Still there is a certain irony in a Britisher of German parents selling Ireland to the world.’ [6] Cork Examiner, 21 December 1951. ‘He had to widen the range somewhat to take in the religious life, museum treasures, landscapes and the life of the cities and towns, but this son of German parents who was born in Cheshire, had done his job with a thoroughness which is characteristic of his forbears.’ [7] Morath had a number of working titles for his Irish study, including Ireland I Saw. The National Archives in London holds correspondence between Morath and George Allen & Unwin Ltd (1949 and 1950) regarding his proposed publication. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/ac707c46-c757-40c4-bd40-250d05d8c870 [8] Cork Examiner, 21 December 1951. [9] Irish Examiner, 17 November 1949. He gained the permission of the Committee of Procedure and Privileges. ‘Last year [1950] he spent many a day taking shots of the House from all angles but these, we understand, were destined for the Department of External Affairs and do not appear in his present [1951] book.’ [10] Dust jacket, Portrait of Ireland (1951). [11] Introduction, Portrait of Ireland. He acknowledges Tom O’Gorman, the Public Relations Officer of the Irish Tourist Board; the Cultural Committee of the Ministry of External Affairs, Dublin; Messrs Guinness; the Irish Hospitals Trust; Aer Lingus; Trans-World Airlines; Rev Fr Senan of the Capuchin Annual and Timothy O’Sullivan, Director and Manager of the Gresham Hotel. [12] The catalogue, entitled ‘An exhibition by Adolf Morath Industry through my Colour Camera’ sponsored by the Manchester Guardian, January 1957, includes a photograph of Adolf Morath, and titles to 62 images shown at the exhibition. [13] Iridescent Kuwait: Petro-Modernity and Urban Visual Culture since the Mid-Twentieth Century (2021) by Laura Hindelang. [14] Fielding’s Travel Guide to Europe, later known as Fielding’s Europe, aimed at Americans travelling to Europe, was reprinted many times in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. Its author was Temple Hornaday Fielding (1913-1969), credited with being the founder of modern American travel guides, who began in 1948. The 1960 edition (13th) was dedicated to his brother, Captain Dodge Fielding, FA. This edition states the guide was first published in 1923. T H Fielding died from a heart attack at Palma, Majorca in May 1983 aged 69. Morath had a portrait studio in Liverpool before the Second World War. Morath’s Pictorial Press Agency was based at 44 Whitechapel, Liverpool and he later seems to have had studios at 62a Bold Street Liverpool c1936-1941, and was perhaps associated with the commercial photography firm Associated Photo Services, 44 Whitechapel, Liverpool. [15] The following notices are recorded here for genealogical purposes: Leopold Morath, Liverpool, was married on 6 October 1864 at Altglashutten Catholic Church, Grand Duchy of Baden, to Sophia Isele, of Neustadt, Baden (Liverpool Albion, 10 October 1864). A son was born on 24 June 1866 at 25 Tetlow Street, Liverpool, and another on 21 September 1868 at 25 Tetlow Street, Walton Road. Sophia Morath, wife of Mr Lawrence Morath, died at 71 Dale Street, Liverpool on 27 October 1868 aged 29. A son was born on 14 June 1875 at 71 Dale Street to the wife of Leopold Morath. [16] The company appears to have specialised in cuckoo clocks. ‘Morath Brothers, based at 71 Dale Street. Originally from the Black Forest area of Germany, part of the Morath family settled here and became renowned as importers and distributors, especially of the cuckoo clock’ (Liverpool Echo, 30 December 2004). The company announced its closure after 132 years trading in 1971 (Liverpool Echo, 21 June 1971). [17] Requiem Mass for Leo Lawrence Morath was held at SS Peter and Paul’s Church, interment took place at Rake Lane Cemetery, Wallasey. Adelaide Sophia Morath died on 20 July 1971. The following notices are worth recording here for genealogy: Lorenz Morath of Newstadt, Baden, died at 71 Dale Street, Liverpool on 20 November 1878 aged 50. Buried at Anfield Cemetery. Robert Leopold Morath renounced probate in the will of John Frederick Egner in 1902. Louis Emil Morath died suddenly at 49 Trafalgar Road, Wallasey, on 4 October 1938 in his 71st year. He was buried at Rake Lane Cemetery. Peter Morath (born c1937/8) of 43 Wood Lane, Greasby, Merseyside was described as a second cousin of Adolph Morath the photographer. He may have emigrated to New Zealand. [18] Liverpool Echo, 21 August 1937. [19] Liverpool Daily Post, 1 November 1938. [20] Walter Herbert Morath was buried in Rake Lane Cemetery, Wallasey. In the same grave Mary S Oberle died 5 July 1917 and Theresa Faller died 30 January 1961. [21] Marie Margaret Morath left a will proved in Liverpool District Probate Registry on 31 August 1988 in which Peter Dominic Hoskinson and Wolfgang Heun were named as executors.